Cari Mora: How the new thriller by Thomas Harris silences those lambs

‘Cari Mora’ is not only Harris’s first novel since 2006, it’s his first in four decades not to feature Hannibal Lecter. However, cannibalism remains a central fascination for the author. As MM Owen declares, the universe is forever dining on itself, but figures such as Clarice Starling and Cari Mora want to interrupt the meal

In his “perfectly natural history” of cannibalism, the zoologist Bill Schutt takes until page one to reference Hannibal Lecter eating a census-taker’s liver with some fava beans and a big Amarone. Lecter might be literature’s most famous serial killer; he is without doubt its most famous cannibal. Lecter’s creator, Thomas Harris, recently published Cari Mora – his first novel in 13 years, and his first in 44 years not to feature the character made famous by an unblinking, enunciating Anthony Hopkins. And yet: despite Lecter’s absence in Cari Mora, the cannibalism persists. We meet Mr Imran, “a large, impassive man with a cauliflower ear”. A character recalls that Imran is “a biter”, and “could not always help it”. At the end of the chapter, sat in his car, Imran eats a human kidney, raw.

Lecter is absent, and yet here he lingers, a ghost at the cannibal feast. Why? Why can’t Harris help but include a glimpse of this dark appetite? Because at the core of Harris’s hugely popular horror fiction has always been a vision of the cosmos as fundamentally self-devouring. As Schutt outlines, cannibalism occurs across “the entire animal kingdom”.

It is common among invertebrates, fish, and reptiles, and it is observable in many mammals, including our closest cousins, chimpanzees. Such cannibalism generally occurs for reasons “that make perfect sense from an evolutionary standpoint: reducing competition, as a component of sexual behaviour, or an aspect of parental care.” (On parental care: if you want nightmares, go and google how the mother black lace-weaver spider feeds her young.)

In the figure of Lecter, though, Harris elevated cannibalism into a sort of commentary, or performance, that reflects the real nature of reality. It is the essence of violence, but it is also simply predation in all its forms, including the sexual. Lecter embodied this greedy spirit, and Harris can’t shake his famous villain; in Cari Mora, his shadow is everywhere. Lecter’s devouring of Clarice Starling’s spirit at the end of Hannibal is even given a rerun, suggesting that perhaps Harris regretted this final, polarising act of character consumption.

Cari Mora, Harris’s new novel, has two plots. Firstly, there is a battle between two criminal outfits to recover $25m worth of gold. This gold is locked inside a booby-trapped safe buried beneath an opulent waterfront mansion in Miami’s Biscayne Bay. Secondly, there is a far more familiar Harris motif: violent psychopath pursues attractive young woman. The leader of one of the gold-hunting gangs, Hans-Peter Schneider, has a day job that involves kidnapping such women, mutilating them, and selling them to a super-wealthy Mauritanian man with depraved sexual tastes. The Colombian-born Cari Mora, a former child soldier conscripted into Farc at the age of 11, is caretaker at the Escobar house. Hans-Peter’s pursuit of her runs until the novel’s penultimate page.

These two dramas – the race to acquire Escobar’s gold, and Hans-Peter’s violent designs on Cari – don’t entirely hang together. Though Cari Mora is composed in Harris’s usual style – precise and wintry, occasionally oracular – most of the major players in the gold-digging story are too thinly drawn to ever become truly interesting, and a couple of backstories with the seeds of subplots wither away. Where the two stories connect, though, is in linking and mirroring different sorts of biological appetite.

There is no mercy; we make mercy, manufacture it in the parts that have overgrown our basic reptile brain. There is no murder. We make murder, and it matters only to us

In 2005, the journal Gothic Studies declared that “Thomas Harris is to contemporary Gothic fiction what Bram Stoker was to Gothic fiction in the 19th century.” They certainly resemble in each other in one way: both of their famous characters are men who like to dine on human flesh, and whose act of dining symbolises far more than satiating caloric need. Taken as a whole, Cari Mora reiterates Harris’s master metaphor: an unending, cosmic cannibalism.

Everything Harris has ever written is filled with the goings-on of other species. Often, these goings-on are predatory, studded with insights into how a given creature does violence. (In Hannibal, we learn that “tusked pigs instinctively disembowel when fighting the upright species, men and bears.”) Throughout Cari Mora, animals are a constant. Barely a page goes by without a frog peeping, a bird whistling, a manatee surfacing, a firefly winking, a stingray flapping. Above all, Cari Mora is filled with birds: “ibisses, egrets, pelicans, ospreys, herons”. And as in the rest of Harris’s novels, the narrative is studded with glimpses of predation. Fish swallow insects; ants are drawn to the protein of dried blood. We see pelicans “heading for a fish drive,” “crows mobbing a hawk,” two cormorants stalking some mullet.

At one point, a character in Cari Mora stands at the seawall of the Escobar house and watches a school of crevalle jacks chase some mullet until there are “pieces of fish flying in the air”. “Like us,” he thinks; “Kill and gobble like us.” Later, at an assisted-living facility, a “preacher of advanced age” holds a Bible and reads to his congregation from the Book of Ecclesiastes: “... men might see that they themselves are beasts ... For that which befalleth the sons of man befalleth beasts; as the one dieth, so dieth the other; yes, they have alone breath; all are of the dust and all turn to dust again.” The preacher’s congregation are gathered in the garden, and the faithful are comprised of one elderly human, “four dogs, a cat, a small goat, a free parrot and several chickens”. Harris occasionally peels back his thematic curtain a little too much, and these two moments, taken together, are a good example. Cari Mora says it very clearly: humans are animals. Creatures like all the rest. And as the novel never lets us forget, what creatures do above all else is kill and gobble. This demolishing of human exceptionalism, reminder of the brute biosphere, recalls the end of Red Dragon, when Will Graham recalls a visit he took to Shiloh, Western Tennessee – site of a bloody 1862 American Civil War battle. Graham muses that Shiloh reflects “the indifference of nature ... there is no mercy; we make mercy, manufacture it in the parts that have overgrown our basic reptile brain. There is no murder. We make murder, and it matters only to us.”

The American author Thomas Ligotti has argued that all modern horror writing – from Ann Radcliffe through Edgar Allan Poe through HP Lovecraft – is inspired by a biologically derived pessimism. Call it the disillusionment of Darwin. Effective horror is always, in Ligotti’s view, motivated by the capacity “not only to place humanity outside the centre of the Creation but also to survey the universe itself as centreless and our species as only a smudge of organic materials at the mercy of forces that know us not”. Ligotti’s thesis is absolutely true of Harris. (“We are elaborations of carbon,” Lecter tells Clarice, in a letter.) Continuing the framing of all of the Hannibal novels, in Cari Mora, we observe evolution’s ravenous menagerie, and a perpetual, ambient feeding frenzy. Like any creature, humans are essentially consumable, and thus potential prey. In Hannibal, Mason Verger wants to kill Lecter by feeding him to wild pigs, and is killed when a sister stuffs a moray eel down his throat. In Cari Mora, saltwater crocodiles dine on men, and more than one corpse is gnawed by crabs. In a flashback of Cari stumbling upon a corpse in the Colombian jungle, we see “buzzards flapping away, heavy from their meal”. The murderous Hans-Peter recalls revisiting a woman he dumped in the bush and finding her “warmed wonderfully – warmed warmer than life by the larval mounds.”

William Blake, that great chronicler of innocence, is a constant touchpoint with Harris. It is innocence, and its cousin, frailty, that is always under threat, and always protected by his heroes

Such cross-species feasting functions as a sort of metaphorical ontology. If there is no bright line between species, then everything is cannibalism, and nothing is cannibalism. Meanwhile, the meal is never-ending. This has always been the ouroboros at the heart of Harris’s gothic horror: reality’s true condition is simply matter, devouring itself. All of it driven by the pure force of the senses and what they crave. That there is a dark sort of elegance to this is partly what made Lecter unique; the original genius of him wasn’t that he was amoral, but that he replaced morality with aesthetics, with pleasure – and that it charmed. Hannibal was an unreal representation of his type; in Hunting Humans, the serial murder expert Elliott Leyton writes that real serial killers are “usually without intellectual or physical attainments”; “they are often uneducated and virtually illiterate”; “their tastes are anything but elegant”; “in sum, they are dull, unimaginative, socially defective, vengeful, self-absorbed and self-pitying human beings”. Lecter is the perfect inverse of all this. But it works, because fiction’s entire function is to tell the truth even as it lies. What Lecter represents is not real psychological profile but a worldview that is at once cruel and rather pretty. Lecter embodies a godless epicureanism, the elevation of the Goldberg Variations above human life. This is, in truth, the natural end of aesthetics. “Taste and smell are housed in parts of the mind that precede pity,” he explains to Clarice Starling, while sipping lillet with a slice of orange.

In Red Dragon, the protagonist mentions what is today semi-common knowledge but what was then a fresh insight from FBI psychological profiling: “sadism to animals as a child” is a common precursor to violent psychopathy. By contrast – and in opposition to the cosmic cascade of imploding appetites that power his fictional universe – the virtuous characters in Harris’s fiction always care about animals. The standout example is Clarice Starling and her lambs. Starling’s drive to rescue murder victims is presented as a sort of existential quest, a need to insert at least brief spells of silence into her memory of lambs screaming on their way to the slaughter. William Blake, that great chronicler of innocence, is a constant touchpoint with Harris. It is innocence, and its cousin, frailty, that is always under threat, and always protected by his heroes. In Hannibal, Barney, another of Harris’s good guys, protects a wounded pigeon. In Cari Mora, Cari works part-time at the Pelican Harbour Seabird Station helping rehabilitate birds nursing injuries that will kill them in the wild. At one point, in an echo of Starling with her little lamb, Cari jumps off a boat and wades into some mangroves to rescue an osprey tangled in some fishing wire.

A pitiless cosmos, devouring itself; a will to protect the weak, the about-to-be-devoured, whatever species they belong to. This old dualism of Harris’s – psychopathic killer and determined FBI agent; order and chaos – provides the core tension in Cari Mora. It drives the encounter between Hans-Peter and Cari, which is not only the most memorable thing in the book, but clearly the section in which Harris was most interested. (The gold-digging plot wraps up rather abruptly, and the last three chapters focus entirely on Hans-Peter hunting Cari.) While Cari struggles to repair the wings of hurt birds, Hans-Peter dreams of reducing her to “a stump with a single branchy limb” “with which to provide pleasure to her masters”. She is blind compassion; he is fastidious sadism.

When they aren’t eating, the thing animals are most interested in is mating. And in the Harris cosmos – which is almost entirely absent of men and women having normal, healthy, edifying sex – erotic craving is another part of the feeding, just hunger felt in a different set of organs. At its most benign, this is an ambient, helpless lust that leaves people (mainly men) bitter and envious. At its worst, it is Harris’s serial killers, who feed their debased erotic fantasies with the flesh of women. An eroticised predation is present again in Cari Mora, with Hans-Peter’s pursuit of Cari. (The condition of men not raping women, meanwhile, is labelled “civilisation.”) It seems bold of Harris to have conjured another violent-psychopath-pursues attractive-young-woman setup. It is inevitable that this one will be compared to his famous original, the Lecter-Starling (or Hopkins-Foster) saga. The safer thing, surely, would have been to find a different sort of horror plot. What is he doing here? Why revisit this setup?

This is a sort of manic, infantile madness one could never imagine with Lecter, who is so preternaturally composed that his pulse rate doesn’t rise when he’s biting a nurse’s tongue off

A clue, I posit, lies in Cari Mora’s blurb: “Monsters lurk in the crevices between male desire and female survival. No other writer in the last century has conjured those monsters with more terrifying brilliance than Thomas Harris.” Sidestepping the bold central claim (in the whole last century?), what is left unsaid here is that the last time we saw Harris’s monsters in the open, many of his dedicated readers were profoundly let down. In 1999’s Hannibal, the culmination of the Lecter-Starling saga on the page, the tale ended with what John Lanchester described as the novel’s “moral algebra” being “spectacularly abandoned”. In short, Lecter’s worldview finally swallows Starling whole. She, tireless pursuer of murderers, fierce moralist, abandons it all. The pair move to Buenos Aires and become lovers. Some (including Stephen King) rather enjoyed the lurid leap of this, the devastating melodrama of Lecter’s icy allure finally triumphing and sucking a protector of lambs into the amoral void. But many loathed it; not just for its sheer oddness – at one point, Starling actually breastfeeds Lecter – but for the deeper sense that it was a betrayal of Starling’s character. Jodie Foster felt so strongly about this that she didn’t reprise her role as Starling for the movie adaptation.

Could this have been on Harris’s mind here, when he was writing Cari Mora? There is a moment in The Silence of the Lambs where Miggs – Lecter’s cell neighbour at the Baltimore State Hospital for the Criminally Insane – flicks semen into Starling’s face. Lecter finds this “unspeakably ugly”; that night, he kills Miggs by talking him into swallowing his tongue. Early in Cari Mora, meanwhile, Hans-Peter makes a plan to creep up on Cari while she is asleep and masturbate over her cheek, “little facial, what the hell?” Even if the similarity of these sexual transgression is pure coincidence, it highlights neatly the key difference between Lecter and Hans-Peter. Unlike the vast majority of real-life male serial killers, Lecter himself is no misogynist. Not one of his murder victims are female. He is, in fact, something of a gentleman. Without his strange chivalry, he and Starling’s infernal romance could never have come to fruition.

Hans-Peter, meanwhile, is a dedicated misogynist of the most depraved sort. And his misogyny is but one aspect of a variety of ways in which he has none of Lecter’s demonic charisma. Constantly composing German ditties in his head, Hans-Peter is absurd, comic, perversely childish. He is devoid of Lecter’s scholarly refinement, never pausing to offer a bit of chilling, arresting atheism. Hans-Peter is also properly unhinged – to a degree that doesn’t always quite work, the novel’s voice becoming brittle and forced in portraying it. At one point we see Hans-Peter sat on the floor of his shower, blowing an Aztec death whistle until he collapses; shortly afterwards, he pours a whole carton of milk over his head. This is a sort of manic, infantile madness one could never imagine with Lecter, who is so preternaturally composed that his pulse rate doesn’t rise when he’s biting a nurse’s tongue off.

Hans-Peter is, in short, utterly without charm. Throughout the novel, Cari is never anything other than repulsed by him. Many readers saw Starling’s capitulation at the end of Hannibal as not only silly, but a sort of feminine defeat. There is no such defeat in Cari Mora. Hans-Peter and Cari do not move to Buenos Aires and go to the opera and live sexually ever after. Some of the basics of the scenario feel like a rehash of Starling’s arc. Like Starling, Cari is an orphan, with the psychic scars to show for it. (Her family was massacred by paramilitaries in her second year as a soldier, and “when she heard she could not speak aloud for two weeks”). Starling had her screaming lambs; Cari Mora is haunted by the memory of seeing two lovestruck 13-year-olds executed in the Colombian jungle. But unlike Starling, this damage does not leave her vulnerable to the dark persuasions of a serial murderer. Cari is stoic, preternaturally unflustered by horror. The novel is named for her, not her murderous pursuer – a privilege never bestowed on Starling. The pursuer is almost laughably unworthy of her actual affection. “Bound wrists appeared a lot in Cari’s dreams,” we read; but when her wrists are actually bound in real life, she ingeniously escapes them. And when Cari is asked whether she wants “a guy,” her response, given a melody, could be a Beyoncé lyric: “I want to own the front door. Then maybe I invite somebody in it.”

It’s tempting to say that this is Harris for the #MeToo era, but every one of his novels has featured what is commonly termed a strong female protagonist. This was chiefly what the end of Hannibal betrayed, for many. Cari is what is commonly termed badass, but so was Starling. The difference is that here, with a plot that mirrors many of the rudiments of his most famous one, Harris plays out a very different final act. Lust’s hungry gaze, and the rage that attends the rejected male, was always present in the Hannibal novels. Throughout, Starling is relentlessly ogled, and her career at the FBI is ultimately ruined by a man who never forgave her for spurning his advances, and loathed “the picky, petty homemaking skills of a woman” that made her such a brilliant agent. Cari is ogled too, but at the end of the novel named after her, she very clearly refuses to acquiesce to the manipulation of a violent male. Unlike the Hannibal novels, we see no final, masculine triumph of the sort of blind force that Simone Weil read into the Iliad.

It is impossible not to ask: is this depiction of Hans-Peter and Cari, with its obvious echoes of Lecter and Starling, Harris reacting against the critiques of where he ended the latter arc in Hannibal? Is it an admission of narrative regret, even an attempt to partially repair that damage? Ridley Scott’s adaptation of Hannibal removed that sexually-ever-after ending, because Scott found it preposterous. Harris was apparently not only unoffended by this, but so convinced by Scott’s scepticism that he helped the screenwriter, Steve Zaillian, write the movie’s new ending. Did Harris have his doubts even then, less than two years after the book went to print? Is this why Hannibal Rising was so heartlessly dashed off? This is all scepticism, not least because Harris hasn’t given an interview in decades. But the uncharitable reading here would be that what Harris really wanted to do with Cari Mora was offer a coda or alternate ending to the Lecter-Starling arc – and he had to find a rather ordinary thriller plot in which to embed it.

The animal care of Harris’s novels is a charity of this kind. A sort of defiant, doomed, selfless stand against the animal kingdom’s mindless gobbling

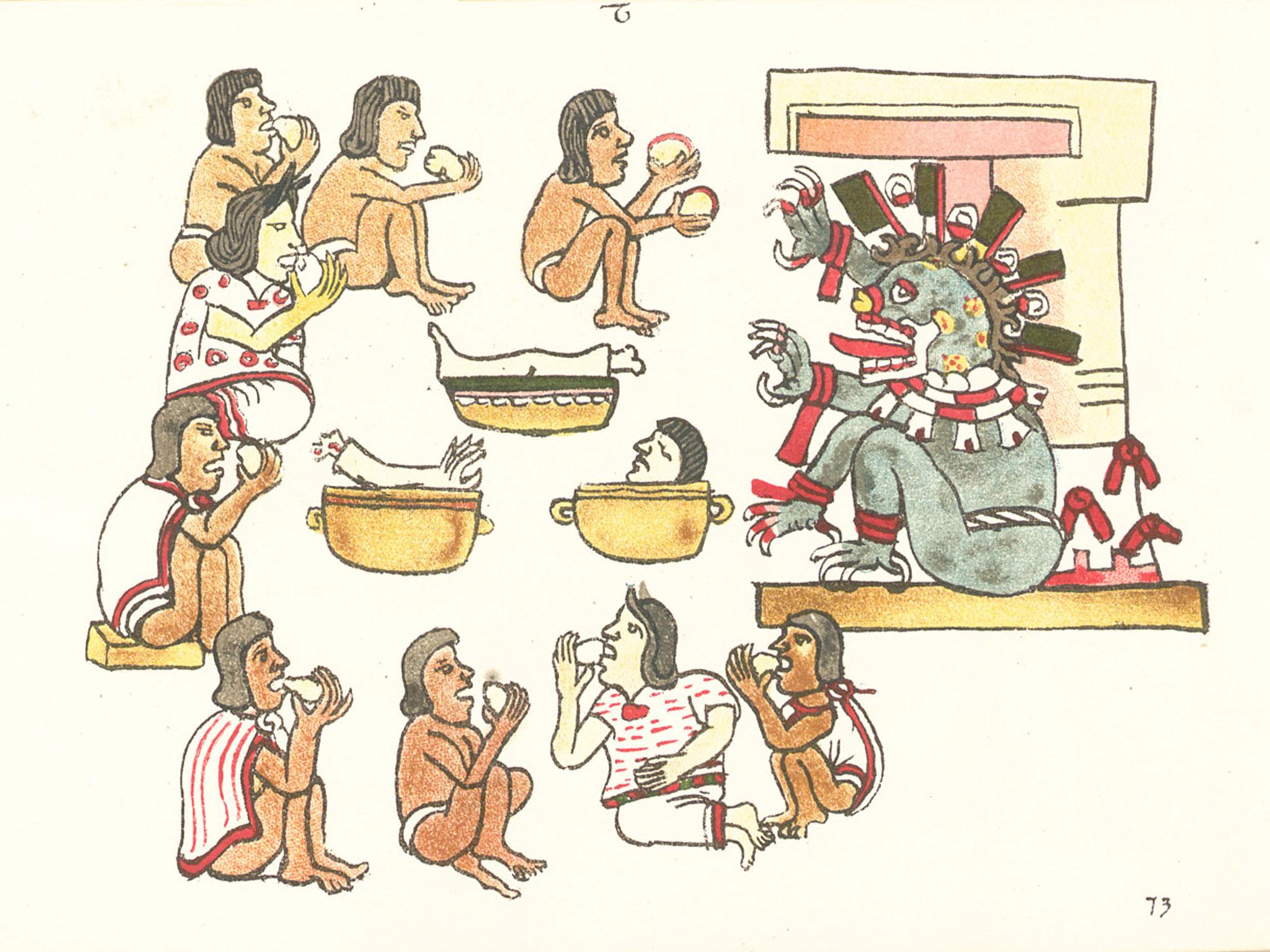

“A thousand birds murmuring and stirring, strident peeps from some chicks until they were quieted with a snack of regurgitated fish.” Cari Mora reiterates Harris’s Ligottian cosmos. It is a world where life and matter cannibalizes itself in a storm of appetites; where the true soundtrack of reality is digestion. The greed for gold and the greed for sexual satisfaction are rolled into one big human hunger, and together they are what drag Cari through a harrowing few weeks in what has already been a pretty harrowing life. The book’s atmosphere is biology, happening. That disillusionment of Darwin. Harris, who grew up in the Bible Belt, always clearly enjoyed himself with Lecter’s godlessness (the flesh-eating psychiatrist “collects church collapses, recreationally”). In Cari Mora, characters constantly say Dios se lo pague (God bless you) to one another, even as the novel’s events are quite clearly not being overseen by a benevolent actor – and indeed any such benevolent actor receives fewer mentions than the gods of that committedly cannibalistic civilisation, the Aztecs.

And yet: as in the rest of Harris’s novels, it is resisting the merciless storm of predation, of organic matter consuming its other iterations, that is made noble. According to a reporter who in 1999 tracked down Harris’s childhood acquaintances, Harris struggled to makes friends in hard-bitten, Fifties Mississippi because “he wasn’t athletic at all, and even less interested in killing animals”. The bird rehabilitation centre that Cari works at is real, and in the book’s acknowledgements Harris calls it a “remarkable, humane institution”. Despite having stacked the deck against himself with admirable enthusiasm, Harris’s heroes all refuse to accept that fleshy vulnerability is the sum of things. They want to protect the meek, and minimise easy slaughter. The universe is forever dining on itself, but figures like Starling and Mora want to interrupt the meal.

In 2001, when Harris was a rather more immediate part of the fiction landscape, the critic David Sexton wrote that he “easily stands comparison with the great melodramatists of the past: Bram Stoker, Conan Doyle, Wilkie Collins or Edgar Allan Poe, say, perhaps even Robert Louis Stevenson. He will last as they have lasted.” Readers will make up their own about this. But if his melodrama does survive, it will be because it makes grand this battle: blind, devouring cosmos, simple recycling of matter, versus a belief that the vulnerable deserve protecting, that even if the war is always being lost such small battles of compassion are worth the fighting. This belief, as Lecter would delight in reminding us, can only ever be an assertion, a sort of faith. This is a stretch, but could it be that Harris, the old Southerner, didn’t shake all of his Christianity? The cover of Cari Mora is festooned with an image of Our Lady of Charity, Catholic patroness of Cuba and that nation’s quintessential religious icon. (Miami is, of course, a Cuba away from Cuba.) “Charity,” in the biblical sense, is a fudged translation of the ancient Greek agapē, which means something more like selfless love. The animal care of Harris’s novels is a charity of this kind. A sort of defiant, doomed, selfless stand against the animal kingdom’s mindless gobbling.

What stops Harris’s books from being a pure hellscape of appetite is mercy, care. This time round, his lady of charity – Cari is short for Caridad, Spanish for charity – resists pandemonium. History’s most fervent opponents of cannibalisms, we might note, were all Christian missionaries. They in turn advocated a form of cannibalism that was not only consensual but strongly encouraged, because it freed us from this animal gauntlet, Christ’s transubstantiated flesh and blood lifting us at the Last Judgement into a place where we weren’t condemned to the iron logic of the physical. Today’s Harris, it would seem, wants the feast to go differently. It is a rather ordinary thriller, but Cari Mora is interesting for being a sort of repentance: Having served Starling to a man dripping in Satan imagery, he now wishes he could snatch her, and the silence of her lambs, back from between his elegant jaws.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments