Is coral gardening the front line in the fight against climate change?

After witnessing a barren reef on her first scuba dive, Sarah Frias-Torres came up with a unique way to bring these underwater ghost towns back to life. The ‘Mother of Corals’ speaks to Andy Martin about why restoring our climate must begin under the sea

At the age of six, before she could even swim properly, Dr Sarah Frias-Torres learnt to snorkel in the warm waters around Barcelona. She actually liked sinking. Ten years later, she took up scuba diving. It was on such a dive that something happened that would change her life forever. No, she was not attacked by a giant squid or a shark. Quite the opposite: “I discovered that the Mediterranean was empty.”

This was her initiation into eco-collapse. She was witnessing first-hand the impact of the anthropocene on coral reefs. The adventurous teenager, hooked on Jacques Cousteau, realised that we are killing corals. I know exactly how she feels. Surfers and corals both love reefs. For many years, while honing my surfing skills, I spent a lot of time bumping around on the ocean floor. “I was just checking out the reef,” was my usual refrain. In the end I decided to cut my losses and head straight down more voluntarily. If you want to see climate change in action you only have to put on a mask and duck your head under the water (preferably warm) and have a good look.

“Bleaching”, which is another word for coral dying, is pervasive. I’ve been lucky enough to see some insanely beautiful coral reefs, but my personal response, when I see one that is dying or dead, is to swim away as fast as possible, vowing hazily to do something (but what exactly?) about climate change.

Fortunately Frias-Torres did not run away. She came up with a solution. She is saving old reefs and giving birth to new ones, and has become known as “Mother of Corals”. Frias-Torres begat corals. She is (to my mind) Aquawoman.

Having studied biology at the University of Barcelona, she went on to specialise in marine conservation at the School of Ocean Sciences at Bangor in north Wales. The temperature of the water on the Welsh coast came as a bit of a shock and persuaded her to invest in a very thick wetsuit. She went on to work in Florida, at the Nasa Space Centre (where she was a Fulbright scholar), studying the ocean around Cape Canaveral while the astronauts were looking up at the stars. “The fact is,” she says, “we know less about the bottom of the ocean than we do about the surface of the moon.”

Now 40-something, based in Seattle, where she is coral reef conservation and restoration specialist at Vulcan Inc, she is a citizen of the underwater world. Her first major insight was that the sea urchin population in the Mediterranean was being depleted due to overfishing.

More usefully, Frias-Torres went on to demonstrate that marine reserves really do work when the rules are properly enforced and people don’t go sneaking in and scoffing every living creature, spiny or otherwise. In other words, it is possible for fish populations to recover. Could something similar, she wondered, be done for coral reefs?

Coral reefs are the London, New York and Beijing of the underwater world, bustling population centres, host to the ichthyo multitudes. “They cover around 1 per cent of the ocean floor,” Frias-Torres points out, “but they provide a habitat for up to 25 per cent of marine life.” I’ve seen turtles, dolphins, rays, sponges, nudibranchs, and sea cucumbers all hanging out down there, and so many fantastic, rainbow-coloured fish weaving in and out of corals, I can’t begin to name them all, but they include one with what may be the longest name of any fish, the humuhumunukunukuapua’a (or “humuhumu” for short). It boasts the title of “state fish” of Hawaii.

The Great Barrier Reef off Queensland is roughly 20,000 years old. Atolls (such as in the south Pacific) take 30 million years to form. Some coral reefs have been around for as long as 50 million years. But in the 20th century they started to come undone. Like the rainforest or any decent ecosystem, they are fragile. They flourish only in a narrow band of water temperature and depth (the so-called “photic zone”, which gets enough sunlight). The first reefs to degrade, hit by a perfect storm of pollution and overfishing and coral diseases, were the reefs around Florida and the Caribbean in the 1970s and 1980s. “They were like the canary in the coalmine,” says Frias-Torres. “They were dying sooner there than anywhere else.”

When a coral goes into decline, the fish abandon it and all you can see is water. No more humuhumu, no more madding crowd, no more marine rainbow. Having had a grandstand view of a few deceased corals, I had assumed that all coral reefs around the world were, in a word, doomed. It was just a question of when. How long could they hold out for? Not long, I assumed.

As Melissa McCarthy points out in her wonderful under/over water book, Sharks, Death, Surfers: An Illustrated Companion, the obituary is the natural genre for our encounters with the deep. From Noah and Jonah through to Moby Dick and Jaws, we are fixated on “death by water writing”. The apocalyptic mentality kicks in all too readily. But to Frias-Torres’s way of thinking, it’s too soon to kiss goodbye to coral. It’s not a cemetery down there yet. Not quite.

“I could see that the situation of coral reefs was getting worse all the time.” But Frias-Torres had the simple conviction that what could get worse could also get better, with the right help. Reefs could be turned around, the damage reversed. Conservation by itself – trying to put a stop to or at least reduce fishing and habitat destruction – wasn’t enough. Too passive. So Frias-Torres launched her own personal and very practical Extinction Rebellion. She thought in terms of eco-restoration. “Whether it’s a forest or a wetlands or a reef, you can jumpstart a system that has degraded.”

She started by leading a coral restoration programme in the Seychelles, in the Indian Ocean, from 2013 to 2016. When she dived down for the first time she realised that there were sections of the reef that were still flourishing. “The reef is so full of life. You can actually hear it, even with goggles on, underwater. There is an energy. Fish are going about biting things, nibbling. The whole reef is alive. That was overwhelming.” But, in contrast, there were other sections that were completely bleached and desolate. “It was like the moon, or a ghost town. The silence was deafening. That was scary to me, I thought: what have we done?”

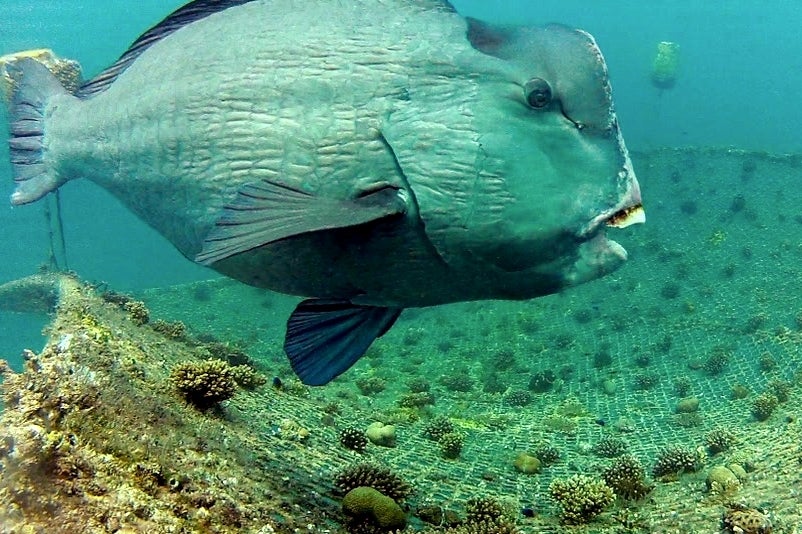

The question is: what can be done to bring the reef back to life? The answer: coral gardening. It’s like ordinary gardening, but under water. With her international team, she has managed to grow some 40,000 corals, each one the size of a football, and then cement them (or tie them) to the reef to create a coral nursery, a coral maternity ward.

And the great thing was, “The fish came back.” It was like a resurrection. The ghost town was bustling again. “It was completely empty of life, it was dead,” says Frias-Torres, like someone who has witnessed (or, in fact, conjured up) a miracle, “and now it’s alive again.”

Male, female, hermaphrodite, LGBT+: corals tick all possible boxes. Breeding can be sexual or asexual, depending on their mood. They don’t necessarily need to mingle and are capable of solitary self-reproduction. The “polyps” that get the whole party started are asexual. Each polyp is an upside-down jellyfish. The primal polyp attaches itself to a rock on the sea floor, sticks out a few tentacles to collect passing plankton, and then proceeds to clone itself. The structure of a coral reef is essentially colonial. One colony joins forces with another and over a long period of time they become a reef, a coral empire. Algae and fish come and live there. When it works, it’s a riot of colour and endeavour.

If the polyps are not performing, Frias-Torres has been known to collect coral sperm and eggs and speed up procreation. Inevitably, there are difficulties associated with being a coral gardener. Every now and then you get hit by a hurricane, or a passing tsunami. With the best will in the world, you can only realistically work underwater for half the year. But Frias-Torres shows that, even with limited resources, coral restoration is feasible. In the midst of a general mood of pessimism about climate change, she has come to a surprising conclusion: “We can fix things.”

Now she had the necessary know-how, but she wanted to expand, “to have more impact, to make more change, globally”. Which, oddly enough, was exactly the mission of Vulcan Inc, the brainchild of the late Microsoft co-founder Paul G Allen. They do various good things, such as fighting piracy and illegal fishing, and protecting sharks (and other land-based species). But the specific objective of the Allen Atlas, launched in October 2018, and overseen by Lauren Kickham, is to map the entire world’s shallow coral reefs. Frias-Torres says: “It’s obvious that we can’t fix all the reefs until we know where they are. We know what to do, but we need to know where we’re going. Where to place the nurseries.”

It’s a work in progress, focused at the moment on six main reef systems (including Hawaii and the Great Barrier Reef), but the aim is to have mapped the entire planet by 2020. Coral cartography relies partly on satellite data, partly local knowledge, combined with a degree of AI wizardry to create the mosaic. You can take any number of pictures from space, but they can only tell you a limited amount about what is going on at reef level. You can find the amazingly high-resolution maps online (Allencoralatlas.org).

Right now, somewhere in the world, Frias-Torres is trying her best to make corals more “heat resilient” by bringing in and planting polyps from other parts of the ocean that can handle higher temperatures. Saving the corals is saving the planet. And therefore us too (even if we spend most of our time eating or burning or bleaching it). We are apt to forget that most of our oxygen – around 70 per cent – comes from the oceans. It’s not just trees. Phytoplankton, the tiny plants the live beneath the surface of the water and drift along with ocean currents, capture carbon dioxide and produce oxygen as a byproduct of photosynthesis. If we kill off the corals we’re all going to need scuba diving equipment above water too.

Frias-Torres also has another project with a view to holding back climate change: to sequester more CO2 by regenerating wetlands, mangrove forests and marshlands. The UN recently declared 2021-2030 to be the decade of “ecosystem restoration”. She is in the vanguard of the fightback. She also has good advice for young women wanting to go into science. In a phrase that encapsulates her life, she quotes Bruce Lee: “Be water, my friend.”

Andy Martin is the author of ‘Reacher Said Nothing: Lee Child and the Making of Make Me’. He teaches at the University of Cambridge

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments