‘Oh Baby Baby!’ How Britney Spears survived 20 years of superstardom

Two decades on from her first and biggest hit, Britney Spears remains – despite everything – a remarkable enigma, says Jonathan Liew

The first thing you see is a pair of legs. Then a flash of sunlight, glinting through the windows of a school classroom. Then a foot tapping impatiently against the base of a desk. Then the ticking of a clock. Then the relentless rattle of a pen on a thick, boring book. A wild, weird and wonderful musical journey is about to begin, and precisely two decades on, these final contemplative seconds feel like a countdown: the percussion of a song about to explode into life, and a life about to explode into song.

Britney Spears was just 16 years old when her debut single was first released, and right from the three-note piano motif that begins the track, there’s a violence and a drama to it that both belies her tender years and is utterly consistent with them. Her loneliness isn’t just bugging her, it’s killing her. She doesn’t just want her spurned crush to call her one more time, but to hit her. There’s a vague undercurrent of religious devotion there, too: “I still believe”, “I confess”, “give me a sign”. It is, in many ways, the perfect emblem for the longing of our teenage years, a period of life when everything is trivial and earth-shattering all at once.

The dancing is probably best described as “enthusiastic”. A former point guard for her school basketball team, neither classically trained nor particularly bendy, Britney generally dances with just two main body parts: her arms and her hair. The arms point and whirl and swirl and swipe like she’s trying to fend off the world’s largest swarm of hornets; the hair flips magnificently back and forth and round and round, like a pair of jeans in the washing machine. It’s an athletic, muscular dance: the dance of someone who might not need to dance, but really, really wants to.

“If I have a lot of nervous energy,” she would say a decade later, when the troubles in her personal life were threatening to swallow her whole, “when I start dancing it all goes away. And I just feel emotion.”

Nothing in the song, however, will tell you anything about Britney herself: how old she is, where she’s from, what she’s been through. Over the subsequent two decades, this has been a recurrent theme. These days, there’s a veneer of irony to Britney as a pop star that mirrors our self-referential age. On her official online store, you can buy a pair of wine glasses blazoned with the words “Sip me baby one more time”. Four years ago, when she arrived in Las Vegas to promote her residency there, she was greeted by hundreds of fans wearing her signature schoolgirl outfit from the “…Baby One More Time” video: mid-length skirt, knee-high socks, starchy white school shirt with the tails tied. Occasionally it’s hard to know where the homage ends and the pastiche begins.

And these days, it’s tempting to see Britney as a sort of tribute artist to herself. It’s been 10 years since she had a platinum-selling album, almost 14 since she last had a solo No 1 single in this country. Two decades after its initial release, “…Baby One More Time” is still her biggest seller by miles. It’s sold almost twice as many copies as anything else she ever did. She may have outgrown those early years, but she never outran them.

Back then, though, it was all still raw, fresh, spellbinding, whether you loved it or hated it. On an artistic level, “…Baby One More Time” is credited with changing the course of popular music, steering it out of its introspective, alternative-rock-tinged vibe and ushering in a new age of – as the video’s director Nigel Dick put it – “fun, life, colour, energy and a bit of sex”. On a personal level, Britney became known for wearing her fragilities as a badge of honour, to the point where you could barely still describe them as fragilities (and when you think about it, “…Baby One More Time” is essentially a song about crushing heartache belted out like an empowering girl-power anthem). At its most basic level, though, it was just a girl, not yet a woman, 16 years old, singing and dancing her heart out: a heart full of music and love and impossible dreams.

Something wasn’t right

During the 1980s, the US birth rate rose for the first time since the postwar baby boom. According to the World Bank, the number of children being born per mother rose by around 20 per cent between 1976 and 1990: a generation that as the century drew to a close was growing into fully fledged adolescence. At the same time, technological and economic changes were fuelling an unprecedented boom in the commercial viability of pop music. The CD had definitively usurped the cassette. Americans were spending more of their income on recorded music than at any point in history, before or since. Before long, Napster and Kazaa and Web 2.0 and Apple and Spotify would bring the whole model crashing spectacularly down. But as of the late 1990s, you could scarcely imagine more conducive conditions for cultivating a teen pop phenomenon.

A record producer and former blimp magnate called Lou Pearlman spotted a gap in the market. Two of his boy bands, the Backstreet Boys and NSYNC, were already beginning to gain traction, and so he decided to put together a girl group to complement them. As he scouted around for girls to audition, an acquaintance called Lynn Harless had a suggestion. Harless was the mother of Justin Timberlake, a former Mouseketeer on the Disney Channel’s Mickey Mouse Club who had recently been recruited to NSYNC. And she knew just the girl.

Britney Spears, the daughter of a daycare supervisor and a construction worker from Kentwood, Louisiana, never had her heart set on being a pop star. She’d always seen herself as more of a singer-songwriter, in the vein of Sheryl Crow, Macy Gray or Jill Scott. And her background was in musical theatre, having moved to New York at the age of 10 to appear in an off-Broadway production, only to return with acute homesickness. (Her place, incidentally, was taken by a fellow child star called Natalie Portman.)

But what she really wanted, above all else, was to perform. And having spent two years in Florida working on the Mickey Mouse Club, having accustomed herself to an endless treadmill of singing lessons, dance classes, auditions and filming, she already knew how the business worked. Even at her modest age, Britney was developing the shape-shifting malleability that would make her such a devastating pop star. “Being an entertainer,” she later said, “you long to please people. And become what they want to see.” Or as Chuck Yerger, her principal at Disney would put it: “She had an unshakeable faith that adults would never steer you wrong, and that you should do as you were told.”

In July 1997, Pearlman’s lawyer Larry Rudolph arranged auditions with a number of record labels in New York, accompanied by promo pictures featuring Britney lounging around her back garden in denim hotpants. Mercury and Epic, unimpressed with her demeanour and vocal range, turned her down. But Jive Records – to that point largely known as an R&B and hip hop label – decided to take a punt.

According to John Seabrook’s book The Song Machine, the original intention was to turn Britney into sort of American Robyn: a low-maintenance pop artist who would churn out up-tempo dance-pop hits without fuss. A contract was signed, but there was a catch: Jive could cancel it within 90 days if they decided things weren’t working out. And so, having convinced Britney to ditch her ambitions and embrace life as teen popper, Jive set her up with a gifted but mercurial Swedish songwriter called Max Martin.

Show me how you want it to be

As the story goes, the melody for the song that would end up changing Max Martin’s life forever came to him as he was falling asleep one night. After a while, he decided to haul himself out of bed to commit it to tape. Having been the frontman of a glam metal band in the early 1990s, Martin is said to have an immaculate singing voice of his own, but virtually nobody has ever heard it. He hardly ever gives interviews. In a way, he and Britney were the perfect partnership: a star still searching for her voice, and a voice with absolutely no ambition to be a star.

According to Jive’s A&R man Steve Lunt, who is quoted in Seabrook’s book, Martin originally envisaged “…Baby One More Time” as an R&B song. “Whereas,” Lunt says, “in reality he was writing a Swedish pop song. It was ABBA with a groove, basically. No black artist was going to sing it. But that was the genius of Max Martin. Without being fully aware of it, he’d forged a brilliant sound all his own.” Martin first offered “…Baby One More Time” to TLC and Robyn, who both turned it down. That was the point at which Jive asked him to sit down with Britney in New York.

If you see Jennifer Love Hewitt or Sarah Michelle Gellar kill someone [on TV], do you think that means they go out and do that? Of course not. I don’t want to be part of someone’s Lolita thing. It kind of freaks me out

Recording began at Martin’s studios in Stockholm in early 1998. From an early point, Martin seems to have realised that he had a rare and unusual artist on his hands. It was he who embellished the now-distinctive Britney growl, using a Latin American instrument called a guiro – a sort of notched tube that you rub with a stick to produce a throaty, rasping noise. It’s the sound you can hear on the “I” of “I still believe” in the song’s chorus, and once you hear it for the first time, you can’t stop hearing it in Britney’s work.

At its heart, “…Baby One More Time” is a song about longing. She let him go. She wants him back. It’s a yearning that shakes her with the strength of a thousand thunders, driven on by that tumultuous riff, the subtle (and very Martin-esque) shifts from major to minor that perfectly reflect the unrest of the troubled teenage mind. For all the confected, vaguely titillated outrage that greeted the song’s release, it’s not so much about sex as it is about lust: the deep and painful void you feel when you desire something you can’t have. Nor, despite its evocative pay-off, is it a song about sadomasochism: Martin argues that the “hit me” of the chorus is simply an attempt at euphemism in a language that is not his first. If it’s not entirely innocent, then it’s by no means literal, either: a fairly good rule of thumb to apply to Britney’s career as a whole.

The video was shot over two gruelling days at Venice House School in Los Angeles, the same school where Grease was filmed two decades earlier. The original idea was to film it as a Power Rangers-style cartoon, only for Britney to nix that suggestion on the grounds that the song was being marketed at teens, not tweens. The concept of Britney and her classmates trapped in a stuffy classroom dreaming about boys was one she came up with herself. The school uniforms were hastily sourced from K-Mart, and after a couple of takes Britney found the tails of the shirt were getting in the way of her flailing arms. And so, as it turned out, the bare midriffs that so scandalised the snowflakes of Middle America occurred largely by happenstance.

It’s important to note how much of Britney’s early success was driven by her own imagination. After all, who was going to have a better handle on the whims and tastes of the teenage market than one of their very own? What’s particularly striking, from reading the accounts of how Britney’s career came together, is just how clear her vision of it was. She knew what she wanted to look like, she knew what she wanted to sound like, she knew how she wanted to come across. Trouble was, others often had a different opinion. And over the subsequent months and years Britney would discover what happens when an ambitious young pop star collides head-on with the images and expectations projected onto her.

It’s not the way I planned it

Jive was delighted with the results. Convinced it had a massive hit on its hands, it started mapping out a launch strategy. In the summer of 1998, Britney went on a nationwide publicity tour, performing the song in shopping malls up and down the country. Two months after its initial release, “…Baby One More Time” hit No 1 in the Billboard charts, a feat it would match in virtually every country it was sold in.

It hit the UK in February 1999, entering the charts in the same week as “Runaway” by The Corrs, “Ex-Factor” by Lauryn Hill and “Sunburn” by Michelle Collins off Eastenders. It ended the year as the biggest-selling song of the year, shifting 1.4 million copies. By which time the Britney phenomenon had begun in earnest; powered by the whiff of novelty, a pinpoint marketing campaign, Britney’s own tireless toil and a sexually charged fascination that was only vaguely her own.

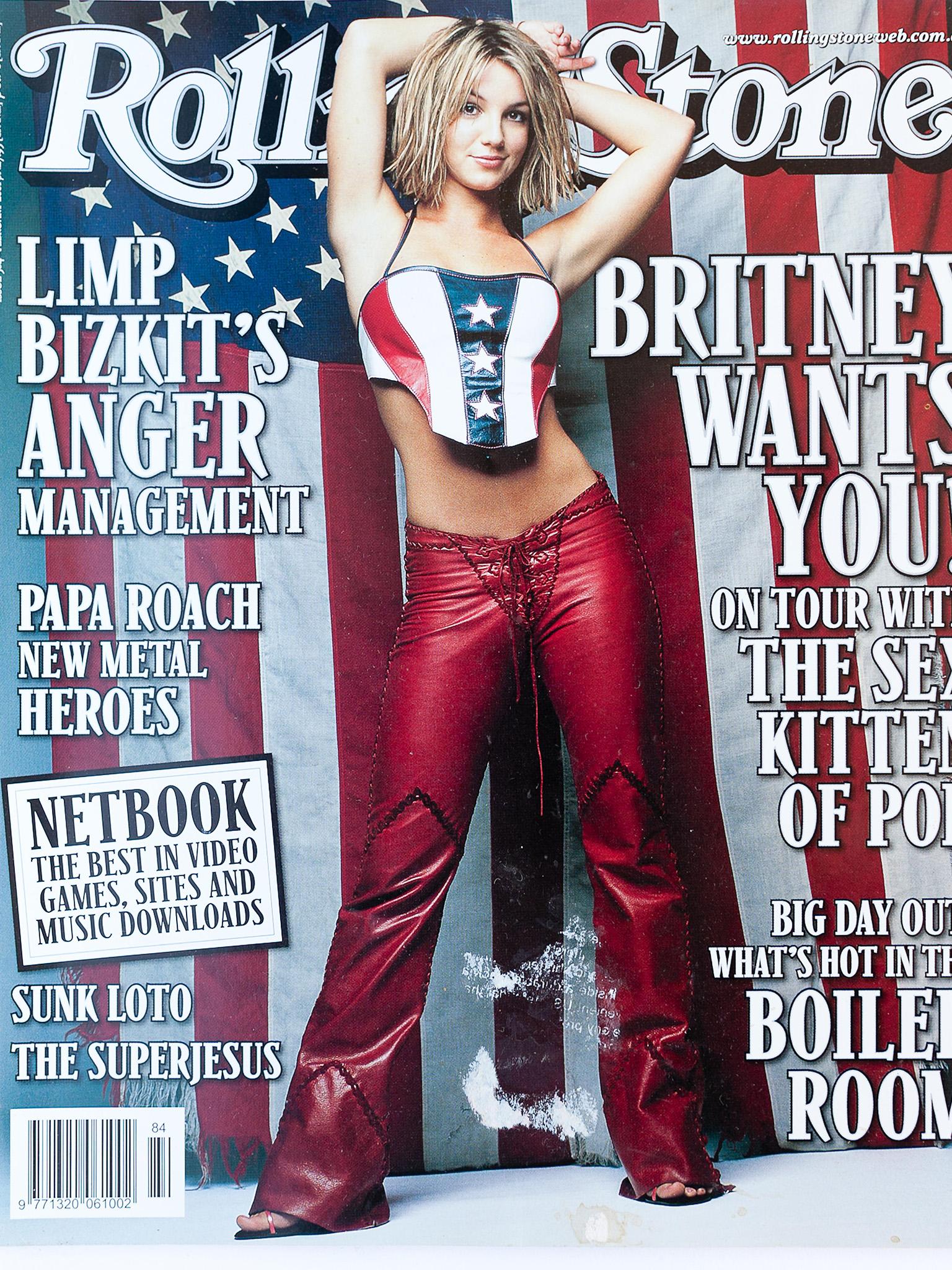

By way of example, read the way Britney was described in a now famous Rolling Stone profile in March 1999: “Britney Spears extends a honeyed thigh across the length of the sofa, keeping one foot on the floor as she does so... The logo of Spears’ pink T-shirt is distended by her ample chest, and her silky white shorts – with dark blue piping – cling snugly to her hips. She cocks her head and smiles receptively.” Later in the article, the phrase “bubblegum jailbait” makes an appearance.

This was, lest we forget, a 17-year-old child being described here. Was this as creepily weird in 1999 as it now feels in 2018? Either way, Britney herself initially tried to play down the significance of the risqué photoshoots and sexualised imagery that a voracious media were all too keen to foist upon her. “It’s like on TV, if you see Jennifer Love Hewitt or Sarah Michelle Gellar kill someone, do you think that means they go out and do that?” she argued. “Of course not. I don’t want to be part of someone’s Lolita thing. It kind of freaks me out.”

From the very moment she emerged, then, Britney was conceived in terms of her sexuality. An innocent comment in an interview about wanting to preserve her virginity until marriage was lecherously discussed and probed for years afterwards. You could argue about the extent of her own agency here, the extent to which she was an unwitting or even an unwilling participant in her own lascivious myth-making. But only dictators ever get full, unmediated control over their public image. And what is incontrovertible is that no American pop star had ever been discussed in these terms, this widely, at this young an age. Nobody can really imagine what fame will feel like until it smacks them in the face. And for the major protagonists in “…Baby One More Time”, the rollercoaster ride that they were about to go on would throw them all in wildly different directions.

Max Martin thrived, going on to become one of the world’s greatest and most prolific pop songwriters. Whether it’s The Weeknd’s “Can’t Feel My Face”, Katy Perry’s “I Kissed A Girl” or Taylor Swift’s “Blank Space”, chances are you’ve danced to one of his hits at some point in the last two decades. Rudolph, the man who introduced Britney to Jive, survived, remaining Britney’s manager to this day. Pearlman, ever on the lookout for a quick buck, died in a Florida jail in 2016, having ended his career in disgrace after being found guilty of running a massive Ponzi scheme.

There’s a world-weariness to her these days. She’s seen it all, and yet she’s still going. And over two decades, she’s performed a rather neat trick: she’s gone from star to anti-star, the insider who became the outsider, the ultimate product of the pop machine who became its most high-profile victim

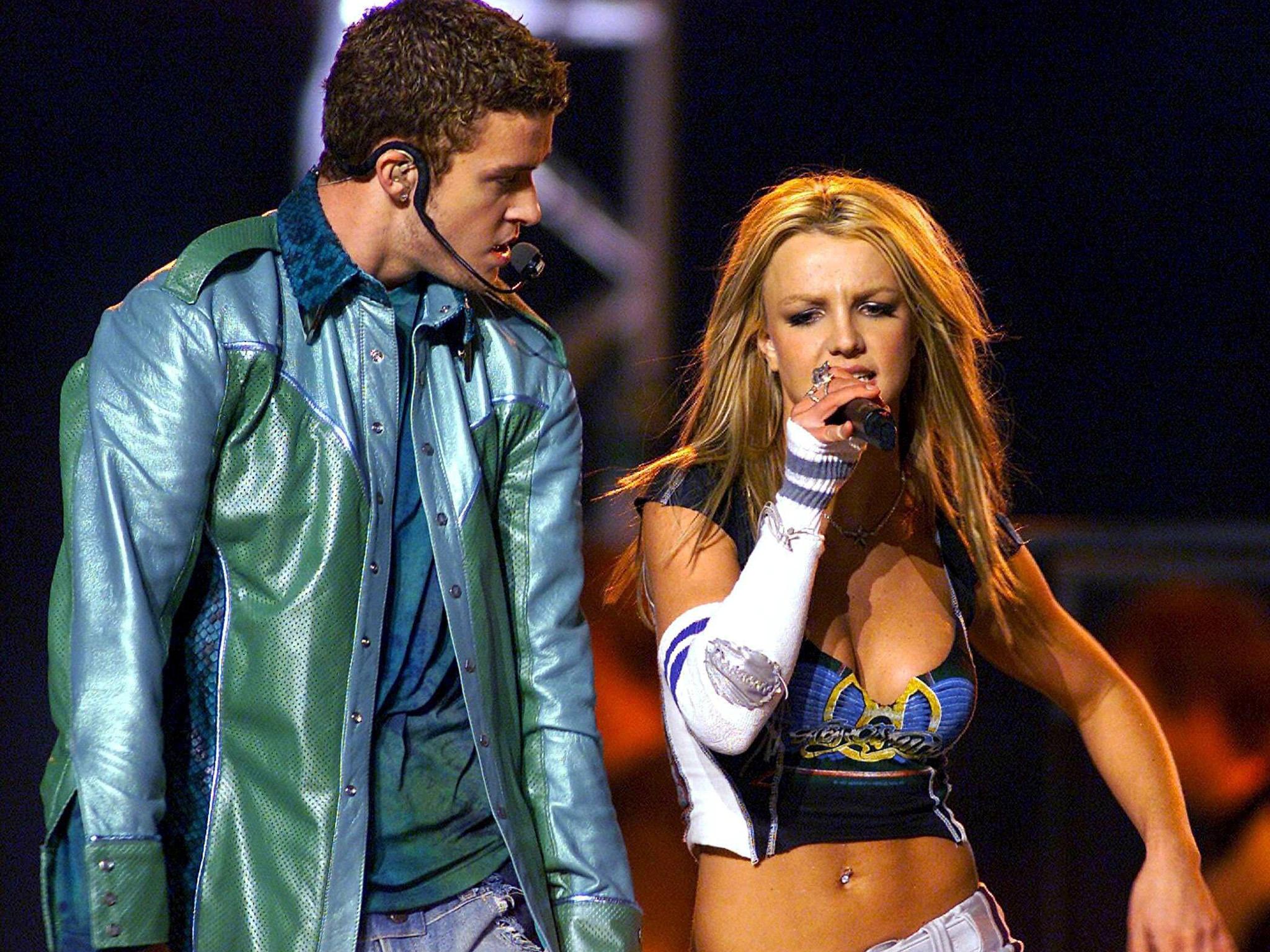

Britney, on the other hand, did a little of all three. Powered by the momentum of her debut single, a torrid touring schedule and a string of bona fide hits – the epic “Oops! I Did It Again”, the sweaty “I’m A Slave 4 U”, the peerless “Toxic” – she quickly became the biggest pop star on the planet. Over time, though, the cruel treadmill of celebrity began to take its toll. A turbulent, publicly scavenged personal life saw the breakdown of a tempestuous relationship with Timberlake, a short-lived marriage to a childhood friend called Jason Alexander, and another wedding in 2004 to one of her dancers, Kevin Federline, in which the groom and his party all wore matching white tracksuits with the word “Pimp” on the back.

That, remarkably, was not the low point. The specifics of her much-publicised mental breakdown in 2007 remain shrouded in mystery, but what we saw with our own eyes – the shaved head, the real-time panic, the glazed glare – was harrowing enough. Britney is still dealing with the legacy of that episode: as a result of decisions taken on psychiatric advice more than a decade ago, she remains unable to make key personal or financial decisions without the approval of her father and her lawyer. Troubled male artists are often given the license to “own” their personal turmoil for artistic benefit. Britney wasn’t even allowed to own her bank account.

But as the popular meme reminds us, Britney survived 2007. She’s managed to raise two children. She’s performed an extremely lucrative Vegas residency, with another scheduled for 2019. And quietly, she’s been putting out some of the best music of her career. But at the same time, as the harsh glare of pop superstardom has shifted onto other, newer acts, she seems to have receded from view somewhat: upending the traditional relationship between performer and audience by becoming over time not more accessible, more familiar, more tangible, but less. Two decades into her career, can we really say we know Britney Spears at all?

Give me a sign

Tucker Carlson: You’re going to be on the National Mall soon, performing for Pepsi and the NFL, and also to support our troops. A lot of entertainers have come out against the war in Iraq. Have you?

Britney Spears: Honestly, I think we should just trust our president in every decision he makes and should just support that, you know, and be faithful in what happens.

Carlson: Do you trust this president?

Spears: Yes, I do.

Carlson: Excellent. Do you think he’s going to win again?

Spears: I don’t know. I don’t know that.

(Interview on CNN, September 2003)

At times, she’s been painted as the unwitting emblem of Bush-era conservatism, at others as the teenage rebel who kicked out at the machine, only to get kicked back harder. Neither mask really seems to fit her

In August this year, Britney brought her Piece Of Me tour to the rather incongruous surrounds of the Open Air Theatre in Scarborough. As she lip-synched her debut hit to a soaked but ecstatic North Yorkshire crowd, she seemed strangely dislocated. The crisp chords and urgent beat of “…Baby One More Time” had been reimagined as a sort of Gothic piano ballad, accompanied by dancers bearing giant bat wings. The killer riff had been excised, along with most of the percussion. Ever the professional, she flailed her arms around and whipped her hair, just like she knows how. But as the song segued without ceremony into an “Oops! I Did It Again” medley, it was legitimate to wonder: is she still a performer, or simply a vessel for a performance that was conceived, devised and choreographed long ago?

There’s a world-weariness to her these days. She’s seen it all, and yet she’s still going. And over two decades, she’s performed a rather neat trick: she’s gone from star to anti-star, the insider who became the outsider, the ultimate product of the pop machine who became its most high-profile victim (which may also explain why she has become a supremely popular gay icon).

And yet virtually none of this ever seems to impinge on her actual music. With the exception of “Piece Of Me” – a cartoonish, tongue-in-cheek rant at the tabloid media – Britney doesn’t use pop as her pulpit, as a means of settling scores or articulating a world view. In an age where being a prominent female in music often entails being the leader of a cause as well, in an age where even Taylor Swift feels compelled to nail her blue colours to the mast, Britney simply carries on doing what she’s always done: churning out danceable bangers to a loyal and fervid fanbase.

Her total resistance to politics now feels refreshingly anomalous, almost oldschool. In the hours after Donald Trump’s inauguration, some of the world’s leading pop stars – Rihanna, Drake, Miley Cyrus, Adele – posted pictures of Barack Obama on social media in solidarity with the outgoing president. Around the same time, Britney posted a picture of a small dog with a fluffy brown coat, accompanied by the caption: “How I feel when I wash my hair”.

At times, she’s been painted as the unwitting emblem of Bush-era conservatism, at others as the teenage rebel who kicked out at the machine, only to get kicked back harder. Neither mask really seems to fit her. Did she own her sexuality or was she owned by it? Was she a feminist icon or a post-feminist sap? Was she imprisoned by the male gaze, or was there something empowering, even subversive, in the way she turned it back in on itself?

These are all relevant questions, and they may to a large extent still determine how you feel about her. But at this point in Britney’s career, it begins to feel a little like a pointless escapade, an exercise in intellectualising an artist who at no stage in her career has ever demanded that we intellectualise her. Perhaps, two decades in, all we can really say for sure is that “…Baby One More Time” is one hell of a tune.

Earlier this year, one die-hard Britney fan, trying to explain his obsession in Time Out magazine, provided perhaps the best and most succinct defence of Britney yet offered. “She’s a human respite from 2018,” he said, and perhaps – all saccharine triteness aside – there’s something to that. Her teenage exuberance may be well behind her. She may have been through a world of pain. She might never recapture the thrilling momentum or boundless optimism of those early years in the business. And she never really was that good a dancer, when you think about it. But at least, after two decades of turmoil and turbulence, she’s endured: still here, still resolutely Britney.

Maybe the reason it feels so natural to refer to her on first-name terms is that for all her opaque mystery, in many ways she remains wholly relatable to anyone who’s felt pressure to look and act a certain way. Who’s ever tried to balance the urge to please with the urge to walk your own path. Who’s ever felt judged, trapped in a web of everyone else’s expectations. Who’s ever felt like they’re being measured against an impossible standard: expected to be attractive and yet homely, rich yet humble, an embodiment of family and an embodiment of fantasy.

And then, there are the parts we can barely envision. Being chased through your hometown by photographers on motorbikes. Sensing stalkers outside your bedroom window. Watching associates and ex-boyfriends disclose your most intimate secrets for money. Being asked multiple times, in public, on camera, by complete strangers, whether you’ve lost your virginity yet. Seeing your childhood dream refracted through a million creepy male lenses. Perhaps, on reflection, the real miracle is how she’s managed to keep the show going for so long.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments