Inside Cellular Jail: the horrors and torture inflicted by the Raj on India's political activists

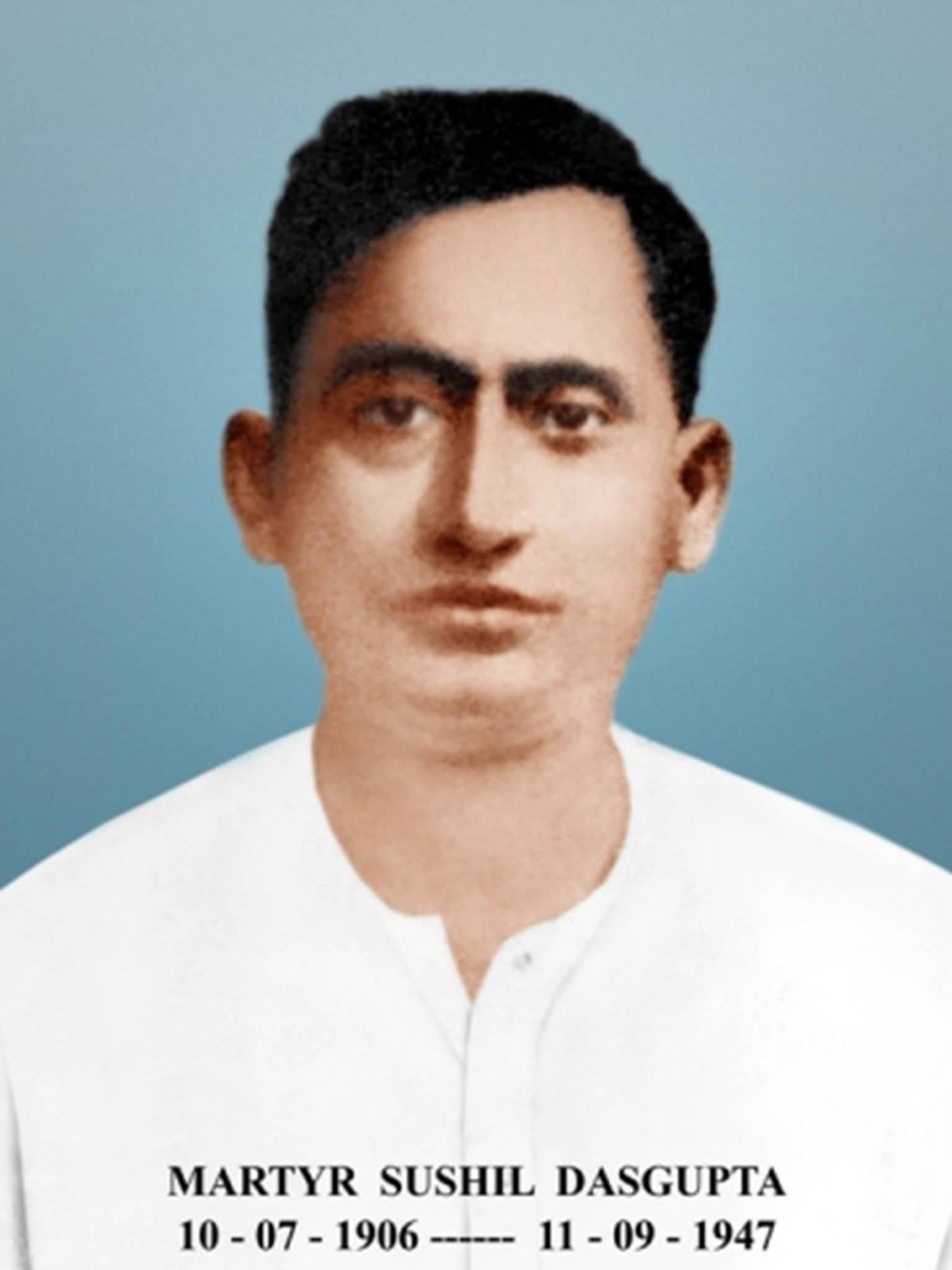

The penal colony, designed by the British to break people, would form one of the darkest chapters in India’s struggle for freedom. Robyn Wilson meets prisoner Sushil Dasgupta's son, who describes the treacherous treatment and soul-destroying slave work his father was forced to endure during his incarceration

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.After six hours of tortuous work under the fierce Indian sun, Sushil Dasguputa’s hands were covered in his own blood; his body exhausted from the relentless and monotonous motion of pounding coconuts to produce a backbreaking quota of fibre. His throat was bone dry. He stopped to ask the guard on duty for a cup of water but instead the overseer raised his whip, bringing it down over and over with a torrent of abuse. These were the working conditions awaiting political prisoners sent to the Cellular Jail – a brutal British penal colony on the Andaman and Nicobar Islands off the Bay of Bengal.

No matter how fatigued the inmates became, resting was not option. Sinister punishments awaited those who showed any sign of slowing. When not labouring they occupied separate cells, even their toilet breaks were strictly regimented. Any prisoner who had the need, would have to hold it for hours until they were permitted by the guards.

Like hundreds of other men on that island, years of Sushil’s life here would be filled with torture, hunger and loneliness. They would be worked like slaves. Some would go mad, others would be driven to suicide. This place would form one of the darkest chapters in India’s struggle for freedom.

***

Sushil was 26 years old when he was arrested and shipped out to the Andaman Islands on 17 August 1932. Like many other Bengali men at the time, he was a member of a political activist group called the Jugantar party, in Calcutta. Its cause was an independent India, free of British rule. With little other choice to raise funds for their political activities, Sushil, along with four other Jugantar members, robbed a bus at gunpoint. As they fled police intercepted them and a shoot-out ensued, during which Sushil was shot and eventually caught. His punishment was to be sent 800 miles away – out of sight and mind – to the Cellular Jail at Port Blair, capital of the Andaman Island, where he would join many of other exiled political activists.

By this point he knew what awaited him. The horror stories of the jail had begun to spread across mainland India. In Hindi, the jail was known as Kālā Pānī, translating literally as “black waters”. It referred to an ancient Indian taboo, which would cause anyone to lose their caste if they crossed the ocean away from their motherland, becoming a social pariah.

Between 1911-1921, the jail incarcerated the already famous freedom fighter Vinayak Damodar Savarkar. While studying in England, Savarkar had become involved in an Indian nationalist group called India House, which he went on to lead. He was arrested and jailed in 1910 for his connection to the group but it wasn’t until the following year, after escaping from prison, that he was shipped out to Port Blair.

Following his release, he wrote extensively of the awful conditions that he had faced, including the particularly harsh treatment by the cruel Irish jailor David Barrie, the self-declared “God of Port Blair”.

Savarkar wrote that as the gates of the prison shut behind him he felt he had “entered the jaws of death”. He continued: “I heard a whisper going round among the warders that Mr Barrie was coming. They seemed to have seen none more cruel and hard-hearted than he, and they watched my face to see what impression that name had made upon me.”

The jailor’s punishments were terrible, banishing prisoners to the living Hell of the oil mills. But while the prisoners suffered, Barrie and the other British officials lived in opulence across the water on Ross Island. Among the other buildings of their administrative headquarters they had their own tennis courts, a bakery, a swimming pool and a clubhouse for the officers.

***

Britain had started sending political activists to the islands when the Andamans were little more than an isolated backwater – years before the jail had even been constructed – in an attempt to stop rebellious figures such as Savarkar and Sushil from spreading revolutionary ideas.

After 1857, it had seemed a necessity. In May of that year, the people rose up in mutiny across north and central India against the sovereign power of the British East India Company (EIC). Starting apparently spontaneously against the British garrison in Meerut, it soon moved south to Delhi where rioters besieged the city.

It took a year and a huge British military deployment, but when the British Crown finally suppressed the rebellion, the fallout forced them to bring an end to the EIC’s reign. It was, however, a move that only gave birth to an equally brutal force – the British Raj.

One of the Raj’s first acts in 1858 was to set up a penal colony on the Andaman and Nicobar Islands and start exiling prisoners to it. It wasn’t until decades later in 1893, after the number of banished prisoners became unmanageable, that the decision was taken to build a high-security jail to house them at Port Blair.

Fortunately, for the British they had a labour force already in place. For 13 years the prisoners were forced under pitiless conditions to become the agents of their own imprisonment, as their jail rose up around them by their own hand, to open in 1906.

Surrounded by hundreds of miles of ocean in every direction, the Cellular Jail was designed with the sole purpose of keeping the men in isolation, and provided no hope of escape. At the centre of this massive three-storey structure stood a tall watch tower, out of which shot seven long concreted wings, like spokes on a wheel. Each wing had rows of single iron-gated cells – 693 in total.

It was here, when not working himself to the point of exhaustion, where Sushil would spend his time. He was locked up in small cell, measuring only 4.5m by 2.7m in size. To the back was a small iron vent. Out the front, all he could see was a brick wall compromising the rear of another wing. No other prisoners were in sight. Such solitary confinement was how the Cellular Jail got its name.

***

Being sent to this prison was the worst of punishments that the British Raj could devise. For Sushil, it was like “being transported for life to the valley of death”, says his son Anup, who tries to sum up what his father must have felt upon being given his sentence. “In those days the Andaman and Nicobar Islands were not considered as a part of mainland India. They were a foreign country. Transportation of the political prisoners to Andaman was conceived as if they were being sent for slow poisoning at that notorious island.”

After crossing the “black waters”, a journey that would last days, the daily grind that awaited Sushil was something that had been designed by the British to not only demoralise the men but completely break them. Their days would be monotonous and long. In the morning they would join a queue to be allocated a punishing work quota, the results of which would be scrutinised at the end of the day. If they failed to meet this quota they would be beaten or whipped. Sushil was given the job of endlessly pounding coconut husks to be used as fibre in certain fabrics, all under the watch of guards.

Famous freedom fighter Barindra Kumar Ghosh, who spent more than 10 years in the jail, described those who were given coconut or coir-pounding as living “in a state of suspense, as it were, between life and death”. Ghosh said each prisoner was given the dry husks of 20 coconuts, which would have to be repeatedly hit with a wooden hammer until soft. The skin would then be removed and the coconut would be dipped in water and bashed again.

He said it was only by “sheer pounding” that the entire husk would drop off, leaving the precious fibres. Men, like Sushil, carrying out this quota were expected to produce over two pounds of fibre a day.

Another gruelling task took place in the oil mill and caused many of the men to collapse from exhaustion. Their bodies covered only with strips of cloth, the prisoners had to manually turn a large wheel, which would press and squeeze coconuts for oil. They were expected to produce 30 pounds of oil a day, a huge amount that most were unable to complete in one work session.

It drove some to insanity. Anup recalls a story he was told of Jugantar party member Ullash Kar Dutta, who was said to have lost his mind after the punishment he received for refusing to produce such an amount.

“He refused to do it since this much of the quota is not done by a bull,” Anup says. “He was whipped badly and kept in a hands-up fetter position. When he was released after three days, he was unconscious and later on was found to be abnormal.”

Other men were driven to suicide. Indu Bhushan Roy, who was incarcerated in the jail 23 years before Sushil, was said to have been found hanging from the iron vent at the back of his cell, with a noose around his neck made from his own torn clothes.

Once the prisoners had finished the day’s arduous labour, their reward was to spend their evenings shackled on the floor in solitary confinement. Left alone in this iron-gated cell each prisoner would sleep beside two small, clay pots: one for water and the other to be used as a toilet. So small in size were the clay pots, that the men had a difficult time in using the empty pot effectively. Some were said to be so desperate that they resorted to using the bare floor.

Writing of his time there, VD Savarkar painted a horrific image of some prisoners having to sleep with their heads “near the nuisance [they] had committed”.

But this was all part of the jail’s sorrow-filled design. Guards were expected to treat the political prisoners in a way “that would break their spirit and completely demoralise them”, Savarkar recalled a high-ranking official from Calcutta saying.

***

Daily life became so dire for Sushil and his inmates that they decided to protest in the only way possible and during 1932-1937 many of them took part in a series of hunger strikes. On 3 January 1933, he and seven other men stopped eating and outlined demands for proper toilets and better food after being fed for months on a meagre diet of rice, bread and vegetables, which often contained small stones and inedible wild grass. Four months later, they took part in a mass hunger strike on 12 May 1933, which lasted 45 days. “Life in the Cellular Jail was nothing but torture, hunger and loneliness,” Anup says, explaining his father’s decision to take part in the strike. “They were desperate.”

But things were about to get worse. On the sixth day of the hunger strike the guards came for some of the men. A decision had been made among some of the British officials to start the long and brutal procedure of force-feeding the prisoners.

Taken forcefully from his cell, an inmate would be made to lie down on a bed, his head propped up with a pillow, his limbs held down by several attendants. A doctor would then insert a rubber tube into his nose and push it down his throat to pump a mixture of milk, sugar and eggs into his stomach. Prisoners, of course, fought the feeding – some by coughing heavily to dislodge the tube – which meant the whole, tortuous process took several hours.

For three men – Mahavir Singh, Mohan Kishore Namadas and Mohit Moitra – resistance came at a cost. They all died from force-feeding after milk seeped into their lungs, resulting in pneumonia.

Sushil and the rest of the inmates heard the news of the men’s deaths within a day or two, Anup says. “Their bodies were thrown in the sea with stones weighing down the bags.”

People on mainland India heard the stories too, but it wasn’t until four years later that Mahatma Gandhi – who underwent 17 fasts during India’s freedom struggle – successfully managed to intervene. In 1937, he and Rabindranath Tagore, a writer of the time who was involved in India’s freedom struggle, made an agreement with the head of the British administration in India, Lord Linlithgow, which paved the way for the prisoners to be released.

That same year the prisoners began to be repatriated to their respective states in India and the process of closing down the Cellular Jail began. Sushil was returned to a local jail in West Bengal on 18 January 1938 and the following year the Cellular Jail shipped out its last few prisoners. However, it wasn’t until 1943 that Sushil tasted freedom – something that was unfortunately short-lived.

By the time he was released, Gandhi’s non-violent movement was sweeping across India. “The revolutionaries could see that people of India had learnt how to die without any arms,” Anup explains how his father joined Gandhi’s movement. So groups like the Jugantar party agreed to put down their weapons.

Eventually on 15 August 1947, the Indian Independence Act was passed but the country was far from being at peace. “Calcutta was under severe communal disturbances at the time of independence,” says Anup. “The Father of the Nation [Gandhi] advised all his followers to carry out peace processions to restore communal harmony.”

So on 11 September 1947, Sushil took to the streets on Park Circus in Calcutta to lead a peaceful demonstration, a month after the Indian Independence Act had been passed and a year after four thousand people had died in the city during riots between Hindus and Muslims. Tragically, Sushil’s demonstrators were attacked and he was fatally stabbed. He had experienced only four years of freedom.

***

Anup says he was only three years old when his father “embraced martyrdom”, but he still remembers the flood of white flowers surrounding his father’s coffin. Many people came to pay their respects as his body lay in a hearse outside their house on Dixon Lane, which he says is now known as “Martyr Sushil Dasgupta Street”.

He remembers the various political group leaders being in tears as they approached his house to give condolences to his family.

The following year, Gandhi was assassinated by a Hindu nationalist called Nathuram Vinayak Godse. He was shot in the chest three times and died almost instantly. India’s fight for peace would continue for years to come under the leadership of its first Prime Minister and Gandhi’s close friend, Jawaharlal Nehru. During that time the suffering of the men who were incarcerated by the British Raj would remain largely unknown by the wider world.

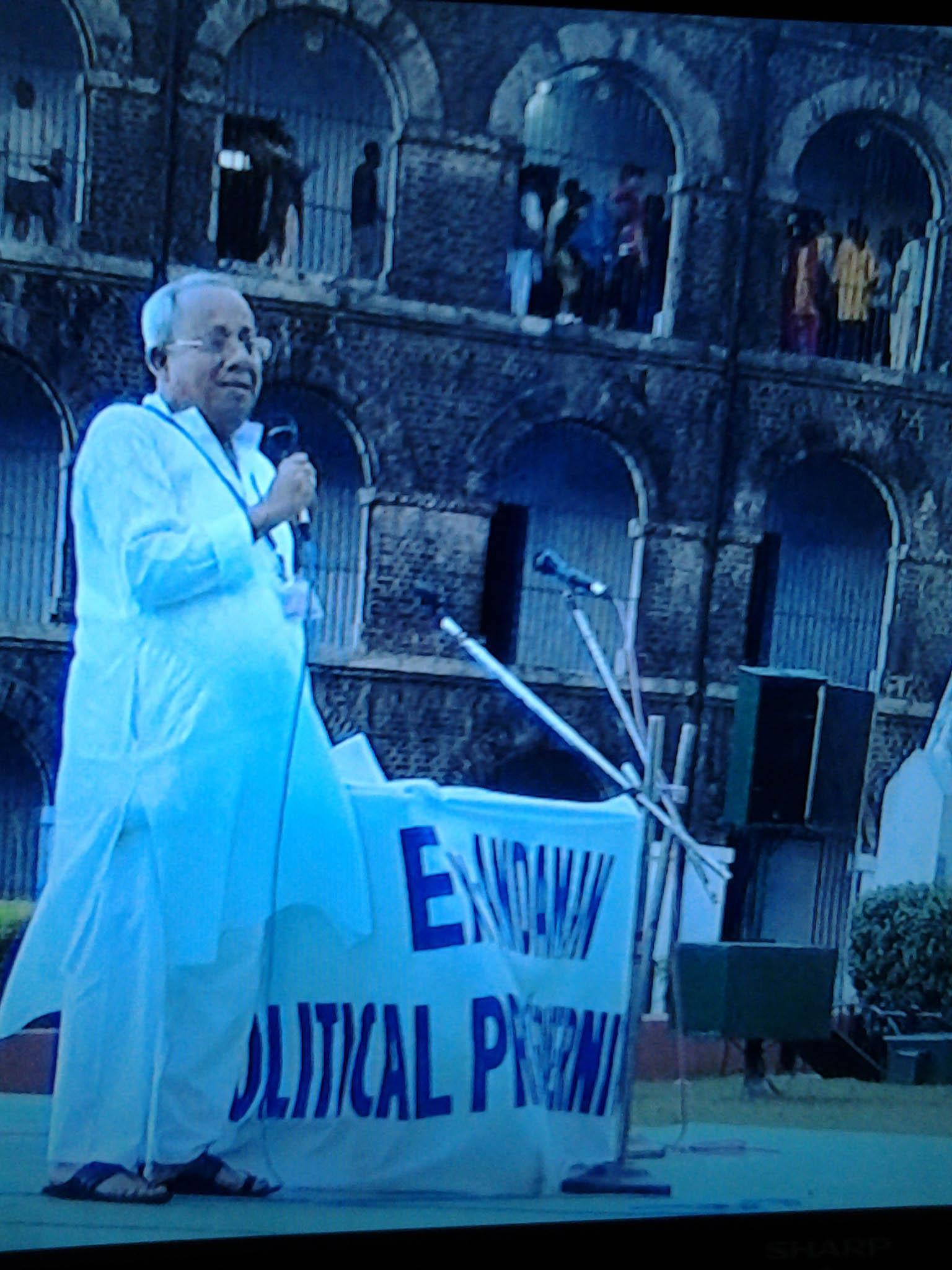

Today, however, the jail has become a “symbol of the freedom movement in India”, Anup says. He is now the working president of the Ex-Andaman Political Prisoner’s Fraternity Circle, a group made up of the sons, daughters and widows of the prisoners that helped to turn the site into a national memorial.

For Anup and thousands of other Indians, the history of this country’s struggle for independence would not be complete without an understanding of the Cellular Jail’s role, and the countless horrors that took place within its walls.

As part of our coverage on Partition, see Anil Dharker's story here

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments