Cavalese cable-car disaster: It's 20 years since a US aircraft killed 20 people in the Dolomites and still no one accepts responsibility

In 1998, a US pilot performs a 'daredevil' move and crashes into a cable car full of holiday-makers, killing them all. Godfrey Holmes asks why has no one been held to account for the tragedy?

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

What the British call a cable car – aerial tramways’ in other countries – is a very safe form of transport: technology practised, perfected, nowhere better than in the southern Alps of Ticino, Bolzano, and Alto Adige. Even when cable-hauled cabins or gondolas grind to a complete halt – sometimes for hours on end – disaster rarely ensues.

Another relatively safe way to travel is by aircraft. It is freefall that presents the greatest danger. What happens, then, when an aircraft in close proximity to a cable car causes one or other or both to go into freefall? Rewind the clock to 2.35pm on Tuesday, 3 February 1998.

High above his air-base in Aviano, in northern Italy, 30-year old Captain Richard Ashby revs a dated ‘EA-4B Prowler’ aircraft on a final training exercise before his promotion to fighter pilot. Today is not a repeat of the crew’s normal Nato reconnaissance flight to Bosnia – where the Yugoslavian war has waged for seven years already – more a farewell to arms.

In the seat next to Ashby is his decade-serving navigator, Joseph Schweitzer, whose duties are flight plan, mapping an exact route, altitude, and communications with the ground. Just behind him and his pilot are crew members: Captain Chandler Seagraves and Captain William Raney. Weather conditions are good. Very little low cloud. So good is the weather, there is even doubt as to what exactly this mission can accomplish.

After a '‘daredevil'’ negotiation of Lake Garda – some of whose surrounding mountains are 11,000 feet in height – and the rehearsal of a spar (a spoiler-augmented roll), Ashby skirts just west of Trento – capital of the autonomous Italian province Trentino – and proceeds 20 miles north-east, in the process entering the narrow Val di Fiemme, a valley dissected, as so often in the Alps, by its principal cable car.

By amazing coincidence, and probably unknown to any of the four men on board that Prowler, Cavalese, in the heart of the Dolomites, is already known to locals, historians, and newspaper reporters alike as the site of the most deadly cable car derailment since Andrew Hallidie’s 1873 invention of this mode of transport.

On 9 March 1976, 43 people – including 15 children – skidded 300 feet to their early deaths, trapped in their felled cabin, space additionally crushed by its own three-ton overhead assembly. Four lift officials were subsequently jailed for their gross negligence – which included de-activating that cable car’s safety system. Just one person, a 14-year old Milanese schoolgirl, survived that catastrophe.

Twenty-two years on, Captain Ashby skims low over Lago di Stramentizzo and at 3.06pm loses all radio contact with Aviano’s control tower. Nearby, villagers and visitors are already fed up of “the Yanks” flying so low at speeds over 500 mph: spooking the livestock; and strafing their farms, their rooftops, even their lidos. Nor have they forgiven their own Italian Air Force for severing electricity cables two years earlier, leading to major power outage.

Surely the marines are supposed to keep to an altitude higher than 2,000 feet? And even if they were to halve that restriction – a limit some US commanders strenuously maintain is still in force into 1998 – a flight height of 1,000 feet would still top hotels, apartment blocks, church spires, pylons, with ease. Why so low? Nato military’s wish and intention is to replicate the real, radar-jamming, conditions of entering a war-zone without being shot at.

When, at 3.12pm Captain Ashby unexpectedly encounters a newly loaded and moving cable car (painted bright yellow) seconds on in its own seven-minute journey to valley floor, he imagines this obstacle to be an ‘'optical illusion'’.No part of his briefing has included cable cars. He and Schweitzer have access only to US maps. Compatriots regard indigenous cartographers with some contempt. Besides, Schweitzer has set today’s altimeter at 800 feet. Surely the plane cannot ever have got as low as 300 feet? The altimeter must be playing up.

Whatever, pilot Ashby has absolutely no chance materially to alter his course. So he banks his aircraft suddenly upwards: a response that does not prevent – 30 seconds later – his rising right wing snapping those tourists’ essential lifeline, a sturdy cable, more than two inches thick. In sheer horror, Ranby grabs Seagraves by his shirt front.

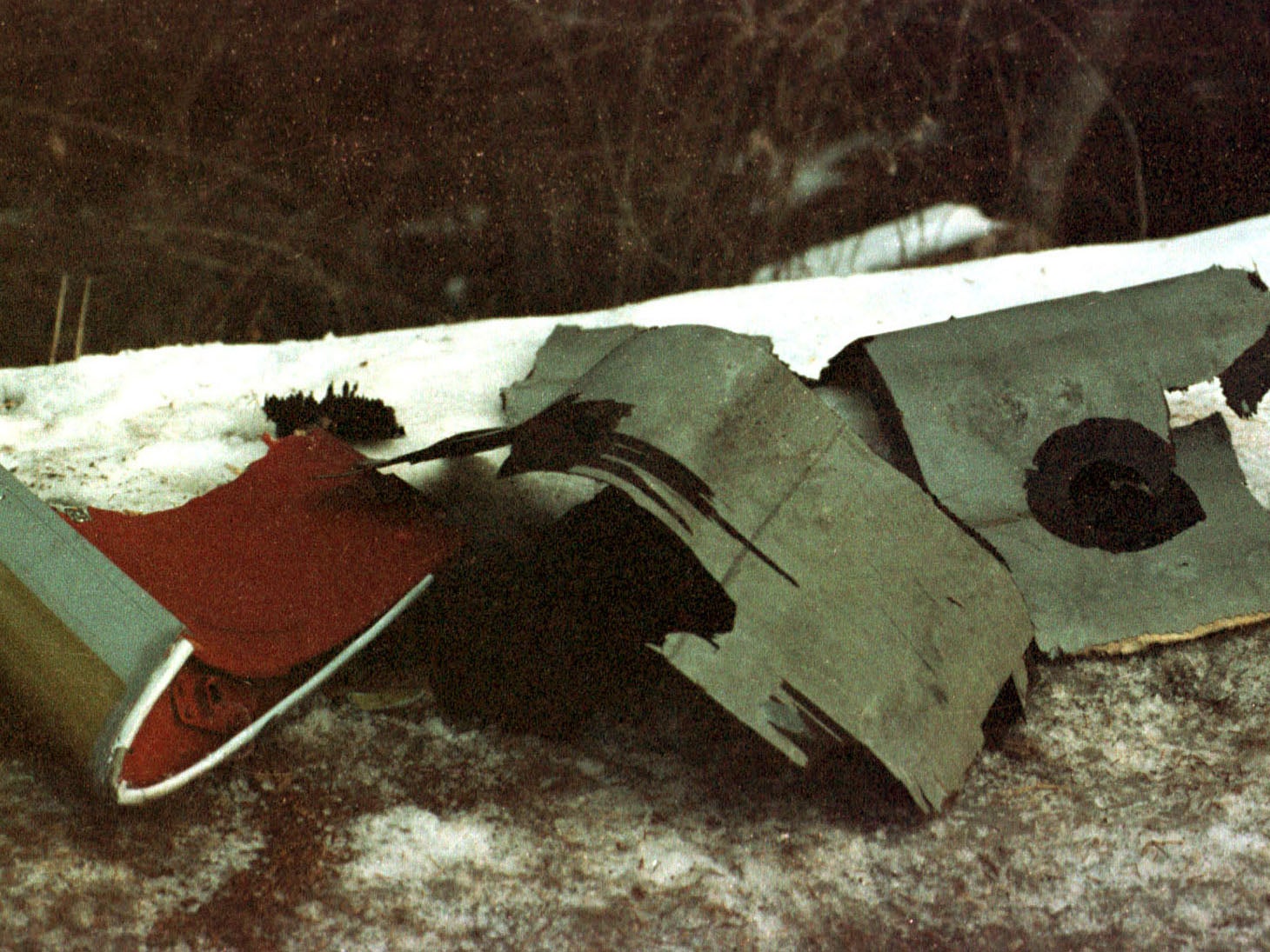

Navigator Schweitzer spies the stricken cabin lying in blood-spattered snow 250 feet below – but has to forgo any abortive rescue effort; determining instead to help get this now damaged aircraft back to Aviano, where control staff, back in radio contact, will be waiting for a jet with a split wing, broken tail, leaking hydraulic fluid; waiting indeed to reassure Ashby that his intact under-carriage will permit an emergency landing.

At 3.30pm, fatal hazard duly survived – survival is not an outcome available to all those tumbling tourists – Seagraves and Ranby obey military protocol by running towards the relative safety of a hangar. Looking back, they are a little surprised that neither Ashby nor Schweitzer are budging from their seats. They appear uninjured? Maybe they are in shock? Why is Schweitzer removing a filmed video-tape from his borrowed camcorder, replacing it with a virgin tape newly torn out of its tight cellophane wrapping?

Could it be all four crew members are for the high-jump? Not only is it strictly forbidden to perform stunts like under-flying cables. Not only is it a grave offence to damage a US aeroplane on manoeuvres. the crew is also learning what they sort of know already: not one soul has survived in the “we may have hit something” cable cabin.

The startled crew additionally learn that, although “only” three Italians have died (eight German nationals, five Belgians, two Poles, one Austrian, and one Dutch are also perishing), Italian politicians, broadcasters, journalists, citizens, are already livid upon hearing the breaking news. And they are baying for justice. Prime minister Romano Prodi calls the disaster: “A terrible act: a flight practically scraping the ground!” Italian president Oscar Luigi Scalfaro shares his people’s outrage. Local observers add: “Rules of [mock] engagement have been systematically and calamitously disregarded.”

Nor does any Italian believe pilot Ashby will ever be held to account for the disaster. On the contrary, there will be an almighty cover-up. And straightway the Americans play into their critics’ hands: not only by reserving justice to United States’ jurisdiction, but, insultingly, handing over this complex procedure to the very marine corp, whose members were involved from the beginning.

Public relations is a deft – maybe devious – art. US generals and flight crew soon adopt the vocabulary of minimisation. Ashby was merely on “a mishap” flight: an errand impeded by “instrument malfunction”, adding up to a “regrettable incident”, a “pure accident”, a “forced last-minute diversion”.

US marine Brig Gen Guy Vanderlinden, deputy commander of Nato's strike and support in southern Europe, is not keen to apportion any blame. In fact, all through March 1998, secret and internal findings – findings very critical of the American crew, findings garnered by senior generals Pace and de Long – are suppressed within a Washington DC archive until the editor of La Stampa successfully argues for their release in July 2013.

Only president Bill Clinton deviates from the “Please Sir, it wasn’t me Sir!” script by sending his deepest condolences to both families bereaved and the tourists’ host nation. “We shall unambiguously shoulder responsibility for what has happened,” he assures whoever is listening. At the same time, America’s 1997 ambassador to Italy, Thomas Foglietta, is dispatched to Cermis to kneel and pray beside the wreckage.

Fast forward a few months. The US grudgingly reimburses the $60,000 each bereft family had been awarded by the Italian government in the interim; rather tactlessly adding to each “settlement” $5,000 per family, earmarked for the repatriation, burial, cremation, of their loved ones’ bodies.

At Cherry Point, North Carolina, a “sane and well-behaved” Captain Ashby “with no history of drugs or psychological problems” is arraigned before a court martial for involuntary manslaughter and negligent homicide of 20; also for a number of associated charges that add up to a minimum penalty of 200 years imprisonment. But on 4 March 1999, after a trial lasting just 14 days – and despite clear technical evidence that neither the altimeter nor the G-meter were faulty during his final flight – a jury of nine acquit Ashby on all counts. His relatives cheer to the rafters. Italian observers, not surprisingly, are as stunned as they were disappointed.

John Eaves, lawyer for the seven German victims, speaks for many when he splutters: “I don’t understand this verdict. There’s no justice in the world...”

Italian deputy, Ermanno Jacobellis, follows up with this comment: “It’s a shame these two men were acquitted. Their responsibility is clear and direct.”

Anybody who has witnessed the most recent US trials for killer police officers, militant white supremacists, also corrupt prison guards, might not have been so astonished at this outcome.

Meanwhile, Schweitzer rejoices that the military prosecutor has automatically dropped all charges against himself: his delight confined only by the discovery of Seagraves accepting a plea-bargain and “telling all”.

Therefore, in May 1999, there is a second court martial. Is this a belated sop to troublesome Italians? Ashby and Schweitzer are accused of perverting the course of justice, also conduct unbecoming of an officer and gentleman. And not only are they both found guilty: Ashby sentenced to six months’ imprisonment, reduced to 19 weeks for good behaviour.

Both men are dishonourably discharged from the marines and deprived of all consequent benefits to which they might have been entitled. Inevitably both officers lodge appeals on 12 counts: two concerning ‘'inadequate'’ evidence presented to court and too harsh a sentence. Of interest, jurors are never told Schweitzer has, from the start, entered a guilty plea-bargain in order to avoid incarceration.

Neither Ranby nor Seagraves are charged with any offence. Nor does Nato ground command face any punishment, even though many think its ineptitude is manifest. Nor do the Italians turn against any of their own leaders for giving US aviators so much – or so little? – headroom.

And despite Schweitzer's plea bargain, the Prowler’s navigator stands outside court and merely says: “My immediate plans are basically to wake up tomorrow morning and not have to deal with this [matter] for the first time in 14 months.”

Too little punishment, far too late in the day, for aggrieved Italians. They no longer want US aircraft to fly from Aviano or anywhere else. And correctly, they realise that nobody, two, 19, 20, years later is ever going to be held to account for the actual severance of that gondola’s cable. Further, nobody is ever going to make meaningful reparation. Nor is anybody ever going to admit issuing dangerous instructions, supplying the wrong maps, being content with haphazard de-briefing. And why has a sister Prowler’s crash in Yuma, Arizona only two years earlier – a crash that killed all four people on board – not been taken into account?

Altogether: too many questions, too few answers. And should any student of disaster be complacent enough to assume “Strage del Cermis” (“the Massacre at Cermis”) could not happen again, he or she has only to recall the sinking of the Costa Concordia, on 13 January 2012. Almost worse, from a lay investigator’s standpoint, there is the Germanwings’ Flight 9525 plunge into France’s Massif des Trois Évêchés, on 24 March 2015: its spree-killing co-pilot apparently wanting to commit suicide. More rocks. More hard places.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments