Behind China's $1 trillion plan to shake up the economic order

At the heart of China’s economic ambitions is the construction of a railway linking eight countries, but what effect will it have on the wider region?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Along the jungle-covered mountains of Laos, squads of Chinese engineers are drilling hundreds of tunnels and bridges to support a 260-mile railway, a $6bn (£4.7bn) project that will eventually connect eight Asian countries.

Chinese money is building power plants in Pakistan to address chronic electricity shortages, part of an expected $46bn worth of investment.

Chinese planners are mapping out train lines from Budapest to Belgrade, Serbia, providing another artery for Chinese goods flowing into Europe through a Chinese-owned port in Greece.

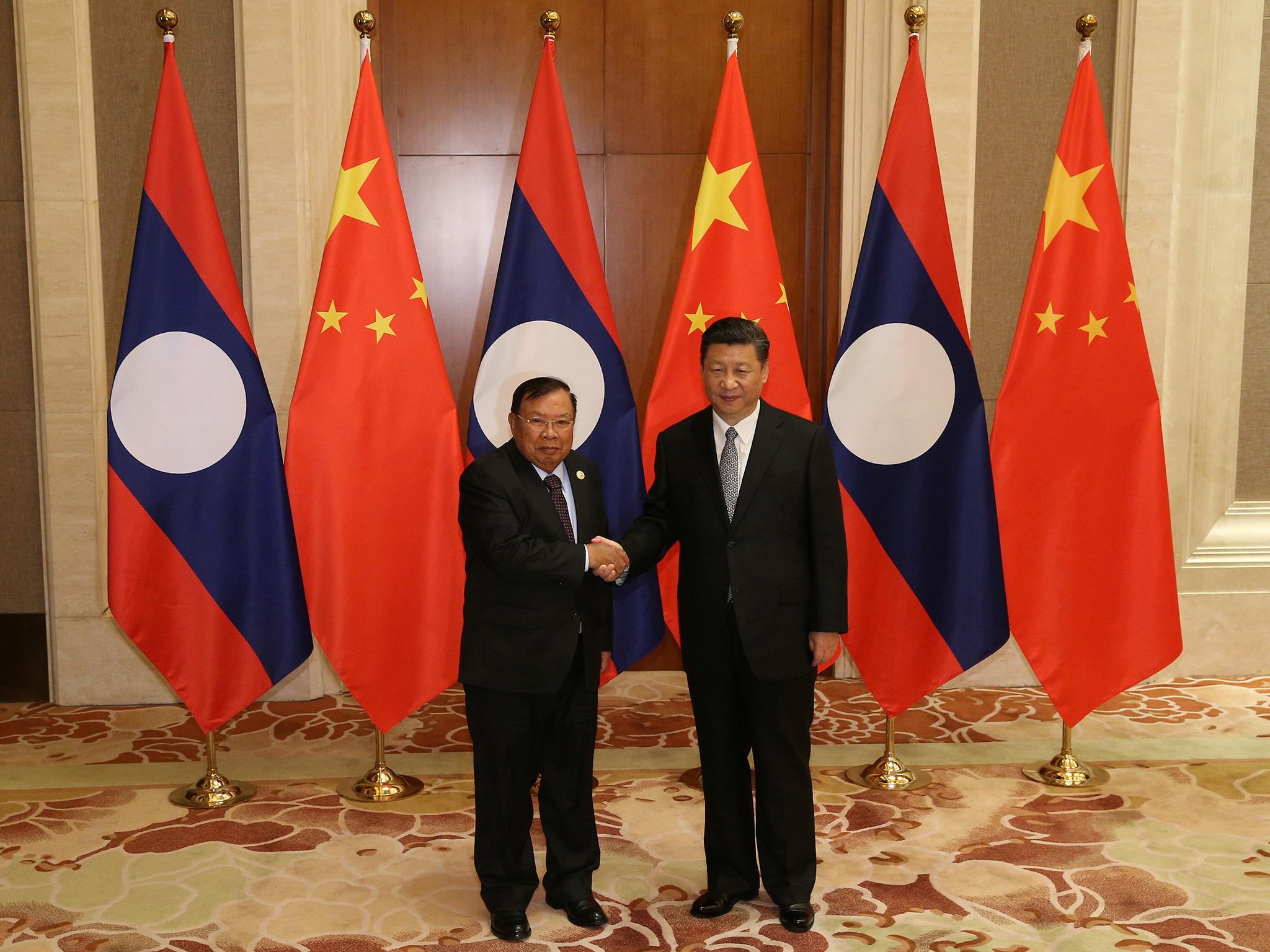

The massive infrastructure projects, along with hundreds of others across Asia, Africa and Europe, form the backbone of China’s ambitious economic and geopolitical agenda. President Xi Jinping of China is literally and figuratively forging ties, creating new markets for the country’s construction companies and exporting its model of state-led development in a quest to create deep economic connections and strong diplomatic relationships.

The initiative, called “One Belt, One Road”, looms on a scope and scale with little precedent in modern history, promising more than $1 trillion in infrastructure and spanning more than 60 countries. To celebrate China’s new global influence, Xi is gathering dozens of state leaders, including President Vladimir Putin of Russia, in Beijing on Sunday.

It is global commerce on China’s terms. Xi is aiming to use China’s wealth and industrial know-how to create a new kind of globalisation that will dispense with the rules of the ageing Western-dominated institutions. The goal is to refashion the global economic order, drawing countries and companies more tightly into China’s orbit.

The projects inherently serve China’s economic interests. With growth slowing at home, China is producing more steel, cement and machinery than the country needs. So Xi is looking to the rest of the world, particularly developing countries, to keep its economic engine going.

“President Xi believes this is a long-term plan that will involve the current and future generations to propel Chinese and global economic growth,” says Cao Wenlian, director general of the International Cooperation Centre of the National Development and Reform Commission, a group dedicated to the initiative. “The plan is to lead the news globalisation 2.0.”

Xi is rolling out a more audacious version of the Marshall Plan, America’s postwar reconstruction effort. Back then, the United States extended vast amounts of aid to secure alliances in Europe. China is deploying hundreds of billions of dollars of state-backed loans in the hope of winning new friends around the world, this time without requiring military obligations.

Xi’s plan stands in stark contrast to President Trump and his “America First” mantra. The Trump administration walked away from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, the American-led trade pact that was envisioned as a buttress against China’s growing influence.

“Pursuing protectionism is just like locking oneself in a dark room,” Xi told business leaders at the World Economic Forum in January.

As head of the Communist Party, Xi is promoting global leadership in China’s own image, emphasising economic efficiency and government intervention. And China is corralling all manner of infrastructure projects under the plan’s broad umbrella, without necessarily ponying up the funds.

China is moving so fast and thinking so big that it is willing to make short-term missteps for what it calculates to be long-term gains. Even financially dubious projects in corruption-ridden countries like Pakistan and Kenya make sense for military and diplomatic reasons.

The United States and many of its major European and Asian allies have taken a cautious approach to the project, leery of bending to China’s strategic goals. Some, like Australia, have rebuffed Beijing’s requests to sign up for the plan. Despite projects on its turf, India is uneasy because Chinese-built roads will run through disputed territory in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir.

But it is impossible for any foreign leader, multinational executive or international banker to ignore China’s push to remake global trade.

Germany’s minister of economics and energy, Brigitte Zypries, plans to attend the meeting in Beijing. Western industrial giants like General Electric and Siemens are coming, as they look for lucrative contracts and try to stay in China’s good graces.

The Trump administration just upgraded its participation.

Originally, it planned to send a Commerce Department official, Eric Branstad, the son of the incoming American ambassador to Beijing, Terry Branstad. Now, Matthew Pottinger, senior director for Asia at the National Security Council, will attend instead – a signal that the White House is enhancing its warm relationship with Xi by honouring his favourite endeavour with the presence of a top official.

Influence via infrastructure

As the sun beat down on Chinese workers driving bulldozers, four huge tractor-trailers rolled into a storage area here in Vang Vieng, a difficult three-hour drive over potholed roads from the capital, Vientiane. They each carried massive coils of steel wire.

Half a mile away, a Chinese cement mixing plant with four bays glistened in the sun. Nearby, along a newly laid road, another Chinese factory was providing cement for tunnel construction.

Nearly everything for the Laos project is made in China. Almost all the labour force is Chinese. At the peak of construction, there will be an estimated 100,000 Chinese workers.

When Xi announced the “One Belt, One Road” plan in September 2013, it was clear that Beijing needed to do something for the industries that had succeeded in building China’s new cities, railways and roads – state-led investment that turned it into an economic powerhouse. China did not have a lot left to build, and growth started to sputter.

Along with the economic boost, tiny Laos, a landlocked country with six million people, is a linchpin in Beijing’s strategy to chip away at American power in Southeast Asia. After Trump abandoned the Trans-Pacific Partnership in January, American influence in the region is seen to be waning. The rail line through Laos would provide a link to countries that China wants to bring firmly into its fold.

Each nation in Xi’s plan brings its own strategic advantages.

The power plants in Pakistan, as well as upgrades to a major highway and a $1bn port expansion, are a political bulwark. By prompting growth in Pakistan, China wants to blunt the spread of Pakistan’s terrorists across the border into the Xinjiang region, where a restive Muslim population of Uighurs resides. It has military benefits, providing China’s navy future access to a remote port at Gwadar managed by a state-backed Chinese company with a 40-year contract.

Many countries in the program have serious needs. The Asian Development Bank estimated that emerging Asian economies need $1.7 trillion per year in infrastructure to maintain growth, tackle poverty and respond to climate change.

In Kenya, China is upgrading a railway from the port of Mombasa to Nairobi that will make it easier to get Chinese goods into the country. The Kenyan government had been unable to persuade others to do the job, whereas China has been transforming crumbling infrastructure in Africa for more than a decade.

The rail line, which is set to start running next month, is the first to be built to Chinese standards outside China. The country will benefit for years from maintenance contracts.

“China’s Belt and Road initiative is starting to deliver useful infrastructure, bringing new trade routes and better connectivity to Asia and Europe,” says Tom Miller, author of China’s Asian Dream: Empire Building Along the New Silk Road. “But Xi will struggle to persuade skeptical countries that the initiative is not a smokescreen for strategic control.”

Calculating the risks

Although Chinese engineers just started arriving in this tourist town several months ago, they have started punching three tunnels into mountains that slope down to roiling river water. They are in a race to get as much done as possible before the monsoon rains next month slow down work.

It is a fast start to a much-delayed program that may bring only limited benefits to the agrarian country.

For years, Laos and China sparred over financing. With the cost running at nearly $6bn, officials in Laos wondered how they would afford their share. The country’s output is just $12bn annually. A feasibility study by a Chinese company said the railway would lose money for the first 11 years.

Such friction is characteristic.

In Indonesia, construction of a high-speed railway between Jakarta and Bandung finally began last month after arguments over land acquisition. In Thailand, the government is demanding better terms for a vital railway.

China’s outlays for the plan so far have been modest: Only $50bn has been spent, an “extremely small” amount relative to China’s domestic investment program, says Nicholas R Lardy, a China specialist at the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington.

Even China’s good friends so far are left wanting. Xi attended a groundbreaking ceremony in 2014 in Tajikistan for a gas pipeline, but the project stalled after Beijing’s demand waned.

Putin will be at the centre of the Beijing conference. While two companies owned by one of his closest friends, Gennady Timchenko, have benefited from projects, there has not been much else for Russia.

“Russia’s elites’ high expectations regarding Belt and Road have gone through a severe reality check, and now oligarchs and officials are skeptical about practical results,” says Alexander Gabuev, senior associate at the Carnegie Centre in Moscow.

China is making calculations that the benefits will outweigh the risks.

The investments could complicate Beijing’s effort to stem the exodus of capital outflow that have been weighing on the economy. The cost could also come back to haunt China, whose banks are being pressed to lend to projects that they find less than desirable. By some estimates, over half the countries that have accepted Belt and Road projects have credit ratings below investment grade.

“A major constraint in investor enthusiasm,” says Eswar Prasad, professor of trade policy at Cornell University, “is that many countries in the Central Asian region, where the initial thrust of the initiative is focused, suffer from weak and unstable economies, poor public governance, political stability and corruption.”

Laos is one of the risky partners. The Communist government is a longstanding friend of China. But fearing China’s domination, Laos is casting around for other friends as well, including China’s regional rivals Japan and Vietnam.

After five years of negotiations over the rail line, Laos finally got a better deal. Laos has an $800m loan from China’s Export-Import Bank and agreed to form a joint venture with China that will borrow much of the rest.

Still, Laos faces a huge debt burden. The International Monetary Fund warned this year that the country’s reserves stood at two months of prospective imports of goods and services. It also expressed concerns that public debt could rise to around 70 per cent of the economy.

As construction gathers steam, nearby communities are starting to rumble.

Farmers are balking at giving up their land. Some members of the national assembly have raised questions about property rights.

At Miss Mai’s Noodle Shop here, a customer, Mr Sipaseuth, pondered the project over a glass of icy Beer Lao.

In the past, he says, the government had promised $10 for an acre of land worth about $100. “But then they never paid it,” he says.

Was the rail project good for Laos?

“We need civilisation. Laos is very poor, very underdeveloped,” he says. “But how many Chinese will come here? Too many is not a good idea.”

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments