'He was happy. So far as I knew': A family reels after an 11-year-old’s suicide

Rylan Hagan was a model sixth-grader who had just qualified for a trip to Disney. Why did he kill himself?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.After 11-year-old Rylan Thai Hagan hanged himself with a belt from his bunk bed three days before Thanksgiving, people wanted to know why he did it. He was a model sixth-grader at Perry Street Prep School in north-east Washington, where he received a stipend to tutor other students. He was a basketball player whose team had just qualified for a tournament at Walt Disney World. He played the trumpet.

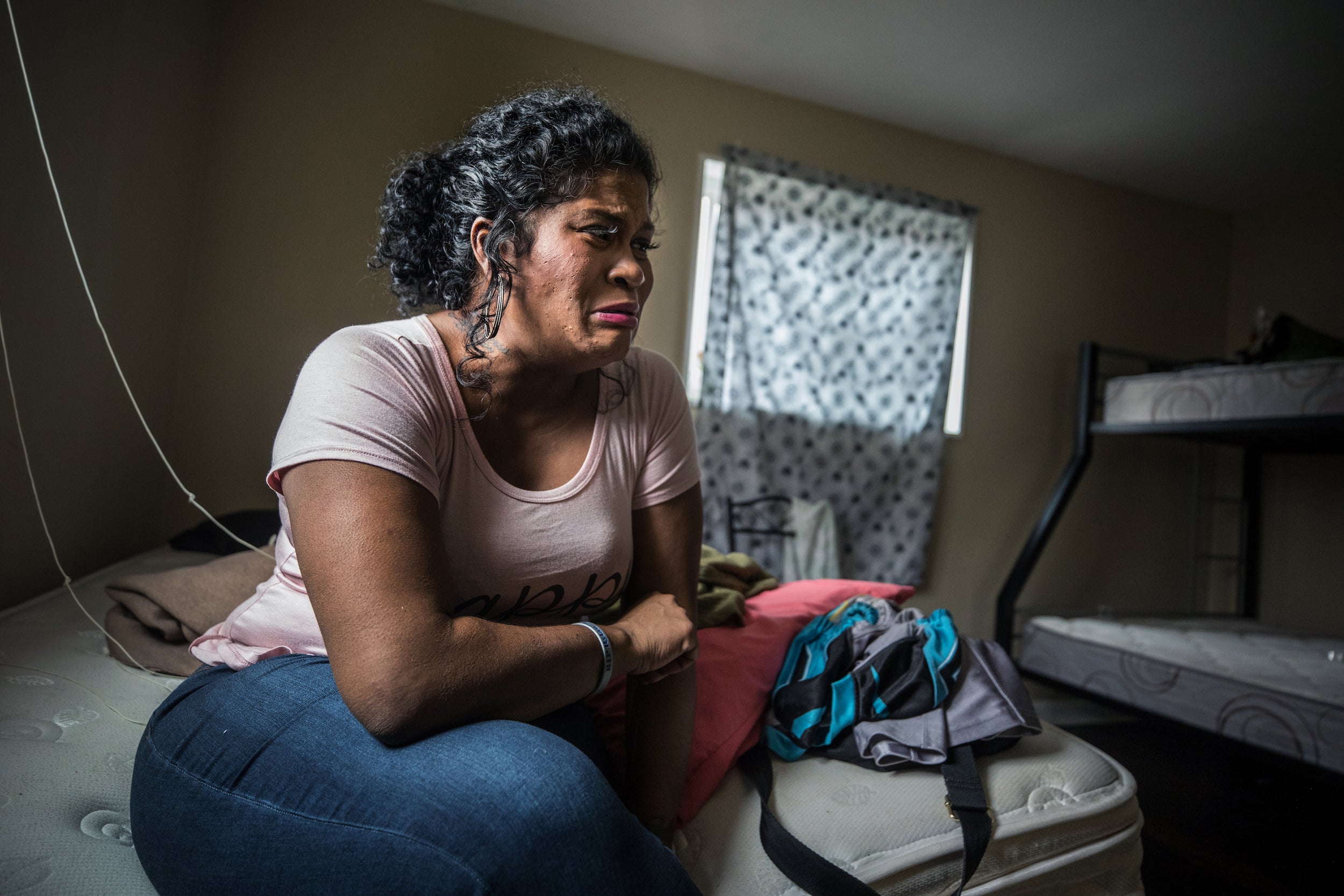

Standing in the room where her only child had taken his life less than two months earlier, that question tortures Nataya Chambers. The apartment, where she has not slept since his death, is in disarray, belongings spilling out of boxes as she prepares to search for a new start.

“He was the perfect son,” she says. “Very smart. He was happy. So far as I knew.”

Rylan appears to be the youngest person to take his own life in Washington since at least 2013 – though data for last year isn’t available – and the idea that a child so young would commit suicide is unfathomable to most. But in January this year, another African American child, 12-year-old Stormiyah Denson-Jackson, apparently hanged herself in the dormitory of her charter school in south-east Washington.

In a city that records a pre-teen suicide about every other year, two such deaths weeks apart were particularly jarring.

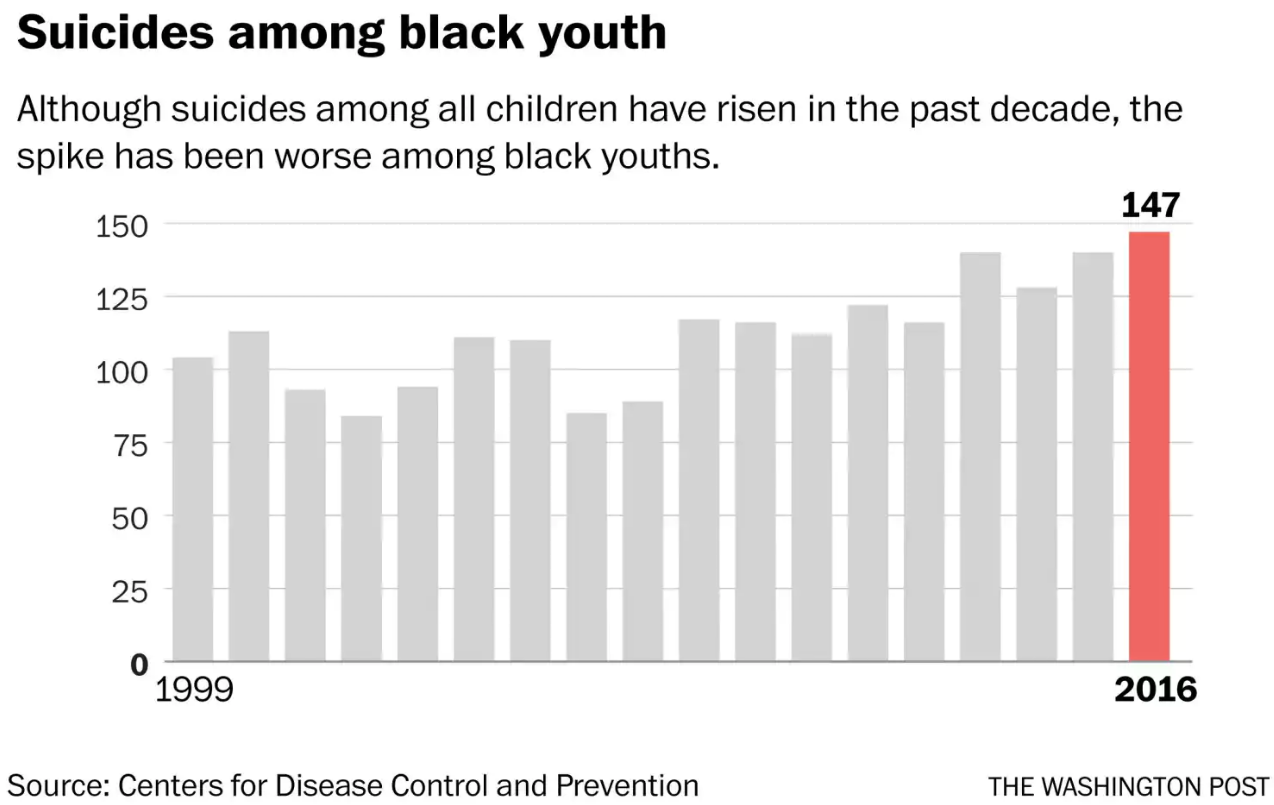

Nationwide, suicides among black children under 18 are up 71 per cent in the past decade, rising from 86 in 2006 to 147 in 2016, the latest year such data is available from the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. In that same period, the suicide rate among all children also increased, up 64 per cent.

Researchers aren’t sure what has fuelled the slightly larger rise for black children. Some speculate that those affected by racism might be at greater risk. Another factor could be the notion that suicide isn’t a problem in the black community, hindering prevention efforts.

Among the youngest children, suicide for those 13 and under rose 114 per cent from 2006 to 2016. In a bright spot for black youth, the rate of growth in this age group rose more slowly, at 30 per cent.

Chambers was on the phone with her son on 20 November not long before he ended his life. She was getting a Thanksgiving donation basket at the Salvation Army when Rylan told her he was frustrated with a malfunctioning printer at their boxlike, one-bedroom apartment where they shared a room.

When she called his phone again, he didn’t answer. When she entered the apartment, she called his name, and he didn’t answer. She looked in the bathroom – he wasn’t there. Then she went into the bedroom.

She tried loosening the belt – first with her hands, then with her teeth. She ran into the kitchen, got a knife and cut him down.

Her neighbour, Cerrina McArthur, heard the screams and ran into the bedroom. Rylan was lying on his back, eyes closed, hands purple, foam around his mouth. She started CPR and kept at it until the ambulance arrived.

“I didn’t know he was gone,” McArthur says.

A police report says little, indicating officers responded about 1.40pm to the apartment. “Chambers returned to the listed location and found Rylan in an unconscious state, inside the bedroom,” the report states. “He was transported to a hospital where he was pronounced.”

Police took Rylan’s laptop and phone – anything that might reveal why he took his life. He hadn’t left a note. Their investigation is ongoing, and the medical examiner hasn’t released results of an autopsy.

Without official information, Rylan’s family, friends, coaches and teachers looked for answers. They were hard to find.

Chambers wondered about the music her son listened to, such as rapper XXXTentacion, who posted a video to his Instagram account last year that appeared to show him hanging himself. Her son also played video games, interacting with other players online. Was he bullied in some way she’d overlooked?

She once asked him to do chores, and he reacted emotionally, unreasonably, saying he wanted to kill himself. Was this just acting out, or a real warning sign? Her mother, Rylan’s grandmother, had struggled with depression. Was it hereditary?

“With children, it’s hard to tell,” Chambers says. “They smile, they don’t tell you what’s wrong, and they go back to being a child again.”

Rheeda Walker, a psychology professor at the University of Houston, says her research into African American mental health shows possible links between perceived racism and suicide among black youths. And the perception that suicide isn’t a black problem makes it difficult for parents, teachers and others to spot warning signs.

“If there is a belief that black children do not kill themselves, there’s no reason to use tools to talk about suicide prevention,” she says.

Rylan’s home life wasn’t without challenges. His parents had a turbulent relationship and criminal records they were trying to put behind them.

They were together on and off, and tell different stories about when and why they broke up. In 2016, his mother, an exotic dancer-turned-caterer who had pleaded guilty to sexual solicitation five years earlier, was living with Rylan in a shelter for about a month. They then moved to the subsidised unit.

“It was a starter kit to help us get going in the world,” Chambers says of the apartment.

The starter kit appeared to be working, as Rylan seemed unaffected by his stint in the shelter, his mother says.

Ronald Hagan, his father, was active in his son’s upbringing. Before Rylan’s birth, he served 10 years in prison for selling drugs, he says, and tried to steer Rylan towards a better path.

“My personal life didn’t affect him,” he says. “I knew, through all the mistakes I’ve made in my life, I wanted something better for him. In his life – daily, at the school, in sports – I wanted to make him better than me. That’s why I didn’t name him a junior.”

When Hagan was homeless during the winter of 2016, he was with Rylan each day, picking him up from his mother’s house to take him to school, then picking him up after tutoring to take him to football or basketball practice.

“I never seen the trigger – he was with me all the time,” Hagan says. “In school, he always put a smile on other kids’ faces.”

Angie Pearson, whose 12-year-old son, CJ, was a close friend of Rylan, says Rylan often stayed at her house on weekends when she had a place in north-east Washington. In 2016, when Rylan’s mother and father were homeless, he stayed with her for two months, she says.

“We was like a safety spot,” Pearson says. “I knew he was happy, being with us. I wished he could be with me forever.”

Standing with his mother outside his school, CJ says he was three when he met Rylan. Although Rylan was a year younger, they became inseparable. They played football in the same league. They “made their own fantasies”, CJ says, pretending they were superheroes. CJ’s favourite was the Flash; Rylan’s was Deadpool.

After CJ’s family began staying in a shelter on the campus of the former General Hospital, he saw Rylan less often. “In my head, I kept thinking it was partly my fault,” CJ says of Rylan’s suicide. “I thought it had to do with me not seeing him any more.”

CJ isn’t sure why Rylan did it. Once, Rylan asked CJ what suicide was, and CJ told him. They watched a video online of people jumping off a bridge.

“I told him to stop – don’t look at it no more,” CJ says. “We promised that we would never try it or attempt it. He agreed, until recently.”

Niyesha Coleman, who taught Rylan in fourth and fifth grades at Perry Street, said he was consistently on the honour roll and was trusted to help other students in the computer lab. He sometimes called her “mom”.

“I loved him like my own child,” she says. “Anybody you talk to has nothing but great things to say about this kid.”

Sports were a big part of Rylan’s life, his father says. He’d started out unable to catch a football – Hagan recalls throwing him 100 passes until he picked up the skill. A week before his death, Rylan travelled to North Carolina and won a regional basketball championship, qualifying for a trip to Orlando, Florida, that he never took.

Hagan wants to start a foundation – one that focuses on the mental health of young people. He tried to reach out to Stormiyah’s family after the girl apparently hanged herself at Seed Public Charter School last month.

Patricia Denson-Jackson, Stormiyah’s mother, declined to comment on her daughter’s death, and autopsy results are pending. Media reports indicate her parents complained she was bullied at the school. The Washington Post doesn’t usually report on suicides, but Stormiyah’s death was widely covered in local media because of where it occurred. Rylan’s family discussed his death to promote suicide awareness.

At Stormiyah’s wake in January, the 12-year-old lies dressed in white as hundreds line up to pay tribute. They circle in front of the casket, linger a few moments, then walk away with tears in their eyes.

Mourners say she was a model student and a gifted dancer and singer. Vincent Gray of the DC Council says he will designate Stormiyah an honorary member. Some express scepticism that she had taken her own life, wearing “Justice 4 Stormy” T-shirts.

“I pray that we continue to surround this family with love,” says the Rev Christopher L Nichols.

National Institute of Mental Health director Joshua Gordon explains some of the latest research surrounding suicide rates in the US.

Jeffrey Bridge, director of the Centre for Suicide Prevention and Research at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, says parents shouldn’t dismiss signs that a child might need help.

“Take it seriously,” he says. “Talk with a mental health professional. Definitely act on it. Talking to a child about suicide does not put the idea in their head.”

That’s a lesson that Tim Bryant, who coached Rylan in football and basketball, is grappling with. This was a boy he knew well – who was friends with his son and slept at his house many times. Rylan was a lefty, so Bryant taught him how to drive to the basket from the “wrong” side when everyone else on the court was driving from the right.

Whatever it was that led Rylan to take his life, Bryant didn’t see signs of trouble.

“It really opened up our eyes to pain,” he says. “Kids can be going through things ... what do you do? It’s not like you want to put it on their mind. As adults, we think about prevention by not bringing it up.”

That strategy isn’t endorsed by experts.

“Minorities often don’t seek treatment,” says Erlanger Turner, an assistant professor of psychology at the University of Houston who also studies race and culture. “What we know is that people at risk of suicide often suffer from some mood disorder or depression. If you’re not treated for these conditions, the risk is much higher.”

Preventing such a tragedy requires eternal vigilance, says Matt Brady, the Perry Street music teacher who taught Rylan to play the trumpet.

“You never know what one more hug, one more high-five, one more, ‘Hey, Rylan, are you okay?’ – what it could have done,” he says. “For me, I’m just trying to make sure I check in as much as possible.”

All that’s left are artefacts.

Trophies and medals. An urn with ashes inside. Rylan’s green bike, sitting in the apartment his mother abandoned after his death. A private Instagram account that can’t accept follow requests. Two funeral programmes – one created by his mother, one by his father – stuffed with photos.

Infant Rylan in a car seat. Rylan at a football game. Rylan eating ice cream. Rylan with a dog. Rylan underwater, swimming, wearing neon-green goggles.

“Rylan brought immense joy to everyone,” Hagan’s version of the programme says. “He was a treasure whose smile captured your heart the moment you laid eyes on him.”

McArthur, who tried to revive Rylan, says he sometimes comes to her in dreams.

“I feel his spirit,” she says. But he doesn’t say anything. “He just smiles.”

It’s time to move on. Rylan’s mother is cleaning the apartment, packing up for good.

“I had to finally come to grips and come home,” Chambers says. “I couldn’t stay here over the holidays. Some of this hasn’t been cleaned up since it happened.”

She already knows her next move: California, to open the catering business she planned before Rylan died. Like Rylan’s dad, she wants to start a foundation focused on young people’s mental health.

Weeks after her son’s death, she hasn’t yet bought her plane ticket but is sure of one thing.

“It’s gonna be a one-way,” she says.

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments