Brexit is the perfect example of self-deprecation. The problem is, it’s not funny any more

Peter Krijgsman – a Canadian-born holder of a Dutch passport and a UK resident since 1965 – was devastated when Britain decided to leave the EU in 2016. Now, even many of those who voted to go are feeling sickened

I was 17 when the United Kingdom became part of the European Economic Community – the same age as my English mother on the day Great Britain declared war on Germany in 1939, and two years younger than my dad when he watched the Luftwaffe flatten his home town of Rotterdam the following year.

Comparing my experience to that of my parents, joining Europe should have felt like a seminal moment – the epitome of human progress in a country still recovering from the Second World War. I would like to say that I felt some sacred revelation of peace and harmony overlaying strife; but I can’t, because I didn’t.

This happened at the start of 1973. Hopeless “Grocer” Heath was the British prime minister and “Tricky Dicky” Nixon was president of the United States. Industrial disputes were back to back. The Vietnam War was tragic, miserable, incomprehensible and worst of all still happening. Meanwhile, in my privileged parallel universe, Jimmy Osmond had been at Number 1 since Christmas and would still be hanging around the charts for weeks. It was no time to celebrate.

As an event, from memory, the UK joining the EEC was hardly visible. Certainly, Europeanisation was no match for the cultural march of the yankee dollar. As well as Little Jimmy O singing his mini-Mormon heart out, we were overrun by Americana – Levis; hamburger, pizza and texmex joints; west coast music; TV and Hollywood.

From the other side of La Manche, good croissants wouldn’t arrive for another five years. While Truffaut made a few art house appearances for those of us studying the deeper reaches of the Time Out listings, cinema was wall-to-wall Hollywood, with a dash of Pinewood thrown in to season our cultural diet. As for music: let’s not go there. It would be many, many years before Johnny Hallyday became cool.

So, in 2016, why did I feel so bad about something being voted away that, in all truth, I had hardly noticed in 43 years?

I hadn’t worked in Europe apart from a brief spell in the Seventies as a Tefl teacher in Paris, and I don’t believe my holidays there were unduly influenced by some EU esprit de corps. My work in financial journalism and PR had never required me to take much interest in European institutions, except those with an office (and probably an Anglo-Saxon boss) in the City of London.

Yet I find Brexit heartbreaking, profoundly, from the point of view of both Europe and Britain. I cannot shake the strong sense I had on the day of the result, of things having just gotten a bit worse, with a lot more to come.

I fear that the pain of Brexit will stem from a massive number of little, hard-to-isolate things rather than the big items favoured by politicians and headline writers. Historically, the EU’s lack of visibility was down to its working most effectively at the micro level. Here, among the complex, technical dimensions of supply chains, quality controls and food standards, it could exert influence without resistance and controversy. Its favoured media would have been sober trade magazines rather than the more febrile voices of Fleet Street. I fear that most of the promoters and supporters of Brexit had no sense of this when they started and probably still don’t.

I had a gig, the night of the referendum result, playing at my friend Robert Cole’s 50th birthday party at the Rivoli Ballroom in Brockley, southeast London. We rehearsed on the day of the vote when I remember Robert, a quintessential London optimist (that is to say a chirpy pessimist) saying that no one was prepared for a “leave” decision and that we were “in the hands of the great British electorate”. I remember thinking, “Well, that’ll be alright then”.

We rehearsed on the morning of the result in a state of shock that would last for weeks. When the party finished, I drove home like a man on the run. Adrenalin sustained me as far as Stone Henge, when I noticed the sun starting to lighten the sky in my rear view mirror. I slept for two hours in the car park of the Holiday Inn before a slap-up in the Little Chef down the road. I was trying to pin some normality back onto the board after the earthquake – a few familiar, enjoyable acts. I read the paper, drank coffee, smoked illicit cigarettes. I felt hollow. The world had changed overnight and left me behind.

A rule too far?

I have a letter on file from Mrs S Hadfield at the Nationality Division of the Home Office, dated 3 April 1980. It is a response to a letter that I’d written 15 months earlier to enquire about naturalisation procedures. Until then I’d been a Dutch diplomatic passport holder, courtesy of my father’s job. (I had been born in Montreal and first moved to London in 1965.)

Long before the Windrush scandal vapourised any temptation to find humour in the Home Office, her letter was a clue to where English satire came from: “...please note ‘D’ on page 3 of N156 which again states that no application will be entertained from a person whose stay in this country is subject to any restriction.”

Rather than dwell on this philosophical conundrum, I acquired a residence permit. But none of it seemed to matter. Nobody – employers, doctors, border guards – asked what I thought I was doing, living in England when I was not, you know, English. Nobody asked to see my residence permit when I changed jobs or needed medical treatment. One day, I took it to the police station to renew the thing and the officer told me it wasn’t necessary anymore.

Organisations now create rules at the same rate as teenagers make YouTube videos... people are entitled to be grumpy about it, but Europe is the wrong scapegoat

I still don’t know what had changed to make this so, but I put the whole experience down to one of my favourite English characteristics – unruliness. To me, at that time, English people liked to push boundaries rather than respect them. Conventions were there to be challenged and tested or ignored rather than imposed. There were no obvious rules stating that I should present my “papers” before enjoying the privilege of accommodation or employment as might have been the case, say, in France.

Things have changed since then. Now rules are everywhere in suffocating abundance. I fear that the naturally unruly Brits have pinned the blame for this intrusion on Brussels and Europe’s Code Civil usurping English common law. In fact the true culprit is probably the internet. Unrestrained by the cost of printing and mailing, organisations now create rules at the same rate as teenagers make YouTube videos. People are entitled to be grumpy about it, but Europe is the wrong scapegoat.

Citizens of the world unite

Early in 2017, before the first wave of government assurances to EU citizens living in the UK, a friend expressed surprise that I was worried about Brexit threatening my residential status here. “But I always think of you as British,” he said.

Like Peter Ustinov used to say, I can feel very British on occasion, but usually it’s when I am in a foreign country. Even then it is tempered with a nod to the (still) Dutch passport, another to the Canadian place of birth and residual accent, and yet another to the fact that none of these places claim me absolutely.

You can’t be a three-nation patriot, which is perhaps what Theresa May meant when she gave that “citizens of nowhere” speech after becoming leader of the Conservative Party. Claiming England as my own after all this time would be a little dishonest. I have the greatest respect for the English people, but I am not of this nation. I am of elsewhere. While “citizen of the world” is a meaningless phrase, it will have to do. Mrs Hadfield gave me no option.

On 1 January 1973 I was living in southwest London and studying for A-levels – the culmination of a peripatetic education, attending nine schools in three continents over the previous eight years. In September 1972 I’d landed like some exhausted, oversized migratory bird at Kingston College of Further Education.

By the time I’d reached my previous berth – a gothic boarding school in Essex – I’d finally run out of patience and ran away from school. I was lucky to have been caught mid-flight by my friend Nigel, who persuaded his family that I was worth rescuing. They took me in at their large, pleasingly shambolic house in Putney – an act of unforced kindness that conditioned me into believing that England was home to the most civilised people on our planet.

Nigel’s family was different to mine: argumentative and affectionate in equal measure, where mine was more reserved. His grandmother Kath and I would often talk in the evening, if she was still up watching TV when I got home from a night out. She liked to recount tales of her son Arthur’s wartime exploits as a Royal Marine commando. The Arthur I knew was by then a large and jovial police sergeant/dog handler, usually accompanied by a huge German shepherd. But he did give you the quiet sense of being handy with a garotte.

Sometimes, Kath would break off her story and fix me with an unnerving stare. “Yes, I can see there’s a lot of German in you,” she would say.

Despite the pageantry and promises of Remembrance Sunday, England has forgotten the horrors of battle

It was an observation not a criticism. Even Arthur, who had killed lots of Germans in his day, was complimentary about them. But my “German-ness” – Dutchness, in fact – put a distance between me and Kathleen. It was not a distance that undermined friendship because the English tribe – this one anyway – was distinctive for its liking of strangers. It was just there. It taught me that being welcomed and accommodated with kindness is not the same as being an integral part of something.

That was how I came to trust England. Not only did its people welcome me as a stranger, but they never showed any sign of wanting me to be anything else.They were not just kind, but tolerant and confident enough of their place in the world to embrace the strangers in their midst.

If anything, my foreignness in 1973 seemed more asset than liability. A revolution in attitudes towards all manner of relationships was challenging the old models of human existence. Church, family, school and state were being questioned and prodded just as radically as social media challenges them today (although we didn’t insist on breaking them completely à la Facebook).

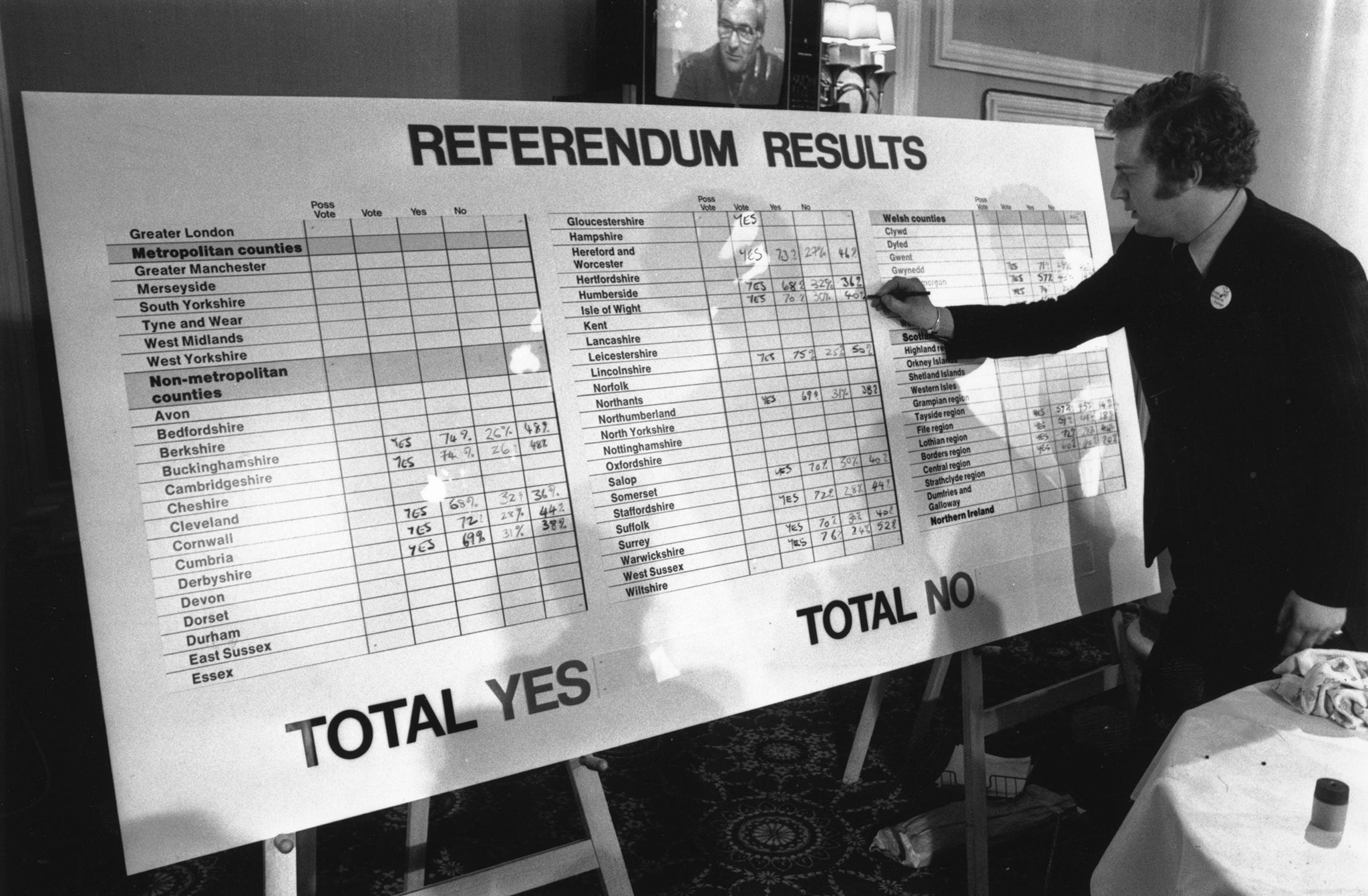

The industrial-military complex was exposed, ridiculed and decried; European dictatorships – Greece, Portugal, Spain and later the Soviet satellites – were replaced with democratic governments; the Cold War, having peaked with the Cuban missile crisis in 1962, was beginning a long, awkward thaw. There was plenty of naivety around and plenty of causes still to be addressed, but on balance it all seemed to be going the right way. The EEC seemed a natural part of this peaceful, optimistic outlook. The result, in 1975, of Britain’s first referendum on the question of leaving or remaining – with over two-thirds voting to stay – seemed to reflect this.

There has been much analysis and speculation as to why the 2016 referendum had such a different result to the 1975 version. The most obvious explanation is that the country saw less to be optimistic about than it did 41 years earlier. It doesn’t quite explain why everybody was so angry when most of the long-term indicators that matter (ignoring climate change, which we always, sadly, do) were still more or less positive and a long way ahead of where they were in 1975. So we still need our theories. Apart from the often quoted and compelling one of a protest against an out-of-touch political establishment, I have three.

Digital dementia

In addition to encouraging a vast panoply of regulation, a further unwelcome biproduct of our dominant digital technology is the tendency to polarise. Computer programs and their sequences of ones and zeroes, are in some strange how shaping the way in which we ask questions and frame answers – blacks and whites, yeses and nos, pluses and minuses. We have lost the patience required for in-between options, shades of grey and “maybe”: the places in human life where art used to cushion the hard edges of science. In the parlance, we have become more transactional.

In addition, the modern polarities, as expressed through social media, are both multiple and coincidental: racial, religious, sexual, financial, political, cultural and more. Our capacity for rational response is overloaded and overwhelmed. Trying to find perspective is like trying to get your bearings in a blizzard.

In the context of the debate around Brexit, EU opponents and supporters alike can cherry-pick social and news media ad infinitum, trawling through reports, fake and real, of EU disasters and triumphs respectively, repackaging and redistributing them to shore up their competing agendas. As everyone now knows, both sides have a point, but there are no “likes” for the median or average position.

Funny money madness

My second theory is that the great financial crisis of 2008-9 and its subsequent free-money cure has caused English people to lose their minds, or at least their memories. After a decade of state-depressed interest rates they’ve forgotten how hard things can get when an internationally exposed country takes an unconventional political or economic turn. After 10 years of interest rates close to zero, they have forgotten to measure the impractical promises of politicians against the high price for them that will in time be extracted by the money men.

England has always had an ambivalent relationship with money, despite London being the financial capital of the world. After the 2009 crash, ambivalence was replaced by neglect. Money became irrelevant when interest rates went to zero, pay stopped growing and houses, if you were lucky enough to own one, became the only dependable store of value. (If you weren’t, home ownership was too remote a possibility to bother saving for.)

In discussing this topic, my geologist friend, Dr Danny Clarke Lowes noted that “we seem to have arrived in a situation where the voice of reason has lost its power to influence outcomes”. This phenomenon has financial as well as political roots. The central bank policies deployed to remedy the 2009 crisis have anaesthetised risk and reward as expressed through the rate of interest charged on capital. This has in turn empowered demons who might otherwise have been constrained by the common sense of markets. You could reasonably speculate that one of these is Donald Trump.

Sheer, simple aggression?

All that said, social media contretemps and financial shenanigans are preferable proxies for human conflict, compared to war itself. My third theory is that, despite the pageantry and promises of Remembrance Sunday, England has forgotten the horrors of battle. The countdown to Brexit feels like a countdown to conflict that its right-wing leaders are relishing.

I confess to a pacific nature. English people – all the nations of the British Isles – have a fighting instinct that is alien to me. The Falklands War and its unanimous popular support (over the pursuit of a diplomatic solution) came as a surprise, not unlike the referendum result. Europe today is not Argentina in the early 1980s, although you might be forgiven for wondering when you listen to the lead Brexiteers

That’s what really worries me – what is yet to come and what it will tell me about who the English really are

The Anglo-Saxon experience of the Second World War (as victors and liberators) rather than the continental experience (of being victims, occupied nations and, indeed, aggressors) coloured perceptions of the new economic alliance. But every O-level historian knew the underlying logic: if you promote economic union, political cohesion will follow. To say that the UK joining the EEC had had nothing to do with politics is disingenuous. Above all, it was designed to defuse the war gene that had blighted Europe for centuries. There are innumerable reasons why the EU is bound to fail. This is the forgotten reason why, in one form or another, it must survive.

We know the EU’s faults – its tendency to overreach, its unsustainable currency and its essentially clinical heartlessness, being an artificial institution with no national culture to give it emotional resonance. We know that it may well end in tears. By leaving, England is depriving both Europe and itself of an opportunity to rebuild something from the wreckage. If Europe blows, it will be left to Germany and France to carve out the solution. Britain’s traditional modifying and pragmatic voice, assuming it still exists somewhere, will not be heard.

Happy endings for some

My Dutch father once said, at the height of the earlier British financial crisis of 1976, that English people were very clever, that they always find their way back in time. So how and where will this end? In 1976 a succession of economic catastrophes had led the country to seek help from the International Monetary Fund. The aftermath of that led eventually to the base radicalism of Margaret Thatcher and the brutal destruction of communities and industries that would cost too much to modernise or wind down in a humane fashion.

One could surmise that the more extreme Brexiteers want to see that happen again. Many seem to hunger for the blood denied them after the 2009 crash, when slump was averted by prime minister Gordon Brown, who was markets-savvy enough to prescribe the immediate cure, though not the longer term one.

It is difficult to see how the Thatcher pattern could repeat. There is no North Sea oil cushion this time round. There is not much left to privatise. There is no union power to dismantle. The management class is professionalised, unlike in 1979, and government finances are overstretched. Even the great economic promise of the internet and communications technology is starting to look a little old hat.

One can only predict that the next crash will take us somewhere we haven’t been yet, somewhere that will be painful for less productive segments of this country, rewarding for others. Scapegoats will be sought. EU “intransigence” will top the list.

But, as I keep hearing, it is not just about economics, this Brexit business. If it were, the country never would have voted to leave the EU in the first place. It is about something else, something the country hasn’t said yet. That’s what really worries me – what is yet to come and what it will tell me about who the English really are.

The last laugh

Contrary to rumour, Tom Lehrer never pronounced political satire to be dead when Henry Kissinger received the Nobel Peace Prize in December 1973. He merely said it was “obsolete” – still a weapon of sorts, in other words, but no longer effective against better-equipped opponents.

Satire took another step down the road to mortality with Brexit, with the best jokes getting cracked by the worst people. Boris Johnson, who never shone in political office, was hilarious in The Spectator and The Telegraph in the days when his pokes at Europe were not life threatening. Nigel Farage’s EU parliament speeches, deflating the pomp of dignitaries with unfortunate Flemish names and odd views about cucumbers, raised important issues about accountability as well as smiles.

They were rude and politically incorrect at a time when incorrectness was, increasingly, frowned upon, and thus increasingly irresistible.They became unamusing once they were deployed in the cause of Brexit – as in it’s not funny to hear a surgeon cracking jokes about your forthcoming heart transplant or the pilot of your little private plane boasting about how much he’d been drinking the night before. The subject is serious. The people who are still laughing are either unaware of the danger they’re in or they have agendas in which danger (and mainly to others) is part of the plan.

One of the last things that we are allowed to laugh about these days is ourselves. Britain lost the right to self-deprecate with Brexit, because the movement’s defining premise appears to have been an overriding belief in this country’s innate and exceptional superiority.

Britain may regain the right to self-deprecate, one day, after Brexit’s chickens have come home to roost and the casualties have been counted. It will take a lot longer before it seems funny again.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments