Babes in the Wood murders: How killer paedophile Russell Bishop was caught by DNA, and tried to accuse victim's father

Trapped by modern forensic science, Bishop tried to get out of it by accusing dead girl’s father Barrie Fellows of murdering his own daughter. Adam Lusher reports

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

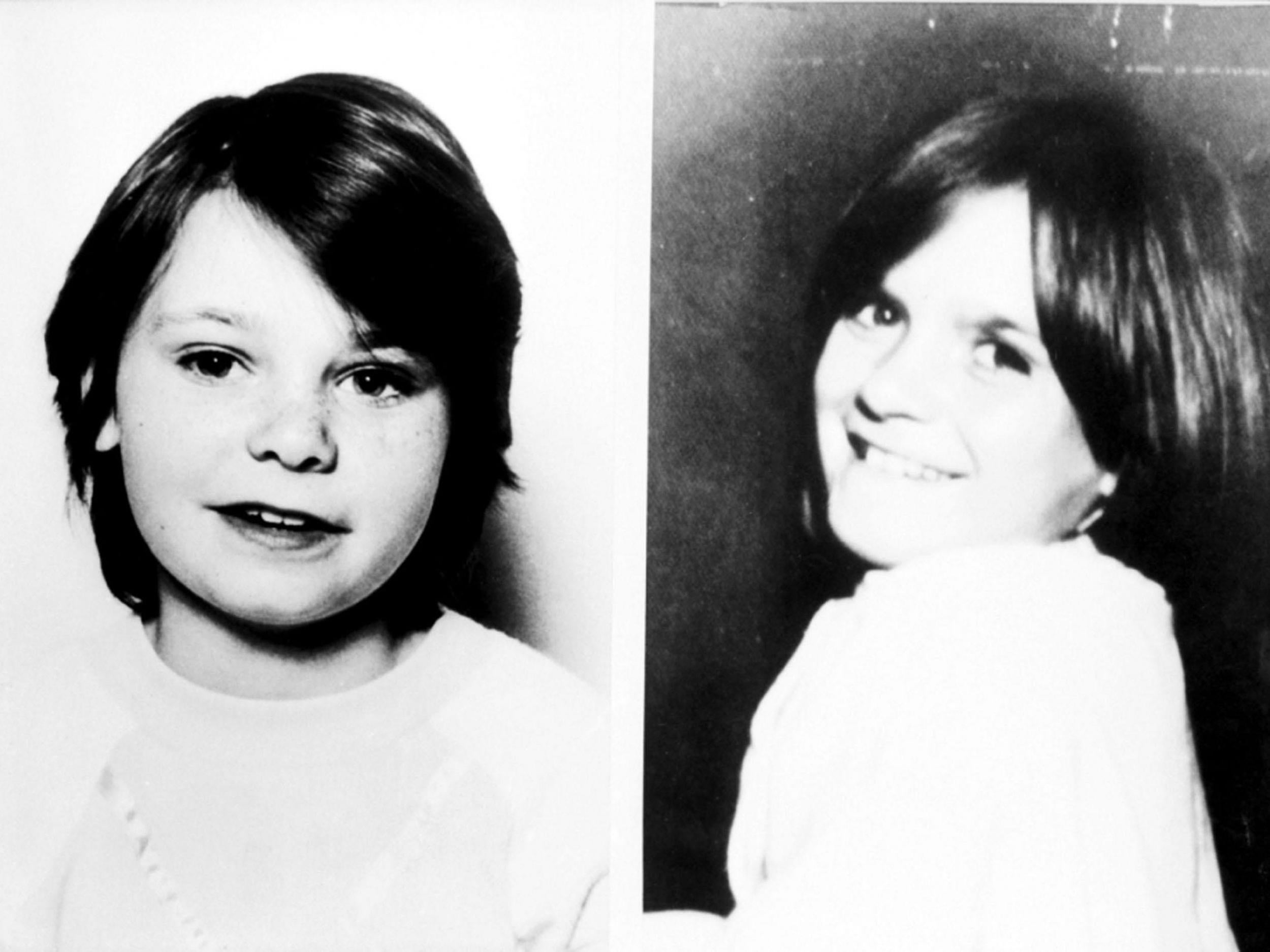

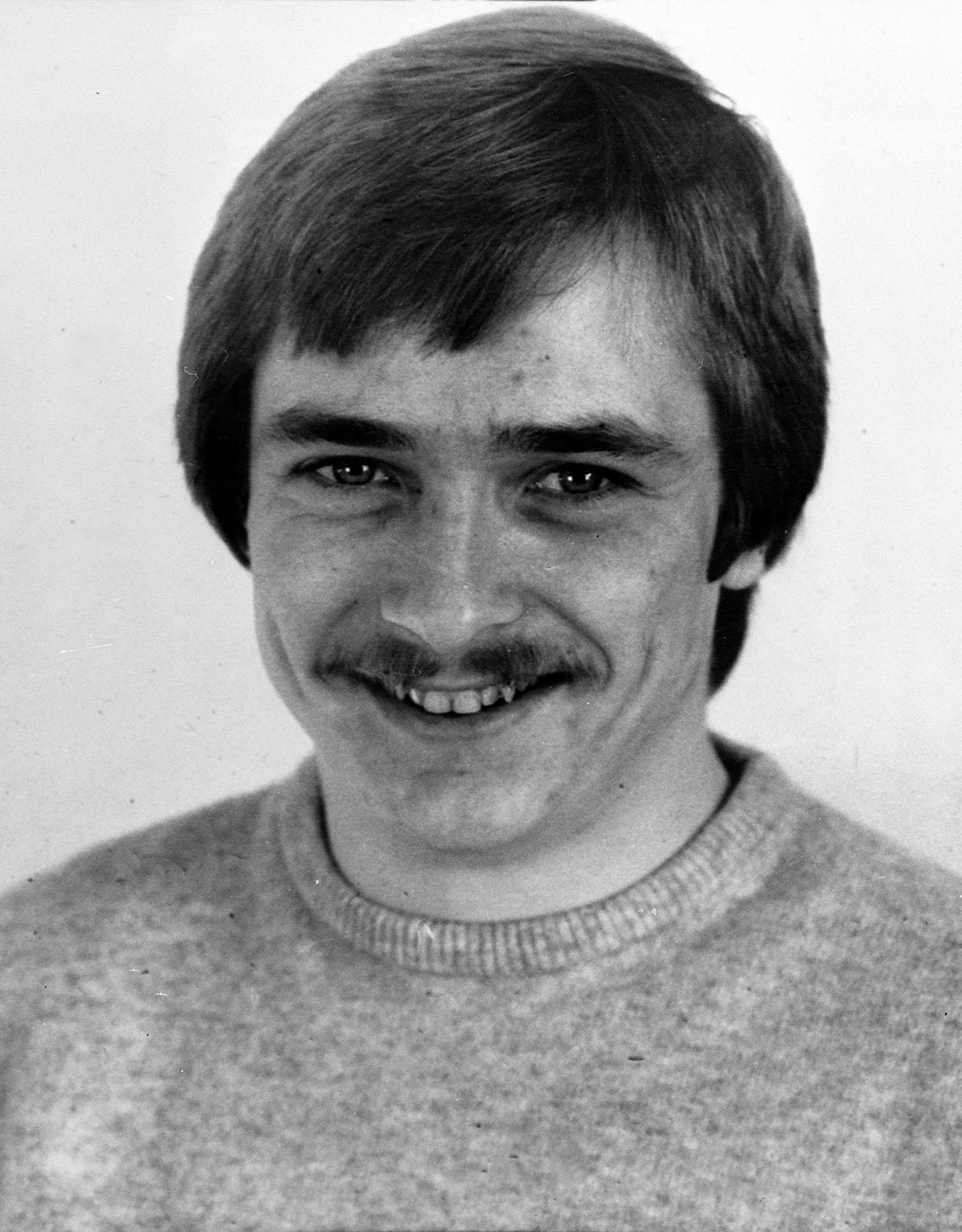

Your support makes all the difference.In December 1987 Russell Bishop walked free after being cleared by a jury of the sexually motivated murders of Brighton’s Babes in the Wood, nine-year-olds Karen Hadaway and Nicola Fellows.

He took to posing as a victim himself, the wronged man falsely accused of a heinous crime he didn’t commit.

But the detectives who had investigated him never wavered in their belief that he was a murdering predatory paedophile.

According to some accounts, it was the same with Karen and Nicola’s families.

Phil Mills, the former long-serving crime reporter for Brighton’s Evening Argus newspaper, tells The Independent: “They may not have said so publicly at that time, but I think they felt that Bishop had to be the killer."

If that is the case, then both the police and the bereaved families had their suspicions about Bishop’s true nature confirmed in the most horrific way imaginable.

A seven-year-old girl violated, strangled and left for dead

At about 4pm on Sunday 4 February 1990, a seven-year-old girl left her home in the Whitehawk area of Brighton to go, on roller blades, to the nearby shops.

As she passed a parked red Ford Cortina, she was grabbed and thrown into the open boot by a man who threatened to kill her if she didn’t keep quiet.

Russell Bishop drove his third victim to the Devil’s Dyke beauty spot in Sussex. He forced the child out of the boot and into the back seat of the car.

He strangled her until she lost consciousness. Then he stripped her naked and sexually assaulted her.

Seemingly convinced the girl was dead, Bishop threw her naked body into some dense gorse bushes hidden in the woods.

The witness he couldn’t silence

This time, though, the girl wasn’t dead. By a near miraculous twist of fate, she had survived.

Phil Mills later heard from investigating police officers what they think had happened.

“Bishop had finished with her,” says Mills. “She was dead. He had killed her. He threw her away like a rag doll. But it seems the shock of the cold evening air and the impact of the gorse thorns did something to kick-start her system again, like a kind of defibrillator.”

Now very much alive, the seven-year-old girl won the universal admiration of detectives by being “an absolutely exceptional witness”.

Before the identity parade, Bishop tried to disguise his appearance by wetting his hair to make it seem darker. The police told him to dry it. The girl picked him out.

In the subsequent trial Bishop, as he would eventually admit in 2018, “didn’t tell the truth in any way shape or form”. He lied throughout. The girl told the truth. The jury believed her.

In December 1990 Bishop received a life sentence for attempted murder, kidnapping and indecent assault.

In that era, when detectives secured a conviction, they usually allowed themselves a moment of private satisfaction – perhaps a drink, maybe a tie made up for all the investigation team to wear, featuring clues and symbols pertinent to the case.

Among the police officers who put Bishop behind bars in 1990, however, there was no tie, no elation.

“We knew two girls had died and never had justice, and then that poor seven-year-old had suffered terribly,” recalls one former detective.

A distressed juror

The point was not lost on others.

As the Argus became the first news outlet to name Bishop as the man arrested in the Devil’s Dyke case, Phil Mills received a telephone call.

“Is it true that Russell Bishop is the man who’s been arrested?” asked the clearly distressed woman at the other end of the telephone. “I was a juror in 1987.”

“I ended up consoling her,” says Mills. “I tried to explain she had nothing to feel bad about because she had done her duty. She had tried the case on the evidence, exactly as the judge had told her to do.”

The families’ campaign for justice for the Babes in the Wood

Some thought the 1990 conviction amounted to justice for Karen and Nicola. “Justice for our Babes,” was one national newspaper headline.

The families, of course, thought very differently. For them, true justice meant Bishop being found guilty and punished for murdering their girls.

And never once did they give up in their campaign to make that happen.

Every year without fail, on the anniversary of the double murder, they put up a banner at the entrance to Brighton’s Wild Park, where Karen and Nicola were killed, demanding: “Justice for the Babes in the Wood”.

They took their campaign to the heart of government, with younger family members laying a wreath in Downing Street in November 2002, as a petition was delivered to the Houses of Parliament demanding changes in the law on sentencing paedophiles and child murderers.

“I have been amazed by their dignity,” says Mills, in comments that would eventually be echoed by Old Bailey trial judge Mr Justice Sweeney. “Every time I spoke to them, there was no serious vitriol. Their only concern was for their dead daughters, whose loss they suffered, and their desire for justice for them.

“And in that they have never given up, not for a single day."

‘Mr Bishop didn’t express any concern for his victim’

Bishop, by contrast, never gave up his pretence of innocence. In 1994, from behind bars, the convicted paedophile began preparing a case against the police and CPS for wrongful imprisonment over the Babes in the Wood case, before abandoning the lawsuit as “too complicated”. In 2001 when paedophile Roy Whiting was convicted of abducting and murdering eight-year-old Sarah Payne in Sussex, Bishop used the case to start suggesting that Whiting was the real Babes in the Wood murderer.

Nor did Bishop ever stop trying to downplay – or ignore – what he had done to the seven-year-old girl. After he first become eligible for parole in 2004, he began agitating to have his attempted murder conviction quashed, seemingly thinking that with “only” kidnapping and indecent assault convictions against him, he might be freed from prison.

Reports written in 2006 drily noted: “Mr Bishop’s main concern appeared to be for his solicitor to get a statement from the victim that he hadn’t strangled her ... Mr Bishop didn’t express any concern for the victim in terms of what memories might resurface, and how it might impact on her by being approached by his solicitor.”

Even at the Old Bailey in 2018 Bishop seemed in a twisted yet pathetic state of denial about the grossest aspects of the 1990 sex attack. He could admit to indecently assaulting a seven-year-old girl to “belittle and shame her” – seemingly oblivious to how shocking that was to everyone else in court – but he couldn’t bring himself to confess to a sexual interest in children.

Even when the evidence for it was overwhelming.

Prison letters to a 13-year-old girl

Prosecutor Brian Altman QC confronted him with the letters he had written to a 13-year-old from prison in 1987, while on remand awaiting the first Babes in the Wood murder trial.

There was line after line of it: “Don’t give this letter to no one, not to your mum, not to anyone ... You will have to go on the pill … How old are you baby, hee hee. It don’t matter … I still say you won’t handle 12 inches....”

Mr Altman asked: “Twelve inches of what, Mr Bishop?”

Lamely, the defendant replied: “It speaks for itself, doesn’t it?”

He still kept insisting he had thought the girl was about to turn 16 in 1987, even after Mr Altman read him his letter in which he spoke of the girl having been 11 when he met her in 1984.

“This is all rubbish,” Mr Altman told him. “This is all lies. You have a sexual interest in children. You are a paedophile.”

Rather than face the truth, Bishop fled from his accuser, abandoning the witness stand halfway through Mr Altman’s cross-examination by telling the judge: “My lord, if I may, I have finished giving evidence.”

But the barriers between the paedophile and a double murder conviction had already crumbled.

DNA and the past catch up with Russell Bishop

The process began in 2005 when Tony Blair’s government abolished the double jeopardy rule which had prevented suspects acquitted by a jury from facing a second trial for the same crime.

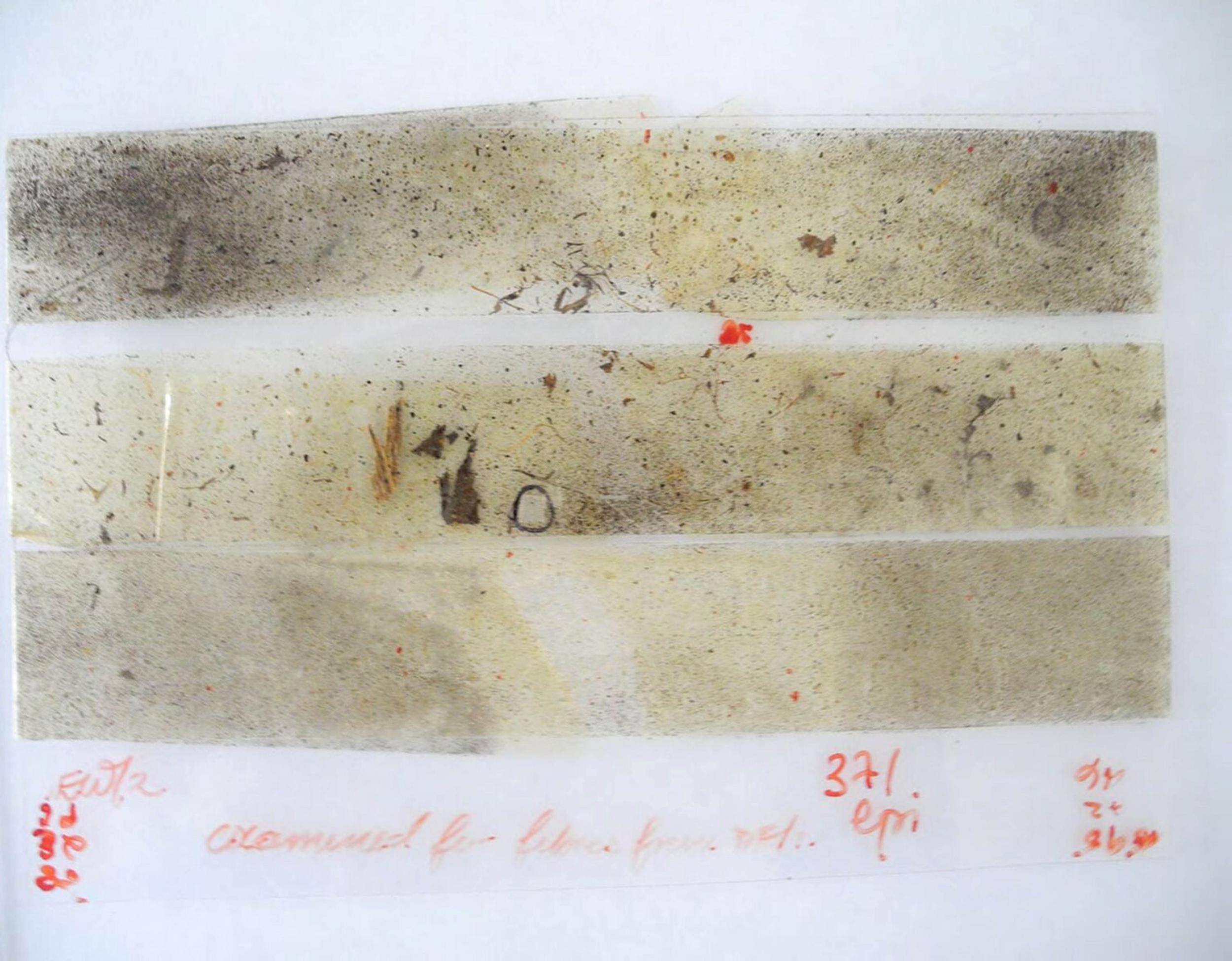

In 2006 Sussex Police decided to hold their fire, aware that they would be allowed only one attempt at a double jeopardy prosecution. But the forensic samples taken in 1986 were still there, still waiting for the science to catch up with Bishop.

And in 2011, Sussex Police started yet another cold-case review.

By 2014 they were ready for Roy Green, a senior scientific adviser at the independent Eurofins Forensic Services laboratory, to examine samples taken from Karen’s left forearm during her 1986 postmortem.

In 1986, with DNA profiling in its infancy, the hope had instead been to find tell-tale hair or fibre evidence.

But in 2014 Mr Green was able to look for skin flakes that would yield DNA which could then be analysed using some of the most advanced techniques known to 21st century science.

DNA-17 short tandem repeat (DNA-17 STR) testing detected an incomplete profile matching that of Bishop. Y23 Y-STR profiling, a sensitive technique specific to male DNA, found components matching Bishop.

Mr Green also noted Karen’s DNA and the genetic material of a third person.

He would go on to tell the Old Bailey that it was a billion times more likely that he had found DNA from Bishop, Karen and an unknown person than if he had just detected genetic material from the girl and two unidentified people.

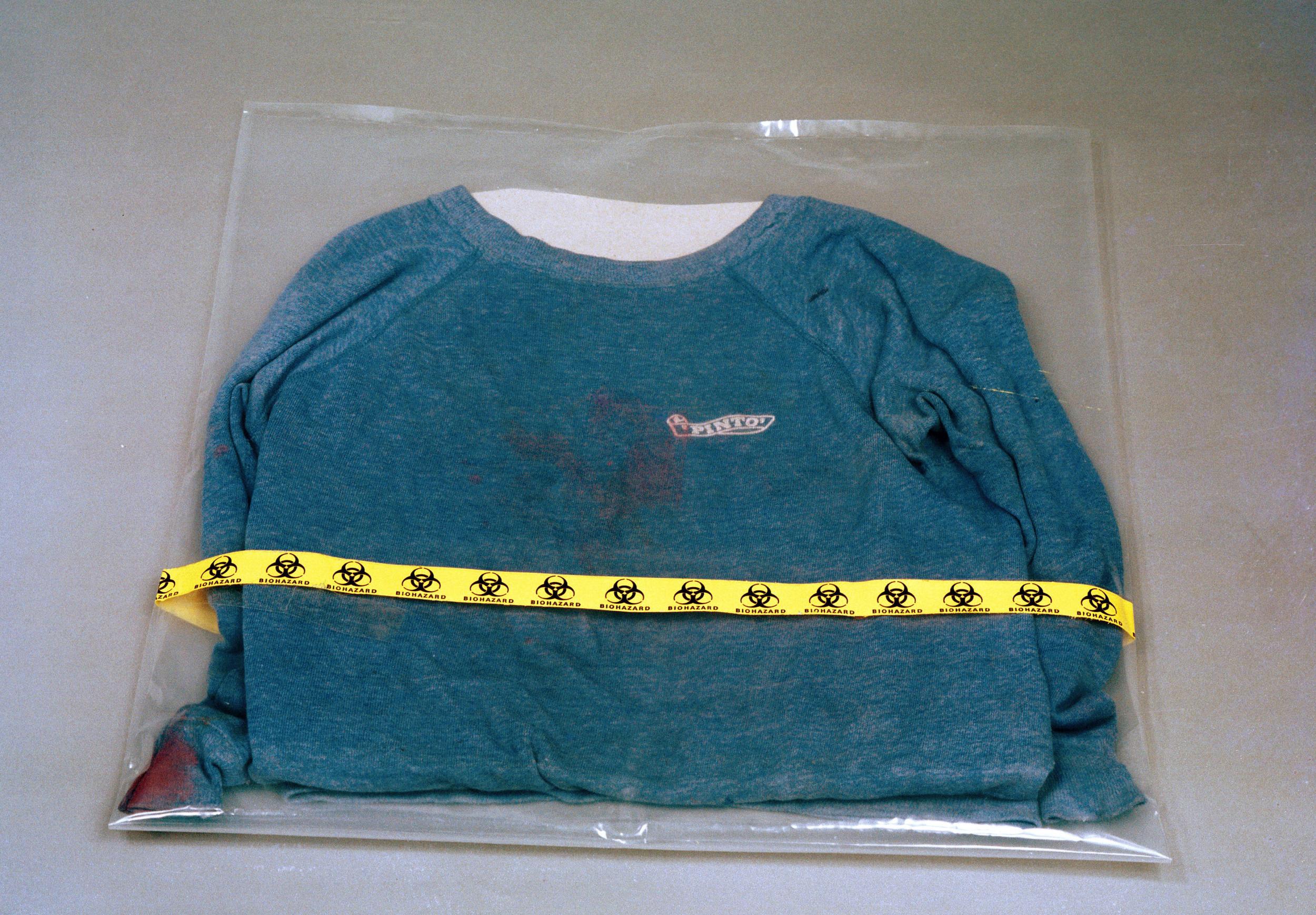

When he looked at samples from the Pinto sweatshirt that the police had always said Bishop wore during the murders, Mr Green found DNA traces that were more than a billion times more likely to have come from the original defendant and an unknown than from two mystery people.

Here was the substantial new evidence the families and the police had been waiting for.

On 10 May 2016 category A prisoner and convicted sex offender Russell Bishop was shocked to see that the van he thought was transferring him from HMP Frankland to a new jail had instead rolled into Durham police station. Officers from Sussex were waiting to rearrest him on suspicion of the murders of Karen Hadaway and Nicola Fellows.

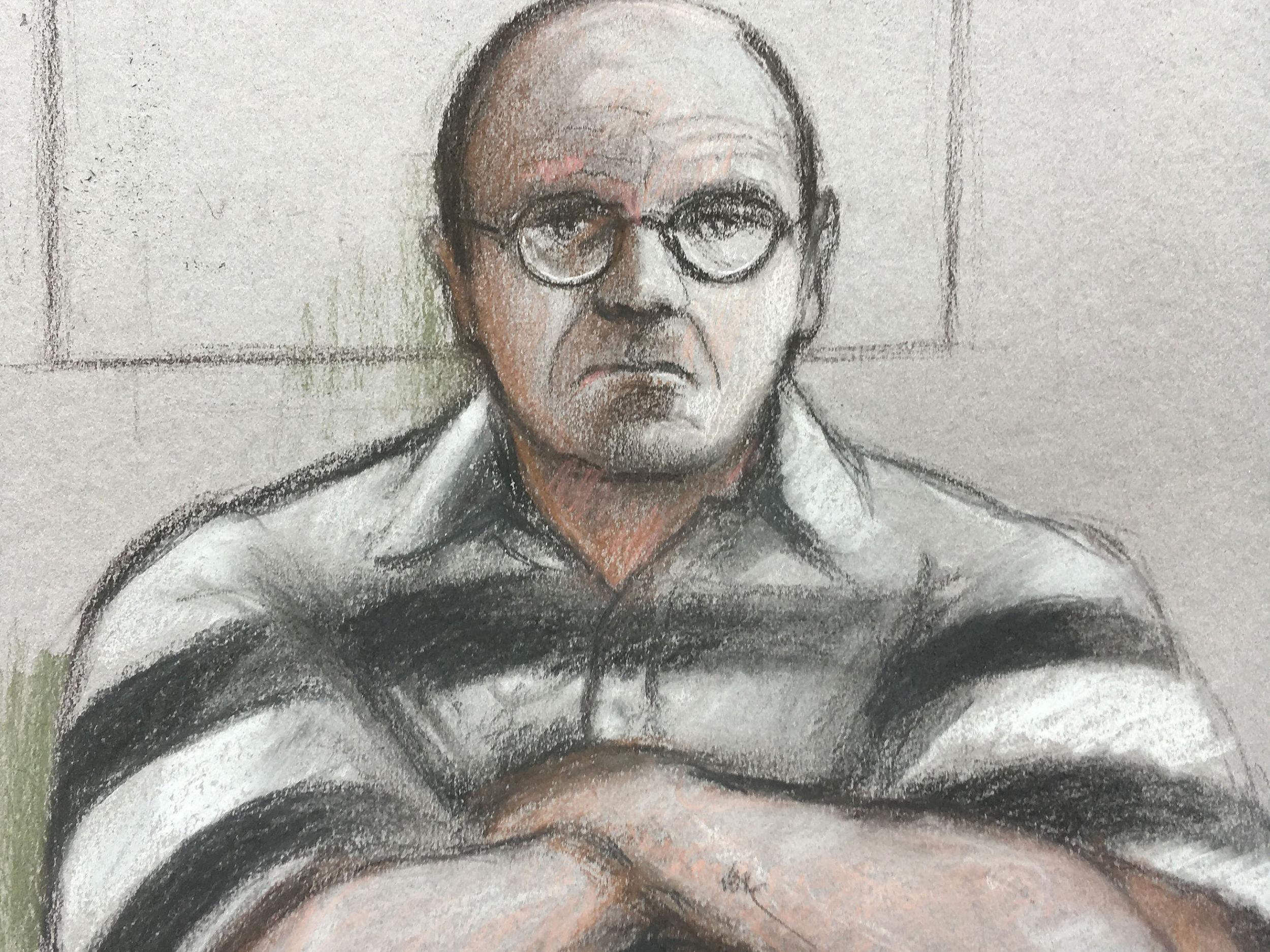

As Bishop glared from the dock at the Old Bailey the forensic samples taken in 1986, and dismissed by the 1987 defence team as examples of bungling cross-contamination, were now presented in the way police and prosecutors had seen them: as skilfully assembled evidence.

“Locked in time and place,” for three decades, said prosecutor Brian Altman QC. “A time capsule” that provided “devastating evidence” of Bishop's guilt.

Bishop tried to explain it away by claiming the DNA proved what he had been saying all along: that when the bodies were first discovered, he had gone into the ‘den’ and checked them for a pulse.

Unfortunately for the paedophile, however, he hadn’t been saying that all along. He had been chopping and changing constantly, even during the course of a single police interview.

“As a liar,” Mr Altman observed, “He is just not a very good one. He forgets the lies he has told.”

Bishop, the jury heard, was “tailoring his evidence” to fit the inconvenient fact of his DNA on a dead girl’s body.

Kevin Rowland, one of the two men who found the bodies, shot down the latest lie by saying he had stopped Bishop from going into the den to see the bodies, or check their pulses.

On Bishop's behalf, Joel Bennathan QC, defending, tried to dismiss the prosecution's forensic time capsule as “leaky” and hopelessly compromised by cross-contamination when collected and examined in 1986.

Bishop himself tried to claim that in 1986 a scenes of crime officer had examined the Pinto sweatshirt “on the same table in the same room”.

But the prosecution was able to show that although knowledge of DNA may have been in its infancy in 1986, awareness of the dangers of cross-contamination of evidence wasn’t.

Independent expert Rosalyn Hammond testified that she had gone through everything that happened to every exhibit from 1986 onwards, and had concluded there was no realistic possibility that the forensic evidence presented in court had come from cross-contamination.

‘The cruel and desperate defence of a desperate man’

Faced with forensic evidence more powerful than anything that had been possible in 1987, Bishop instructed his 2018 defence team to adopt a new tactic.

In 1987 Bishop’s barrister Ivan Lawrence QC had expressed regret that Nicola’s father Barrie Fellows had stormed out of Lewes Crown Court before he could make it clear that the defence was not “for a moment” suggesting that the bereaved parent was the murderer.

There was no such delicacy in 2018.

All the old local gossip about Mr Fellows having been the real prime suspect was allowed to resurface.

Despite bitter prosecution protests that these were “nothing more than unsubstantiated salacious allegations”, judge Mr Justice Sweeney allowed the jury to hear claims that Mr Fellows was seen watching a pornographic video of Nicola in bed with a lodger two to three months before her death.

Outside court Detective Superintendent Jeff Riley, the man who led the cold-case investigation, called it “a particularly cruel way to run a defence: desperate measures by a desperate man”.

On Bishop’s instructions, Mr Bennathan suggested to the jurors that Mr Fellows “had a guilty secret: he had been complicit in the abuse of Nicola”.

It was possible, the lawyer argued, that the “the police and prosecution have spent 32 years building a case against the wrong man”.

The court heard claims that when Barrie Fellows lost his temper, Nicola would “stand and shake” with fear, that he had once threatened to chop her fingers off for pilfering items from school, that he had deliberately broken his grandmother-in-law’s nose during a row.

“If we are looking for a man capable of really exceptional violence,” Mr Bennathan told the jury. “It does build up a picture.”

Rather forlornly, Mr Fellows, 69, denied being so violent, insisting he had never intended to hurt his grandmother-in-law, that it had been an accident.

“Seriously, sir,” he told Mr Bennathan. “I do not deliberately punch old ladies on the nose.”

He answered “no” when Mr Bennathan asked him: “Were you party to Nicola being filmed for a pornographic video?”

He gave the same response when asked: “Were you and another man in your front room watching a homemade video of your own daughter?”

He was close to tears by the time he had to answer no to the question: “Were you anything to do with her death?”

And after Mr Bennathan finished his defence summing up, Mr Fellows was seen outside court, wiping away tears, being comforted by police, and – perhaps tellingly – by the Hadaway family too.

He had just heard Bishop’s defence barrister tell the jury the fact that the killer put Nicola’s knickers back on might point to “a weird, almost inconceivable mix of lust and violence on the one hand”, and parental love on the other.

“Nicola was the target of the worst abuse,” said Mr Bennathan, as Mr Fellows looked on. “Nicola was the target of the greater violence. And yet someone cares enough to redress her afterwards.

“We know some fathers do kill their children."

In all of this, the man accused of being in the video, former lodger Dougie Judd, became almost collateral damage.

In court he dismissed the allegations about such a video existing as lies so preposterous that when he first heard them he thought they were “a wind-up”.

Outside court, one source told The Independent: “That allegation has hung over him all his life, stopped him getting jobs.”

Back in court number 16, pathologist Dr Nathaniel Cary corroborated the emphatic denials of Mr Fellows and Mr Judd.

He had looked at the records of Nicola’s postmortem, Dr Cary said, and there was no evidence she had been subjected to sexual abuse in the months leading up to her death.

Perhaps there was also another victim of collateral damage: Bishop’s former teenage lover Marion Stevenson, the woman who actually made the video allegations, most notably in a News of the World article published three days after the 1987 acquittal. She told the Old Bailey she was put up to going to the now defunct tabloid by Bishop’s “domineering” mother Sylvia.

“She wouldn’t have anything to do with me before I said I thought Russell Bishop was innocent,” Ms Stevenson told the court, before bursting into tears and sobbing: “They all used me. Everyone used me: Russell’s family, the police, everyone.”

“She was exploited by the defendant through his mother,” Mr Altman suggested to the jury. “And she is still being exploited by the defendant after all these years.”

Under his cross-examination, Ms Stevenson broke down in tears again, accusing Mr Altman of “trying to make me out to be a liar”.

She did, however, concede that on the day she claimed to have seen Mr Fellows watching the video, she had been drinking, and “smoking joint after joint” of cannabis.

"It did affect my memory when I was smoking pot," she admitted.

The ‘first love’ who was a violent, self-obsessed pathological liar

Rather curiously, there were also times when Ms Stevenson sounded more like a prosecution witness than one called by the defence.

Now 48, with her affection for Bishop long ago replaced by disgust, she more than any other witness was able to show how her “first love” was a violent, self-obsessed pathological liar.

It was via the statements she gave to police in 1986 that the Old Bailey heard how Bishop had dismissed what had happened to Karen and Nicola by saying: “They deserved it, and I blame the parents for allowing them out at night.”

Having closed that discussion about the children he had killed just two days earlier, the court heard, Bishop demanded sex from his 16-year-old lover and became cross when she refused because she was so upset about the murders.

All the evidence, it now seemed, was pointing to Bishop. There were no extraordinary scenes involving prosecution witnesses, no forensic science experts pinned against a wall by an angry detective after giving evidence, as there had been in 1987.

This time it was Bishop providing the courtroom incident, with his plea to be released from the cross-examination of Mr Altman.

The jury was not allowed to see him being taken to and from the witness box in clanking manacles.

But they saw and heard plenty enough to convict him.

Justice delayed is justice denied?

After 32 years, two families finally have a conviction. But it seems there can be no grimmer example than the Babes in the Wood case of the maxim that “justice delayed is justice denied”.

In the courtroom mayhem that followed Bishop’s 1987 acquittal on the count of murdering Karen Hadaway, not everyone noticed how the girl’s father Lee had buried his head in his hands and wept.

Eleven years later, in 1998, Mr Hadaway died of a heart attack aged 50. His friends and family described him as a father who died of a broken heart. In no way does Phil Mills consider that a fanciful suggestion.

“We all know what stress can do to the body,” he says.

By the time she got to attend every day of the Old Bailey trial, Michelle Hadaway too appeared in failing health, offering brave smiles to her daughters or friends in the public gallery, but with a lined, careworn face. The 61-year-old often needed a wheelchair to get into and out of the courtroom.

For Barrie Fellows, meanwhile, what he suffered at the trial was the culmination of three decades of ill-founded gossip that he murdered his own child.

After describing through tears what it was like to have to have to identify “my little girl” as she lay on a mortuary slab, Mr Fellows told the Old Bailey he had been waiting since the 1980s for the police “to say publicly I was not guilty of my daughter’s murder”.

Even then, as the court heard the by now overwhelmingly damning evidence against Bishop, The Independent could still find people in Brighton who remained utterly convinced – yet utterly deluded – that Mr Fellows was the real Babes in the Wood killer.

“Russell would never have worn that Pinto sweatshirt,” was the rather spurious argument of one Moulsecoomb woman. “He loved to wear his sweatshirts tight. Russell had a beautiful body.”

Such has been the wounding power of the false allegations that in 2009 Sussex Police felt obliged to travel to Mr Fellows’ new home in the north of England and arrest him, not for the murder itself, but on the suspicion of colluding in the sexual abuse of Nicola.

After 12 weeks of thorough investigation, the police found not a scrap of evidence to back up the unfounded claims about the video and the abuse. They took no further action against Mr Fellows.

At the time, Mr Fellows told The Independent that the 12 weeks it had taken the police to clear him then had been “hell”. The supermarket where he worked told him to stay away for fear of vigilante attacks.

He knew it was all lies, Mr Fellows said, but there was no getting away from the fact that his daughter’s death had returned to haunt him.

“I have done nothing wrong,” the bereaved father told The Independent. “All I have done is lose my daughter in the most horrific of circumstances.”

“The deaths of my daughter and her friend,” said Mr Fellows in 2009, “Destroyed two families.”

And then Russell Bishop decided he would try to worm out of his guilt by pinning the blame on the father of the nine-year-old girl he had murdered.

Faced with such suffering, it would be glib indeed to talk of perfect justice, or of that word so rarely heard in 1986: “closure”.

Instead, says Mills: “I hope the verdict gives the families a sense of peace.

"I don’t think it’s possible for it to give them closure.”