Herefordshire: The pastoral idyll conceals a county riven by Brexit

With few jobs for young people, poor roads and its agricultural core put at risk by Brexit, why did so many farmers in Herefordshire vote Leave? Patrick Cockburn sounds out the locals

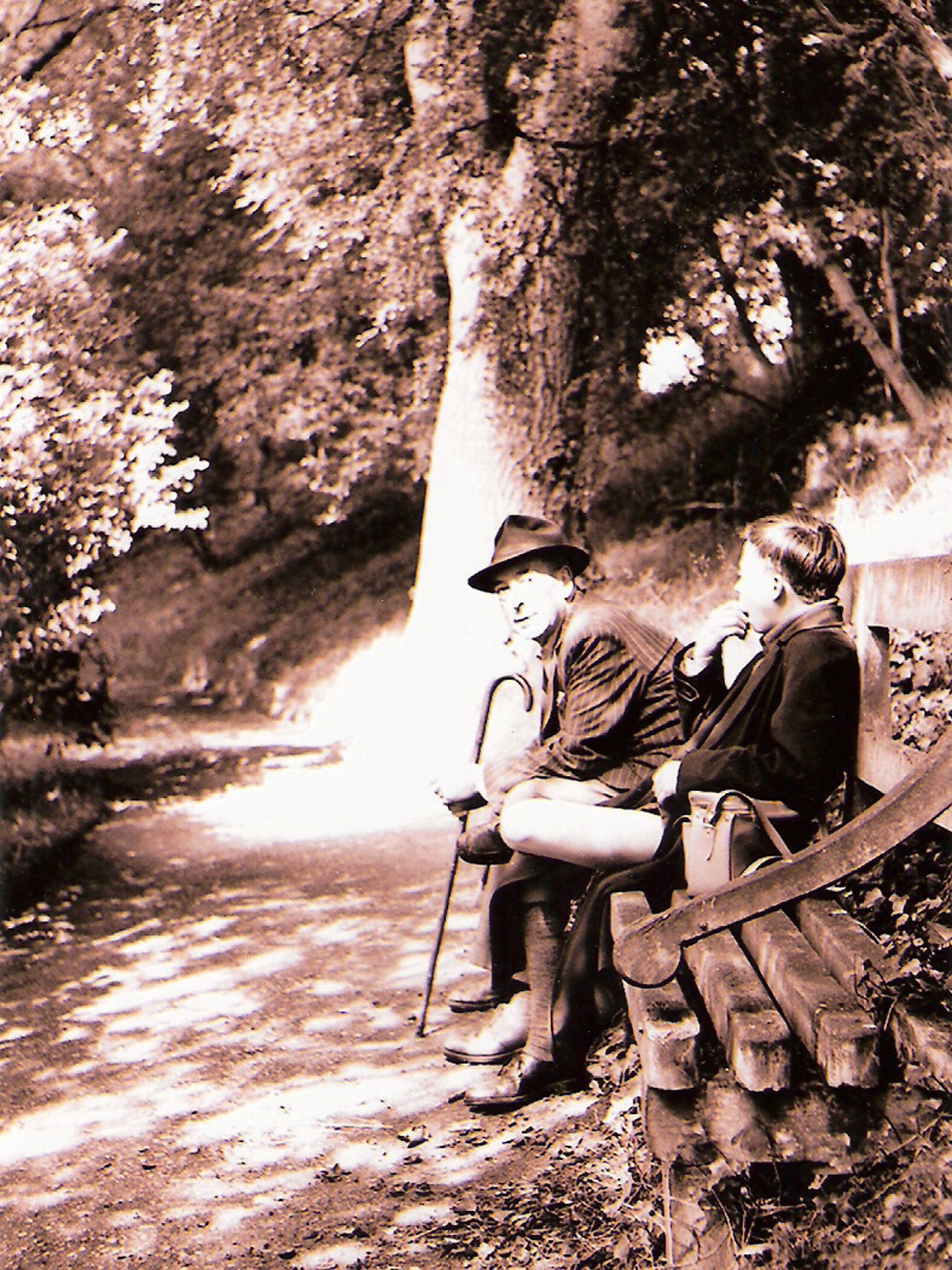

Herefordshire, a county of apple blossom and wild daffodils overlooked by the dark Welsh hills, is England’s arcadia. Its landscape inspired the magical land of Narnia according to CS Lewis. Its ancient gnarled oaks were the reputed model for the Ents, the fabulous trees that walk through the woods and talk to hobbits and wizards in JRR Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings.

For anybody in search of an idyllic pastoral England, Herefordshire appears to be the right place to come. Everything is on a human scale, from the small cathedral city of Hereford with a population of 70,000, to the scattering of towns, villages, and hamlets filled with black-and-white timber frame houses. For those seeking signs of a more robust England, recalling heroic battlefields from Agincourt to Arnhem, there is the comforting presence of the SAS headquarters on the outskirts of Hereford.

Many people living here do not relish change for understandable reasons and regret the changes in Britain since the country entered the EU a half century ago. “There is a lot of nostalgia in Herefordshire,” says local historian David Whitehead. He notes that local newspapers like to run two-page spreads of old photographs of the county in the inter-war period when life appeared to be more stable and predictable. “People feel closer to the past here than in most of England,” he says.

A feeling that Britain should not abandon a successful tradition of standing on its own is particularly strong in this county, which voted to leave the EU by 59 to 41 per cent in the referendum of 2016, a result which was confirmed by the outcome of the EU parliamentary election on 24 May.

As in the rest of Britain, the pro-Brexit voters are a broad coalition of different and often contradictory interests, held together by a conviction that the EU is the cause of their troubles. The grouping includes well-off farmers, fed up with bureaucracy but happy to receive substantial subsidies, retirees in bucolic villages, and those “left behind” or “left out” for whom Britain’s EU years have brought insecure ill-paying jobs, housing too expensive to buy, and a flood of immigrants.

The beauty and tranquillity of Herefordshire are deceptive: polarisation over Brexit is as deep here as in Islington or Sunderland. Dr Nick Meyer, a retired GP in Ledbury in the east of the county, replied to a question about political divisions by saying he was planning on the following weekend to go on a boat trip with four friends, three of whom, including himself, were staunch Remainers and the fourth a committed Leave supporters. The Remainers had wondered if they should leave their friend behind to avoid rancorous disputes, but had finally decided to include him in the hope that they might change his mind during the sailing trip.

“Brexit is very destructive in the way it has created a divided Britain,” says Dr Meyer. “Feeling about it is much stronger than it is between those supporting different political parties.”

The level of anxiety over Brexit is no less than in metropolitan Britain. Tom Tibbets, who two years ago started a craft cider making business, says that he suffers acutely from Brexit related worries. “I have stress-related alopecia, which means that my hair is falling out,” he says, leaning forward to show a depleted but still substantial mop of dark hair. “According to my doctor this is all stress related.”

Herefordshire is more “feudal” than neighbouring counties and Whitehead says that many big landowners “are the same as a hundred years ago”. He says that much of the land between Ross-on-Wye in the south and Hereford in the north belongs to the Duchy of Cornwall, a purchase they made in the 1950s.

Overall, however, Herefordshire is an impoverished county with few jobs for young people, who go elsewhere for work, while well-off professionals from London and Birmingham buy local houses for half the price they would pay at home. “It is an underdeveloped county with poor roads, social services, buses and schools,” says Dr Meyer, who has worked in Herefordshire as a doctor for 30 years.

In Herefordshire, as in the rest of Britain, it is easy to discover the reasons why people want Britain to stay in the EU: they make concrete arguments about the economically disastrous consequences of leaving. But Brexiters have a different set of priorities revolving around the supposed threat to Britain’s independence as a nation state by power-hungry bureaucrats in Brussels and other continental capitals. This argument is buttressed by compelling if dubious claims that the EU has for years been bleeding Britain financially and, once out, we will get the money back.

John Forsyth is one of many former SAS soldiers who has stayed in Herefordshire and works as a health and safety consultant. He says he voted as a young soldier in the 1975 referendum in favour of membership of the Common Market, but he was dismayed to find that “it has evolved towards a state of Europe”. He sees the EU as corrupt, incompetent and undemocratic: “The reason I want to leave is that I see the EU as this inflexible bureaucratic monstrosity. We would do better to look after our own interests and be able to change our own laws.” He believes that that the referendum did lead to an upsurge in racism, to which he is much opposed, and agrees that Britain has been politically polarised by Brexit, though he believes this will disappear in time.

He does not use the word ‘self-determination’ but his views are very similar to those of nationalists the world over, from the American fighting for independence in the 18th century to the Irish and Indians in the 20th. In all cases, there was a natural desire by people to control their own lives and a tendency to blame all their ills on the British government. Many of the criticisms were justified but scapegoating contains hidden dangers, whether the target is London or Brussels, because it means that those seeking to break free from a detested central authority do not have to devise practical policies of their own.

Even so, it is strange to hear farmers in Herefordshire say they voted to leave the EU when they have benefited immensely from its subsidies. “The county voted massively for Brexit, but the people who are going to lose from Brexit are the farmers,” says James Marsden, an environmentalist who formerly worked for the Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra). The most important of these is “the basic payment scheme of £205 per hectare, which is paid not on what you do, but on how much land you own.” He says that outside the EU the smaller farmers will inevitably go the wall unless, as the Defra minister Michael Gove proposed last year, subsidies are in future geared to farmers cultivating the land in an environmentally friendly way.

For now the reverse is happening: Marsden pointed through the windows of the house where we were talking at the pretty-looking cider apple orchard where the uniform rows of bush-sized trees were in full bloom. “What we are looking at,” he said, “is an intensely managed monoculture: the trees are not managed by hand but by machinery; they are sprayed four times a year; there are herbicidal patches beneath the trees. From the point of view of diversity, you might as well be growing rape seed or grain.”

Overall, Brexit will have two contradictory consequences for the rural environment: it will help preserve it because there will be fewer farmers, but will also damage it because those who stay in business – the larger ones with more capital to buy new machinery - will exploit it more intensively unless they are tightly regulated. He says small hill farmers in Wales, where he works part of the time, are highly conscious that they are facing extinction post-Brexit, but “in my parish in Herefordshire, they are still in denial”.

Some are, in fact, deeply worried about their future. Owen Whittall farms cattle, sheep and mixed crops on 800 acres and is conflicted about Brexit. “I remember the morning of the referendum. My wife voted ‘in’ and I voted ‘out’ and I was not a happy person. I felt very uneasy with my decision and I am still not happy.”

He explains that he voted as he did because “I was becoming very unhappy that Europe was a bottomless pit and the pit was becoming deeper [in the sense that it was more autocratic, bureaucratic and expensive]”. Asked why so many of his fellow farmers had voted to leave, he says that “a lot had just read the sign on the side of the bus and thought ‘let’s get out and we’ll have £10bn to ourselves’, which was naive”.

He thinks that many of the smaller farmers will not survive outside the EU unless they get a second job, intensify their farming, or accept a lower standard of living. He says with some scorn that a lot of well-paid professional people from the cities will be “buying idyllic little farms with a few Hereford and Dexter cattle and doing the lifestyle thing”.

Dr Meyer, the Ledbury GP, says: “It will be disastrous for the farming community, but most farmers I know were for Brexit.” He says that one important reason for this was the EU’s bureaucratic hoops that even fervent Remainers confirm are fearsomely difficult. Tom Tibbets, the cider-maker who campaigned against Brexit, says he knows from personal experience that even moving a pig to the abattoir for personal consumption requires endless time-consuming paperwork. On the other hand, once these bureaucratic hurdles are negotiated, the flat rate subsidy is paid without further effort. Farmers do not volunteer what they get but one, on a medium-sized farm, said they were getting £30,000 a year.

This is all very different from Narnia. Julian Whitmarsh, who owns the “Jules” restaurant’ in the picture post card village of Weobley, has a caustic take on social developments in rural Herefordshire. “Agriculture has ceased to be a craft and has become an industry,” he says. “It employs fewer and fewer people because the big farms that once employed eight workers now employ one.” He complains that villages are full of people who have sold their houses in the cities and “put on green wellies and are playing at Ambridge” (the fictional village in The Archers, the long-running BBC radio soap opera on rural life).

His explanation as to why so many people in Herefordshire voted against their own best interests is that they are instinctively right wing and badly informed. Then there are the newspapers on which they rely for information about the EU and everything else in the world. He says: “The Daily Mail sells 50 copies every morning in Weobley and The Daily Telegraph almost as many copies. while there are about five who buy The Guardian and quite a few of us buy the i.” The strong Liberal Democrat and Green vote in the European parliamentary election in Herefordshire does not quite confirm this picture of right wing domination, but it sounds broadly correct.

Not all agriculture is industrialised. Cider apples can be shaken loose and hoovered up by machine, but not eating apples, blue berries or strawberries which must be picked by hand. Workers are still needed to do the dirty jobs in the poultry units that are springing up all over the county. Such jobs have been done hitherto by a great influx of foreign labour from Eastern Europe who not only work as pickers or pruners but as vets in the abattoirs and managers in the hotels. Farmers say that this labour force, on which they depend, is in increasingly short supply because of fears of Brexit, the low value of the pound and improved economies in Poland, Hungry and elsewhere.

Esther Rudge, a fourth generation farmer, worries about whether or not she will be able to go on getting the 30 foreign labourers, mostly Poles, whom she has formerly employed to pick her eating apples. Others face greater problems which they may be slow to appreciate: she and her husband have friends “who employ 1,000 foreign workers but still voted Leave”.

An even greater threat facing British farming is the prospect that, after a no-deal Brexit, a British government might be desperate for a trade deal with the United States. The price for this might be the opening up of the British market to cheap American farm produce. “Agriculture could be the sacrificial lamb,” Rudge believes, “so you would get cheap beef and chicken coming into the country.” Even without such a deal, she fears that a British crash out of the EU leading to trade on WTO rules would ruin the British livestock industry.

Some commentators have compared the prospects for British farming after Brexit as being like playing Russian roulette, but with only one chamber of the revolver unloaded. Others, with long experience of farming in the region, have a less cataclysmic but still gloomy view of the prospects for farmers. Francis Chester-Master, a landowner and land agent, gives a summary of the prospects with or without Brexit.

“Most farmers and landowners who I work for are expecting the gradual removal of direct farming subsidies. This will reduce farming incomes and probably agricultural rents over time. Inevitably, this will mean in the short term (possibly the medium term) that there will be less money in the agricultural regions of the UK. This won’t just affect farmers and landowners but also the local economy which, particularly in rural Wales and other more remote areas of the UK, is heavily reliant on the farmers and landowners.”

Chester-Master says that what is most damaging for rural Britain is the continued uncertainty over whether or not Britain will leave the EU. But this uncertainty may not be a temporary problem supposing Brexit occurs. Rudge, who runs a successful medium-sized farm, says that outside the EU Britain “will be a small fish in a large pool” and small fish necessarily live day to day at the mercy of forces they do not control. Old certainties are evaporating and nobody can predict what will take their place. The farmers of Hereford – and in the rest of Britain – have deepened the uncertainties they were seeking to escape.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments