The Tory vision for a post-Brexit economy is a dead-end – but there is an alternative

Effective industrial strategy requires a clear understanding of Britain’s place in the world economy now, and a clear set of goals for where we want it to be in the future

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Last week’s resignations of Brexit big beasts David Davis and Boris Johnson demonstrates once again that the customs union is the beating heart of the Tory Brexit breach. The nature of our future trading relationship with the European Union straddles so many Tory totems from the role of business to the European Court of Justice to the border with Ireland. As a consequence an internal party “deal” that took two years to put together fell apart within two days and now we are once more the laughing stock of Europe with only a matter of months before we leave.

Reforging 40 years of economic, political and societal links in a constructive, inclusive and forward-looking way would be a challenge for any government but is clearly far beyond the capacity of this one. As a government in waiting, it is Labour’s job not only to hold the government to account but to set out what our approach would be. This is the work that Keir Starmer and Labour’s Brexit team has undertaken, exemplified by the amendments our party tabled to the Great Repeal Bill. But it is also my job as shadow minister for industrial strategy to consider what Brexit means for our economic future and to place decisions in that context. And that has to mean an economic future that includes everyone, and does not merely carry over the regional and social divides that helped deliver the referendum result in the first place.

To achieve this we need to look back even as we look forward. And to look outwards to the world even as we consider how best to maintain a close relationship with the European Union.

The industrial landscape of Britain today is the product of a succession of industrial strategies or non-strategies, each of which was ultimately unable to deal with the reality of the larger world economy. Britain entered the 20th century hoping to maintain its position as the supplier of manufactured goods to the largest empire the world had ever known, a strategy that could not be sustained given the scale of US industry and the understandable desire of the rest of the Empire to build its own industrial base. By the 1960s, British industry was increasingly focused on our domestic market, but even that more limited “strategy” proved untenable in the face of more efficient and larger scale foreign competition from the United States, Japan, Germany, Korea and ultimately China.

In response, the Tories under Margaret Thatcher and her successors, and to a lesser extent the 1997 Labour government, pursued a kind of “anti-industrial strategy”. This substituted first North Sea oil and then City of London financial services for industrial competitiveness. North Sea oil was a finite national asset that delivered the expected temporary economic boost. The impact of our burgeoning financial sector was more complex. It brought substantial benefits in jobs, revenues and social capital, particularly to London. It also drove the “financialisation” of our economy.

Financialisation – the anti-industrial strategy

The way in which financialisation proved to be an anti-industrial strategy is admirably set out in leading economist Mariana Mazzucato’s new book The Value of Everything. In it she describes the “two faces of financialisation”.

The first of these is the way in which the financial sector has stopped resourcing the real economy – instead of investing in companies that produce “stuff”, finance is financing finance. Why lend money to a manufacturer that may fail when you can make a bet on some options hedged with other options that virtually guarantee a return in a few weeks? The owner of a medium-sized manufacturing business gave me a striking example of this recently. His high-street bank was initially supportive when he requested a loan for new manufacturing equipment, which would significantly boost productivity. Once the bank realised that the equipment would not be something they could sell on should he go bankrupt, their interest drained away entirely. It was willing to lend based on liquidation value, but was not willing to take a risk on a living business. In a financialised economy, capital tends to flow towards standardised securities rather than actual operating businesses that present bespoke risks.

But it is not only financial capital that is diverted from the real economy. Human capital is sucked in too. When I graduated from Imperial College in 1987, I would estimate that only about 10 per cent of my electrical engineering cohort went into industry. The majority went into management consultancy and finance, which paid better as well as having clearer career paths. Recently the dean of an engineering department told me that was still the case and asked how I could expect engineers to go into engineering when finance paid so much better and was quite honestly the only way a graduate engineer could ever hope to buy a home in London.

I responded that they should come to Newcastle where not only could they buy a lovely home on an engineer’s salary, but also be within a few minutes of some of the most beautiful countryside in the world and at the heart of a concentration of culture that rivals far bigger cities. I recognise the dean’s point – with so much financial engineering demanding money and people, real engineering doesn’t stand a chance. But it is real engineering that drives industrial productivity.

Financialisation is not just a problem because it drains resources away from industry. In a financialised economy, investors with short-term horizons tend to have more control over firms. This results in less reinvestment of profits and rising burdens of debt that, in a vicious cycle, makes industry even more driven by short-term considerations. In effect, this kind of finance is not neutral but changes the nature of what it finances.

This was seen just recently with the GKN takeover by “turnaround company” Melrose. An estimated 20 to 25 per cent of the shares in GKN were in the hands of hedge funds, many of which were expected to back the takeover – with the firm Elliott Advisors, owning 3.8 per cent of the company, explicitly doing so. The bid was won by 52 per cent to 48 per cent. And Melrose itself is not run in any long-term interest other than maximising shareholder value: it has a long history of operating as a “turnaround firm” and almost a third of its own shares are held by hedge funds. The vote was essentially a referendum about the time horizons of British industry, and Britain lost.

So when bankers and chancellors talk of having learned the lessons of the financial crisis they are wrong both at the macro and micro level. With UK national debt twice what it was in 2007 and household debt to disposable income at a record high, 10 years after the crash of the global economy, finance is once again at the heart of an existential threat to our way of life.

Financialisation and inequality

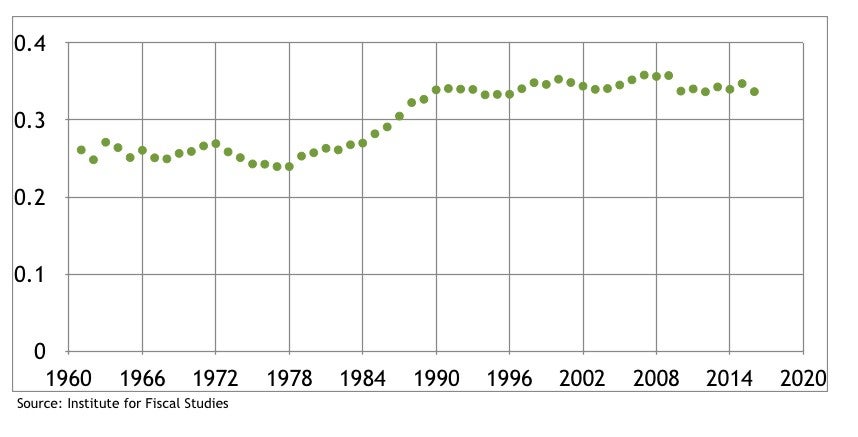

Even before the crash, this “anti-industrial strategy” drove social and geographic inequalities. Levels of income inequality as measured by the Gini coefficient reached a pre-crash peak of 0.35 in the 1990s and, while improving slightly, remained high in comparison to the Sixties throughout the 2000s. Regional inequality was also a significant feature of the pre-crash economy, with data from the National Institute of Economic and Social Research showing a gradual rise throughout the 2000s in the difference in gross household income between regions. In 2005, average household income in the North East was 14 per cent below the UK average, while in London it was 20 per cent higher.

The Tories were either indifferent to these inequalities or at best felt they were an acceptable price to pay. Labour, under previous leaderships, believed that redistributive policies could make it all come out right in the end, and flagship programmes such as Sure Start and working tax credits certainly helped. But both approaches were fundamentally mistaken. Financialisation turned out to be a house built on sand – unable to generate enough wealth to compensate for the abandonment of the rest of the economy, and vulnerable to boom and bust cycles. Ultimately, the financial crisis of 2008 and the global economic crisis it spawned showed that the ideology of finance – that financial markets and institutions, left to themselves and the profit motive, would efficiently allocate capital – was a pernicious fantasy.

British industry—creating real value in the real economy

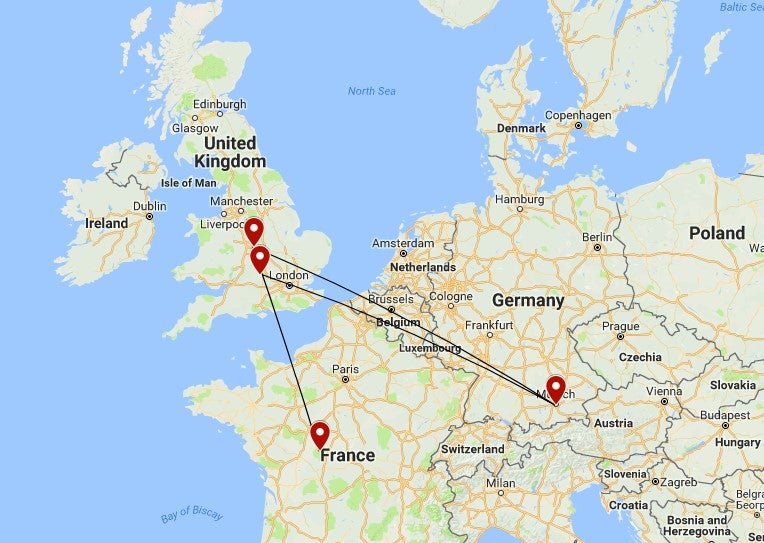

But that was not the whole story. While metropolitan London came to comprise 40 per cent of the British economy – and a 40 per cent heavily dependent on finance and professional services – something else was happening in the rest of the country. Britain’s entry into the European Union, and the survival in parts of Britain of a culture favourable to engineering and manufacturing, fostered the growth of certain sectors of British industry as part of a larger integrated European industrial base. The supply chains of large European firms such as Airbus, Boeing and BMW are substantially British. Nissan’s Sunderland plant is the final destination for parts manufactured across Europe and produces more cars per worker than any other factory in the European Union. And GKN, itself one of the world’s oldest engineering firms, is a key supplier to international aerospace and automotive firms – including European giant Airbus, which warned against the Melrose takeover. Factories engaged in producing components and sub-assemblies and assembling components from elsewhere in Europe are now critical to the prosperity of much of Britain. Figure 1 shows just one of BMW’s many supply chains.

Such integration requires frictionless borders but also agreed standards to define everything from the acceptable frequency of electromagnetic radiation to the atomic composition of a given chemical. Leaving the European Union will not mean less regulation simply more duplication. As they scramble to recreate existing EU agencies and regulations, businesses and government departments are realising that far from Brussels bureaucracy being imposed upon Britain, the European Union was effectively based on the “shared back office services” model that Whitehall now champions for local government.

In many ways, British agriculture has followed a similar trajectory to British car manufacturing, where British farmers have been able to successfully compete on both quality and price in markets defined by EU food safety rules. For example, British farmers export far more wheat flour to the EU – approximately 250,000 tonnes last year – than they do to non-EU countries – approximately 6,000 tonnes. The same goes for other agricultural products such as barley (one million tonnes versus 50,000 tonnes) and oats (16,000 tonnes versus 4,000 tonnes).

The EU is the largest importer and exporter of food in the world. As an EU member state, our farmers have benefited from preferential access to this market through exemptions from the tariffs and quotas imposed on non-member countries. And with 85 per cent of seasonal agricultural workers in the UK coming from Bulgaria and Romania, agriculture is one of the UK sectors most heavily dependent on freedom of movement.

Food and drink is Britain’s largest manufacturing sector and Europe’s complex rules of origin guidelines could lead to a “hidden hard Brexit” requiring the restructuring of food manufacturing supply chains even if we secure preferential access. Agriculture and manufacturing are both more important outside of London and particularly around the very market towns that have been most “left behind” by the new economy.

As Britain contemplates how to engage with the world before, during and after Brexit, we need to understand the trade policy choices we make will drive the shape of our economy and are therefore also industrial policy choices, choices that will shape the very nature of what work we do, the health of our communities and the way we live for decades to come.

The benefits of a customs union

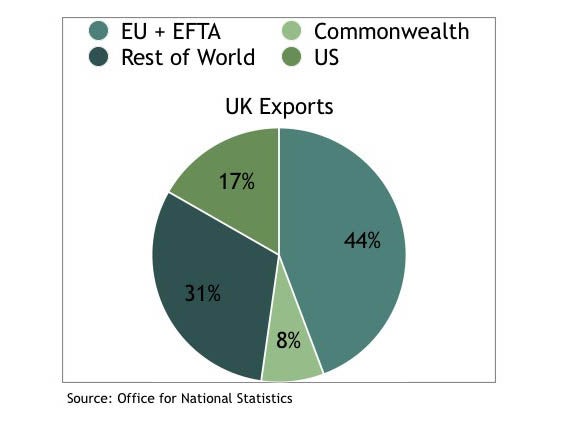

The Labour Party is united in supporting a customs union with Europe. We believe it will bolster our current industrial strengths and offer the possibility of continued industrial revival in certain sectors. We should not be complacent about this approach. Our place in the larger European manufacturing economy will still depend on our ability to innovate and to invest, so that British firms successfully manage and not just participate in supply chains. And this will depend on our learning the lessons of the financial crisis so that our financial markets and institutions actually invest in productive sectors.

Unfortunately, the government continues to act as if the only issues in financial regulation are safety, soundness and fraud. While these are obviously important issues, they completely miss the question of whether our financial system is effectively channelling capital to productive and innovative investment. And this is the whole point of a financial system. A financial system that simply parks money in risk-free assets or honestly gambles on sporting events, would meet the characteristics the Tories have established but would still be a total failure. As Mazzucato argues, the traditional policies we have seen create a “healthy financial sector (bailed out, ring-fenced, and restructured) in a deeply sick economy”.

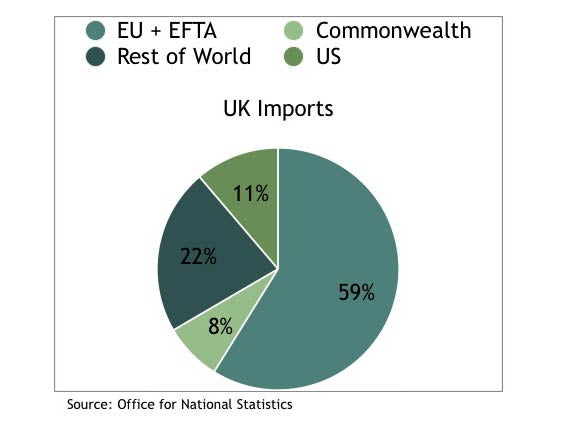

Implications for industrial strategy of the alternatives

Last week’s visit by President Trump to Britain revealed that he thinks the UK-US relationship is “the highest level of special”. Arch Brexiteers argue that he offers an alternative to a customs union with Europe: a free trade agreement with the United States, which, as a consequence of Nafta would really be a free trade agreement with all of North America. But while the US economy is of comparable size to the EU in GDP terms, $19 trillion (£14 trillion) compared to $17 trillion, they have different sectoral compositions and regulatory standards. Going in this direction would lead to substantial changes in the structure of the British economy.

Earlier this year, trade experts at Harvard University published a report that included a candid assessment of obstacles to a US-UK free trade agreement. Its authors, including former shadow chancellor Ed Balls, reached the conclusion that it is “highly unlikely that a free trade deal between the US and the UK will be secured in the near term” and, in addition, “the likely potential benefits for British businesses are less than often suggested”.

The report focused on likely US demands for access to British food markets and likely British demands for access for British firms to US financial and professional services markets. These demands map the likely direction a US-UK free trade agreement would take both countries. Britain is attractive to the US as a market for agricultural products and for goods manufactured through US-controlled supply chains. Britain is also seen by some as a source of relatively low cost financial and professional services. Without an EU customs union, American business does not see Britain as a manufacturing platform – British wages are too high given the distance to the North American market. Labour costs per hour in manufacturing are on average £27 in the US and £23 in the UK – a £4 difference that does not compensate for transport costs.

In a UK detached from the European market, the role of British industry in European supply chains will therefore not be replaced by similar roles in US-based supply chains. This is the critical point for UK manufacturing – we cannot replace European supply chain integration with North American supply chain integration.

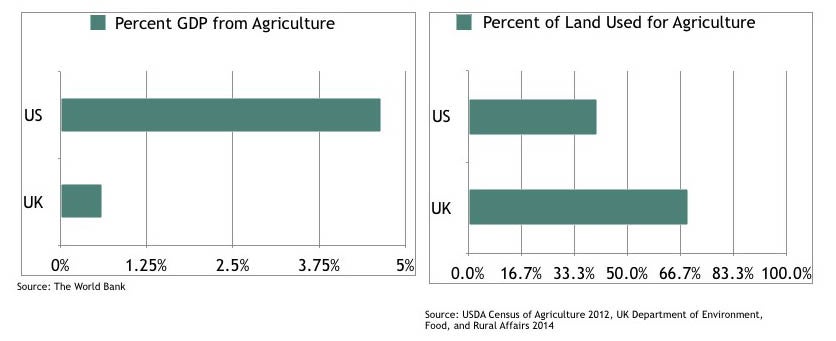

In addition, if British food safety rules are relaxed as part of a trade deal with the US, it is likely that cheap American agricultural products will significantly displace British agriculture. So we will eat chlorinated chicken from Arkansas, bake with GM flour from Dakota and barbecue antibiotic drenched beef from Illinois. US farming is largely in the hands of mega industrial organisations. Agriculture is a much greater proportion of US GDP than it is of UK GDP. There are farms in Texas that are bigger than major UK counties – 500 square miles, for example. We cannot compete with agriculture on that scale without harming our landscape and biodiversity, especially given that we already use substantially more of our land in percentage terms on agriculture than does the US. If our markets are opened up to US agricultural products, UK farming will either adapt to US food safety practices and scale or our agriculture will diminish greatly. If we were to follow the bidding of the arch-Brexiteers and take the US as our model partner it would be the end of our landscape and biodiversity as we currently know it.

In the place of agriculture and industry, there will be a US market for British financial services and other professional services such as law, accountancy and management consulting. However, just as we have seen the integration of British manufacturing into European firms, we will likely see a wave of mergers and acquisitions in services as British firms are acquired by US firms seeking to serve the US market with British professionals. As a consequence, while manufacturing and agriculture would suffer, services and finance might not remain in British hands, especially given the current takeover regime that substantially limits the scope for government protection of UK businesses.

A Britain without a customs union with the EU and with a free trade agreement with the US would have less industry, less agriculture, but more finance and more service sector jobs. It would likely be a Britain of growing regional and social disparities, and a Britain more vulnerable to financial instability. After all, it was the high concentration of financial services in the UK economy that meant we were hit particularly hard by the last financial crisis. If the UK economy consolidates further around finance, then we will become even more vulnerable.

The Commonwealth

Turning from North America some look to the Commonwealth as an alternative future that harks to our past. We have strong ties to English-speaking Commonwealth countries around the world – economic ties as well as ties of language, immigration and history. In a digital world, we have the possibility of building networks of innovation that could contribute both to our own industrial competitiveness as well as the competitiveness of our partners.

Countries as diverse as Nigeria, Australia and India are all racing to be centres of technological innovation and to solve pressing problems in areas such as energy and education. In a sense, if we are open to our former colonies as partners, and generous with access to our own centres of innovation, we could perhaps create alternative pathways to competitiveness for our industry.

But those same countries have requested access to the UK through preferential visa arrangements as part of any free trade agreement. India has requested an increase in the number of visas issued to skilled Indian workers and allow students to stay for longer after graduating, but so far government has refused calls to relax visa rules even within the current framework. Australia and other Commonwealth countries want their citizens to be granted the same rights as Europeans: to live and work in the UK after Brexit.

Building a competitive commonwealth innovation network effectively requires the opposite of our current attitudes towards the Global South. Commonwealth leaders have criticised the government’s – reported – characterisation of post-Brexit trade as ‘Empire 2.0’. This was reflected in our treatment of the Windrush generation, which, in a sense, like our approach to Brexit, threatens to close critical doors to a better future for British industry and for Britain as a whole.

Whether we look to North America or the Commonwealth, into our past or forward to the type of economy we want to become, the arguments bring us back to a customs union with the EU and an industrial strategy that will help rebalance the economy and provide the directed investment to get it growing again. The billions poured by the Bank of England into quantitative easing have signally failed to do this.

A Labour government would invest £250bn over 10 years through our National Transformation Fund, and set up a National Investment Bank, as well as a network of regional development banks to channel investment into productive enterprises across the country, unlocking productivity and creating growth.

Conclusion

We need to understand as we approach critical decision points around our trade policy and our financial regulatory policy that these are choices that will shape not just our relations with the outside world but Britain itself – that choices labelled trade policy or immigration policy or financial regulatory policy are in fact industrial policy, agricultural policy and economic policy.

The Tory party ideologues are in no state to set out a vision for our future economy, far less to rationally assess the policies needed to make it a reality. Financialisation has proven to be an economic dead-end, creating wealth for the few at the expense of social equality, regional balance and long-term productivity growth.

To build a more competitive and equal Britain post-Brexit we need a deal that strengthens our productive sectors such as manufacturing rather than one that deepens financialisation and risks our long-term prosperity. We also need a real industrial strategy based on our regional strengths that enables investment in the productive economy, delivering jobs in our towns as well as our cities that creates value regionally and nationally that can be shared by all.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments