Urban beekeeping is not saving our precious pollinators – it’s killing them

After massive population declines, the honey bee has become a symbol of conservation. But that doesn’t mean we should prioritise it over other species, says Rebecca Bosy. Overpopulating city ecosystems could be disastrous for biodiversity, and, in turn, the survival of the human race

Finally, spring has sprung. Soon, bees will be buzzing about, navigating flowery meadows and city streets alike, crash-landing into nutritious blossoms. However, despite relentless “Save the Bees” campaigns, danger is still looming for these furry little creatures – but for different reasons than you might think.

For years, urban beekeeping has been on the rise in big cities such as London. The introduction of more pollinators to metropolitan areas has been hailed by many as an environmental saviour. But this supposedly eco-friendly practice might bring more harm than good in the long run, as it threatens the myriad of insects already living in – and depending on – urban areas.

New research shows that beekeeping reduces the diversity of wild pollinators, which negatively impacts plant-pollinator networks, meaning that introducing huge numbers of honey bees into cities is not the solution we have been searching for. Honey bees are among the only pollinators that make enough honey for human consumption, as they do not hibernate but remain active all winter. Unfortunately, this means that these bees collect nectar and pollen from more plants than any other native species, which creates fierce competition for food. In areas where flowers are already in short supply, this is disastrous for biodiversity, and could result in native pollinators starving.

There are around 20,000 different bee species globally, and 250 in the UK alone. Like all pollinators, bees are crucial in any ecosystem, and it’s estimated that around a third of the food we eat each day relies on pollination by bees and other insects, such as butterflies, ladybugs, beetles, flies and dragonflies. Even lizards, birds and bats contribute to this process, along with wind and water.

However, due to habitation loss and the use of pesticides in agriculture, coupled with urban expansion, parasites, diseases and climate change, the situation has become what Darryl Cox, senior science and policy officer at the Bumblebee Conservation Trust, calls a “cocktail of catastrophe”.

Since the 1940s, two bumblebee species have gone extinct in the UK, while seven more have seen their populations drastically reduced. While it’s incredibly challenging to track and measure pollinators, the trust has recorded bumblebees since 2006, and, according to Cox, “half of British bumblebees are becoming less abundant”. This is a dangerous development, as bumblebees are often classed as a “key stone species”, meaning that they help hold together complex food chains.

If we lost the bumblebees, Cox says, many plants would struggle to reproduce, meaning fewer fruits and seeds, which in turn means less food for other animals, including humans.

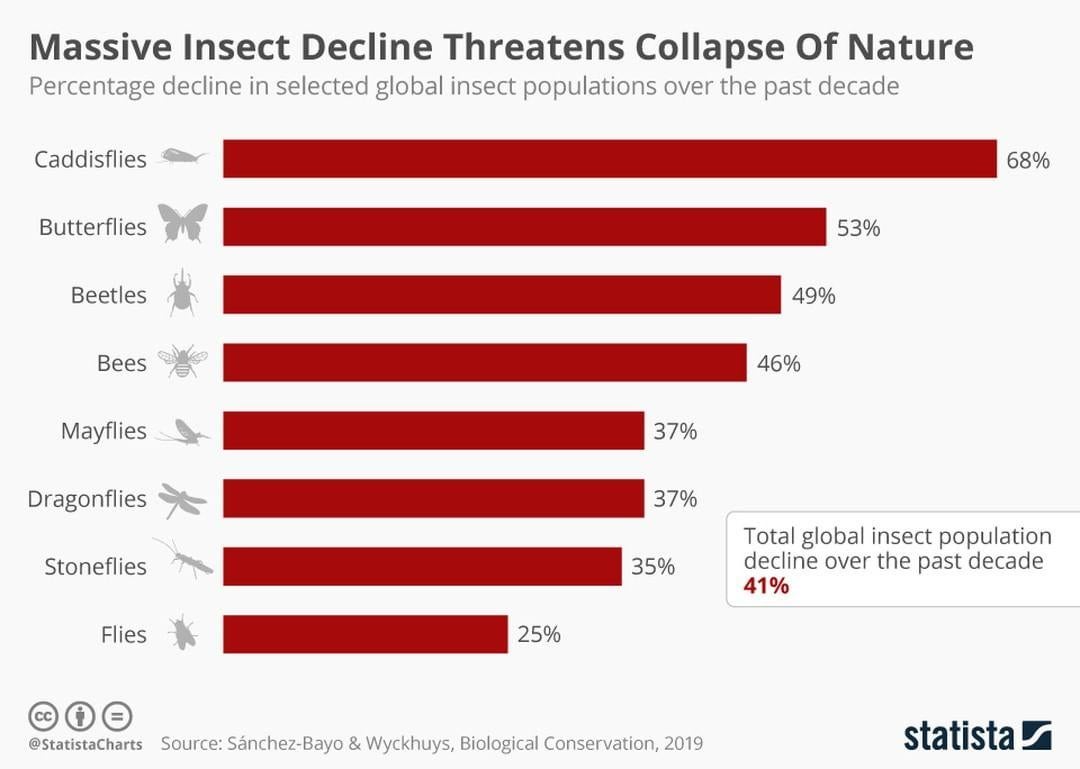

These numbers are worrying, and it’s not just the bumblebees that are struggling. The general pollinator population has been declining rapidly in recent years, and studies have found that some areas have experienced a dramatic 75 per cent decline in insect populations.

Bees are critical pollinators; they pollinate 70 of the around 100 crop species that feed 90 per cent of the world. Simply put, without pollinators we would lose many of our staple foods, such as apples, broccoli, melons, almonds and berries, and many plants and flowers could eventually become extinct. In addition, the animals that are dependent on either these plants or on insects as a source of food could end up struggling as well.

If we allow this decline to continue, the bee population might eventually dwindle to nothingness. Many people have established hives on London rooftops – while this does contribute to a greater number of bees, and in turn a greater number of pollinated plants, it doesn’t help wild bees or other pollinator species. In fact, the influx of domesticated honey bees speeds up their already speedy decline.

Cox states that while honey bees are important pollinators too, they are – unlike wild bees – “essentially livestock, and as with any commercial practice, there are risks to the environment which need to be considered”.

Avid campaigning on behalf of bees has made the honey bee in particular a symbol of conservation – you can buy honeycomb jewellery or beeswax cosmetics from many well-meaning companies that want to make a difference.

This is all good for the bee, but it means that native diversity in nature is hardly acknowledged or considered. We cannot forget the flies, the wasps or the moths, that are also important, not only to ecosystems and biodiversity, but also in pollination of plants and flowers. Unfortunately, “Save the Flies and Moths” doesn’t quite have the same impact as “Save the Bees” or “Save the Butterflies”, and a necklace adorned with a brass fly would probably not be a bestseller.

Without flies, we might not have carrots or chocolate. Without wasps, insect pests could overrun our gardens. Without moths, birds and bats lose an important source of food. In fact, the overall number of moths has decreased by almost 30 per cent since 1968, and it’s speculated that this has contributed to the decline of bats and cuckoo birds in farmlands. Every ecosystem is a work of art, and a drop in biodiversity will have dangerous consequences for the entire system.

According to a new UN-backed three-year study, loss of biodiversity is just as important as climate change. After all, when humans disturb the harmony and balance in nature, the repercussions tend to be enormous.

In urban societies, the very foundations of the cities are what makes it hard for insects to thrive. Glass, steel and concrete does not make a happy bee. Shrinking green spaces, and the decrease of bee-friendly plants makes it hard to collect enough pollen, even if pollinators are exceptionally good at locating the right flowers.

Jonas Geldmann, research fellow at the University of Cambridge’s Department of Zoology, says he doesn’t see any direct advantages to urban honey beekeeping.

“Keeping honey bees in cities could be a gateway to a better understanding of the need to make city parks wilder and to make people more aware about the plight of pollinators and insects,” he says, “but it’s a bit of a shame if that is what it takes. Such important causes shouldn’t have to rely on people keeping bees in cities, which at best has no consequences to the cause and at worst negatively affects it.”

He says that urban settings are important for many insect species that find refuge there, away from the harsher environment of the agricultural landscape. “As there really is no need to boost pollination, it would be a shame if honeybees jeopardise the wild pollinators in cities.”

Gail MacInnis, a PhD entomology candidate and research assistant at McGill University, says that while the biggest threats in both urban and rural areas is habitat loss, urban beekeeping is an increasing threat to urban bee diversity.

“You have to remember that honey bees live in colonies of up to 80,000 individual bees,” she says. “All these bees are competing for the same resources. If the floral resources in cities are limited to resident gardens and parks, and there is an influx of thousands and thousands of honey bees, the food sources for other bees are going to be depleted pretty quickly.”

While the domesticated European honey bee is a supergeneralist bee – meaning they visit any flowering plant species – other wild bees, such as bumblebees, are specialist and will only visit certain host plants when collecting nectar and pollen.

Because of the monoculture in our agricultural landscape, many specialist bees struggle to find suitable flowers and plants. There are now larger fields with fewer hedgerows and fewer wildflower meadows; the opposite of what a diverse pollinator population requires.

The honey bees might have their hives, but most wild pollinators are solitary and nest in the soil, in trees and in dead wood, which is hard to come by in agriculture where the soil is frequently tilled. This means that urban areas can serve as a refuge for many wild pollinator species, and that cities can actually be higher in diversity than agricultural areas.

There is little regulation pertaining to how many honey bee hives can be brought into a city, and MacInnis says that beekeeping companies can take advantage of this “by selling bee hives to residents under the guise of ‘saving the bees’”.

She thinks city officials need to be more proactive and get an awareness of the negative impacts honey bees can have on the local, native bee species already inhabiting the cities.

MacInnis wants to dispel the myth that honey bees are somehow an endangered species, as, on a global scale, honey bee populations have been increasing.

“In many areas the European honey bee are introduced, and they are managed by humans. They’re akin to livestock. There has been a great analogy going around that I really like: ‘Beekeeping as a way to save the bees, is like farming chickens to save the birds.’”

While the honey bees do have their place in crop pollination, they “are an invasive species in most places, and introducing them in high-densities in cities and natural areas is definitely not environmentally friendly or ecologically responsible”.

There also seems to be a perception of honey bees as more effective pollinators, but recent studies actually show that wild bees trumps honey bees in pollination, yielding larger strawberry crops.

“Our wild, native pollinators deserve much more attention than the honey bee as they are largely unmanaged and are much more vulnerable to decline.”

She also says that domesticated honey bees are necessary in modern agricultural productions, as these landscapes are almost devoid of wild pollinator habitat, and those that remain are often not abundant enough to provide full pollination to such large fields. However, she says, “honey bees are having a hard time keeping up with continually increasing pollinator-dependent cropland. If honey bee mortality continues to increase due to parasites, pesticides, poor nutrition and habitat loss, costs of beekeeping are only going to keep increasing. This may one day become an unsustainable operation for the beekeeper.”

Instead, she suggests a more sustainable way of pollinating crops: encourage less giant monoculture fields, and start providing more habitat and floral resources for wild pollinators on farms. This way, they can recolonise the areas and eventually provide pollination services in a more natural and sustainable way.

If such habitat is provided and maintained, wild pollinators could provide a cheaper, but more long-term solution for farmers in need of pollination. While there would be an initial cost of implementing habitat and resources, it would cost much less than renting honey bee hives each year.

Jessica Forrest, assistant professor at the University of Ottawa’s Department of Biology, says it’s important to note that managed honey bees get help from humans that other bees don’t, in the form of housing, parasite control, and even food subsidies. This helps keep their numbers up, potentially much higher than what the ecosystem would naturally support.

On the other hand, managed honey bees do face stresses that wild bees don’t, largely because of the way humans treat them – trucking them around for pollination and exposing them to pesticides, including the pesticides that are necessary to keep their parasites under control.

Forrest agrees with the dangers of urban beekeeping. “Honey beekeeping almost certainly has a negative impact on many species of wild bees. One study recently estimated that a single honey bee hive in a single summer gathers as much pollen as would be required to produce 100,000 individuals of a typical solitary bee species!”

“Different species pollinate different kinds of plants, so having a variety of pollinators in an ecosystem makes it more likely that all plants can get pollinated. Honey bees are fine pollinators of apple and almond blossoms, but they are not effective pollinators of tomatoes or peppers, which need to be buzz-pollinated—something bumblebees can do, but honey bees can’t.”

She says it’s extremely risky for wild plant pollination to be dependent on honey bees alone. If honey bees get wiped out, for instance as a result of the many diseases and parasites that threaten them, or because of environmental changes, we won’t have wild pollinators to fall back on. “It’s always risky to be reliant on a single species for anything!”

Jonas Geldmann says that the insect crisis is too severe for policymakers and individuals not to take action. As an individual, you can plant native flowers – especially ones that bloom in the early spring or late summer – keep your garden wild by mowing the lawn less often or not at all, advocate for more wild parks in cities and encourage councils to use less pesticides.

However, he says that the biggest responsibility falls on the policymakers. “The single most important step for protecting insects is to set aside land dedicated and managed exclusively for nature. This will require more than what any individual can do on their own. This is because what these rare and threatened pollinators need most is large, old, well-connected areas where natural processes can occur.”

Want to see how bee-friendly your own garden is? Check out the Bumblebee Conservation Trust, which recently launched a useful free online tool called Bee Kind to help people make the right choices for bees in their gardens

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments