‘I can’t be afraid of the risk to privacy right now’: Coronavirus and tracking app surveillance

As the disease spreads, so does the use of tracking apps. But is our privacy a fair price to pay to fight the virus? Kareem Fahim, Min Joo Kim, and Steve Hendrix investigate

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A smartphone app in Turkey asked for Murat Bur’s identity number, his father’s name and information about his relatives. Did he have any underlying health conditions, the app wondered, presenting him a list of options. How was he feeling at the moment, it asked. It also requested permission to track his movements.

None of this felt intrusive to Bur, a 38-year old personal trainer. The app, which he had voluntarily downloaded, had helpfully warned him that his neighbourhood was a coronavirus hot spot. “There are people in our country still having parties and picnics. I do not see the harm in people being followed,” he says. “There is an extraordinary situation in the world.”

To the feelings of fear, restlessness, insecurity and sorrow taking hold around the globe, the pandemic era has added another certainty: being watched.

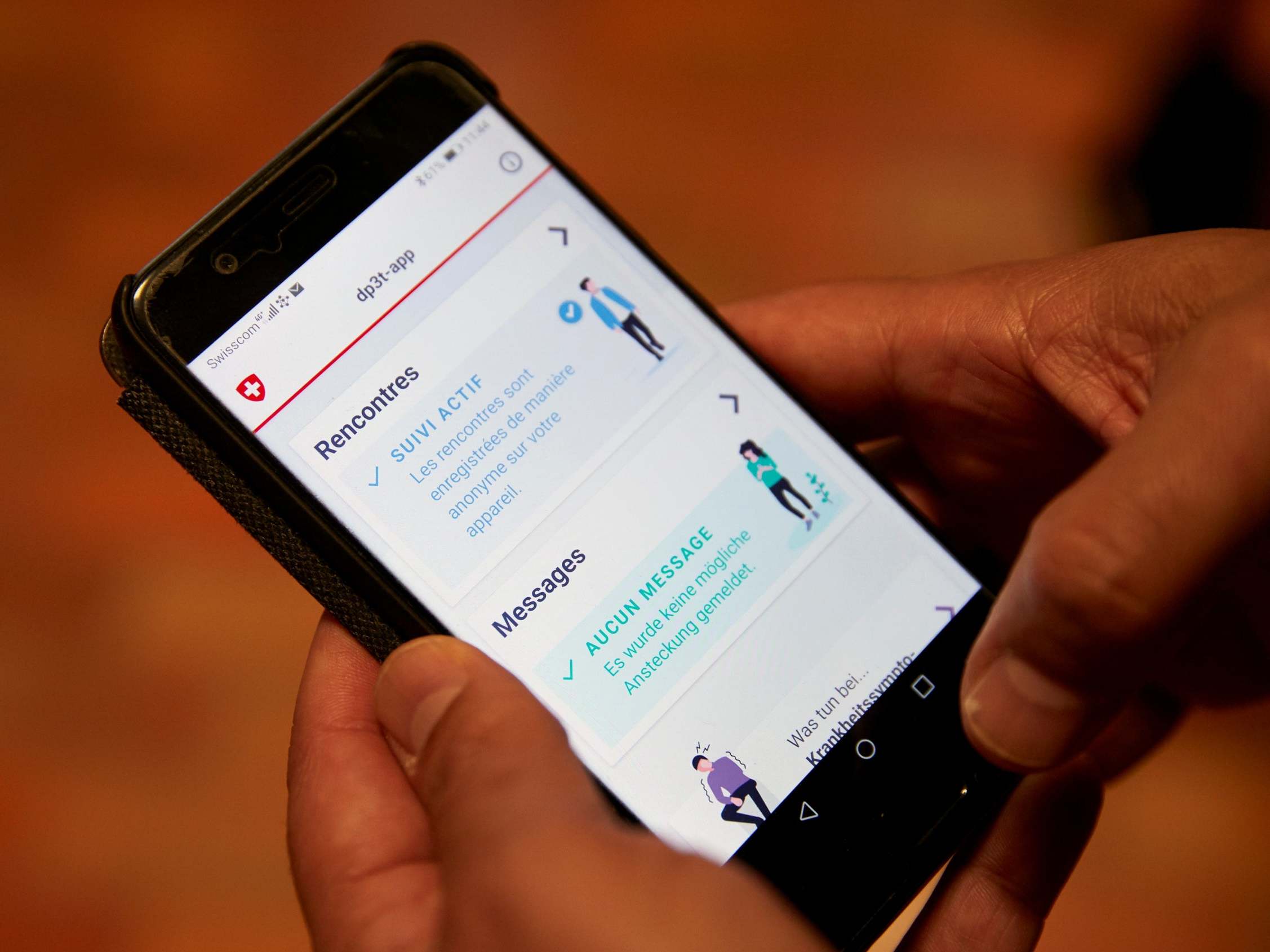

In a matter of months, tens of millions of people in dozens of countries have been placed under surveillance. Governments, private companies and researchers observe the health, habits and movements of citizens, often without their consent. It is a massive effort, aimed at enforcing quarantine rules or tracing the spread of the coronavirus, that has sprung up pell-mell in country after country.

“This is a Manhattan Project-level problem, that is being addressed by people all over the place,” says John Scott-Railton, a senior researcher at Citizen Lab, a research centre at the University of Toronto.

He is among a group of researchers and privacy advocates who say there is not enough debate over the consequences and utility of the new surveillance tools, and no indication how long the scrutiny will last – even as the flood of prying apps are becoming a reality for millions of people, like solitude and face masks.

Because of the pandemic, surveillance is a “necessary evil,” says Lee Yoon-young, a South Korean university student who was under strict, government-monitored quarantine after returning home from her studies overseas. “I am not disturbed since I understand that stronger quarantine control allows those not under stay-at-home order to continue on with their lives without a nationwide lockdown,” she says.

At least 27 countries are using data from cellphone companies to track the movements of citizens, according to Edin Omanovic, the advocacy director for Privacy International, which is keeping a record of surveillance programmes. At least 30 countries have developed smartphone apps for the public to download, he says.

The monitoring has raised fewer objections in countries that have been more successful at battling the virus, like Singapore, and provoked a much louder debate in Europe and the United States – a difference that is reflected in the numbers of people who voluntarily download tracking applications.

In South Korea, millions of people have signed up to use websites or apps that show how the virus is spreading. More than 2 million Australians quickly downloaded a coronavirus contact-tracing app that was released on Sunday. But 3 in 5 Americans say they are unwilling or unable to use an infection-alert system being developed by Google and Apple, a Washington Post-University of Maryland poll has found.

People are anxious. They are worried. They want to go back to normal, to handle doorknobs, to online date

Epidemiologists and government health officials have taken a central role in designing some of the coronavirus tracking programs. Privacy groups have been far more concerned when intelligence agencies have taken the lead, as they have in Pakistan and Israel, or when governments outsource tracing to private companies.

Infection-tracking software by NSO, an Israeli company, has attracted criticism before it has even launched. The company is best know for designing surveillance tools used by authoritarian governments to spy on dissidents, journalists and others. A person close to NSO says its new coronavirus tracking software, called Fleming, was being tested by more than two dozen governments around the world.

The pandemic has all but silenced the debate about encroachments on privacy by corporations, Scott-Railton says. “People are anxious. They are worried. They want to go back to normal, to handle doorknobs, to online date.

“We are looking to anyone who is pitching hope.”

Turkey, which is wrestling with one of the worst outbreaks in the world, uses technology to track the spread of the virus in at least two ways. One is the app, called Life Fits in the Home, which solicits personal details to track infections and provides information, including the location of nearby hospitals and pharmacies.

The government has said that it is doing mandatory tracking of people 65 years or older, who are required to quarantine, and sending them cellphone messages when they venture out of their homes.

I have no doubt that Turkey will use such apps as a vehicle for pressure and surveillance when need be

There has been little public backlash against the surveillance in Turkey, where people are accustomed to an intrusive and increasingly authoritarian central government. Any misgivings have also been tempered by a feeling the state should be taking stronger measures to control the outbreak.

Cigdem Sahin, an economics professor at Istanbul University, says she didn’t think twice before downloading the tracking app, even though she is normally wary of government surveillance.

“I actually think it might be useful to surveil the spread of corona – if the system is used effectively and does not give an error,” she says.

“I have no doubt that Turkey will use such apps as a vehicle for pressure and surveillance when need be,” Sahin says.

But her primary concern was whether the app could work properly. It told her little she did not already know about her neighbourhood, called Fatih, where there was a high concentration of infections. So she stopped using the app.

“We are being watched and our lives are being recorded, and one wonders how to deal with it,” she says. “There is no escaping it.”

One of the most critical questions is whether the programs actually yield reliable information about infection chains. Hasan Kasap, 73, a retired university professor, says he received a text message from the health ministry last month warning him to stay home, though he says he had not left his apartment in weeks.

“This approach made me lose my trust in this institution or this tracking system and even made me feel insulted,” he says. “Location information is private. It should remain private.” After the message, he turned off the option on his own phone that allowed it to be tracked, he says.

The Korean travel data can be accessed not just by health-conscious residents but also voyeuristic onlookers, which was ‘concerning’

South Korea has never imposed a nationwide lockdown or travel restrictions in response to the coronavirus, only issuing strong advisories against nonessential travel as part of a national social distancing campaign. The country’s coronavirus response, featuring widespread testing for infections, is often held up as a model around the world.

As part of that effort, South Korea’s health authorities track the movement of people and then later retraces the steps of those diagnosed with the virus by using GPS phone tracking, credit card records, surveillance video and interviews with patients. The patient travel histories are published without names to help others identify whether they crossed paths with a virus carrier.

Another smartphone app monitors thousands of people under self-quarantine and reports their movements to the government.

Lee Yoon-young, the university student who has been under the remotely monitored quarantine, says she welcomed the geopositioning app on her phone that allowed the government to pinpoint her location.

Lee returned to South Korea after her studies in the United Kingdom were disrupted by the pandemic. The contrast between the government response in the two countries was stark. In Brighton, where she studied, she had relied on patchy news reports to identify virus-prone locations to avoid. In South Korea, she has found it reassuring to be able to see online travel histories of virus carriers.

But the Korean travel data can be accessed not just by health-conscious residents but also voyeuristic onlookers, which was “concerning,” she says, adding that personal information about infected people should be redacted.

Singapore also mobilised early to contain the epidemic by aggressively tracking chains of infection, imposing harsh penalties on patients who violated quarantine rules and mounting ubiquitous public awareness campaigns – while avoiding a full lockdown. Cellphone apps were developed to helped enforce self-quarantine rules and aid the contact-tracing effort by making use of Bluetooth technology.

I would have fought for my personal liberties on many levels before. Now I am the one trying to restrict the people around me. I am more of a scold

Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan, an author and journalist who lives in New York, saw how strictly quarantine rules were enforced when she flew to Singapore in late March and was forced to self-isolate in a hotel. Her location was monitored through her cellphone and twice a day, she was required to verify her whereabouts for the government, occasionally by sending a picture of her surroundings. Once, she got a video call from health officials, just to make sure she was where she said she was.

“They were very strict about it,” she says. “As they should be.”

Her experience in New York, with one of the world’s deadliest outbreaks, made her more willing to accept government monitoring and less tolerant of people flouting quarantine and other distancing rules. “These are desperate times. I would have fought for my personal liberties on many levels before. Now I am the one trying to restrict the people around me. I am more of a scold,” she says.

The intrusions were easier to accept because Singapore’s government appeared to have citizens’ welfare in mind, and no “ulterior motives”, she says. But the number of intrusions was rising: one government app allowed people to report violations by their neighbours. More recently, some grocery stores had required people to provide their identity numbers to enter.

“It’s worrying once you give up these liberties,” she says. “Is this the way it’s always going to be?”

The experience of countries hurriedly deploying apps and similar surveillance software highlights the limits of such technology and the challenge of widescale public buy-in even in places that are largely open to being watched.

Experts warn, for example, that apps relying on Bluetooth radios can provide inexact location data and falsely identify people as infected.

Jason Bay, the director of Singapore’s contact tracing app, called TraceTogether, said in an online post last month, “If you ask me whether any Bluetooth contact tracing system deployed or under development, anywhere in the world, is ready to replace manual contact tracing, I will without qualification say that the answer is no.”

John Scott-Railton of Citizen Lab says the effectiveness of such apps was ultimately determined by “human social behaviour and racial and age demographics”.

Surveillance violates the constitutional right to privacy and there exist other tools to deal with the coronavirus

Apps are of limited utility unless a large percentage of a country’s population downloads them, and even then, the reach of the software is limited to people who own smartphones, which often excluded lower income people, racial minorities and people over 65, he says.

Some surveillance initiatives have also run into organised efforts to rein them in.

In Israel, a group of civil liberties groups went to court in March to block a far-reaching effort by Israel’s internal security agency, the Shin Bet, to track cellphones of Covid-19 patients. The agency uses cellphone location signals of known coronavirus cases and its own vast trove of data to detect users who have been in proximity to an infected person – information health officials use to alert people to self-isolate.

A fortnight ago, the Israeli Supreme Court ruled that the government tracking would require parliamentary legislation to continue much past the end of April, when the emergency measure was due to expire.

Adalah, the Legal Centre for Arab Minority Rights in Israel, was one of the groups that filed a petition with the high court objecting to the government’s reliance on emergency powers to expand the reach of its security apparatus. “Surveillance violates the constitutional right to privacy and there exist other tools to deal with the coronavirus,” says Suhad Bishara, a lawyer for Adalah.

While contact tracing is an important tool for isolating infected people, “extending the work of such an agency to do civil-related matters becomes very problematic,” she says, adding that many Palestinians, subject to surveillance or interrogations by Israeli security services over decades, fear the agency would misuse health records and other data it has access to.

Roxanne Halper, 60, who works in international development and leans towards the left end of Israel’s political spectrum, says she would normally be wary of government surveillance, but not this time.

“I feel like I should have a problem with it and yet I don’t,” Halper says during a phone interview from her home on a small kibbutz between Jerusalem and Tel Aviv.

Like many, she says health considerations now seem more pressing than privacy. She had even downloaded a voluntary government app and appreciated it every day when it told her she had had no contact with a known coronavirus case. (The app is separate from the Internal Security Agency’s tracking efforts.)

“I take comfort from that,” she says. “I can’t be afraid of the [risk to privacy] right now. I’m much more afraid of corona and what it’s doing to society.”

Kim reported from Seoul and Hendrix from Jerusalem. Shibani Mahtani in Hong Kong, Zeynep Karatas in Istanbul and Brian Murphy in Washington contributed to this report.

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments