From the Jonestown jungle massacre to the streets of Brixton, cults will always attract leaders and followers

With the latest Netflix documentary series shining a light on the murky world of cults, David Barnett meets the man who has devoted the last 40 years to fighting these shadowy organisations which ruin lives

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In November 1978, Ian Haworth – along with the rest of the world – watched in horror as footage emerged from Guyana where more than 900 people died in a move of “revolutionary suicide” orchestrated by cult leader Reverend Jim Jones.

Unlike many appalled at the mass deaths that saw bodies piled up around the remote settlement dubbed “Jonestown”, Haworth was thinking: “That could have been me.”

Just a month previously, he had emerged from the clutches of a cult in Canada, and his experiences, his escape and the pictures of Jonestown prompted him to devote the next four decades to investigating, campaigning against and plucking people from the hold of cults.

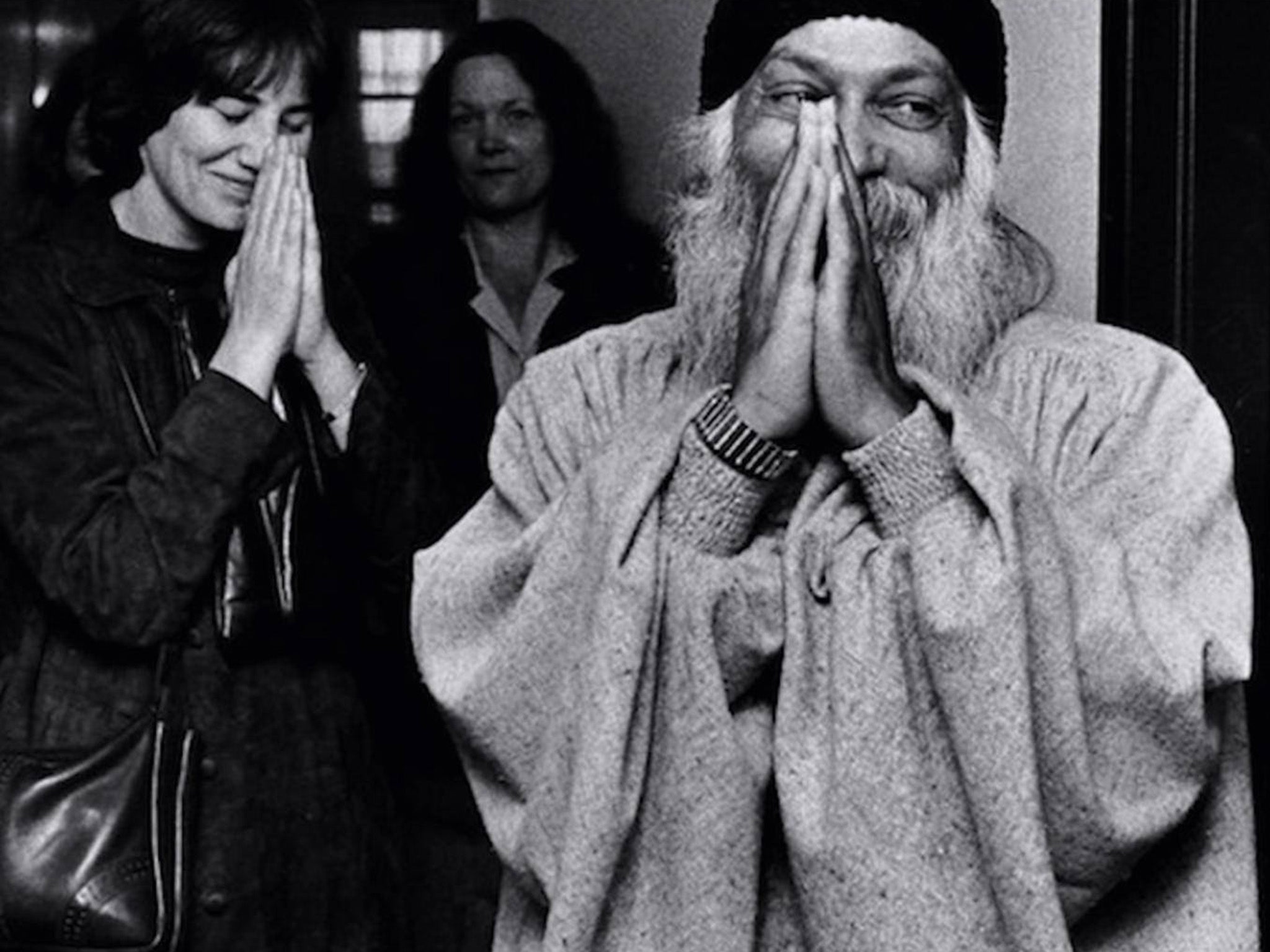

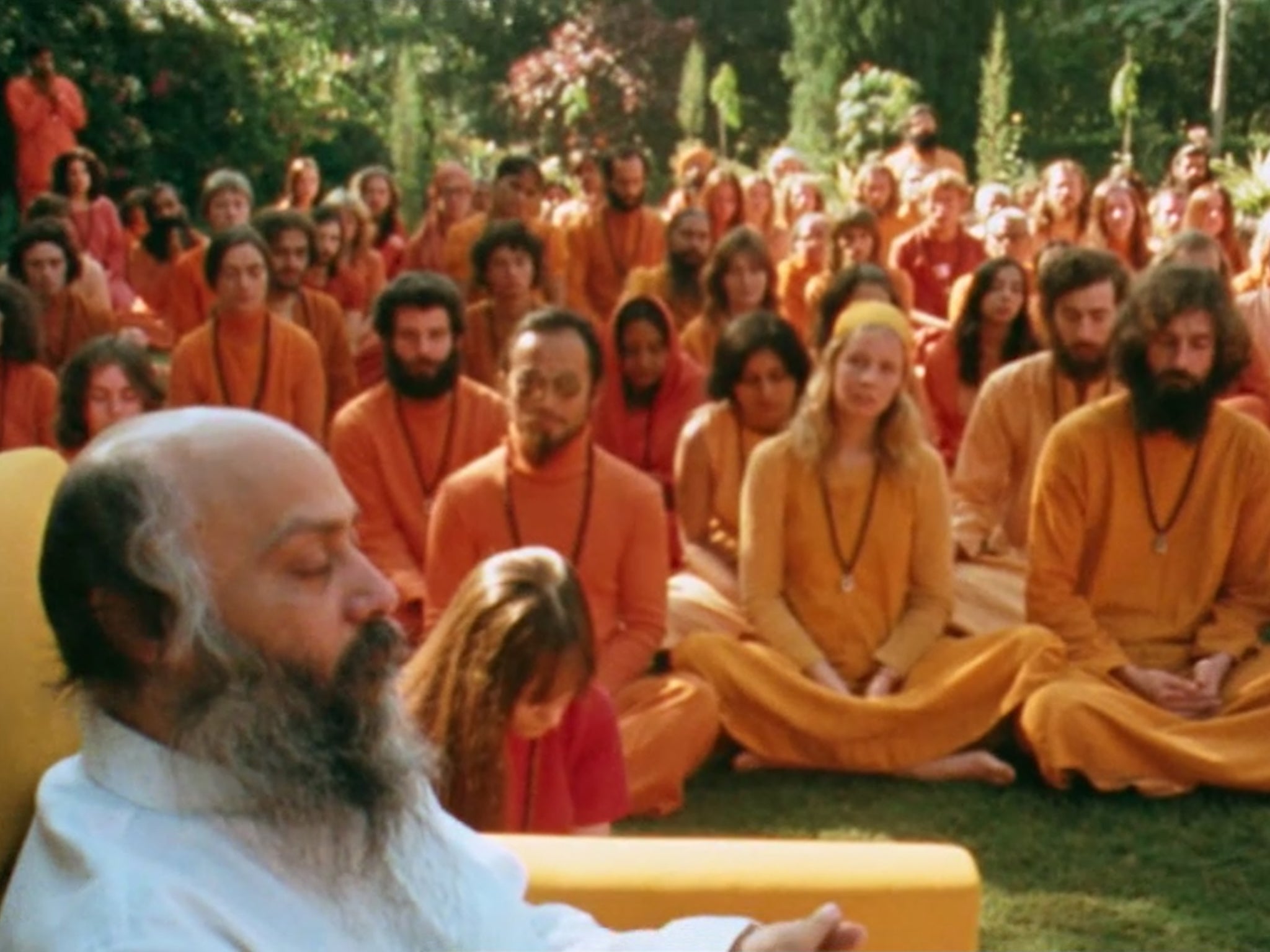

Cults are very much back in the public eye at the moment, due in no small part to the documentary series Wild Wild Country, which debuted on Netflix in March. The series follows Indian guru Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, also known as Osho, and the free-love community which built up around him in Oregon in the 1980s.

It’s perhaps the archetypal image of the cult we’ve come to recognise: the followers of Rajneesh, who died in 1990, dressed in orange; their leader was a charismatic Indian guru (who relocated to the US after the Indian government frowned upon his activities); the disciples gave huge amounts of cash to their figurehead, lost contact with their families.

But cults don’t have to follow the pattern of Rajneeshpuram, as the Oregon ranch was renamed, or the bloodbaths at Jonestown or Waco, where David Koresh’s sect the Branch Davidians was raided by the FBI in 1993. More often than not, they are more mundane than that… but no less damaging.

Katy Morgan-Davies last month published a book about her experiences living in Brixton with the cult leader – and her father – Aravindan Balakrishnan, who was jailed on charges of rape and imprisonment in 2015. Morgan-Davies managed to flee the cult in 2013 after 30 years – her entire life.

Cults are back in the news again, but for Ian Haworth they never went away. As the head of the UK-based Cult Information Centre, he spends his life collating information on cults, offering advice and help to those who have escaped – or wish to – and campaigns for stricter legislation to control the reach and influence of these malign groups.

“I’ve dealt with more than 1,000 different cults,” says Haworth. “That includes the Rajneesh group. The Netflix documentary series has generated a lot of interest internationally, which can’t be a bad thing.”

That interest comes in peaks and troughs, naturally, with particular focus at the moment thanks to Wild Wild Country and Morgan-Davies’ memoir. Haworth says: “I suppose the biggest peak we’ve had began on 1 January 1999, when there was a huge amount of cult activity related to the millennium, when all kinds of things were promised or predicted. Of course, mathematically, the millennium ended at the end of the year 2000, not the end of 1999, but cult leaders don’t really care about such things. They care about money, and controlling people, and power.”

Born in Lancashire, the son of a farmer, Haworth emigrated to Canada in 1972 while in his twenties. By 1978 he was working as a communications consultant for a large company, and had never given a thought to cults. Aged 31, he happened to be stopped by a woman with a clipboard in a Toronto street.

“She was very attractive and I was very single,” remembers Haworth. “When she asked me if I had time to answer a few questions for what I thought was market research, I said yes.”

But after only half a dozen questions, the tone of the exchange altered. The woman told Haworth that his answers indicated he’d fit in very well with a group she was involved with, and that it would enable him to give something back to society rather than just taking. A meeting was taking place the following week and Haworth was invited along.

“I turned up and there were about a hundred people there,” he says. “A woman was talking about her addiction to alcohol and drugs, and how this group had helped her. I was planning to sneak away at the end, because I’d been brought up to be polite and didn’t want to just walk out. Then they brought out drinks and cakes, and as I’d paid $2 (£1.50) to attend I decided I might as well get my money’s worth before leaving.”

During a break he went into the corridor for a cigarette, and that’s when the cult members pounced. Haworth had seen his doctor not long before and been told if he carried on smoking like he did he’d be lucky to see 40. The group told him that they would absolutely guarantee he would stop smoking if he attended a further course for $220. He’d already looked into smoking-cessation courses that were of comparable cost, so decided he’d give this one a go.

“The course took place in September, 1978,” says Haworth. “By the end of the course I’d given notice at my job, promised to dedicate my life to the cult, and handed over all my savings, which amounted to about $1,500.”

Even now, Haworth cannot identify the tipping point that turned him from someone who’d turned up for a meeting at the behest of an attractive woman to someone who gave himself, body and soul, to a cult, other than mid-way through the course when he stopped smoking. “I suppose that was the moment I went over to them – they had done what they said they would do.”

Cults often thrive on feeding into people’s desires. Sometimes they will promise success, artistic or creative talent, fulfil a desire in their targets to effect social change or, as with Haworth, to “give something back” to the world. They will promise freedom from addictions or improved physical or mental health. They’re what Haworth calls therapy cults, as opposed to the religious cults that offer more spiritual promises.

If you’re born into a cult you don’t have that ‘Real Ian’ vs ‘Cult Ian’ internal battle that I had. You emerge from that and the first question is… who am I? It’s an incredibly difficult and delicate situation

Over the next month, Haworth tried to recruit his friends and even neighbours to the group. They were appalled at the change in him, but, he says, “I thought they were wrong, I knew they weren’t part of the elite, like I was.”

It was an almost textbook recruitment, and Haworth firmly believes he would have been lost to everyone who knew him but for one error on the part of the cult. “Most cults programme their members against the media very early on. These people didn’t do that,” he says. And that was what saved him.

A neighbour gave him a copy of the Toronto Star which had featured a front-page exposé of the group Haworth was involved in, written by the investigative reporter Sidney Katz. Haworth read the piece and contacted Katz immediately to verify his facts. He then, as he describes it, “fell apart at the seams”. Having seen Katz’s research and evidence first hand, at the invitation of the journalist, Haworth angrily confronted the cult’s leaders, and they effectively banished him. He was finally free of them.

“That was in October,” he says. “Then, in the November, everything came out about the Jonestown cult. And I knew that could have been me. It took me 11 months to fully recover and get back to myself.”

It took that long for the nagging whispers of “Cult Ian”, as Haworth describes the person he was when he was with the group, to be finally silenced, and for “Real Ian” to reassert himself. And good sense would dictate that was the point he turned his back on cults forever and got on with his life.

“I come from a farming background in Lancashire,” says Haworth. “People used to say, ‘If there’s summat up, then tha’ does summat about it’. So I did summat about it.”

Sidney Katz put Haworth in touch with a TV producer called Peter Scott and together they set up what was first called the Council for Mind Abuse, and which later metamorphosed into the Cult Information Centre in 1987, now run as a charity.

I’ve dealt with more than 1,000 different cults. That includes the Rajneesh group. The Netflix documentary series has generated a lot of interest internationally, which can’t be a bad thing

Haworth and Scott concentrated on the group he had been involved with, even handing out flyers to a party of new recruits flown into Canada, exhorting them to go back to the airport. Faced with Haworth’s evidence, many of them did. Eventually, the resistance proved too much for the group. “Toronto wasn’t big enough for the both of us,” he smiles. “They got out.”

Haworth doesn’t know where they are now, or if they still exist. Cults change their names often, to keep one step ahead of the media or inquisitive minds, and to muddy the paper trail they leave behind. Besides, he soon had more than enough on his plate as more and more people began to get in touch, especially after he had relocated back to the UK.

One of the Cult Information Centre’s primary roles is working with ex-cult members. He likens the trauma that recovering cult followers go through to PTSD, and says systems to deal with and help them are variable, if present at all.

He would also like to see stronger laws to deal with cults; there’s no specific legislation surrounding them, and it’s only when cult leaders are discovered to have committed actual crimes, such as Aravindan Balakrishnan in 2015, that the law can act.

The Aravindan Balakrishnan case, and the revelations of Katy Morgan-Davies in her new book, add an extra dimension to Haworth’s work. It’s one thing to try to help cult members who have managed to break free return to their old, pre-cult lives, but what of those born into cults?

“If you’re born into a cult you don’t have that ‘Real Ian’ vs ‘Cult Ian’ internal battle that I had,” says Haworth. “You emerge from that and the first question is… who am I? It’s an incredibly difficult and delicate situation.”

And don’t think it is only stupid people who would fall for a cult. Experts say that cults are most likely to be attractive to intelligent, well-educated people… they have flexible minds; can consider and be seduced by the alternative lifestyles offered by cults.

From Jonestown in the Seventies to Rajneeshpuram in the 1980s to Brixton in the 2000s: cults endure, and spring up all across the world. Nothing about modern life and its complexities has inured us against the attractions of a charismatic guru or cult leader.

“They start off wanting the usual things,” says Haworth. “Money, sex, power over people. Then, after perhaps about 10 years, they start to believe the things they say, they maybe start to believe they are gods.”

And as long as the false gods continue to prey on the innocent, Ian Haworth will continue his 40-years-and-counting battle against the scourge of the cults.

For more information on Haworth’s work at the Cult Information Centre go to cultinformation.org.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments