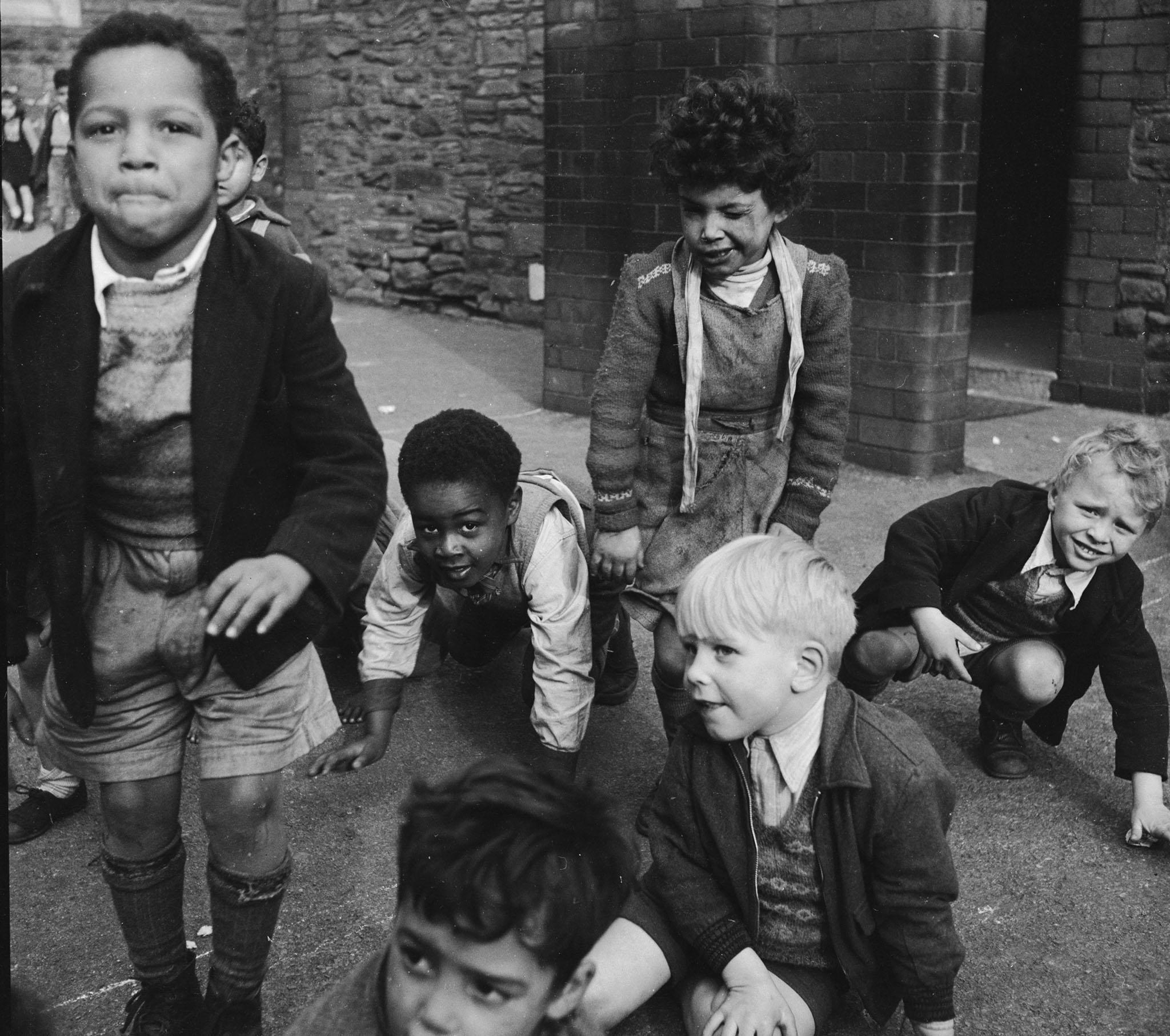

Live and let live: how migrants, through hard labour and integration, helped forge modern Birmingham

Emerging from the shadow of Enoch Powell’s dark rhetoric, Britain’s second city has a far more optimistic and inclusive outlook, writes Jon Bloomfield

Novelist Jonathan Coe has a better feel than most politicians and commentators for what is happening in our country.

Towards the end of his latest novel Middle England, one of his main characters, Sophie, says: “A more cheering thought rose up: the realisation that here, on this sunny day in April, the people of Birmingham – young people mainly – were going about their lives in happy and peaceful acceptance of precisely that melding of different cultures that Powell’s pinched, ungenerous mind had only been able to imagine leading to violence.”

These are turbulent times, but Coe captures the mixed, open and accepting spirit of modern Britain.

I’ve lived in Birmingham since the late 1970s. The contrast with the situation on my arrival is palpable. Then the city lived in the shadow of Enoch Powell. The city council had no black or Asian councillors; the National Front was a constant menace; police relations with ethnic minority communities were grim.

But changes were already underway: UB40 and The Specials were emerging as top-line, mixed-race bands playing new kinds of hybrid popular music; three black footballers – Cyrille Regis, Laurie Cunningham and Brendon Batson – were making the breakthrough at West Bromwich Albion; local Brummies were going in increasing numbers to Indian and Chinese restaurants across the city. My new book, Our City: Migrants and the Making of Modern Birmingham captures this transition in both the workplace and in wider society.

I interviewed fifty migrants whose families have come to the city since the Second World War. Their stories and the wider evolution of the city refute the doomsday diatribes of Powell and the continuing dire warnings of his acolytes on the nationalist right.

Instead, they illustrate not so much how migrants have assimilated to a pre-existing British culture but rather how they have contributed to an evolving, changing society.

The dirty, the dull, and the dangerous

The bulk of migrants have come here to work: at first in foundries, building sites and engineering plants.

David’s dad came from St Kitts in the Caribbean and moved to the UK in 1959. It was a difficult decision but he was looking for the opportunities that were here in the “mother country” as he called it. He knew he was coming to Birmingham before he left home. He arrived at Southampton and then came up to the Midlands. Already trained as a welder he found fabrication work easily in the construction industry. As a welder and contractor he worked all week and at factories over the weekends.

David’s mother was a cleaner at the central sorting office at the Mailbox. “My parents would be up and out before we went to school, both of them. That is what I remember very strongly growing up. I very rarely saw them even at weekends because my mum worked six days a week and my dad worked seven days a week. I only saw them in the evenings. My dad got home at 8am. I had to do the basics and learn to feed myself.”

They lived in inner city Nechells in a small two bedroom, old-fashioned place with a shared outside toilet and a tin bath hung up in the alleyway; a classic back-to-back before they moved to a council house in Bordesley Green where they had a front and back garden. David went to a secondary school in Nechells and then in 1979 aged sixteen he applied for and got offered two apprenticeship places, one with British Steel; the other with British Leyland. These were proper four-year craft apprenticeships in the traditional sense. David chose British Leyland. “I reckoned even at that stage that the automotive industry had better prospects than the steel industry.”

It was the right decision and now forty years later he’s a senior product engineer at Jaguar Land Rover.

Along with heavy industry, others came into the NHS. Most of the first generation’s sons and daughters, unlike David, tended to go into office work in the public or private sector; some set up their own business and many did 3D jobs – dirty, dull or dangerous – that no one else chooses to do.

Ashraf lives in a long line of red brick, narrow-fronted terraced houses. We sip tea in his living room, where the front door opens straight out onto the pavement. There are rows of streets here that stretch down to the main road that slices its way through inner city Sparkbrook. This used to be the heart of manufacturing Birmingham. The former Birmingham small arms factory, which in turn became the main centre of motorcycle production in the UK was based at the bottom of the road. Those days are long gone, along with most of the indigenous white working class that used to live in these Victorian terraces.

Today, the owner-occupied houses are full of people originating from the Indian sub-continent and their children, along with more recent arrivals from the Yemen and Somalia. A few Irish remain. Ashraf’s mother lives across the road from him, while two other brothers live further down the street.

Ashraf’s parents came from the Mirpur area of Pakistan. His dad arrived in the 1960s seeing the chance to earn money and do better for his family. That was the reason for emigrating. He saved money on housing by living like many other migrants in shared accommodation. As soon as the night shift finished, they would swap beds with the day shift. House sharing meant a lot of mattresses on the floor. In 1977 his mother got her visa and the family settled in Sparkbrook. His father got a job at the Fort Dunlop tyre plant where his manufacturing career continued until he was made redundant in the mid-1980s.

Ashraf was born in 1977 in Sparkbrook. He went to the local nursery, junior and secondary schools. His father died while he was still at school and he and his eight siblings were brought up alone by his mother. Education wasn’t the priority at the time among kids of his age unless the parents pushed you. His mother came from a rural, peasant background so there was no strong pressure on him to get on. He went to the local technical college but lasted only four months.

The first generation of post-war migrants to Britain had played their part in Britain’s post-war manufacturing revival. Ashraf’s dad worked in steel plants, foundries, brickworks and then a big tyre plant. The Thatcher era saw the wholesale demise of vast swathes of these manufacturing giants. From 1979 to 1984 Birmingham lost over 200,000 manufacturing jobs. The era of stable, steady, semi-skilled manufacturing jobs in large plants and factories drew to a rapid close.

Their sons and daughters either looked to the white-collar service sector for jobs, which usually required some examination qualifications or else they applied for the 3D jobs. With the assured, steady manufacturing jobs of his father’s era gone, Ashraf has had to find a series of 3D jobs in order to earn a living. He started working as a labourer, followed by a stint as a lacquer sprayer. He did some packing where there was decent money, followed by security work at the Pallasades shopping centre in town. He then had seven years as a mini-cab driver, which he liked but “was very, very flexible” on hours. A spell of unemployment followed. He now works as a delivery driver for Asda.

“It’s good. I enjoy it, being out, no one watching you. The wage isn’t brilliant, it’s about £7 an hour but it’s about how comfortable you are in your job. If you don’t enjoy the work, it’s not worth it. As long as I can pay my mortgage and provide for my children, money doesn’t have a massive significance. I am not ever going to be a millionaire but I can support my family. I have regular hours and a set contract, which are two of the advantages of working for a larger, established company.”

There have always been low paid and casual jobs in the economy. It is just that a more casualised , non-unionised, deregulated economy generates more of them. They are a growing feature of 21st century Britain. Carers, cleaners, cooks; van drivers, delivery drivers, taxi drivers; fruit pickers and food processors; packers and shelf stackers; waiters and washer-uppers; security men, porters, warehouse staff: many often working long hours, usually at the minimum wage, sometimes with irregular shift patterns and increasingly on zero hours contracts. These jobs are rife within and around the Birmingham area and they have been often filled by eastern Europeans.

Anita had no work in Gdynia, Poland, so she tried her luck in England. She flew into Stansted for a promised job in the pottery industry. However, the contact at the airport did not materialise and she realised she had been conned. She had friends already working in Birmingham, who told her to get a bus to the city. She arrived in Birmingham on Saturday and by Monday morning she had a job as a food processor, sorting potatoes arranged by a “temporary recruitment provider” based in Birmingham which offered Anita a job straight away. The workforce met in town and were taken by bus to a factory outside the city more than an hour away. The potatoes were being washed on a tray and the workforce then separated and sorted them.

“The working conditions were appalling. We were standing in water up to our ankles, or had water dripping down our backs or on our heads. We were wet all the time.”

There were no technical requirements for the job apart from stamina. As far as Anita could tell the main criteria for employment was that no one among the workforce spoke English, so they could barely communicate with each other. They normally worked twelve hours a day at the factory, sometimes fourteen, for six days a week. Anita got £1,000-1,200 a month, which was good money compared to what she was used to but amounted to a fraction of the legal minimum wage.

These 3D jobs remind us that large problems remain across the UK with rising inequality and insecurity, threatened to worsen with Brexit. But they should not lead us to forget the advances that have been made. Today, as Coe writes, the heart of Birmingham is mixed and inter-cultural. Walk around the Bull Ring shopping centre on a Saturday, you feel a modern, multi-ethnic city.

Samera’s dad came to Birmingham from Pakistan in 1960 and worked for years at GKN. She went into retail and is employed as a sales assistant in a big city centre store. With her straight black hair and brightly painted finger nails, as she stands by the counter taking the orders and chatting busily with the shoppers it’s obvious that she likes her work. She is happy with the pay, conditions and the people. There is a good mix of staff – black, white, Asian – who get along well. She has no career ambitions and doesn’t want to go into management. She is just pleased with her job as it is. Samera likes the mix of people who come into the city centre to shop.

“It’s good to have a mixture, I don’t like it when you just have one group of people. I like the city: there’s a real cosmopolitan mix.”

A culinary revolution

Nowhere is this more evident than in the migrant impact on Britain’s food culture. Half a century of migration has changed the country’s culinary landscape beyond all recognition. Birmingham has been at the epicentre of this culinary revolution. There are more than two hundred curry houses in the city: that’s one for every five thousand citizens. They are often clustered in the main Asian neighbourhoods but many more are scattered in the suburbs all around the city; some offering a cheap, simple meal, others catering for a more upmarket clientele, while the city created its distinctive hallmark with the Birmingham Balti, the original balti dish invented by Pakistanis living in Birmingham.

As the restaurant and takeaway sectors boomed, so did the need for knowledgeable suppliers of Chinese and south Asian food products.

Here is where Wing Yip scored. A migrant from Canton via Hong Kong, Wing arrived in the UK in 1959 with a few pounds in his pocket. Today, his oriental food grocery business stretches across four business sites in the UK: the main one in Birmingham is a 10-acre business park. The turnover exceeds £100m a year and he employs 370 staff. As he says simply: “We know the business.” Recognising the growing interest in food with the boom in TV shows and celebrity cookbooks, Wing’s stores are open to all keen to experiment with Chinese and oriental cooking. Today his stores stock more than 6,500 products.

This transformation of British food habits is one of the most significant features of the post-war migrant influx. It has opened the British palate to the tastes and delights of food from other cultures: it has excited people’s curiosity and their willingness to try something new and different. It is one of the most tangible benefits of post-war migration, transforming the eating habits of the majority of UK citizens. People have simply decided that rather than “meat and two veg”, they like Chinese and Indian restaurants and gone there in ever greater numbers.

Never has the British palate been so diverse and varied, nor have Brits been so willing to experiment with different food cultures. This has not been a road to assimilation but rather one of transformation: fifty years of entrepreneurial endeavour that have changed the taste buds of a city and a country.

A shift in social attitudes

The changing population mix has also shaped who we live with. In the mid 1980s, a British Social Attitudes survey showed 50 per cent of the public were against marriage across ethnic lines. The figure now stands at 15 per cent. If it’s good enough for Prince Harry, it’s good enough for most of us.

The 2011 Birmingham Census records nearly 25,000 households composed of whites and black Caribbeans; over 3,000 households of whites and black Africans; over 11,000 white and Asian households and 8,500 of other mixed backgrounds. In total, around 5 per cent of the city’s households are of mixed heritage. This trend was evident in the interviews I conducted with both Afro Caribbeans and Irish. It was weaker but, nevertheless, present among south Asians.

For the accountant Raj, born and brought up in Powell’s Wolverhampton, it is still important that the kids his children marry are Asian-Indian although he and his wife accept that there are more mixed relationships happening. In his relaxed, laid-back style Raj just says: “Look, this is our preference. We would be very disappointed but we would not disown them or anything.”

Among Muslims, whilst the picture is differentiated, the inhibitions and resistance are definitely stronger. There is a growing acceptance of change with regard to arranged marriage but for many, inter-marriage is a step too far. As Kalsoom expresses it: “To be honest with you, I wouldn’t be very happy about it. I would like them to marry Muslims. I know it is happening but religiously it is wrong. It is haram...”

It is hard to explain she says, as she chuckles and gives herself a rueful smile. She then admits that her eldest son is married to a non-Muslim, a Spanish Catholic whom she gets on well with. She would have preferred that he marry a Muslim girl but if he chooses her as his life partner and he gets on with her, then she is prepared to go along with it.

“I was hoping that as she sees the culture and studies it, she would become a Muslim but I don’t think that she should change her religion just for the sake of marriage. Deep inside, no matter how I try to be broad-minded, I wish that his family grow up as a Muslim, as a faith. And believing in one god.”

There is anguish and pain etched across her face as she explains the dilemma that she feels. Yet, at the same time she has the humanity to acknowledge that her daughter-in-law is a very good mother and wife and that she couldn’t hope for anyone better from the Muslim religion.

Others are less constrained.

Samera likes the freedom that being brought up in the UK offers and she makes full use of it. A single woman in her late 30s, she doesn’t wear a headscarf in the day, only putting one on when she goes to the mosque, as a sign of respect. She likes to wear jeans and T-shirts but doesn’t wear short skirts. But on men, she is clear: who she goes out with is her business and no one else’s.

In Birmingham, the dominant temperament remains one of live and let live. There are those of a fundamentalist disposition on social and religious as well as political issues but Raj captures the prevailing mood with his graphic observation,

“Of course, inter-marriage is happening. Like I said our preference is for our kids to marry Indians. But where inter-marriage does happen, we are not going to be Taliban about it.”

Hearing these stories and looking round the city it is clear that Powell’s thinking comes from another age. His old Wolverhampton seat is now held by a black female MP. In Birmingham more than a third of councillors are black or Asian. Last May, in Brexit-voting Wolverhampton, the football club won promotion to the Premier League with a squad composed of six Portuguese players, six Africans, several other Europeans and a handful of English players two of whom were black and one of Sikh Punjabi origin. The world has moved on.

Jon Bloomfield’s book, ‘Our City: Migrants and the Making of Modern Birmingham’ is published by Unbound. £18.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments