Competition for a spot in baseball's Hall of Fame reaches fever pitch

Possession of a plaque establishes a player in the pantheon of the game’s greats, but getting into the hall is no easy matter and the decision process is shrouded in controversey, writes James Moore

Halls of fame can be found all over America. Each of the major sports has one. Many individual states have them to honour their local sporting heroes. There’s even one for the media that covers them.

There’s a Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, a Country Music Hall of Fame, a Blues Hall of Fame. There’s one for toys. Believe it or not, there’s one for insurance. There’s probably one for vacuum cleaner salespeople in some sleepy mid western town.

You’d be hard pushed, however, to find one that’s harder to get into, or more passionately debated, than the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York.

It’s a nexus for the rich, and controversial, history of what’s lovingly referred to as “America’s pastime” even though it was long ago eclipsed by American football in terms of its popularity.

With the Boston Red Sox and the New York Yankees bringing the sport’s most storied rivalry to the UK this summer, it’s worth gaining an understanding of this fascinating institution, its arcane procedures, and the heated debates it inspires. They’re particularly intense over three of the game’s former stars who continue to be denied entry.

The achievements of Barry Bonds and Roger Clemens are such that they would have sailed in on their first appearance on the ballot were it not for their alleged histories with the performance-enhancing drugs that disfigured the game during from the late 1980s to the early 2000s.

They have become the poster boys of what has become known as the “steroids era”, though Bonds says he didn't know what he was taking and Clemens has denied being a user.

Curt Schilling is different. He’s just a certified grade A a*****e, and I use that term (with the American spelling) advisedly. Some of Schilling’s public statements almost make Boris Johnson look like a paid up member of the human race. Almost. He’s the Donald Trump of the pitcher’s mound, and then some.

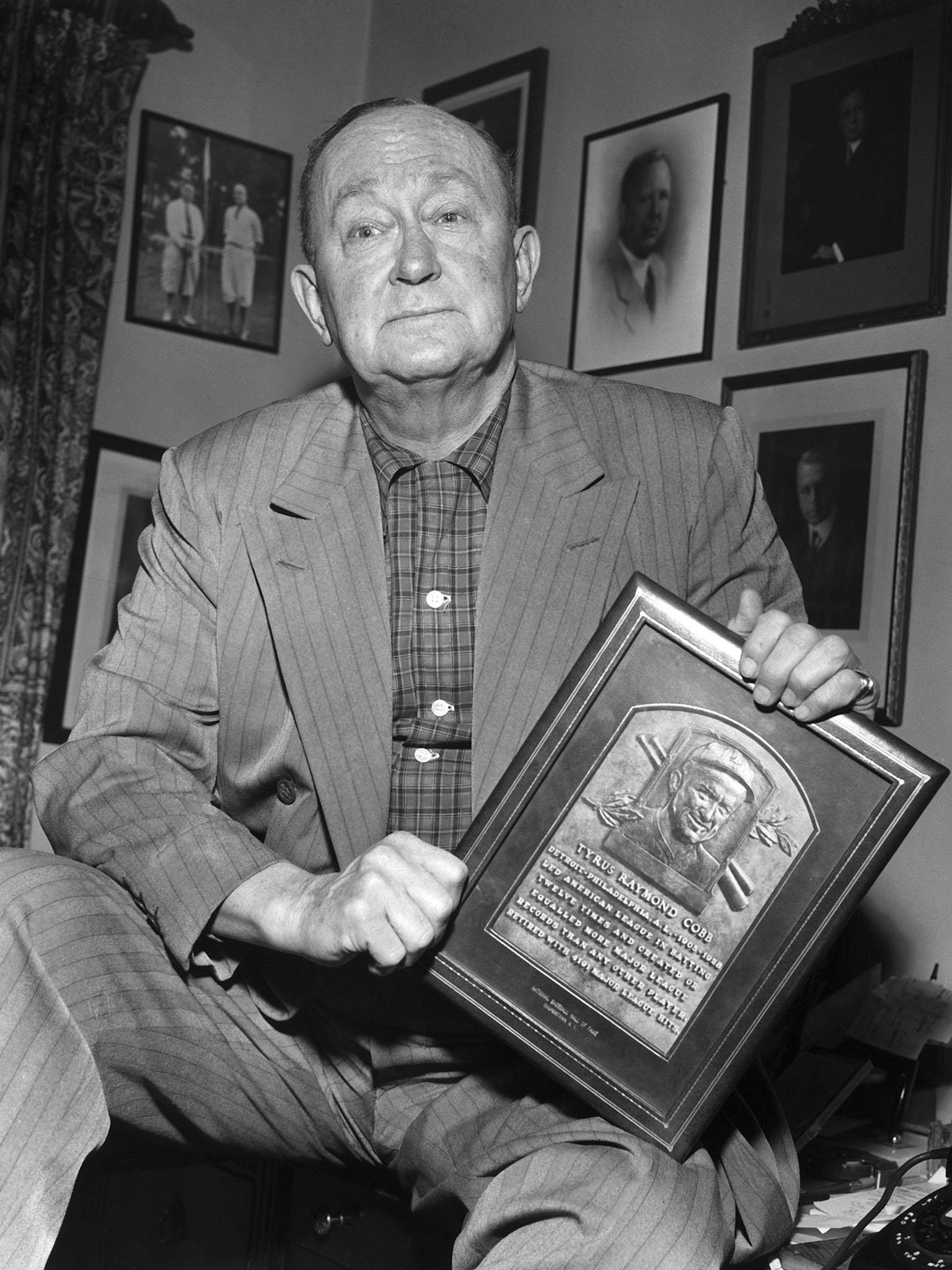

Enshrinement in the hall gets a player nothing more than a bronze plaque in a museum, and the chance to take part in a fancy ceremony in July. But the plaque matters. Possession of one establishes a player in the pantheon of the game’s greats. There are no takeaways, which is important when one considers the subject of steroids. There are surely some users enshrined in the place. But once a player is in, they’re in. They are referred to as “hall of famer” from that point on.

To be eligible for consideration a player needs to have put in at least 10 years of service in the major leagues (there are two; the American and the National league, and their respective champions play in the World Series) and be five years removed from their last season.

The list of those that clear those hurdles is then pared down by a six member screening committee of the Baseball Writers Association of America before it goes out for consideration by its voting members. The latter have to have been active and in good standing for 10 consecutive years.

When you delve into the election process, you start to see why the Baseball Hall of Fame is a good example of why you should never give journalists real power over anything (as if we in Britain needed another one of those given what Johnson and Michael Gove have got up to since somehow securing election to parliament).

Some news organisations – The New York Times is a good example – refuse to allow their writers to submit papers because of what they perceive as the potential conflict of interest in their becoming part of a system they also report on (the stricture doesn’t, however, stop them from writing about whom they would have voted for had they been allowed to).

A player’s name has to feature on 75 per cent of the ballots submitted by voters for them to get in. They can submit up to 10 names, but they don’t have to submit any. That matters more than you might think.

Submitting a blank ballot, as the blogger Murray Chass infamously did a couple of years ago, despite having 34 candidates from which to choose, doesn’t count as an abstention. What Chass effectively did was vote against the entire list. His blank ballot could, in theory, have prevented a player from clearing the 75 per cent threshold to be elected, or pushed one under the 5 per cent a player has to reach to appear on the next year’s ballot. They would then be at the mercy of the Veterans’ Committee, which considers those other than recently retired players. Its decisions, especially this year, have sometimes proved, shall we say, quixotic and would make for an article by themselves.

Most writers give their preferences a little more thought. Some of them positively agonise over their voting papers, and then pen lengthy essays justifying their decisions.

Baseball is a sport of numbers. There are a bewildering array of them that voters can use to judge players’ careers. One of the better ones is Jaws – the Jaffe Wins Above Replacement Score, named for its creator Jay Jaffe, a noted baseball writer and author.

Jaffe developed it to evaluate a player’s career and the strength of their case to enter the hall.

Jaws is what’s known as a “sabremetric” stat, a term coined for the rigorous empirical analysis of the sport that began to emerge in the second half of the last century.

The hit Brad Pitt movie Moneyball focused on the way sabremetrics were used by the small market Oakland A’s under forward thinking general manger Billy Beane, who was grappling with having lost his star players to free spending rivals. To replace their production he looked for cheaper replacements who were undervalued by more traditional measures, with considerable success, although he has yet to deliver a championship.

Jaws is not without its flaws. It doesn’t consider the awards accumulated by a player or take into account individual seasons of stellar greatness.

It doesn’t look at postseason play, either, which certainly matters to fans. Winning the World Series is far more important than player X’s wins above replacement to most of them. Heroics in the postseason become the stuff of which legends are made.

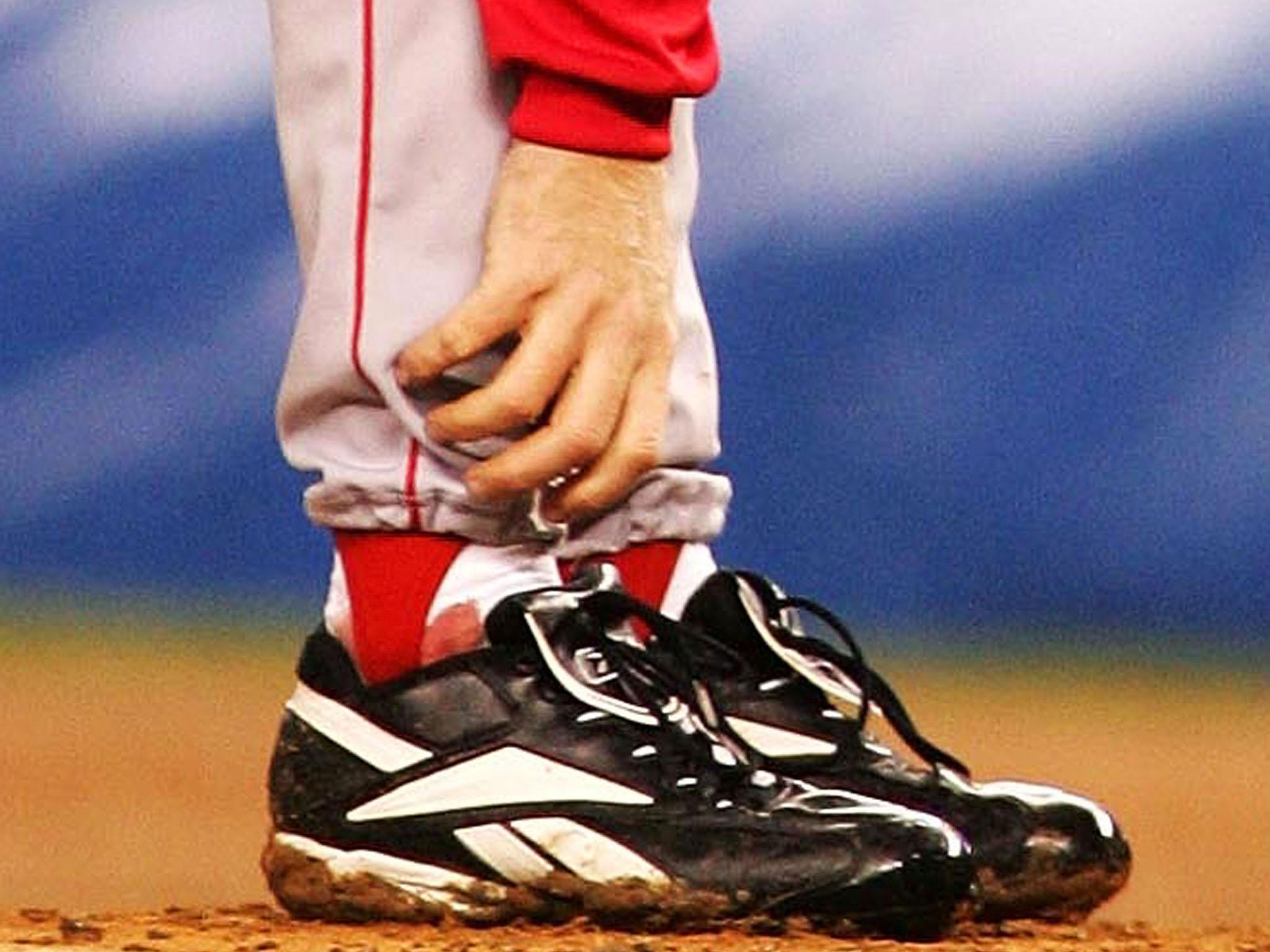

Take Schilling. During the crucial game six of the 2004 American League Championship Series (ALCS) against the New York Yankees, he became a Boston Red Sox hero by stepping up to the mound on an injured and bleeding ankle. The game’s broadcasters famously deployed a camera for the purposes of focusing on the blood that was seeping through his sock. It was at one point loaned to the Hall of Fame by Schilling, where it was displayed until being auctioned off in the wake of his video game company going bust. The purchase price? $92,613 (£72,108).

But enshrinement in the hall is based on a career, not moments of individual heroism like that.

For the purposes of analysing one, Jaws, with its standards for each position, represents a pretty good measure, and to be fair to Jaffe, his exhaustively researched profiles on candidates featured by si.com while he was with the site, went far beyond the numbers.

Bonds and Clemens were streets ahead of their Jaws Hall of Fame standards and for every other standard you’d care to mention (there are quite a few).

Bonds, who played for 22 years for the Pittsburgh Pirates and the San Francisco Giants, was one of the greatest position players to play the game. No one has hit more home runs over a career (762) or in a single season (73).

But he had more than just power. He had speed, and he had precision, and he had the X factor that separates the great from the merely very good.

Such was the fear he inspired among opposing managers that they gave him a free “walk” to first base on more occasions than any other player. There were 2,558 of those during the course of his career.

But of course there were the drugs.

According to the book Game of Shadows, Bonds had taken note of, and was unhappy with, the attention given to Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa during the wild summer of 1998 when the two engaged in a race to beat Roger Maris’s single season home run record. Their protracted duel was even featured on the BBC News at a time when there was no broadband and US sport was a strictly minority interest on these shores.

There were whispers about the possible role played by steroids on the freakish display of hitting the two put on at the time. But baseball, which was struggling to recover from the effects of the 1994-1995 players strike, the longest in its history, turned a blind eye and concentrated on lapping up the attention the sport was getting.

McGwire subsequently admitted to having used steroids. Sosa has been linked to them but has issued repeated denials. The former is off the Hall of Fame ballot, the latter has never looked like gaining much traction.

While they were duking it out, Bonds had been having a stellar season of his own, but his accomplishments were overshadowed. That would soon change. So would Bonds’ slim and athletic build.

A bulked up Bonds broke McGwire’s record in 2001 and went on to become the player all managers feared. He was a seven-time winner of the National League Most Valuable Player award and a 14-time All Star who holds a hat full of records.

But he subsequently became a key figure in the infamous Bay Area Laboratory Cooperative (Balco) scandal and was indicted on perjury charges, having been accused of lying under oath about his alleged steroid use. His eventual conviction was overturned on appeal.

Like Bonds, Clemens was one of the pre-eminent players of the era, set a bewildering array of records, was a perennial All Star (11 times) and a seven-time winner of the Cy Young Award given to the best pitcher in each of the two major leagues.

He also received the American League MVP award in 1986. For a pitcher to win the latter is rare: the existence of the Cy Young makes voters reluctant to consider their candidacies for the other award.

He was in some ways the equivalent to pitching what Bonds was to hitting. A freak of nature. A savant.

He was possessed of both devastating power and guile.

He was also trailed by controversy wherever he went, and like many greats (including Bonds), was possessed of a somewhat “difficult” personality. He demanded, and often received, special treatment from some of the teams he played for. His pre-match routines were sometimes bizarre. He did not come out of the book written by his former manager, Yankees legend Joe Torre, at all well.

Clemens played for 24 years, including stints with the Red Sox, the Toronto Blue Jays and the Houston Astros in addition to the Yankees, which is astonishing considering the wear and tear that pitchers endure. But then, perhaps there’s an explanation for that. Clemens was mentioned 82 times by the report into the steroids era put together by former US senator George Mitchell, though he has denied doping. Others appeared more often, including Bonds. But, as the Associated Press reported at the time, “they didn’t get the worst of it Thursday. That infamy belong to Clemens, the greatest pitcher of his era. The steroids era.”

So Clemens and Bonds wait.

Towards the end of 2017, voters received a mass email from Joe Morgan, a Hall of Fame second baseman who has served on its board since 1994, urging them to reject “players who failed drug tests, admitted using steroids, or were identified as users in MLB’s investigation into steroid abuse”, which resulted in the Mitchell Report. It came at a time when the two were gaining momentum.

The point is often made that when they were being used, steroids weren’t officially banned and there was no testing regimen in place. Morally though? Of course it was cheating. Not everyone played juiced. Some never made it to the majors because others did.

Hall voters have the famous, or rather infamous, character clause to lean on when considering them. To whit: “Voting shall be based upon the player’s record, playing ability, integrity, sportsmanship, character, and contributions to the team(s) on which the player played.”

The problem with using it to exclude Bonds and Clemens? Among the hall’s membership are racists, domestic abusers, spitballers and the admitted users of drugs other than steroids.

Some voters have clearly taken the view that being named in the Mitchell Report is a line they will not cross. But is that line an artificial one? The debate rages on. The smart money is on the pair getting in eventually. It’s just a matter of when.

There has never been the slightest hint of any steroid use on Schilling’s part by any of the books, reports or tests conducted over the years. In fact, he has been a vocal opponent of them, even to the point of arguing for Clemens to be stripped of the Cy Youngs he won after 1987.

His numbers don’t match up to those of his fellow hurler, but almost no one’s do. He never won a Cy Young, much less an MVP, although he did come second in the voting on three occasions.

Schilling often had to share the spotlight with other greats when he pitched, for example, Pedro Martinez in the early part of his career with Boston, and Randy Johnson in Arizona, where he won another World Series. But he was a fearsome pitcher in his own right, particularly in the postseason, with a long list of achievements, and six All Star appearances. Even without his heroics in the run up to the Red Sox’s first World Series win in 86 years in 2004, including that famous ALCS game six, he had an impressive career, the sort that sometimes takes a little time to be recognised with a plaque, but which could be expected to result in one after a few years of consideration.

The problem with Schilling has been his mouth. He’s complained of bias against him because he’s a Republican, stumped for George W Bush in Massachusetts, a notably liberal state, and other GOP candidates, and is a Trump supporter.

But that’s just whinging. There are plenty of conservatives in the hall. There’s more to it than that with Schilling.

He was in the autumn of 2015 suspended from his job as an analyst for ESPN for a tweet about Muslims. Per The Washington Post, he wrote: “The math is staggering when you get to the true #s” and included a meme of Adolf Hitler with the words “It’s said only 5-10 per cent of Muslims are extremists. In 1940, only 7 per cent of Germans were Nazis. How’d that go?”

That was far from the only social media scandal involving Schilling. The network eventually fired him in 2016 for “unacceptable” conduct, which included his posting an offensive Facebook meme concerning transgender bathroom laws.

His comments have only got more inflammatory. He lauded a photo showing a pro-Trump T-shirt advocating lynching that read: “Rope. Tree. Journalist. Some assembly required.” He retweeted a vile conspiracy theory about the Parkland school shooting in Florida. He called Buzzfeed “lying a*s cowards” for their coverage of Alex Jones, the founder of Infowars. Jones has became infamous for pushing crackpot conspiracy theories, including that the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting was a “false flag operation”.

Those are just some of the pitcher’s lowlights and the T-shirt incident led to a dip in Schilling’s voting score.

But it has since recovered. This year’s total will be interesting to watch.

Schilling has come across as a thoroughly nasty piece of work.

But compared with the infamous Ty Cobb, a violent bigot and racist through much of his career, he’s almost like a character from My Little Pony. Needless to say, Cobb is in the hall.

And Schilling will probably make it in the end. Ultimately it’s the Baseball Hall of Fame, and like other bat and ball sports you might care to mention (cricket), skulduggery and people you’d never willingly share a drink with are all part of its rich tapestry.

The results will be announced later this month. Mariano Rivera, the Yankees lights out closer, is the talk of the town at the moment because he may become the first unanimously elected first ballot hall of famer. According to the Hall of Fame tracker of published ballots, the controversial trio are close, but they’ll have to wait at least one more year for the cigars.

The hall’s voters appear to have decided that the best way to deal with the dilemma they’ve created is simply to make them wait.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments