Barbie at 60: Beyond role play what is the point of dolls?

With more than a billion sold, there are probably more Barbies in the US than human beings. That’s an awful lot of plastic to recycle. As Barbie turns 60, Andy Martin wonders if she is past her sell-by date?

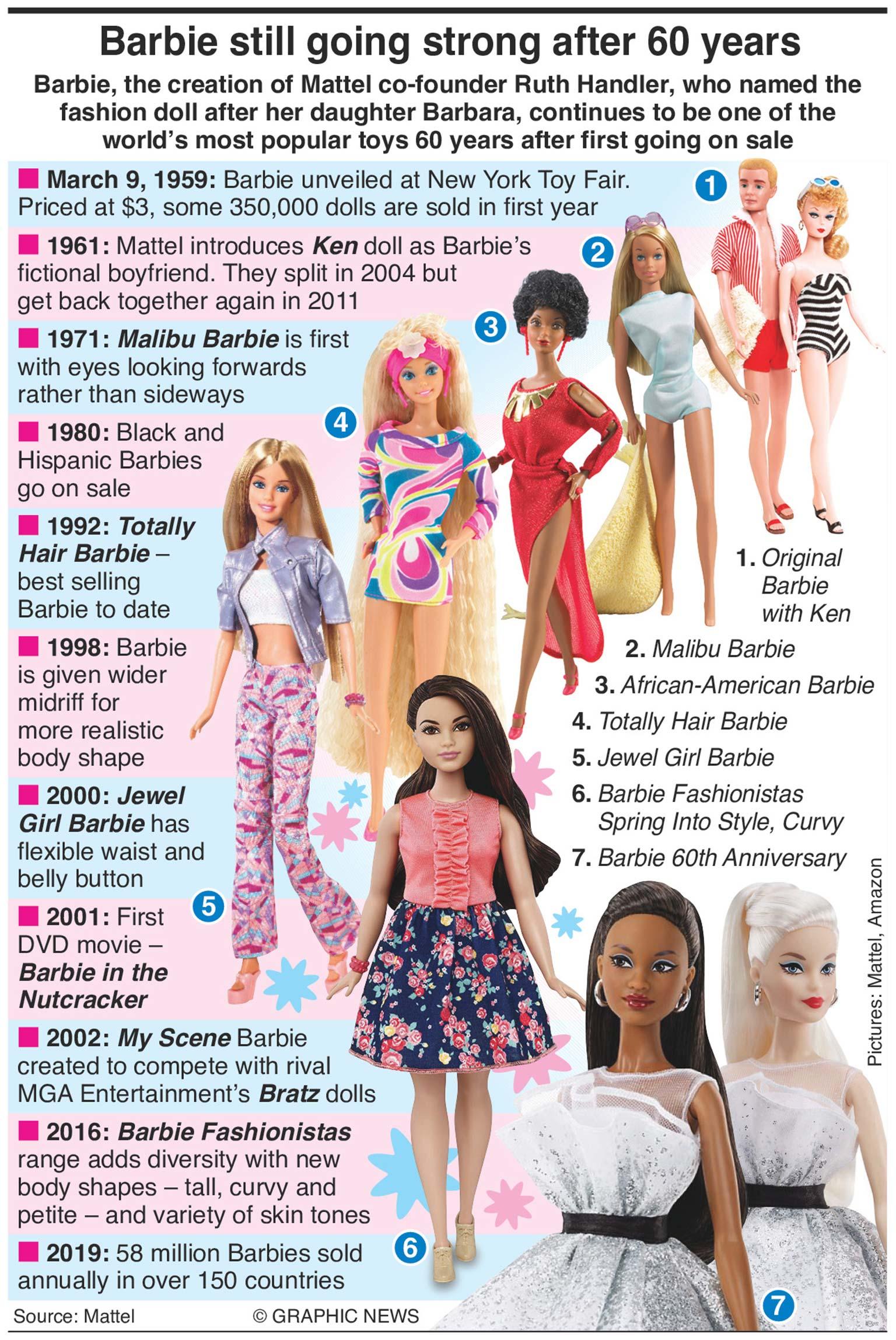

Happy 60th birthday. You don’t look a day over 22.” How often do you get to say that with any degree of conviction? This could be one of those days, because Barbie is turning 60. She came into the world at the American Toy Fair of March 1959, the brainchild of Ruth Handler, president of Mattel, and designer Jack Ryan, based on a semi-pornographic German doll called Lilli and a Playboy fantasy of how girls ought to look.

Handler’s husband (co-founder of Mattel) described her as “anatomically perfect”. Now the makers have gone to meet their maker (Handler died of breast cancer, Ryan blew his brains out), but I know that their creation is still with us, because I dropped in at Hamleys on Regent Street with a notion of buying one. Not something I do every day. In fact, it’s a first, for me, at any rate. Or rather, it would have been.

Only two things deterred me, up on the 2nd floor, populated by dolls of every stripe and colour. There are now too many Barbies to choose from. Did I prefer astronaut Barbie or Mermaid Barbie? Or News anchor Barbie? Talk about embarras de choix. Then there was the small matter of price. I finally zeroed in on a Barbie that bore more than a passing resemblance to model Gigi Hadid (can her hair really be that long?), dressed by Tommy Hilfiger. But that would have set me back a cool £120. Before buying, I opted to consult feedback from satisfied (or dissatisfied) customers. Barbie aficionados.

Kathy (my millennial informant) was, at best, lukewarm. She had had a brief fling with Barbie in her youth. A modest collection. But she inherited them from an older sister and by the time they reached her “they had glue in their hair or had been graffitied.” They played a brief role in her life, between the ages of three to five. But then they faded away when, around the age of six, she became “more interested in dogs and Gameboys”. Her younger sister rejected Barbie entirely in favour of the new Bratz doll (which emerged in 2000 with an even smaller nose and bigger pout but ran into a Mattel lawsuit and was not available in Hamleys).

Finally, I chanced upon a serious Barbie collector, Steph. Not only did she have (and still has somewhere) a Barbie, but she had a Barbie horse too. Her Barbie was known as “Dallas” and her horse had a mane you could groom. “She used to compete in jumping competitions against my Sindys.” Steph had a preference for Sindy (a UK rival) over (American) Barbie.

“Sindy has a more realistic body shape. And is more sporty than glam.” But in fact Steph was more interested in the horses than either Barbie or Sindy. “I had 27 plastic horses at one point.” She gave her dolls riding lessons. When she staged races she would give a horse to her little sister, but the sister complained because she was never allowed to win. “Obviously the dolls were going to be quicker.” She also had another doll called “She-Ra” that rode a pink unicorn.

I finally zeroed in on a Barbie that bore more than a passing resemblance to model Gigi Hadid (can her hair really be that long?), dressed by Tommy Hilfiger. But that would have cost a cool £120

Steph’s only real objection to Barbie was that her anatomy seemed to her (even at the age of seven or eight) “impossible”. She reckoned that to look anything like Barbie you would have to add and subtract – surgically – to a high degree. Which has been attempted. Barbie has been good for cosmetic surgeons. But there is a point at which the positive-thinking Barbie Dreamtopia slogan, “You can be anything”, is indistinguishable from plain old body dysmorphia and self-harming.

My third informant, Rachel, was born not too long after Barbie. But was essentially of the anti-Barbie persuasion. “The parents would not have permitted it,” she said. Did she not yearn for the unattainable Barbie? “No, I also despised,” she said. A little girl in the late sixties, she was precociously aware of diversity.

“I had a collection of dolls representing different countries and cultures.” Barbie was deemed too narrowly unrepresentative, too Aryan, the female homo Americanus. But Rachel was clear as to why she liked playing with dolls: (a) “role play”, acting out, testing out different scenarios, creating narratives with the dolls; (b) “escape from annoying family and friends”. Barbie and anti-Barbie dolls alike are alter egos, portals to alternate, virtual worlds. And as Steph emphasised, they give you, a youngster overshadowed and pushed about by grown-ups, a feeling of control. “I was bossing everyone around.”

Clearly there must be boys who also collect (or collected) Barbies, but I guess they’re in a minority. Maybe some of them, as they grow up, take to life-size inflatable versions. Poised between fashion and porn, Barbie readily lends herself to sex-toy versions. They weren’t available at Hamleys, but I note that I can buy a silicon one – 5’1” tall – from Alibaba, “and she won’t have eyes for anyone but you.” But they’re even more expensive than Gigi Hadid, so I’m going to stick with the ones that are only 11 inches high.

The boys I knew, back in the day, were keener on Action Man. These masculine Barbies were all variations on toy soldiers. And some boys never grew out of them. The most enthusiastic toy soldier collector I ever came across was a surfer named Ted who took his collection with him around the world.

I once found him on a beach in Hawaii, in a lull between waves, re-enacting the battle of the Bulge. Rather like Steph with her horses, he also had a collection of tanks and planes. But the thing that struck me most was that he couldn’t help changing history. It was always, “What if… then the Allies would really be kicking ass.” Barbie, likewise, is a revisionist, imposing herself on history in more ways than one.

Barbie, Sindy, Bratz, and Action Man are all loosely modelled on human beings. So too, Ken, Barbie’s boyfriend, who looks like the most musically inept member of a manufactured boyband. They are simulacra that do and do not resemble the thing they represent. They seem to belong to an alternate universe of perfect, bland features and wasp-like waists. They have smooth, unlined skin. They define “plastic”. Barbie is in part a simplification, a cartoon caricature of a teenage girl, but also a rectification, in accordance with a certain metaphysics.

Let me put my own credentials right out there. I rejected both Action Man and Barbie in favour of dinosaurs. Only the vegetarian ones though. Brontosaurus was a favourite. Rather like the owners of Jurassic Park, I was determined to correct evolution and give the dinosaurs another shot and to hell with any humans who got in the way. I realise now that there is something similarly anti-evolutionary about Barbie and all her kin.

My two kids, both boys, went through a period in their early years in which they collected action hero figures. Batman was probably the most highly treasured. So for a brief while their role models were all superheroes. Including (they fondly, briefly, imagined) me. As I was going out one evening, my then three-year old son, getting ready for bed, asked me where I was going. “I’m going to the Big Fight at Wembley,” I replied. “A World Championship boxing match.” “I hope you win, Dad,” he said sleepily. Obviously mere parents are bound ultimately to disappoint their children. No wonder they turn to Batman.

We have the capability of being disappointed because we can imagine how great everything could be, in an ideal world. And our greatest disappointment is with ourselves. One of the toughest questions my kids used to ask me, once they got beyond the Book of Genesis and started grappling with a non-theocentric sense of time and space, was: “If the theory of evolution is correct, why is that human beings aren’t much better looking?”

If we really were made “in the image of God” then we have to admit that something was lost in translation. The way evolution works, if I can anthropomorphise evolution for a moment (the way Johnny Morris used to do so brilliantly with giraffes and camels), is to say: “There, that’ll do. It’s good enough. What’s your problem? It works, doesn’t it?”

Evolution is not a perfecionist like Goldilocks: things don’t have to be “just right” all the time. I think this may be why a figure like Ken is practically unbearable. He appears to have absolutely nothing wrong with him. It occurs to me, in Hamleys, that someone might seriously want to kill Ken, and pulverise his stupid, smiling face, even if it would be like trying to hold back the tide.

The real problem with Creationism is how did it all go so badly wrong? The supreme advantage of evolutionary theory is that it assumes errors from the very beginning. We are all angst-ridden imperfect copies. Human beings are simply a mistake that took off and multiplied. Barbie is a rational attempt to rectify evolution. This is what female human beings ought to look like. And dress like. It’s as if intelligent design (based on a Barbie-doll theory of creation) was right after all. “There” – to anthropomorphise Barbie’s maker, Ruth Handler, for a moment – “isn’t that better?”

If Venus of Willendorf existed now she would presumably be joining weight watchers or seeking out a personal trainer

Judge Alex Kozinski, who presided over the courtroom battle between Barbie and Bratz, argued that “little girls buy fashion dolls with idealised proportions, which means slightly larger heads, eyes and lips; slightly smaller noses and waists; and slightly longer limbs than those that appear routinely in nature.”

But we didn’t used to be like this, perpetually over-idealising and re-configuring. Look at the Venus of Willendorf, for example. This is an early Barbie, a figurine or statuette, four-and-half inches high, found in Austria, dating from around 30,000BC. But she is also something like the Barbie’s antithesis. As described by Camille Paglia in her book, Sexual Personae, “she is buried in the bulging mass of her own fecund body”. She is definitely female, but possibly not feminine. A primitive earth mother with no face or eyes. If Venus of Willendorf existed now she would presumably be joining weight watchers or seeking out a personal trainer.

Our self-esteem is under attack by our own idealising imaginations. I remember going around the museum at the Parthenon with a Greek friend – a man – who would stand next to all those larger-than-life Greek male gods, all throwing a discus or doing something that would stress their muscularity, with those perfect beards, and he – the Greek guy – felt increasingly depressed by the disparity between the real (him) and the ideal (the statues).

In the era of the Venus of Willendorf, “beauty” had not yet reared its ugly, thermoplastic, engineered, spray-painted head. Beauty is a revolt against nature, dating roughly from the rise of agriculture. Despite Keats, beauty is not truth, it’s one of the greatest fictions we’ve ever come up with. Beauty is an attempt to impose geometry and the rules of architecture on the organic. And it’s a system of control. As Cliff Richard once sang of his “Livin’ Doll”, “I’m gonna lock her up in a trunk so no big hunk can steal her away from me.”

Maybe ugliness is fighting back. Just as we are giving up on plastic straws, so too perhaps it will be possible in the future to ease up on beautiful artefacts too

In many ways the invention of beauty was a disaster for humanity, but there’s no going back. You can’t uninvent it. I think gargoyles, trolls and ugly dolls can help. Maybe ugliness is fighting back. Just as we are giving up on plastic straws, so too perhaps it will be possible in the future to ease up on beautiful artefacts too. Especially the vacuous ones. I know one six-year old in New Jersey who can make princes and princesses out of knives and forks. And a king from a cotton reel.

Maybe like voodoo dolls, you really have to believe in Barbie for her to cast her spell. It’s not that I don’t believe, it’s more that – I realise in Hamleys – I’ve become a full-on misoBarbist. When I look into the cold dead eyes of Ken (and even, to a degree, that Barbie that resembles Gigi Hadid) I can’t help agreeing with Lisa Simpson (in a 1994 episode of The Simpsons): “They cannot keep making dolls like this! Something has to be done!” And, in a similar vein, with Nora, at the end of Ibsen’s Doll’s House, when she storms out of the house and slams the door behind her. Good move.

With over a billion Barbies sold, it seems likely that there are more Barbies in the United States than actual human beings. That’s an awful lot of plastic. I just hope they can be recycled into something useful one day.

Andy Martin is the author of Reacher Said Nothing: Lee Child and the Making of Make Me. He teaches at the University of Cambridge

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments