The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Did Charles Dickens invent Christmas? Bah, humbug, no he didn’t

As ‘A Christmas Carol’ reaches its 175th anniversary, the author’s great-great-great granddaughter tells Adam Lusher that the story was a call for compassion in the depths of near-unbridled capitalism – one that remains painfully relevant to this day

It was a land that had forgotten the season of good will. In 1843, in Britain, the iron hearts of the Industrial Revolution had no time for such fripperies as Christmas. This was an age of near-unbridled capitalism, where, officially, it was acceptable for nine-year-olds to work nine-hour days, and, unofficially, inspection was so lax you could get away with making them labour for much longer. Government departments had cut their Christmas “holiday” from a week in 1797 to a single day in the 1840s.

In St James’s, members of the Carlton Club, then a key component of the Tory Party’s organisational machinery, had a few years earlier thought nothing of arranging a committee meeting on December 25 itself.

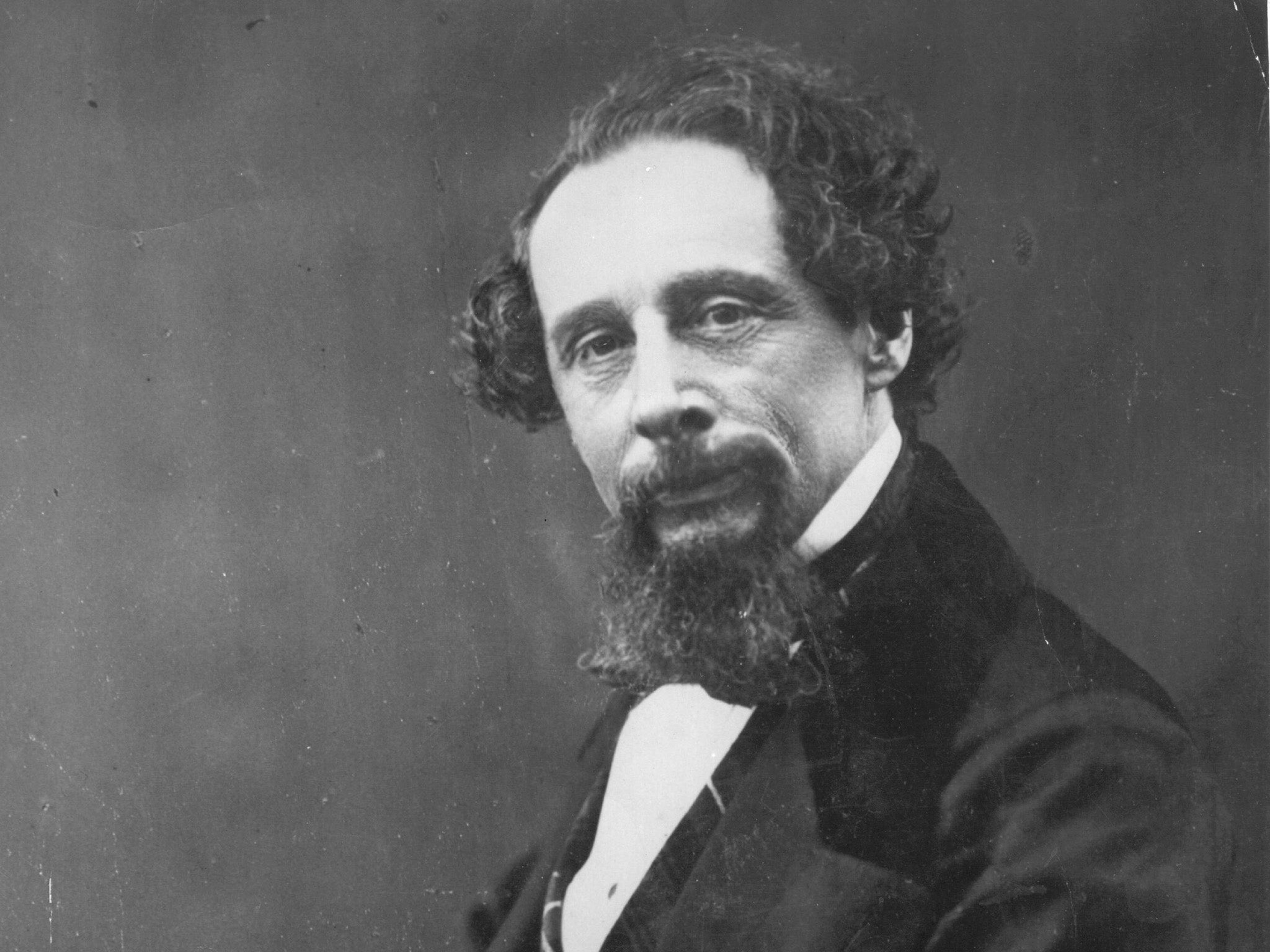

But in a rather grand house near Regent’s Park, a 31-year-old writer was about to change everything. Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol was an instant sensation when it was published, 175 years ago this week, on 19 December 1843.

The Illustrated London News declared: “Honour to genius! Charles Dickens, thou hast earned true glory! May the torch of Christmas … again impart good tidings to the poor man’s heart.”

The Scottish philosopher Thomas Carlyle was so affected by “visions of Scrooge” that he was, his wife noted, “seized with a perfect convulsion of hospitality and insisted on improvising two dinner parties”.

Author William Makepeace Thackeray, Dickens’ friendly literary rival, had to concede: “Had the book appeared a fortnight earlier, all the prize cattle would have been gobbled up in pure love and friendship, Epping denuded of sausages, and not a turkey left in Norfolk.”

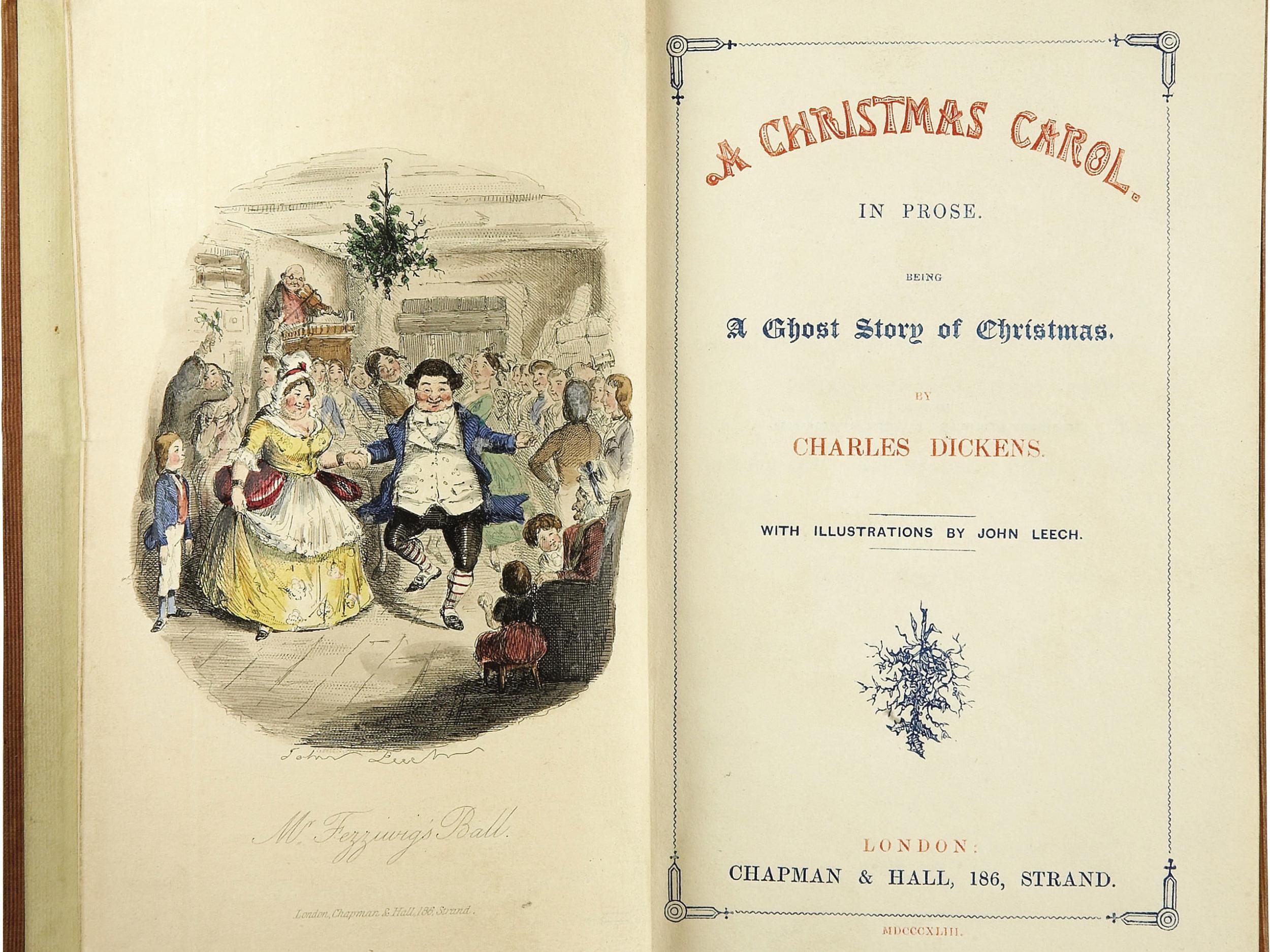

The publisher Chapman and Hall had to order a hasty reprint, because by Christmas Eve, with “orders coming in fast from town and country” it was clear the initial run of 6,000 copies had been way too small. And thus did Charles Dickens become the man who invented Christmas as we know it today. The great Dickens scholar FG Kitton said so in an essay in 1903, and the great Downton Abbey actor Dan Stevens proved it to be true by starring in the 2017 film The Man Who Invented Christmas.

And yet, bah, humbug and damn those pesky experts: lots of them disagree. Indeed, no less an authority than the US university-based Dickens Project now advises: “It is the smart thing to say that Dickens was the man who “invented” Christmas. Show you are smarter by disputing it.”

It is a view endorsed even by Dickens’ own great-great-great granddaughter, Lucinda Hawksley, the author of Dickens and Christmas. “He didn’t invent Christmas,” she says. “He captured what was already happening.” The new smart thing, it seems, is to argue that the initial death of Christmas was greatly exaggerated.

It is true that industrialisation meant fewer people were exposed to the rural squirearchy’s habit of opening their doors to the lower orders and staging grand Christmas celebrations – of the kind seen at Crewe Hall in Cheshire, where Dickens’ grandfather had been the butler, or in the pages of A Christmas Carol, where The Ghost of Christmas Past reminds Scrooge of how much he had enjoyed the dances organised by old Fezziwig.

But in 1843, outside the ranks of the aristocracy and aspirant upper middle-class imitators, Christmas was alive and well. Previous attempts to kill it had, after all, foundered on the stubborn resistance of “Merrie England”.

Puritan MPs may have ordered December 25 to be kept as a fast day in 1644, to avoid giving “liberty to carnal and sensual delights”. And Oliver Cromwell may be famous as the man who banned Christmas. But the “rude multitude” broke the head of the major who tried to enforce the “Ordinance for abolishing holy-days” in Canterbury in 1647, and by 1656 MPs meeting in parliament, on Christmas Day, were reduced to wailing: “The people keep up these superstitious observances to your face … We are returning to Popery.”

Other Victorian sources seem to bear out Ms Hawksley’s suggestion that Dickens was writing what he saw when he had the Ghost of Christmas Present show Scrooge “cheerfulness abroad … poulterers’ shops still half open, and the fruiterers’ radiant in their glory … hung-up mistletoe … pears and apples clustered high in blooming pyramids.”

And if there were inventors of Christmas customs around in the mid-19th century, you could argue that Dickens was not foremost among them. In her book, Hawksley describes how while Dickens was busy writing A Christmas Carol in 1843, the civil servant Henry Cole was busy inventing the Christmas card. Cole, later to become the first director of the Victoria and Albert Museum, did not have the time to write long letters to all whom he wished to contact over the festive period.

He hit upon the idea of writing a short card instead, and for the artwork he commissioned the quintessentially Victorian artist John Callcot Horsley: a man of great talent, known to more waggish elements as “Clothes Horsley” on account of his campaign against the male students of the Royal Academy being allowed to set eyes upon naked female models during their drawing classes.

Horsley produced a suitably decorous image of the Cole family, clothed, behind a banner reading: “A Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year to you.”

But when it came to Christmas being a time for family, few could surpass the example of the young royal family. It was while promoting such family values that Prince Albert also imported the Christmas tree tradition from his native Germany. In 1848 The Illustrated London News showed him with Queen Victoria and their children around a beautifully decorated tree. Suddenly it wasn’t just a select group of aristocrats who wanted a Christmas tree in their living room.

The year before, inspired, or so the marketing men claimed, by the crackle of a warm fire, London confectioner Tom Smith invented his first Christmas cracker in 1847 (although it took him until the 1860s to get the bang mechanism right). Dickens, meanwhile, could not be accused of inventing excessive wrapping, but it could be claimed he suffered because of it.

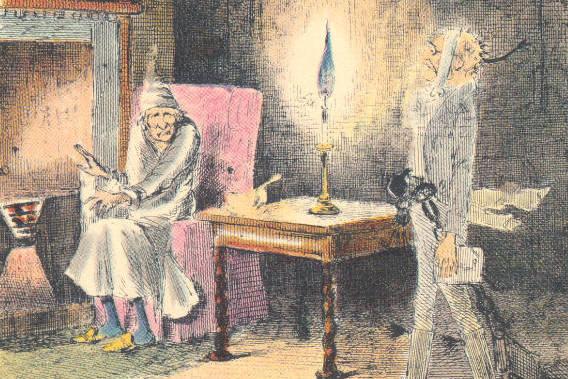

His insistence on paying out of his own pocket for lavish presentation – gold embossed cover, hand-coloured illustrations by John Leech – meant that when A Christmas Carol subsequently sold out, its huge production costs left Dickens with just £230 rather than the £1,000 he had been expecting. And if the Ghost of Christmas Present as described by Dickens and drawn by Leech bore a passing resemblance to Father Christmas, he was very much a work in progress, clad in Pagan green, his beard brown, not white.

It was the German American illustrator Thomas Nast who, in the 1860s, inspired by Clement Clarke Moore’s poem The Night Before Christmas and the elves of Bavarian folklore, did the most to give Santa red clothes, a white beard and a North Pole workshop.

What Dickens did do, though, was give Christmas one heck of a PR push. “He was showing what was going on,” says Ms Hawksley, “And making it even more so. After A Christmas Carol, people become obsessed with celebrating Christmas.

“Before, there were people who were, like Scrooge’s nephew, doing their own family Christmases, but after, suddenly everyone is thinking: ‘We should be doing that. Why haven’t we got people coming round and playing blind man’s buff?’

“It all starts to get much bigger.”

Newspapers began to notice the establishment of “plum pudding clubs” to help less well-heeled Victorians meet the cost of their Christmas dinner, so they too, like the Cratchit family, could hear “the pudding singing in the copper”. Other clubs helped them buy a goose, maybe even a “prize turkey” as big as the boy asked to fetch it by the reformed Scrooge.

And, says Ms Hawksley, fewer employers wanted to look like the unreformed Scrooge: “It became fashionable for people to expect that they could have time off at Christmas.”

Nor did Dickens stop at A Christmas Carol. He wrote four more Christmas books. Then in 1850 he brought out the first “Christmas Number” of his newly created magazine Household Words, working with other writers to pack it with stories for the consumption of “the teeming millions”, as Reverend JH Morgan called the intended readership of the two-penny weekly.

He became, as the Morning Chronicle put it, “the chief literary master of the ceremonies for Christmas”.

“When he died [in 1870],” says Ms Hawksley, “a Covent Garden barrow girl is supposed to have asked, ‘Mr. Dickens dead? Then will Father Christmas die, too?’"

But, Ms Hawksley emphasises, when he started it all with A Christmas Carol, Dickens had been seeking to do far more than simply become a sidekick to Father Christmas. “It was done as a protest,” says Ms Hawksley. “Christmas Carol was written from the heart, from Dickens feeling a desperate need to create change.”

These were the “hungry Forties”, a decade when Britain was in the grip of economic depression, when harvests failed and food prices were rising beyond the reach of many on low incomes. In May 1843 Dickens had railed against the wealthy attendees of a City of London charity dinner, calling them “sleek, slobbering, bow-paunched, overfed, apoplectic, snorting cattle”. They offered a stark contrast to the poverty he was encountering with ever greater frequency on his customary long walks through London.

Then in October Dickens was invited to give a fundraising speech at the Athenaeum in Manchester. This was the same Manchester where Friedrich Engels was beavering away at what would be published as The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844. Engels sought to shame the Victorian manufacturing class by documenting the “the misery and grime which form the complement of their wealth”.

He told of workers living in overcrowded slums complete with “foul pools of stagnant urine and excrement”, forced by “barbarous” employers to “work 30 to 40 hours at a stretch”, with child factory hands dying or being reduced to “a crowd of cripples” before they could reach adulthood.

Dickens walked some of the same streets and was horrified. At first, he considered producing a pamphlet on child poverty. Then he realised he could write something that would strike “a sledgehammer blow [with] twenty thousand times the force” of a mere pamphlet.

He wrote A Christmas Carol in just six weeks. “He saw galloping poverty,” explains Ms Hawksley, “And a government doing nothing about it. He couldn’t let it continue. He was desperate to do something.”

Into the mouth of Scrooge, Dickens inserted what, in his Manchester speech, he had called the “cruel absurdities” of the age. To the charitable gentleman seeking alms for the poor, Scrooge offers only a reference to the treadmill of the workhouse, which was about the only official social security option then available.

When the gentleman suggests the poor would rather die than enter the workhouse, Scrooge answers: “If they would rather die, they had better do it, and decrease the surplus population.”

The remark comes to haunt Scrooge once the ghosts start arriving, but it wasn’t far off what many thought about the poor being an unconscionable drain on the finite resources of a population that could not keep expanding forever. In most of his books, Dickens wanted to shame his readers into doing something,” says Ms Hawksley. “What he wants people to realise is that every single person is, like Scrooge, responsible for the poor they are ignoring.

“The point about Scrooge’s conversion is not that he buys the most expensive turkey. It’s that the turkey will feed a family.

“For Dickens, it’s not about diamonds, or going out and buying a load of plastic crap like people do at Christmas today. It’s about the fact that buying decent food and giving Bob Cratchit a salary increase will save Tiny Tim from dying.”

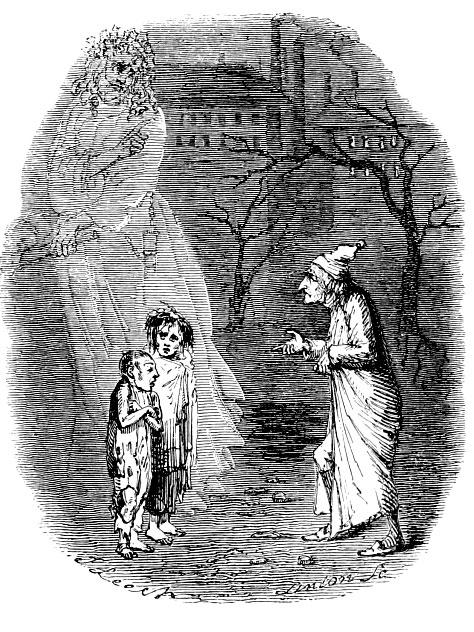

Nowhere, says Ms Hawksley, is the central message of A Christmas Carol more clearly stated than when the Ghost of Christmas Present shows Scrooge two emaciated children, a boy named Ignorance and a girl called Want. “Beware of them both,” the spirit tells Scrooge – and the reader. “But most of all beware this boy, for on his brow I see that written which is Doom, unless the writing be erased.”

“Dickens was saying,” explains Ms Hawksley, “that if you let Ignorance and Want grow up like that, they will become the Bill Sykes, the cruel and violent adults, of the future.

“Ignorance and Want are, in Dickens’ mind, about the most important characters in the book, the whole message, the whole point of it.”

“It really frustrates me,” she adds, “When they are missing from some [stage and film] adaptations, because that’s the heart of A Christmas Carol.”

What frustrates her more, however, is that 175 years after Dickens wrote A Christmas Carol, Britain remains blighted by the kind of poverty he was hoping to eradicate.

“Dickens was writing about this in 1843,” she says. “How in 2018 can we have the UN rapporteur on extreme poverty talking about child poverty in the UK? How can there be so many homeless people on the streets of London?

“How can I be hearing news stories that Christmas 2018 will be a so-called “bumper year” for the numbers of children suffering in cold houses because people can’t afford to heat their homes? There is absolutely no excuse for it when today we have so much more in terms of money, housing and knowledge of sanitation.”

In the 19th century, after “crying his eyes out” over A Christmas Carol, the author Robert Louis Stevenson, wrote enviously: “Oh, what a jolly thing it is for a man to have written books like these and just filled people’s hearts with pity.”

In the 21st century, Dickens' great-great-great granddaughter is grimly ambivalent about how the work continues to generate similar reactions. “Every year,” says Ms Hawksley, “I meet people who have read A Christmas Carol for the first time, who say, ‘I can’t believe how good it is, how it still resonates.’

“That’s wonderful in terms of Dickens’ writing, but depressing in terms of society. It frustrates me that A Christmas Carol is still so deeply relevant. It bothers me that 175 years after Dickens was writing about the children Ignorance and Want, we still have so much child poverty.”

“And that,” she says, “Is what would make Dickens spin in his grave.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments