If only the politicians of yesteryear were around to handle Brexit

Andrew Grice fears that the calibre of Britain’s political classes has declined, with many just desperate to be popular. But which MPs from the past would have been best placed to resolve the Brexit conundrum?

The turmoil over Brexit raises big questions about the ability of today’s politicians. Would their predecessors have done a better job, and prevented the drama of the 2016 referendum result turning into a crisis? In my time as a political journalist, the calibre of our political class has changed, and for the worse.

When I landed in the Westminster village in 1982, some big beasts from the past still roamed – among them Denis Healey, Roy Jenkins, Edward Heath, Tony Benn and Enoch Powell. They, and contemporaries who had already died – such as Rab Butler, Iain Macleod and Anthony Crosland – have been called the “golden generation”.

Many were intellectual heavyweights. Some had expected a career in academia, but went into politics after distinguished service in the Second World War, with the noble ambition of preventing a repeat. Similarly, some had seen the deprivation of 1930s Britain and vowed “never again”. Politics was a natural path for the nation’s brightest and best.

Today’s politicians have been fortunate enough not to experience war in a Europe scarred by centuries of it. They govern in very different circumstances.

The post-war consensus on rebuilding Britain, a universal welfare state and wider educational opportunity, ended in the Thatcher era. The common enemies of fascism and then communism have been replaced by a search for enemies and scapegoats closer to home, whether immigrants or the EU. The UK has been deeply divided since the 2016 referendum, which was a protest vote against Westminster as much as Brussels.

Theresa May and Jeremy Corbyn are accused by critics of showing poor leadership at a time of national crisis. To try to hold their divided parties together, both prefer prevarication and procrastination to decisive action. It is unusual for the two main party leaders to look weak at the same time. The historian David Starkey has described “a parliament of pygmies”, who “think they are giants and ape the gestures of the parliamentary greats of the past.” A survey by ComRes found that 75 per cent of people agree that the Brexit process has shown the current generation of politicians is not up to the job, while only 8 per cent disagree. Some 72 per cent think Brexit has shown the political system needs a complete overhaul; only 10 per cent disagree.

I hope my view is not coloured by rose-tinted spectacles, but I think the post-war generation would have handled Brexit better.

To start at the top, no one can doubt May’s determination or commitment. Her daunting task would have defeated many others. Some politicians on both sides of the Channel believe any prime minister would have ended up with a deal very similar to the one she got.

I disagree. May made mistakes early on. She could have interpreted the 2016 referendum as a vote to leave the EU institutions but stick close to the UK’s biggest market to protect trade, jobs and investment – potentially appealing to both the 52 per cent and the 48 per cent, instead of treating the latter as if they did not exist. She might have ended up with a Norway-style deal that won a cross-party Commons majority.

72%

think Brexit has shown the political system needs a complete overhaul

Instead, heavily influenced by her coterie of political advisers, she opted for a hard Brexit outside the single market, customs union and remit of the European Court of Justice. Worryingly, some senior civil servants believe she simply did not understand the implications; her priority, as a Remainer, was to reassure Tory Leavers. Hence her mind-numbing soundbite “Brexit means Brexit.”

Later, May tacked towards a softer Brexit to cushion the economic impact, but ended up with a dog’s breakfast deal because of her initial red lines. Crispin Odey, a Brexiteer hedge fund manager, said May had “provided an O-level answer to an A-level question.”

When May became prime minister in 2016, it was a case of last woman standing after rivals deserted the battlefield. She has clung on despite calling a general election which threw away the Tory majority; making the most disastrous party conference speech I have witnessed; and suffering the biggest Commons defeat in history. Some 32 ministers and ministerial aides have resigned since 2017, mostly over Brexit. May survives because Tory MPs are not sure her would-be successors could do a better job, and because those who covet her job would prefer her to clear up the Brexit mess.

Even May’s allies admit she lacks vision; some ministers describe her as “a blank sheet of paper” and “an empty vessel”. Even if Brexit had not been all-consuming, she might have struggled to put flesh on the bones of her domestic policy goal to tackle “burning injustices.”

In 2016, the last woman but one standing was Andrea Leadsom, now the Commons leader. During the Tory election, a group of her supporters staged a march on Westminster, chanting: “What do we want? Leadsom for Leader! When do we want it? Now!” While most of Westminster laughed at this infantile gesture, it recently emerged that Chris Grayling, the chair of May’s campaign, was so worried that he suggested it should stage a rival march. Thankfully, the Eurosceptic transport secretary was sent packing.

Even Brexiteers are hardly flattering about the brainpower of their allies in the cabinet. One said: “They’re like something from the Wizard of Oz. There’s Grayling, the man without the heart, Andrea, the one without the brain, and Michael [Gove], the cowardly lion who didn’t have the nerve to resign.” David Davis, the former Brexit secretary, was described as “thick as mince, lazy as a toad, and vain as Narcissus” by Dominic Cummings, head of the Vote Leave campaign.

Backbench Eurosceptics include intelligent people like Jacob Rees-Mogg, once a caricature of himself but who now features in the bookies’ odds for the Tory leadership stakes. Yet his political skills were called into question by the recent failed coup against May.

One of the most widely quoted Eurosceptics is Andrew Bridgen, dubbed “thick as mash” by some fellow Tory MPs as he has a vegetable prep business. Responding to gruesome anonymous statements by Tory critics saying May should “bring her own noose” to a meeting with her MPs and would be “knifed in the front”, Bridgen suggested the quotes had been invented by Downing Street. He told one newspaper May would be booed at last year’s Tory conference, another that she would be greeted by an empty hall. Neither happened. He said all Brits were entitled to an Irish passport; they are not.

Being bright doesn’t necessarily make you a good politician.

If Tory members had the sole right to choose the next leader, they would probably elect Boris Johnson. (They select from a shortlist of two chosen by the party’s MPs). His classics degree at Oxford means he can quote great scholars in the original Latin or Greek. He is a good writer who would like to emulate his hero Winston Churchill. Yet many fellow Tories believe Johnson proved a woeful foreign secretary and wonder whether he is up to the top job.

I’m not making a party political point. Many of those currently on Labour’s front bench are there because they remained loyal to Corbyn in 2016, when 47 opposition spokespeople quit their jobs during an attempted coup against him. Several on today’s front bench would be regarded as natural backbenchers in previous eras.

There is no place for the “shadow shadow cabinet” who deploy their talents as select committee chairs or backbenchers – Yvette Cooper, Hilary Benn, Rachel Reeves, Chris Leslie, Chuka Umunna.

In 1976, when Harold Wilson resigned as prime minister, the Labour leadership was contested by six undoubted heavyweights – James Callaghan (the winner); Michael Foot; Benn; Crosland; Healey and Jenkins. In 2015, Labour’s contest was between Corbyn, Andy Burnham, Liz Kendall and Cooper.

Are today’s politicians the best and brightest of their generation? I’ve heard MPs say they could double their £77,000-a-year salary in the private sector. True for the few, but not the many, I suspect. We have seen the rise of a political class with little experience outside politics. In 1979, 21 MPs had previously worked in politics. By 2015, the figure was 107. The number who had held white-collar jobs increased from nine to 71, while the number of manual workers fell from 98 to 19.

In some ways, MPs have become more representative of the country they serve. When I arrived, there were 19 women and 616 men. The proportion of women has risen from 3 per cent to 32 per cent today – better, but still not enough. The number of non-white MPs has grown from four in 1987 to 52, but at 8 per cent does not yet reflect the country (14 per cent).

Revealingly, the proportion of Tory MPs educated at Oxbridge has fallen from 49 per cent in 1979 to 34 per cent today, although among Labour MPs it has remained steady at about 20 per cent. The proportion of MPs who attended private schools has fallen to a new low of 29 per cent, but is still higher than the national average (seven per cent).

In the post-war period, MPs were either what Tories called “men of affairs” (at work, though often in the other sense too), destined to become ministers; or backbenchers who often had a job outside parliament in business or the law. Indeed, parliament’s hours were designed around their other jobs. MPs did not feel compelled to have a base in their constituency; the joke about their annual visit was reality for some Tory grandees. This presents a sharp contrast with today’s generation, who have become full-time, super councillors or glorified social workers; most feel the need to have a home in their constituency.

In my experience, today’s MPs are equally committed to public service than those I got to know in the early 1980s. They work harder, due to the constituency casework, and waste less time drinking in Westminster’s bars. Their desire to react to social media on a 24/7 basis allows them little space to think. Many seem desperate to be popular. We have all become more self-obsessed in the selfie era; MPs are no different.

Ministers work harder too. Many do have not much of a life outside politics, which is another contrast with the golden generation, who believed that having what Healey called a “hinterland” made them better politicians. Jenkins claimed never to take work home, and that he re-read the works of Proust while home secretary.

Yet a culture of short-termism has left governments looking no further than the next election. Little wonder, then, that big issues requiring a cross-party consensus like social care are put in the “too difficult” box. As the political merry-go-round gets ever faster, prime ministers opt for quick fixes like cabinet reshuffles, which rarely make much impact on the big issues. We have had 22 housing ministers in the past 30 years.

New MPs seem much more ambitious; most aspire to reach the top of the political ladder, even if they don’t admit it; few contemplate remaining a backbencher forever. They are too impatient to serve the apprenticeship on the backbenches required of their predecessors. Promotions are more rapid for the ultra-loyal.

At the same time, today’s career politicians lack the self-confidence of previous generations. The scandal over parliamentary expenses in 2009 tarnished their reputation in the eyes of voters, aided by national newspapers which often show little respect for politicians, and have gone from being sceptical to cynical about them.

In an excellent new book, Why We Get the Wrong Politicians (Atlantic Books), The Spectator journalist Isabel Hardman concludes that “our MPs tend to be hard-working and sincere in their desire to make the world a better place. But they are drawn from too narrow a pool to ensure that we get the best politicians with the best breadth of experience.”

Hardman noted the political parties’ crucial role in filtering would-be MPs. Her survey of 532 candidates at the 2015 general election found they spent an average of £11,118 of their own money, with 11 spending more than £100,000. The average personal cost for a Tory who won a marginal seat was £121,467. These bills are a barrier to working class people entering politics unless they have already made money.

Of course, once you have made it to Westminster, there is little incentive to change the system. Ambition encourages MPs to become party “yes men” rather than effective legislators. Sir Graham Brady, who chairs the 1922 committee of Tory MPs, says the way the Commons works “infantilises MPs”.

Without reform, Hardman believes, “we will continue to get a self-selecting bunch of people who think that this sounds like a sensible and financially viable thing to do”. She says: “Westminster is a profoundly odd world that attracts more than its fair share of people who, if not officially weird, are at least from one particular social group, who then socialise with that particular social group.”

A reformed system would give “the best, not merely the best-placed, the chance to be the most effective politicians we could possibly hope for”. But it would still involve “humans, who are all flawed, sometimes selfish and sometimes stupid”.

My worry is that politics will not attract the brightest and best while politicians are the subject of vile abuse and threats of violence, whether on social media or in the street. Women MPs having to barricade their homes to protect their children will hardly help us persuade the more women we need to become candidates.

Perhaps we are a big part of the problem, and get the politicians we deserve.

* * *

So, which politicians from another era would have made a better job of Brexit than today’s generation?

Sir Winston Churchill

Cometh the darkest hour, cometh the man. His Conservative colleagues had grave doubts about him taking over from Neville Chamberlain in 1940, but he confounded his critics. He had the honesty to tell voters he had nothing to offer but “blood, toil, tears and sweat.” He united the country against a common enemy with dogged determination. But today’s divisions might have proved harder to heal.

Leavers and Remainers still argue about Churchill’s views on Europe. He was dubbed “the father of Europe,” but his call for a “united states of Europe” envisaged Franco-German reconciliation rather than UK membership of a federal Europe. “We are with Europe, not of it,” he wrote.

He would have been well qualified to deliver a Brexit in which the UK hugged Europe close. His powerful oratory would have allowed him to tower above today’s soundbite generation.

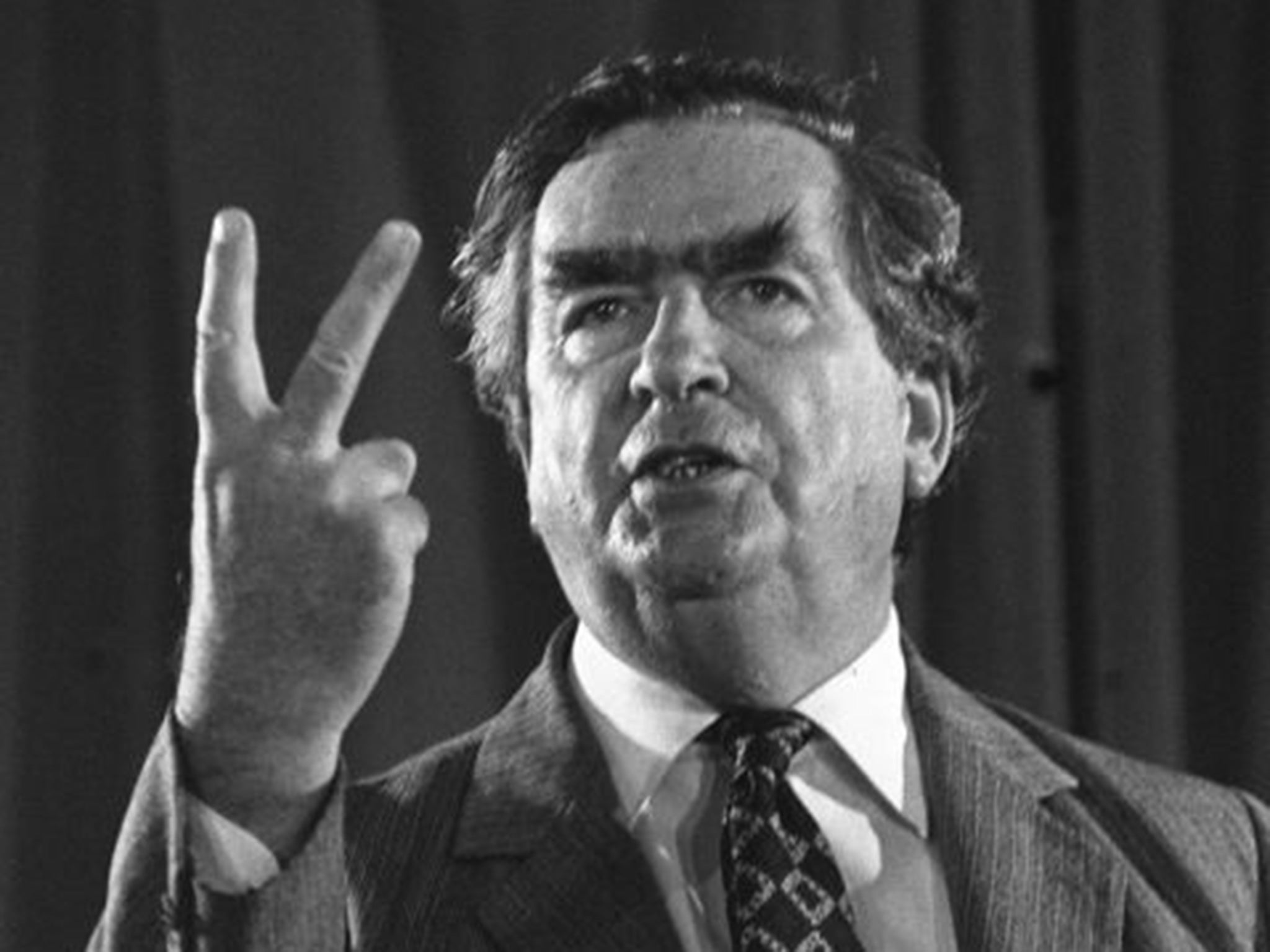

Denis Healey

One of the best prime ministers we never had. The Labour politician was a bruiser prepared to take on his own party and its trade union allies in the national interest. As chancellor he forced through painful spending cuts in 1976 to secure an International Monetary Fund bailout.

A patriot who was hawkish on defence, his bravery was shown as beachmaster at Anzio, south of Rome, in the crucial 1944 allied invasion.

Healey voted against the Conservative government’s application to join the European Economic Community in 1972 and opposed political and monetary union. In 2013, two years before his death, he said: “The case for leaving [the EU] is stronger than for staying in.”

His doubts about the EU project, his intellect and his pugilistic skills would have made him a skilful negotiator. His engaging personality would have helped him win public support for his withdrawal agreement.

Tony Blair

The former Labour prime minister sold the UK to a sceptical EU but never sold the EU project he believed in to sceptical UK voters. He probably could have done so if he had tried; his record of three general election victories speaks for itself.

If the 2016 referendum had happened on his watch, the great communicator would have made an infinitely better job of selling the resulting deal to the public than Theresa May has.

In his “walking on water” phase, might his personal popularity even have persuaded voters to think again about leaving the EU? If not, he could have surely have won their backing for the softest possible Brexit.

True, Blair would have struggled to win public trust if Brexit had happened after he misled them over Iraq’s non-existent weapons of mass destruction. But remember, he still won a majority of 66 two years after the Iraq War.

Kenneth Clarke

A Tory MP since 1970, he is now father of the House of Commons. The best leader his party never chose – because of his pro-European views. His vast experience in several cabinet roles and pragmatic approach to politics would have made him well-suited to handling the Brexit crisis.

He would have stood up to hardline Eurosceptics to prevent their tail wagging the Tory dog. Would he have split his party? Not necessarily. He is no fan of referendums and would never have called one on Europe. If he had inherited a public vote for Brexit, Clarke might have been tempted to say it was only advisory. Probably he would have ended up building cross-party alliances to deliver a Norway-style soft Brexit, which Theresa May hinted at but then backed away from. Despite his Europhile views, he voted for May’s deal when it was rejected by 230 votes.

Clarke’s communication skills and plain common sense would have made him an effective leader at a difficult time.

Don’t agree with Andrew Grice’s selection? Let us know which quartet you’d choose to get a grip on Brexit by emailing letters@independent.co.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments