100 years of film in Bradford: How the West Yorkshire city became the Hollywood of the UK

People were amused when Bradford was named the world’s first Unesco City of Film in 2009. But with a filmmaking history that goes back further than Hollywood, the city is having the last laugh, says David Barnett

In the spring of 2009, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation prepared to announce where in the world would become the very first place to be designated City of Film. Who would scoop this prestigious Unesco honour? Surely Los Angeles, whose Hollywood district is synonymous with film itself, was leading the field. Cannes, perhaps, or Venice, home of the world’s most glittering film festivals.

When the announcement came in June of that year, there was a collective, rather nonplussed pause. The first ever Unesco City of Film would be… Bradford, in West Yorkshire.

A decade ago, Bradford was rarely in the news for the right reasons. The riots of eight years previously were still being picked over and analysed as the city often found itself pitched as some kind of race relations battleground. The far-right British National Party had been making gains on the council for a couple of years and in 2010 the English Defence League would build up to a massive rally there. The global recession and subsequent credit crunch had hit Bradford particularly hard, evidenced by a huge hole in the city centre, where blocks of old shops had been demolished to make way for a shiny new shopping centre that was mothballed for years before a brick had even been laid due to the country being plunged into austerity.

On the face of it, there was no earthly reason why Unesco should choose Bradford, save perhaps pity. And that’s something that still rankles slightly with David Wilson, the director of Bradford City of Film.

“What people didn’t realise was Bradford’s rich heritage in filmmaking,” he says. “It’s been happening in the city for 100 years. No one really realised it at the time, but Bradford was the perfect choice.”

In fact, Bradford’s association with films goes back further than Hollywood’s. A Bradford man called Richard Appleton was dubbed the “First Knight of the Camera” for his pioneering work with film. In 1897, he shot footage of Queen Victoria’s diamond jubilee celebrations and processed it in an ad-hoc darkroom set up on the train from London to his hometown, just in time to show it to aghast audiences in Bradford city centre. Hollywood didn’t start producing movies for at least another decade.

Not long after that, a studio was set up in the city that began turning out the adventures of one Captain Kettle, short films that proved immensely popular in the turn-of-the-century years that formed the infancy of film.

Wilson vividly remembers the first time he made the connection between Bradford and the world of film when as a young man a friend persuaded him to go to watch a showing of the 1963 classic Billy Liar at the Bradford Playhouse. He confesses, “I couldn’t understand why I was there, why I’d been dragged to see this old film. And then I realised that it was Bradford up on that screen. It was something of a transformative experience.”

Billy Liar was by no means the only movie to be shot in Bradford. Filmmakers were attracted by its sweeping Victorian architecture, a hangover from the days when wool trading made Bradford one of the richest cities in the world, and the stunning countryside all around. The old grandeur and natural beauty were counterpointed by a modernist, northern vibe that made it perfect for movies such as Room at the Top (1959) and its 1965 successor Life at the Top. The railway tracks that cleaved through the valley that had Keighley at one end and Haworth at the other was the perfect setting for The Railway Children in 1970.

They shot Yanks in Bradford, A Private Function, The Dresser. There have been at least two adaptations of Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights, shot on the very hills that inspired the novel. And the bleak 1980s sex comedy Rita, Sue and Bob Too was filmed all around Bradford’s most deprived areas, places lived in by the tragic playwright Andrea Dunbar who drew upon her own life for the you-have-to-laugh-or-you’ll-cry story of hope amid hopelessness.

Bradford has also had for a long time a major boon in the shape of what was once called the National Museum of Photography, Film and Television, then changed its name to the National Media Museum, and is now called the National Science and Media Museum. Owned by the Science Museum Group, it is a massively successful tourist attraction that encompasses all kinds of media, especially the internet. The museum had also for many years hosted the Bradford International Film Festival, which brought in big-name actors and filmmakers from across the world though, in a fairly ironic move, this was scaled down and then ultimately axed in the wake of the City of Film award.

Also, crucially, when Bradford put its bid in back in 2008 for the Unesco designation, it had a champion in the shape of director and producer Lord David Puttnam, along with homegrown talent Simon Beaufoy, who wrote the screenplay for Slumdog Millionaire, which that year scooped 11 Oscars, and Steve Abbott, who produced Brassed Off and A Fish Called Wanda.

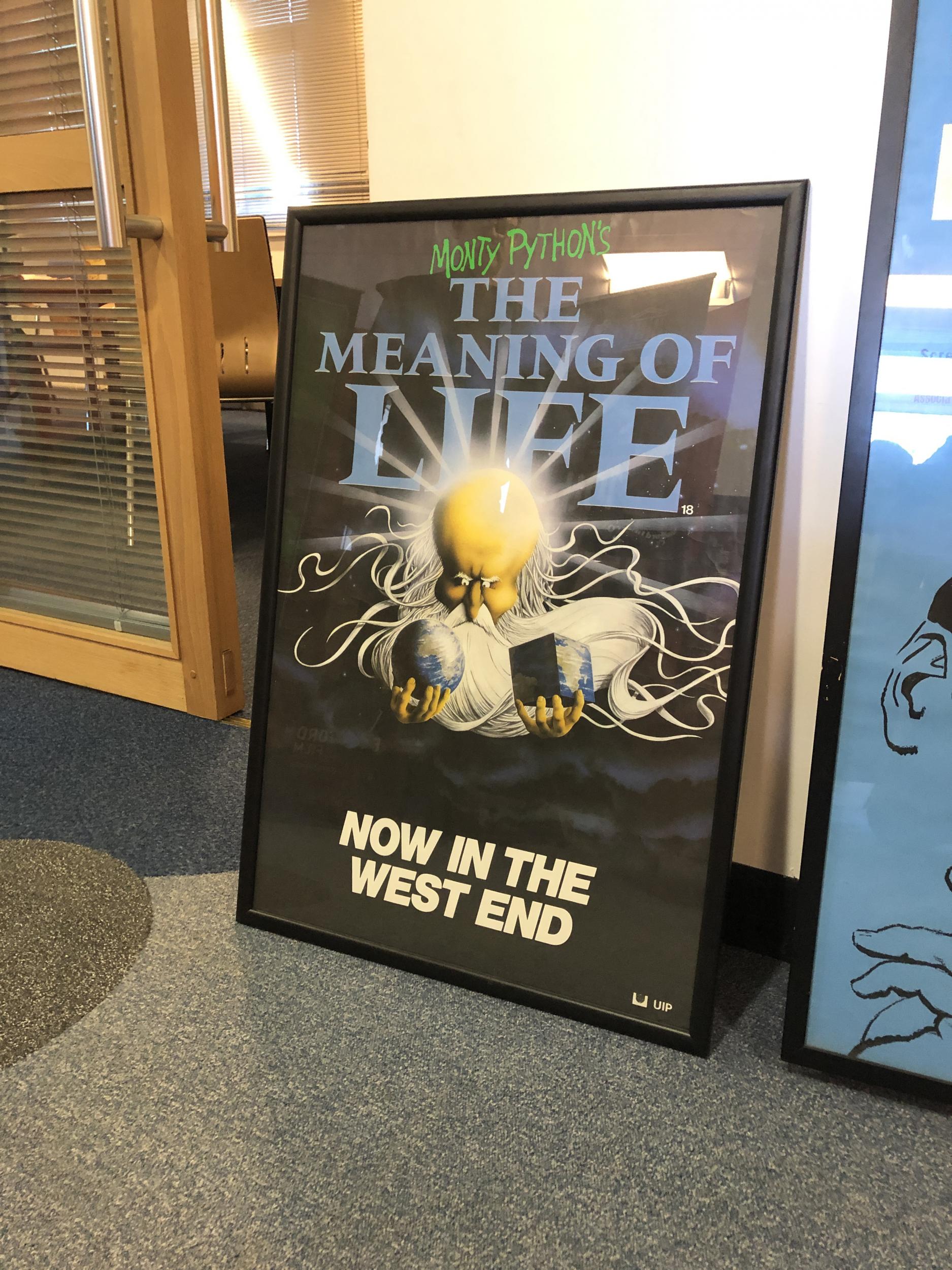

So, despite the naysayers, Bradford had a pretty good pedigree for winning the City of Film award. The question has to be asked, though, in true Monty Python style – and, fact fans, the musical number “Every Sperm is Sacred” in the Pythons’ 1983 movie The Meaning of Life was shot at the city’s Cartwright Hall – what has the Unesco City of Film ever done for us?

The answer is, actually, quite a lot as far as Bradford is concerned. It’s true that in the first couple of years after winning the designation, not a great deal seemed to happen. That was perhaps because while Unesco granted the appellation City of Film, it didn’t actually come with a penny of funding. And given the time it happened, there wasn’t exactly a lot of money swilling about in the local authority coffers to do a great deal about it.

David Wilson was brought in as director of the City of Film in 2011. He had previously worked for Bradford Council in a music development role. He was quite literally shown an empty office and wished good luck.

It would have been reasonably easy for Bradford to merely take the accolade, put up a few banners and maybe stick a logo on official notepaper (though Unesco can, of course, withdraw designations any time they think they aren’t deserved). But David Wilson knew that being City of Film could pay great dividends for Bradford.

“The first thing I did was reopen the film office,” he says. Ever since watching Billy Liar he had been acutely aware of the attraction of the district to filmmakers, and though there had been an active office in the 1980s, trying to bring film and TV producers to the area, that had fallen by the wayside. It immediately began to pay dividends, as the efforts of the City of Film team began to aggressively market Bradford to the industry and the industry began to take notice.

In 2018, 35 films and TV shows were shot in Bradford, including Peaky Blinders, which has shot most of its five seasons in the district, and ITV’s Victoria, which soon starts its next season. Movies such as the Maxine Peake film Funny Cow were shot in the city, as well as Ghost Stories, based on the hit stage show by Andy Nyman and Jeremy Dyson. Dyson, one quarter of The League of Gentlemen team, lives in Ilkley, part of the Bradford district. Official Secrets, a movie starring Keira Knightley, was filmed at Bradford’s imposing City Hall (in its bowels are old courtrooms that have proved a popular location for years, especially for Coronation Street), which goes on release later this year. And scenes in the forthcoming Downton Abbey movie have been filmed in Bradford.

The City of Film has even brought in many Bollywood productions to film in Bradford, most notably the hit movie Gold. Wilson is constantly trying to drive home to local businesses that they can capitalise massively on such productions. When the Gold team went to Bradford, they used local crew, offices and extras and booked the equivalent of 4,000 hotel overnight stays over a three-month period.

Bradford’s City of Film success has happened at the same time as the rise of Screen Yorkshire, one of the country’s most successful regional film offices that is responsible for encouraging investment in the Yorkshire and Humber region. Screen Yorkshire helps bring on local businesses working in the film and TV industries and markets the region to filmmakers from across the world. According to Office for National Statistics figures, the screen industries in Yorkshire and the Humber grew faster than anywhere else in the country, including London and the southeast, between 2009 and 2015.

In its 10th anniversary year, the Bradford City of Film is more successful than even Wilson could have envisaged when he first took over the running of the office. It now works out of a couple of rooms at the University of Bradford and is still not a massive operation – it comprises Wilson, two part-time staff and a couple of freelancers. Money is still not flowing in, but it’s testimony to the drive of the team, Wilson, especially, that it’s been such a success.

He says: “I’m proud of what we’ve achieved.” Wouldn’t it be nice to get more funding locally, though? He says carefully: “There has perhaps been a lack of understanding about what it is we do and what benefits it can bring.”

Bradford is now well and truly on the map for the TV and film industry, but that’s only a part of what the City of Film office does and perhaps, suggests Wilson, not necessarily the most important aspect.

“It’s nice to have all the red carpet stuff, of course it is,” he says. “But it was always the idea that City of Film would bring benefits to and give a voice to the local communities of Bradford.”

One of the big projects for 2019 is encouraging and facilitating the rise of community cinemas. Films are shown in village halls, community centres, churches, with perhaps surprising results. Wilson says: “Obviously we’re not trying to take people away from actual cinemas, but instead we’re bringing communities together. People who might have just nodded to each other on the street have become friends. And there’s a cross-generational benefit, younger and older people mixing. They watch films for entertainment, of course they do, but we also encourage them to show perhaps more challenging films, about which they can talk.”

It’s also about enabling communities to get involved and get their voices heard – recently the City of Film helped a group of Sudanese women who had fled the genocide in Darfur make a film about their lives in Bradford.

And there’s a strong focus on giving people from communities that might not historically have had much truck with the film industry the chance to realise their ambitions and recognise that there might well be a role for them in the world of film and TV.

“Most people just look at the names of the actors in the credits, maybe the producer or director on occasion,” says Wilson. “But there are hundreds of names in those closing credits of people involved in all aspects of making a film, from sound technology to catering, and we’re trying to get people to think about being a part of that. We want to inspire and empower them to think that yes, they could do that.”

Indeed, in September the City of Film presents the Get Smart Film Festival, dedicated to showing short films made entirely on smartphones, which they’re hoping as many people from the Bradford area get involved with as possible. “The technology to make films is literally in people’s hands now,” says Wilson. “We want to show them that anything is possible.”

Later this month Bradford hosts the International Film Education Symposium, welcoming experts from across the globe to talk about improving access to all strands of media, and in May Channel 4 brings its Diverse Festival – previously only held in London and Glasgow – to the city to thrash out how to make the industry more inclusive.

Anyone interested in a career in film or TV is in a very strong position; Channel 4 is moving up to neighbouring Leeds and Screen Yorkshire has recently opened a vast, dedicated sound-stage studio on a former airfield in the region. “I keep telling young people especially, this is their time to shine,” says Wilson.

Bradford is leading the world as the first City of Film – quite literally. Since 2009, Unesco has designated several further City of Films, including Santos in Brazil, Lodz in Poland, Busan in South Korea and Bristol here in the UK. The Bradford office has helped and advised and worked with all these places to achieve their designation.

It’s been a busy and often exhausting 10 years, but Wilson is already looking to the next decade and he’s no doubt where the opportunities lie. Wilson has been out to Qingdao – China’s Hollywood – three or four times already, and has forged close links with the Chinese film industry. So much so, that as a direct result of the close relationship, a Chinese adaptation of Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre is in the planning stages.

It’s very exciting times. Wilson says: “I’m hoping that this year really builds on all the progress we’ve made since 2009, and that we’ve put the measures in place to make Bradford City of Film sustainable for at least the next 10 years.”

For more information on the programme of 10th-anniversary events, go to bradfordcityoffilm.com

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments