Beach Boys blues: Is our love affair with the beach over?

Brian Wilson and his surf band had a brand of wistful melancholic yearning integral to songs like ‘Wouldn’t it be nice’ and ‘I’m waiting for the day’ – but will the day they were dreaming of ever come? Andy Martin takes a look at the myth of the beach and how it has eroded with the sands of time

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It was good while it lasted. Our love affair with the beach. It endured over hundreds of years and now it feels like it’s coming to an end. Personally, I blame Captain Cook. He died on a beach in Hawaii in 1779, so I guess the Hawaiians blamed him too. They took his name just a little too literally. But maybe we should have learned from his downfall. Cook – and his French counterpart Bougainville – imported the idea of the beach as a Polynesian paradise with palm trees back in the second half of the eighteenth century and we have been struggling to live up to that fantasy ever since. The death of Cook was like a blood sacrifice to set up a new religion.

It makes a sedate appearance in Impressionist paintings of Normandy (Monet’s “On the Beach at Trouville”, for example) and then more erotically in Gauguin’s naked Tahiti paintings. Then it takes off again with the twentieth-century renaissance of surfing and hedonism. In anthropology the myth of the beach took shape in Margaret Mead’s Coming of Age in Samoa (1929) which depicts sexually permissive beach girls disporting themselves, and it gets injected into the mainstream via the Beach Boys and the music of Brian Wilson in the sixties.

According to Freud, the beach was the natural habitat of the pleasure principle run riot. The id on holiday. Or on surfari. And it was still there, en masse, strutting the multitudinous sands from Huntington Beach to Santa Monica, last weekend, in shorts and t-shirt, with a surfboard under one arm. I think I first began to have doubts about my faith two or three decades ago when I paddled out at Malibu one April or May and got the shock of my life when it turned out to be as cold as Scotland. Saint Tropez, I knew, from personal experience, never quite lived up to the utopian hype. But surely a West Coast road trip in the middle of August would not let me down? Even if it was a Cadillac and not a convertible (it was all they had at Rent-a-Car). “If everybody had an ocean,” as the Beach Boys once sang, “Across the USA, Then everybody’d be surfin’ Like Californ-i-a.”

There is a photograph of Jean-Paul Sartre stalking across the sands of a beach somewhere in Latvia back in the Fifties. He is wearing all his clothes and an overcoat and is tilted forwards at an angle to the universe. To hell, he appears to be saying, with all this hedonism nonsense. All you can look forward to is sand in your shoes and sunburn. His rival and antagonist Albert Camus, who hailed from the southern Mediterranean, was the great bard of the beach. And he had a better tan. Swimming is the high point in The Plague, for example, and he speaks in his Carnets of the water washing away all the sins of the world, like some kind of baptism. Sartre was heaping scorn on all that beachside bewitchment. But even he allowed (in Being and Nothingness) that surfing - “sliding on water” – was superior to skiing, because it left no trace, no track, since the wave folded over and erased the surfer’s path, and therefore was pure and unadulterated “being”.

The lyrical side of existentialism has been picked up in Aaron James’s Surfing with Sartre: An Aquatic Inquiry into a Life of Meaning, published this month, in which he sees baggy shorts and a board as a decent and credible post-industrial anti-capitalist alternative to workaholic life on land. The surfer thus becomes a “new model of civic virtue”, replacing the Protestant work ethic with more laid-back, eco-friendlier, recreational exploits.

I agree with James that capitalism runs dry where the sand begins. You can’t build castles on sand. There are plenty of examples of Californian court cases where beach lovers (around Malibu, for example) have sued landowners for blocking their right of way and won. The beach is probably as near to sunny socialism as you can get in America. The sand is not a commodity but is collectively owned and free and available to all. But, paddling just a little way out, as Sartre himself asks in the dark pages of Nausea, “What is lurking beneath the surface?” Is it really all fraternity and innocent fun?

Even the Beach Boys don’t say that. In fact, especially the Beach Boys. Brian Wilson, their main inspiration and force, became a depressive, schizophrenic drug-addict, and the lyrics of their classic songs give some subtle pointers to the formation of this state of mind. There is a suggestion, in “Wouldn’t It Be Nice”, of Aaron James-style mystic well-being: “Wouldn’t it be nice to live together in the kind of world where we belong”. But the song effectively postpones all the good vibrations, locating them in some hazy, indeterminate future. Everything you really want is in the conditional tense. And perhaps the very idea of pouring it all into a song is self-defeating: “You know the more we talk about it, It only makes it worse to live without it.”

There may be a hint of a suicidal tendency in “God Only Knows”: “If you should ever leave me, Though life would still go on believe me, The world could show nothing to me, So what good would living do me?” At the very least there is disillusionment: “I’m getting bugged driving up and down the same old strip. I gotta find a new place where the kids are hip.” (“I Get Around”). There is a note of hope, in “I’m Waiting for the Day”, but it is mixed with uncertainty: “I came along when he broke your heart… I’m waiting for the day when you can love again.” Love belongs firmly in the past or the future, it cannot be now.

The beach is a liminal state, intermediate between the concrete and tarmac (and little deuce coupe) of solid land and the rigours and hazards of the ocean wave. “Sloop John B” is a bad luck story. The refrain, let us recall, is, “I feel so broke up, I want to go home.” This is no hymn to the sea. Just in case you missed the point, “This is the worst trip I’ve ever been on.”

A less familiar song, “Beaches in Mind” is explicit about the discrepancy between “the dream” and the reality – “I’ve been trying to make [it] come true.” Again the future tense predominates: “It’ll just be me and you… We’ll find a place in the sun Where everyone can have fun.” There is nothing sadder than that line. The Beach Boys (and Wilson in particular) suffer from nostalgia for the future. What seems difficult to the point of impossible is achieving a sense of living and being in the present moment. The Wilson oeuvre, taken as a whole, sounds like a critique of a metaphysics of presence which may be (both in the affirmation and the repudiation) the distinctive note of sixties utopianism. There is a Waiting for Godot-esque mood in all the talk of how good it is going to be at some point further down the road: “We’ll all be planning out a route We’re going to take real soon. We’re waxing down our surfboards, We can’t wait for June.”

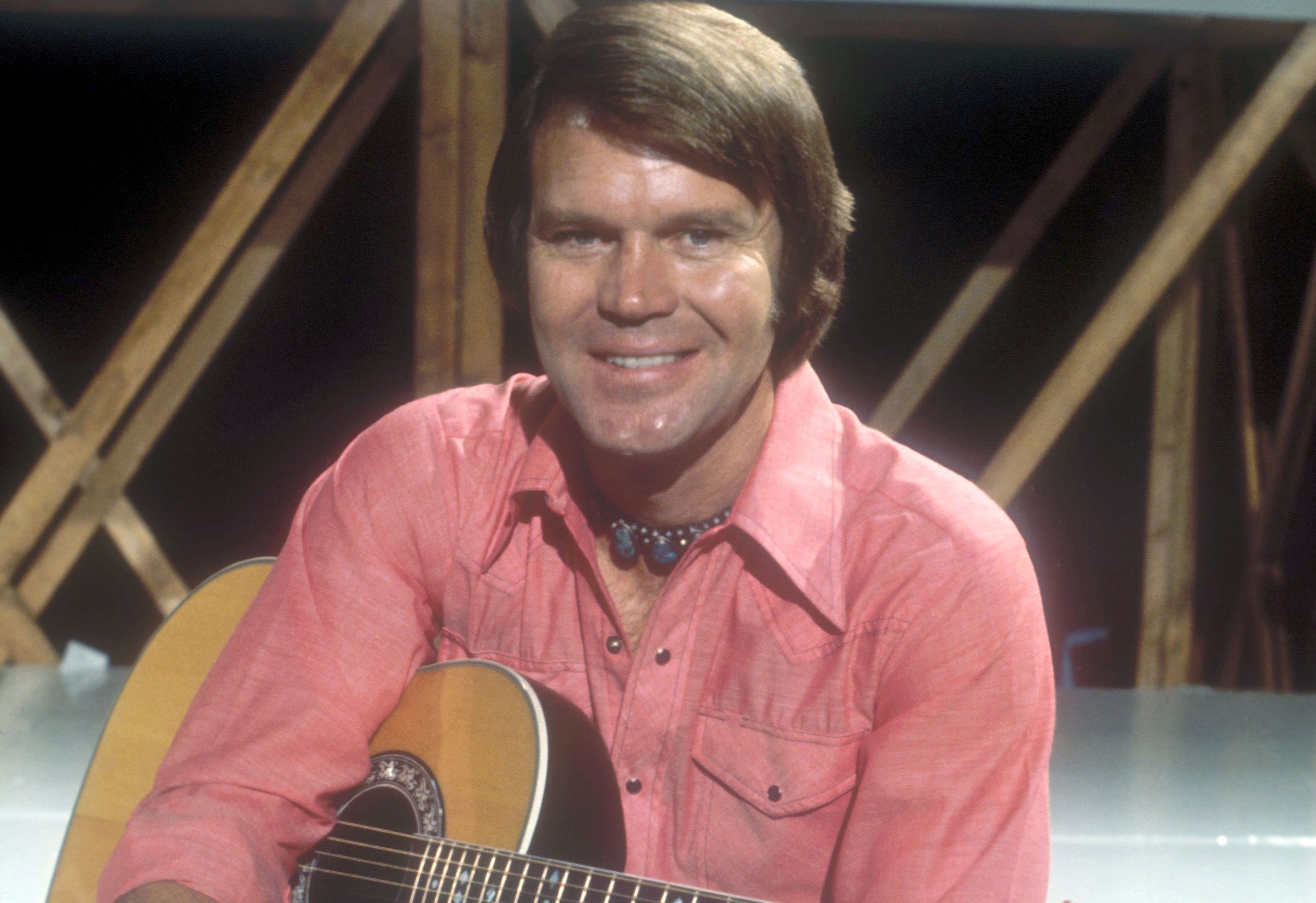

Perhaps Brian Wilson was preoccupied above all by inauthenticity. The “Noble Surfer” is ‘somethin’ you and I would like to be” but cannot be. “That’s Not Me.” It wasn’t just that the Beach Boys couldn’t surf. This was being on the mode of not-being (as the existentialists say). The conflict between what they were supposed to be and what they really were became increasingly unbearable to someone like Wilson. Drugs came along to fill the void. I learned only on the death last week of Glen Campbell that he had played guitar on Pet Sounds and gone on tour with the band. And his brand of wistful, melancholic yearning is integral to the Beach Boys mentality. Think of “Peggy Sue”, for example: “how my heart yearns for you.” Presumably unrequited.

I have recently been studying the life and surprising death of a British-American beach boy who was a fugitive from the English class system. Viscount Edward Deerhurst, universally known as Ted, brought up partly in Santa Monica by his American mother Mimi, wanted desperately not to become the next Earl of Coventry. He aspired to the solidarity and classlessness of the beach and dedicated himself to helping blind and disabled kids to surf with his “Excalibur” charity work (he said he identified with the disabled) and tried to make a living out of pro surfing. But just like Captain Cook he died in Hawaii. He said that he didn’t want to grow up and he got his wish, dying shortly after his fortieth birthday in 1997. In a bathtub, in Turtle Bay, on the North Shore of Oahu. The exact circumstances of his death are murky and mysterious, but irrespective of questions to do with natural causes or foul play and his plans to go into the law, I can’t help but feel that he died afflicted by disappointment.

It wasn’t just his dream of the “perfect wave” and (his own fond idea) the “perfect woman” that were bound to run into a reef. He wanted to be “one of the boys” and attain some kind of union with his immediate environment, but he discovered that the beach was the unforgiving realm of a reborn feudalism. Like the lonely swain of some courtly romance, he revered and looked up to a new dominant semi-sublime class of “living legends” and archetypal bikini-clad beauty. But one to which he could never himself belong. Ted was a dreamer. When he died, a little of the dream of the beach as the promised land of freedom drowned in the bath alongside him.

Perhaps those tourists on the Spanish beach – in a recent widely circulated photograph – should not have been quite so shocked at the sight of migrants ditching their dinghy and storming up the beach, for were they not all in search of salvation? At the end of The Order of Things, Michel Foucault says that the very concept of the human is doomed to disappear shortly, “like a face drawn in sand at the edge of the sea”. It seems fitting for the philosopher to go to the beach in search of metaphor and inspiration. For the beach has made philosophers and poets of us all, as we have lived out our fantasies and desires in this twilight zone between earth and ocean, seeing a world in a grain of sand and listening to the sound of the mighty waters rolling ever more. But perhaps our worship of the beach, the product of millions of years of entropy, is itself being eroded and the sands of time are finally running out. I’ll miss it, but the upside is I won’t have to hear the word “awesome” quite so often (I hope).

Andy Martin is the author of ‘Reacher Said Nothing: Lee Child and the Making of Make Me’. He teaches at the University of Cambridge

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments