The mysterious Cambridge library tower, supposedly full of banned books, is opening to the public

Jessica Gardner, Cambridge University’s librarian, reveals how a new exhibition at its famous tower will uncover the texts telling the story of our national life

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It has inspired long running myths – notably that it hides a stash of Victorian pornography – is home to 10 storeys of books, has given rise to some dark tales of famous literature and has dominated the skyline of one of the nation’s most historic university cities for almost a century.

At 157ft tall and 17 floors, Cambridge University Library’s tower can be seen for miles around but has largely kept its secrets to itself and its contents (approaching one million books) have given rise to much speculation.

But now in a new free exhibition, Tall Tales: Secrets of the tower, we reveal some of the truth about what the great skyscraper really holds.

Just over a year ago, the first question at my interview for the job of Cambridge University librarian asked about the importance of a legal deposit – or copyright – library.

The factual answer is that, by law, it means we are entitled to receive a copy of every book that is published in the United Kingdom and Ireland. But the answer that speaks to my passions as a librarian and archivist, is that it means we are home to a collection that tells the remarkable story of our national life through the printed word.

In the exhibition, which opens on 2 May, we lift the lid on two centuries of popular publishing in the UK, received under the Copyright Act and held in the tower since the building opened in 1934.

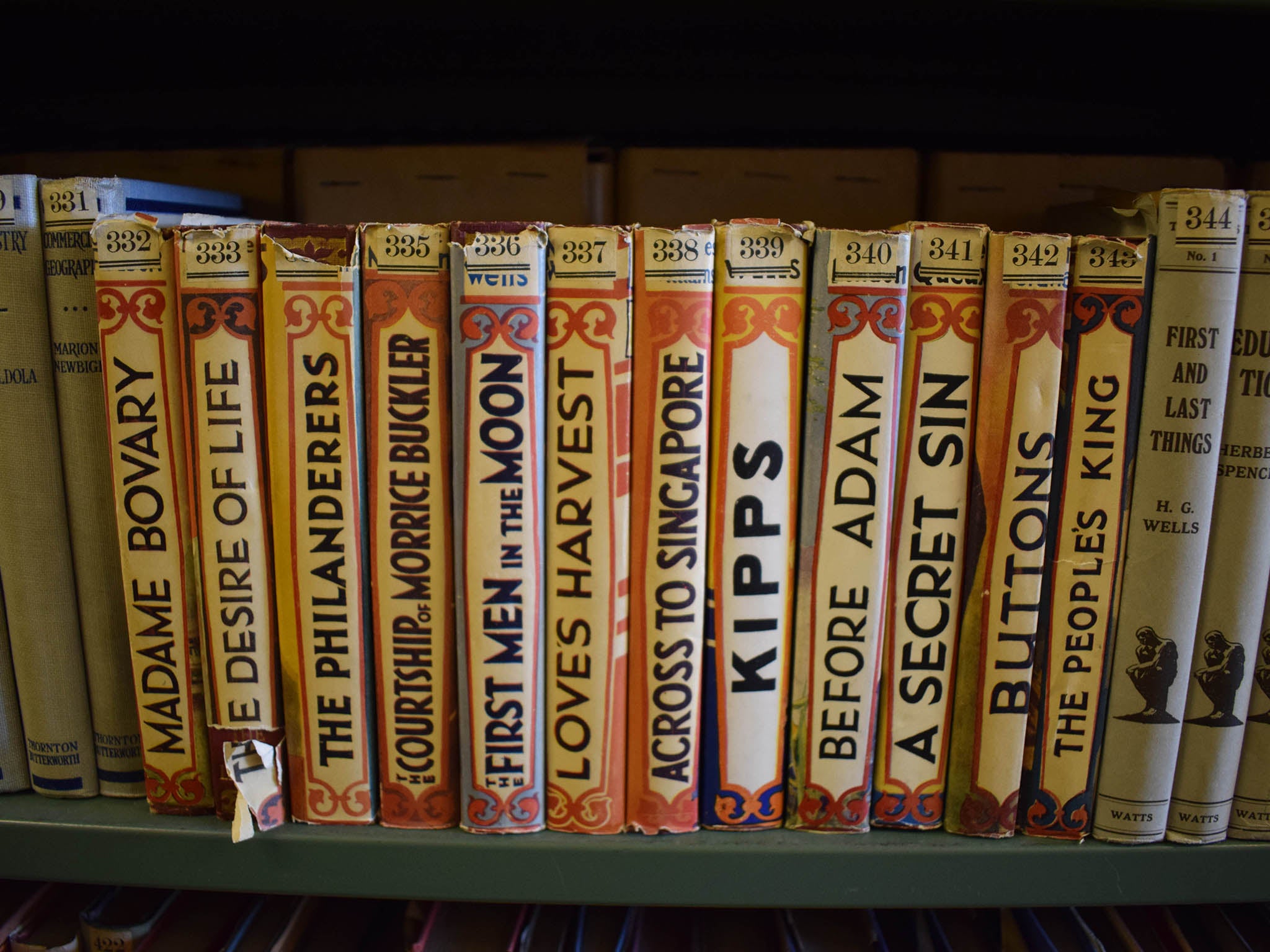

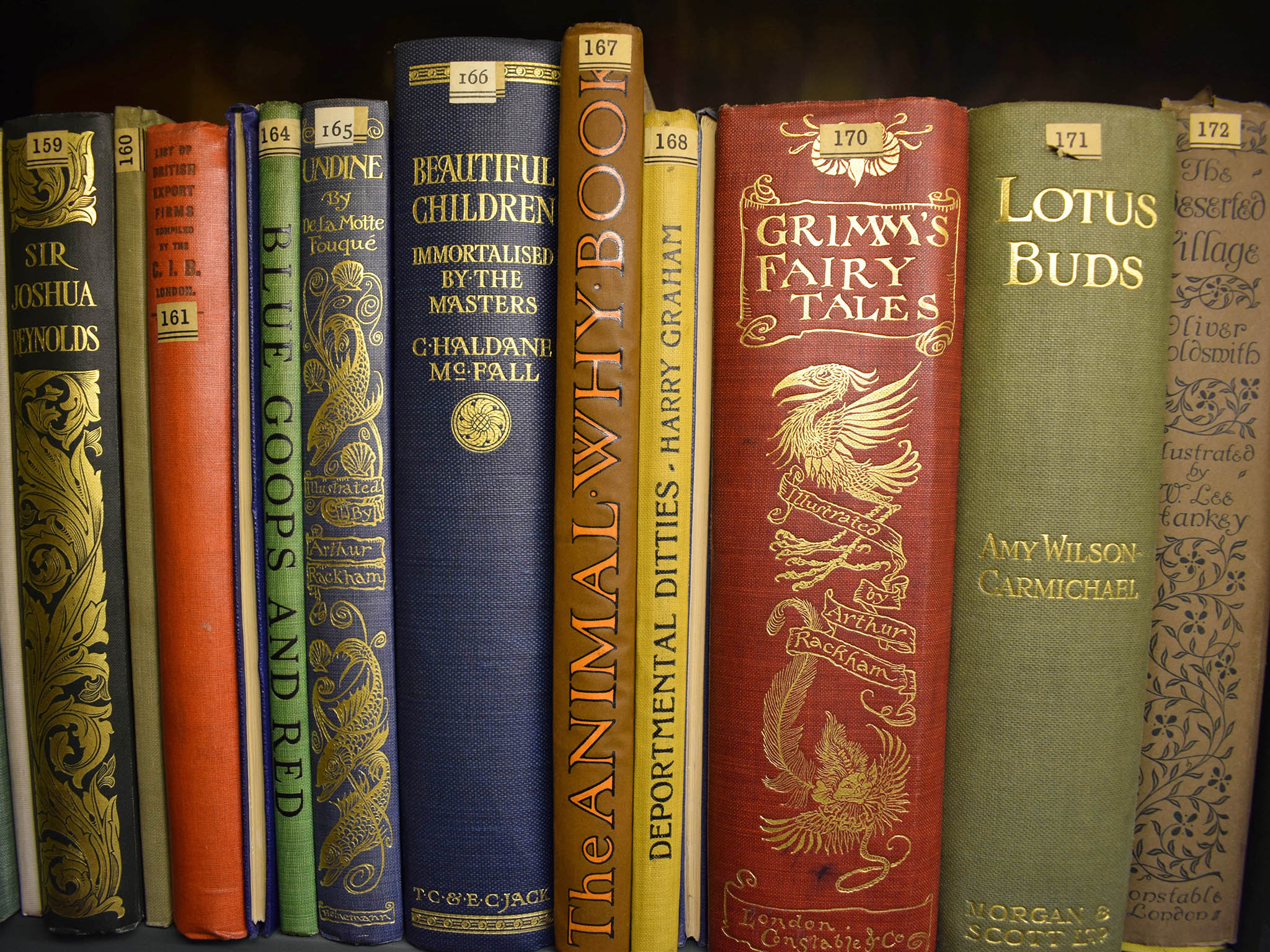

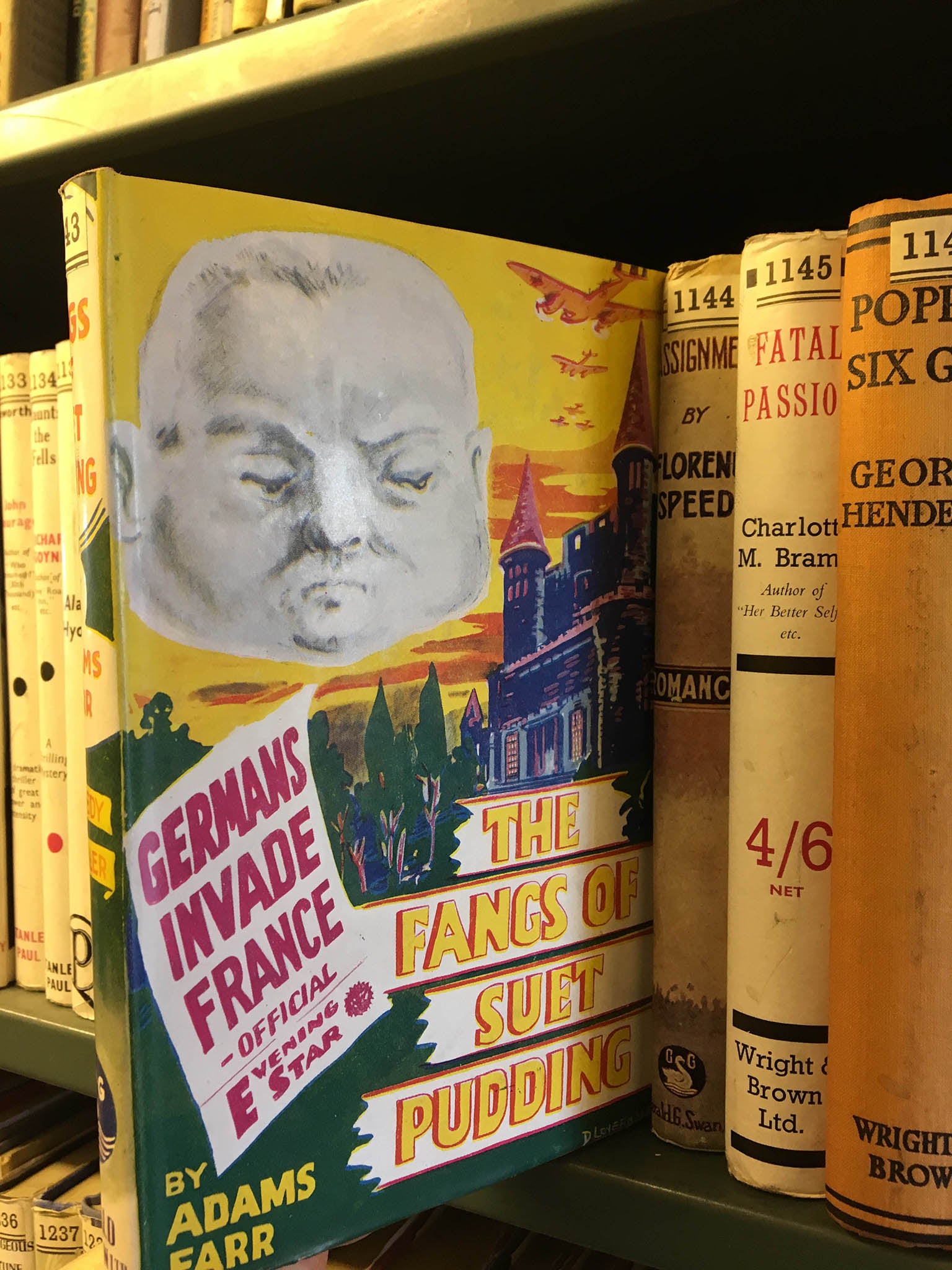

Victorian toys and games jostle for a place with colourful children’s books, Edwardian fiction in pristine dust jackets and popular periodicals. Once considered of “secondary” value to the main academic collections, the tower collection is a treasure trove for today’s readers and researchers.

At the time they were published, librarians would never have considered these books important. Many were ephemeral, populist, mainstream scribblings not worthy of the notice of Cambridge scholars, and so banished to the tower.

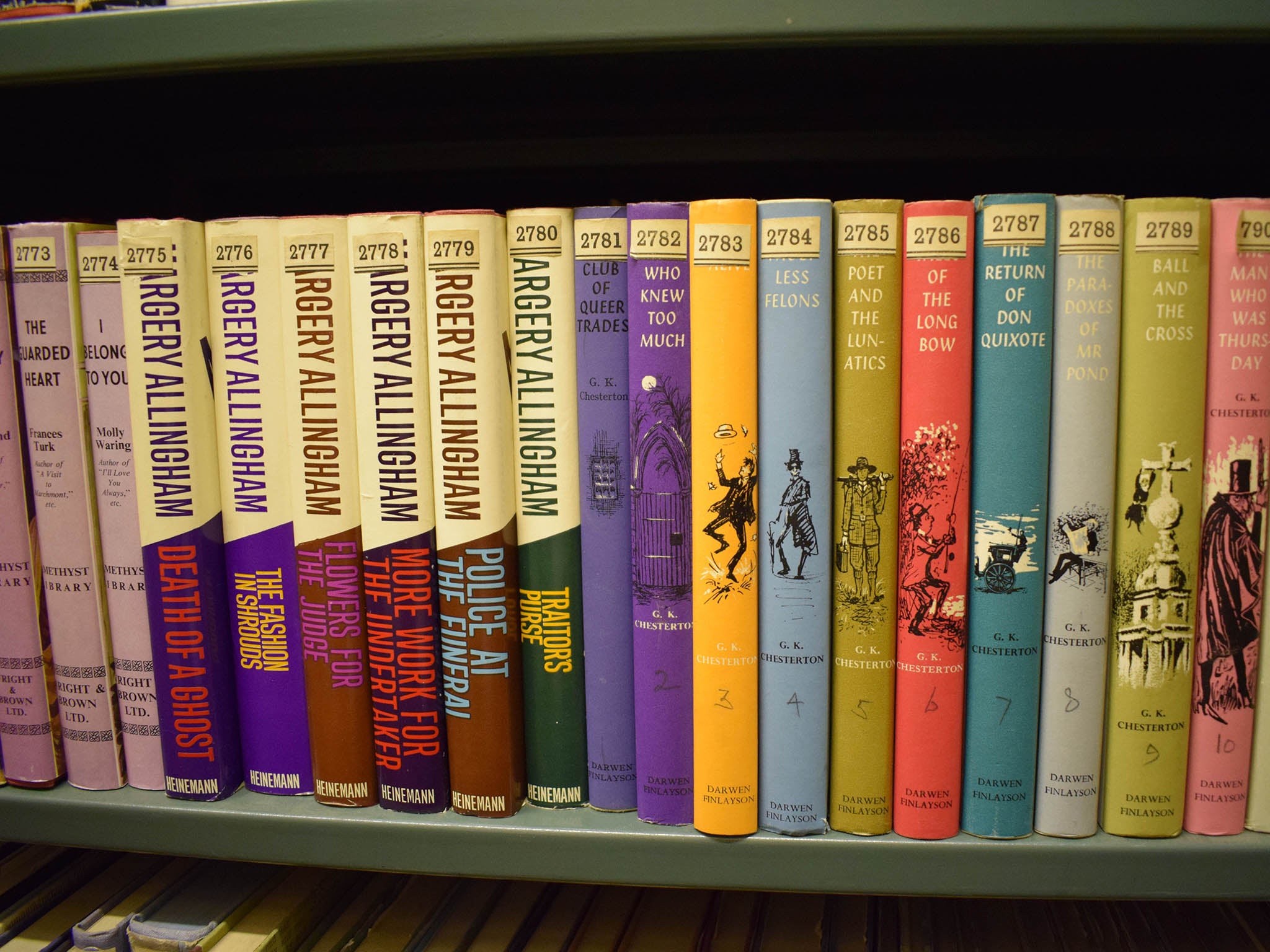

It’s a marker of how little was thought of the books that no thought was given to future browsing by author or subject, and they appear to have been placed in the sequence simply in the order in which they arrived in any one year.

Today, this makes for quite surreal bedfellows with, say, an edition of War and Peace elbowing for position next to a Dull Thud (a long-and-probably-best-forgotten murder mystery). But in terms of social history, it’s fantastic.

You can literally stand in front of a given year and see exactly what was published. This must be the academic equivalent of being a child in a sweet shop; an experience the exhibition tries to recreate for visitors with a towering pillar of 1,950 books with the serious and the quirky side by side.

The benign neglect of these books had other unexpected benefits. It wasn’t until the early 20th century that the potential of the dust jacket (a term that derives from its original role as a purely utilitarian paper wrapper used by 19th-century booksellers to protect ornate leather bindings) as art began to be recognised.

Through the 1920s, the illustrated jacket became established as a vibrant area of the applied arts. Most libraries discarded these paper wrappers on purchase. But Cambridge, opting for efficient minimum handling, did not, a decision we can delight in today.

This probably makes the tower collection unique – unusual even among its peers in the legal deposit libraries of Oxford, Trinity College Dublin, the British Library and the National Libraries of Scotland and Wales.

Looking around the Tall Tales exhibition, the changing fashions through display of book jackets is striking. The Mediterranean colours of Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea, the darker tones of William Golding’s The Pyramid, or the action and adventure of Ian Fleming’s Casino Royale – with artwork by the author himself.

You can’t go up into the university library tower without a trip down memory lane, especially if you, like me, were a bookish child.

I’d forgotten, until I spotted Five Fall into Adventure (1950), my excitement aged seven of devouring all my father’s dog-eared copies of the Famous Five. What a guilty pleasure to see those old friends again in the exhibition.

Perhaps you might not expect to find the original series of the Mr Men in a university library, but aren’t you glad these much-loved characters will still be here in hundreds of years, representing one of the most successful picture books of all time with sales of over 100 million copies in 28 countries worldwide? And to think it all began when Roger Hargreaves’ son asked him what a tickle looked like.

Preserving the documentary heritage, which is what the UK and Ireland copyright libraries do for the nation, is about retaining the breadth of what is published. There is a suspicion that Cambridge’s strength of “secondary” holdings from the mid-19th century onwards came about not so much because of a positive desire to collect (as is now the case) but because it was easier to accept every book than to make decisions on each item.

But there are signs of selectivity on “secondary” periodicals of the period, driven by space, and that selection reflects the taste and social judgements of the time. We have The Girl’s Own Annual (in the exhibition), but not the less respectable Victorian title Tit-Bits, which ran for 80 years from the 1880s. We only started taking the Beano in 1976 (about the time I began waiting for it to drop through the letter box so I could read Dennis the Menace), although it started between the wars; but the Eagle – a more middle-class magazine for children – we have from its first issue in 1950.

The space issue is a serious one. In 2000/01, Cambridge University Library was receiving about 1,600 printed books a week (85,000 per year) and about 1,800 serial parts (newspapers and so on). Even with 17 floors, a growth rate of two miles a year is far from sustainable.

To help meet our responsibility as part of the national collection, we have just opened a brand new book store in nearby Ely. It doesn’t have a tower but it does have more than 100 kilometres of shelves reaching 11 metres high (imagine two giraffes).

Legal deposit also moved into the digital age on 6 April 2013, when new legislation for electronic deposit came into force. Since then, we’ve received a little over 250,000 ebooks on deposit and 270,000 printed books.

There is also now a Non-Print Legal Deposit UK Web Archive, which includes millions of UK websites and surely must be the digital “tower collection” of popular ephemera for the future. Ironically, under the terms of current legislation, this internet treasure trove can only be accessed in the physical reading rooms of the copyright libraries, despite its electronic format.

What, finally, about the Victorian pornography? It has long been a student myth in Cambridge that the library’s tower is where the more risque books are hidden away from prying eyes.

While the exhibition debunks this story, works of a sexual nature do come into the library and for many years were secreted away in a collection that came to be known as the “Arc” (from the Latin for “secret things”).

The Arc used to be stored in the safety of the librarian’s office. Today the remainder of the Arc is in the vaults and the majority of modern additions are books that have been withdrawn from publication for legal reasons, like libel.

And in my office, no more forbidden books but a print of a rare suffragette poster, one of 14 originally shelved in the tower until recently on display in the library to mark 100 years of women’s suffrage. Times do change and, as the second female Cambridge university librarian in 600 years, these symbols do matter.

This year, for the first time, the rainbow flag flew from the iconic library tower to mark LGBT+ history month and show that our city and university are places where people can be themselves without fear of discrimination.

The Cambridge University Library is the work of architect Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, who also gave us the much loved red telephone box (the design of which is mirrored in the library’s tall windows), Battersea Power Station, and the Bankside Power Station (now Tate Modern).

It’s an irony of the exhibition that the tower, home of so many cultural riches, was an afterthought, not in the original plans. Philanthropist John D Rockefeller, who generously provided much of the funding for the building, felt it needed a bold statement to reflect its academic standing.

Tall Tales hopes to make the secrets of the university library welcoming and open to all visitors. The treasures we’re proud to display provide a rare insight to a wealth of ephemeral and popular literature that little survives today outside of the copyright libraries.

The exhibition is a testament to the importance of legal deposit – both print and now electronic – which has been part of English law since 1662, helping to ensure our nation’s publications, and thus intellectual and cultural history, is collected and preserved for all future generations.

Tall Tales: Secrets of the Tower is open until 28 October 2018. Dr Jessica Gardner is Cambridge University’s librarian and director of library services@CamUniLibrarian

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments