How a 1961 photo essay uncovered the crisis in Latin America... and saved a 12-year-old boy

Photos of an asthmatic boy prompted an outpouring of American generosity and a Brazilian backlash. Sebastian Smee looks back at the work of Gordon Parks

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Five months after the inauguration of president John Kennedy, Gordon Parks, the famous photographer for Life magazine, found himself on a plane to Rio de Janeiro. As he cruised along at 30,000 feet, an immense thought pressed in: I am about to save a boy’s life.

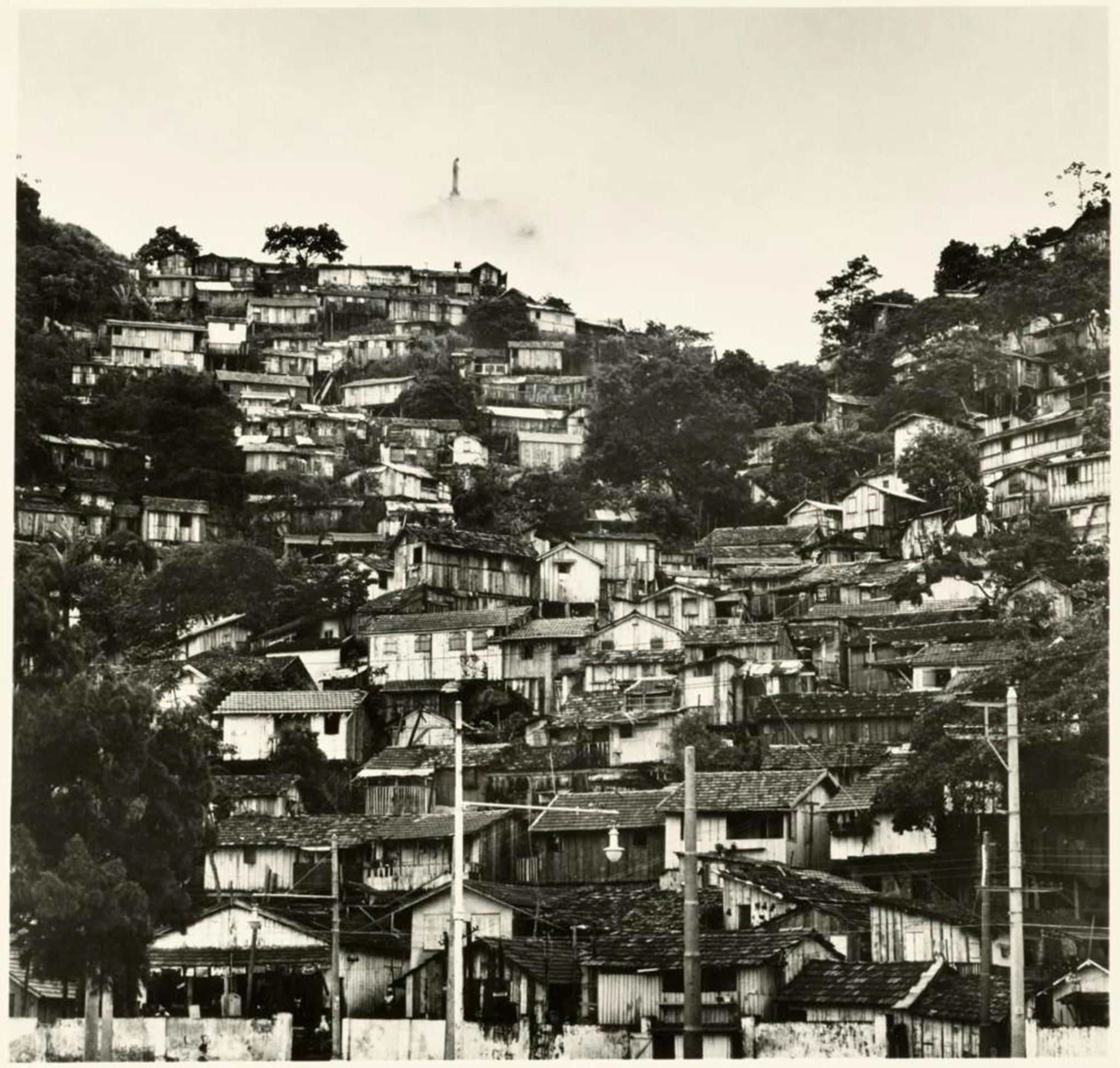

His name was Flavio da Silva, and he lived in a favela called Catacumba on the steep hillsides of Rio. Days earlier, the boy had written: “This is a dream, and I shall end by awakening.”

But it wasn’t. It wasn’t a dream. It was his life.

His life.

Though neither he nor Parks could have foreseen it, Flavio was about to become a pawn in a battle between two media titans: one in the United States, the other in Brazil. Both publications were trying to influence public opinion at a time when the ideological and geopolitical stakes felt frighteningly high.

Parks originally journeyed to Brazil for a Life assignment on 20 March 1961, just as Kennedy was proposing a foreign aid programme aimed at improving cooperation between Latin America and the US. Life’s circulation at the time was around 7 million copies, the highest in the land, and its Republican-leaning editors weren’t shy about using that influence.

It was the height of the Cold War. Fidel Castro’s grip on Cuba had tightened after the Bay of Pigs fiasco. Latin America looked vulnerable to a communist takeover. Life decided to launch a five-part series titled “Crisis in Latin America”. Parks, the first African American to work as a staff photographer at the magazine, was assigned to the second part.

Brazil, like the US, had a new president, Jânio Quadros. Quadros inherited an economy in crisis. He implemented an austerity programme, of which the US approved. But when the United States offered $300m (£234m) in foreign aid in return for cooperating with US opposition to Castro’s Cuba, Quadros rejected it. The offer, he felt, was an insult to Brazil’s autonomy. It was tantamount to a bribe.

Life editors liked to script photo assignments in advance. Parks was told to go to the Rio favelas, “find an impoverished father with a family of eight to 10 children. Show how he earns a living. Explore his political leanings. Is he a communist, or about to become one?”

They wanted Parks to round out the family shots with images providing some social context: ideally, a political rally in the favelas.

Parks had been uneasy about the assignment from the beginning. He had his own ideas. But an ally at Life urged him to accept, saying: “Rio de Janeiro is a long, long way from Rockefeller Plaza. Who knows, you might just misinterpret your instructions?”

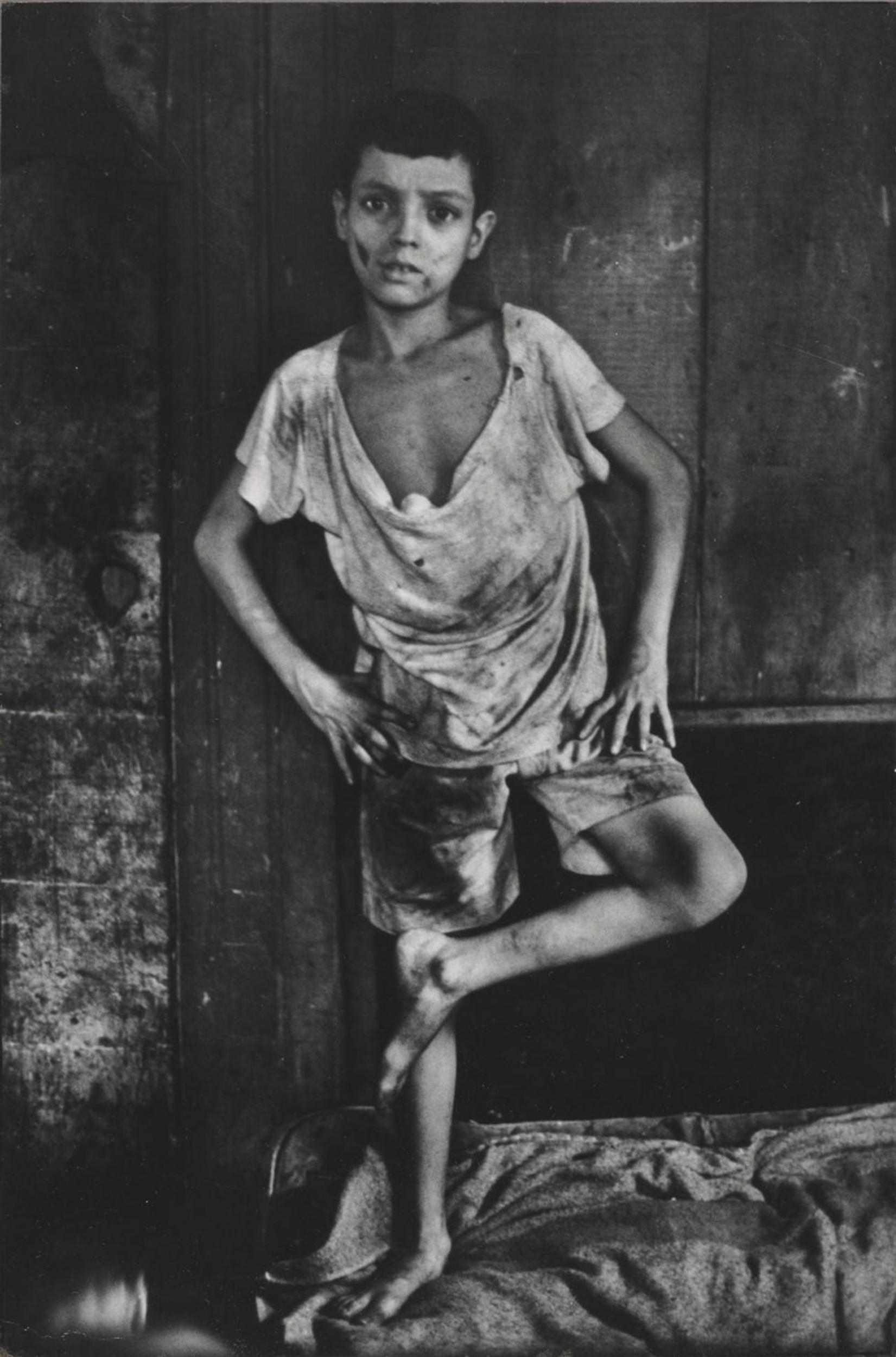

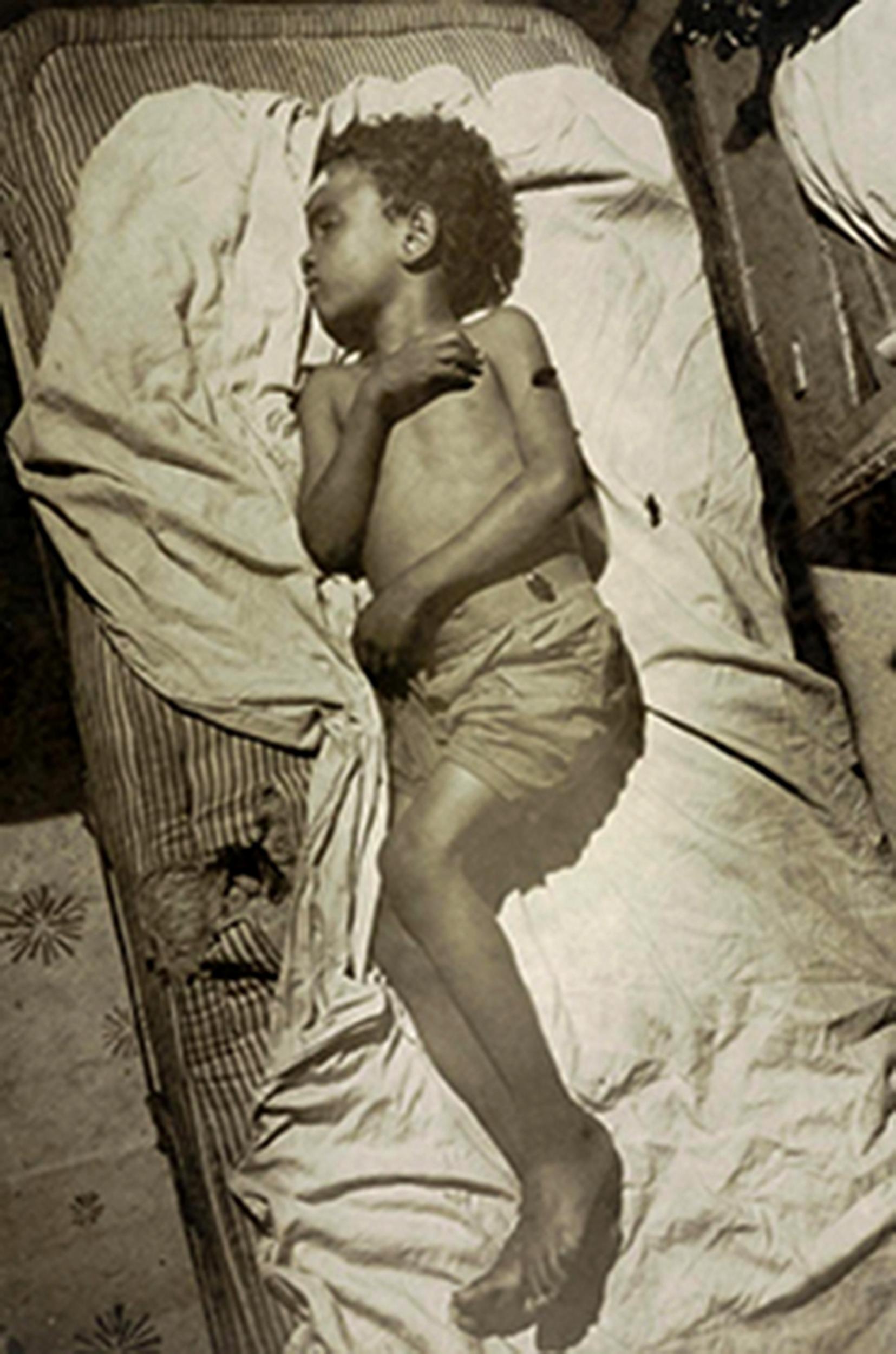

The first thing was to find a suitable family. Parks went to the favelas on a steaming hot day in March 1961. He was accompanied by José Gallo, who managed the local bureau of Time Inc, Life’s owner. As they climbed up a “tangled maze of shacks”, Parks saw Flavio, who was carrying a 40-pound tin of water on his head and who – he would soon discover – suffered from severe asthma.

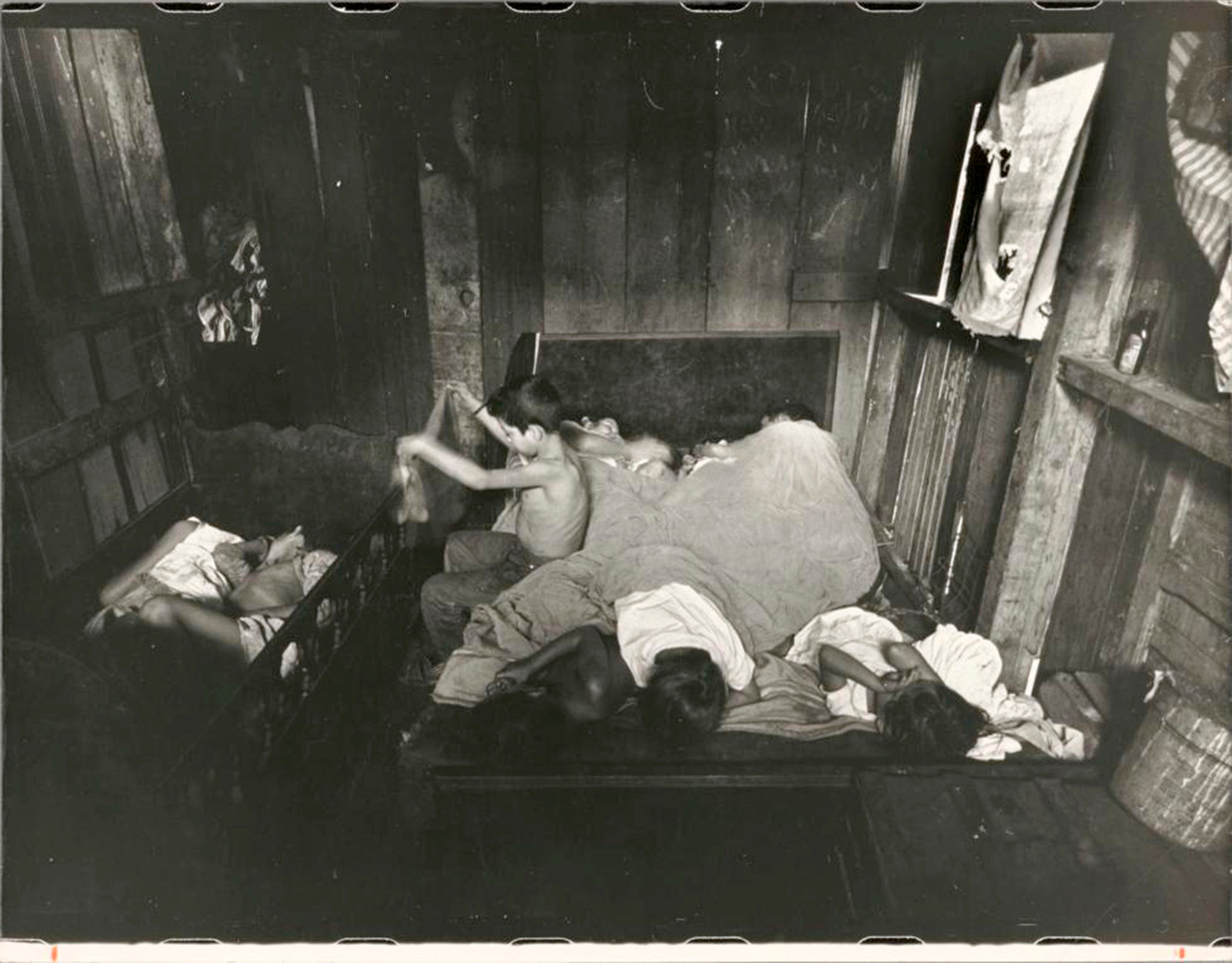

“He was horribly thin,” Parks wrote, “naked but for his ragged pants. His legs looked like sticks covered with skin and screwed into two dirty feet. He stopped for breath, coughing, his chest heaving as the water slopped over his shoulder and distended belly.”

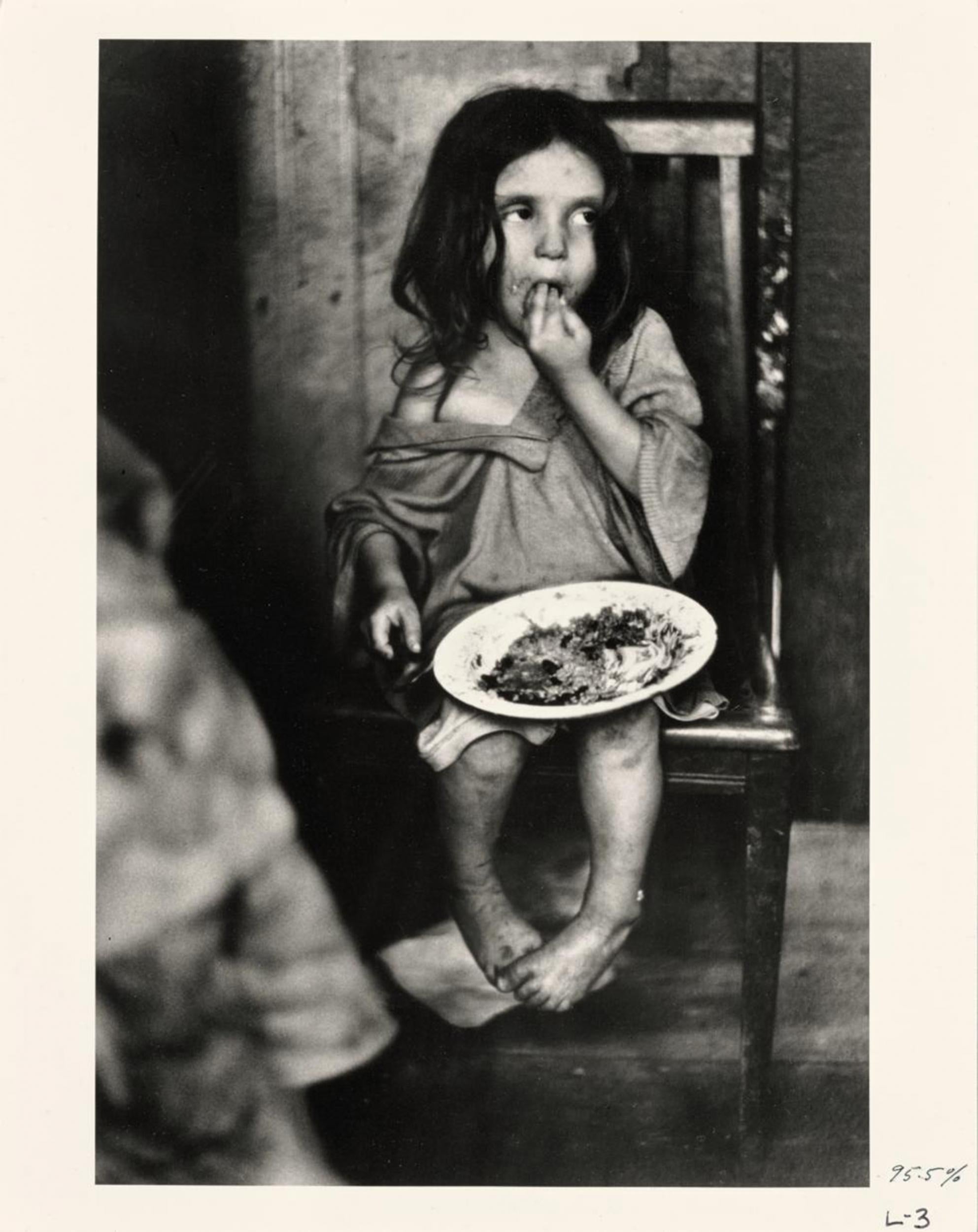

Parks had his subject. He met Flavio’s seven siblings in their home, high up the Catacumba hillside, and, that evening, his parents. Flavio’s mother, Nair, worked as a washerwoman. She was 35, and pregnant with their ninth child. His father, José Manuel, was 42. He had a kiosk selling kerosene and detergent.

Parks had travelled widely – including an earlier trip to Rio – but never had he seen such destitution. He and Gallo explained themselves and asked for permission to carry out their assignment. “You can photograph us,” José replied, eventually, “but you must show us in a good light.”

“Just doing my job,” we journalists tell ourselves. The lives we affect, and sometimes rearrange, are rarely changed intentionally. We maintain this stance even when it feels suspiciously convenient, discharging us from the obligation to anticipate consequences.

Then again, some consequences are hard to anticipate.

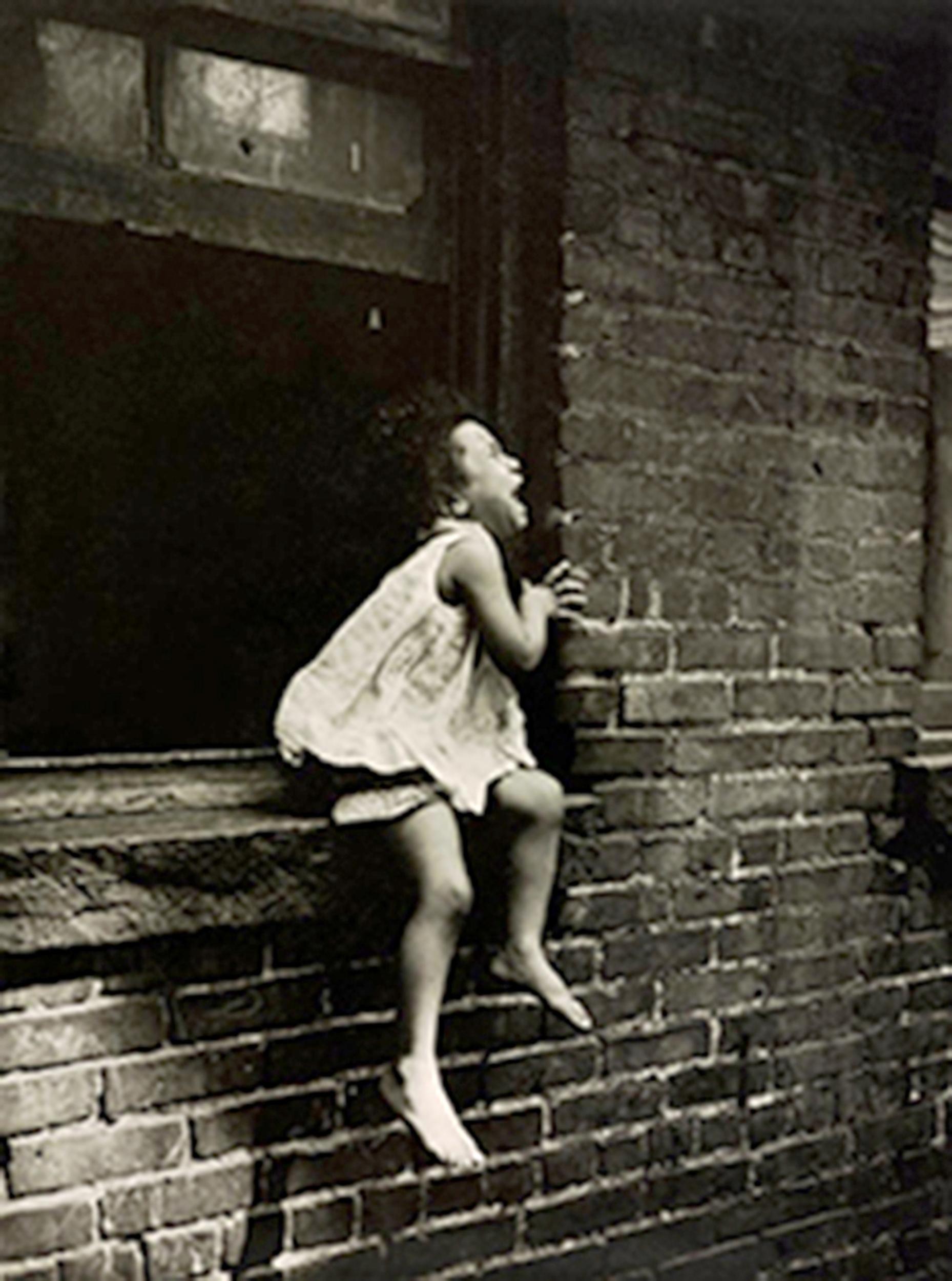

Parks finished his assignment, largely ignoring the instruction to focus on the father and his political leanings. Instead, he focused on Flavio and on Flavio’s brothers and sisters. He kept a diary of his days in the favela. He was there when the children woke up. He photographed them in the rudimentary kitchen. He even took them by car to Copacabana. The famous beach was just 15 minutes away, but they had never seen it, and Parks recorded their euphoric responses.

Each night he left the favela and returned, uneasy, to his room in Copacabana’s upscale Hotel Excelsior. Parks had grown up the youngest of 15 children and the victim of racist bullying. Now a parent himself, he couldn’t help but empathise with Flavio. He wrote of being “filled with confusion and guilt during my final days in Catacumba. Flavio, like thousands of other children, would die ... I could not help compare the good fortune of my own children with the fate of these others”.

Three weeks after he arrived, Parks flew back to New York. “I said goodbye to Flavio and the family today,” he wrote. “‘Gorduun, when do you come back?’ [Flavio] asked. ‘Oh someday soon,’ I lied.”

But it wasn’t a lie.

Park’s photos appeared in the 16 June 1961, issue of Life under the heading, “Freedom’s Fearful Foe: Poverty.” You can see them in the first room of “Gordon Parks: The Flavio Story”, a riveting show at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles. The second, third and fourth rooms uncover the bewildering events that the photo essay set in motion.

Parks belonged to a generation of photojournalists whose work could get massive exposure. He said he wanted his work “to draw people’s attention to the problems they show” and to play a role in effecting change. An admirer of President Kennedy, he hoped that the new president’s youth and progressive policies would have positive results. But he had seen firsthand, too, that the United States lacked credibility in Latin America. If it wanted to solve problems there, he realised, the United States needed first to “clean up its own yard”.

Intimate, observant, poetically suggestive, Parks’s photos of Flavio and his family were the work of an artist. “Far from condescending, they utterly personalised ... and made intimate the tragedy of poverty,” Paul Roth wrote in the show’s terrific catalogue. (Roth’s essay is the source of much of the information in this story). They “punctured”, he said, Life magazine’s “conception of indigence as an abstract lure to an ideological foe” – communism.

Parks’s photo essay was one of the most influential Life ever published. It provoked an enormous response from readers, who sent thousands of letters and unsolicited donations. When Life published excerpts from the letters in a subsequent issue, under the headline “A Great Urge to Help Flavio”, it included an appeal for more donations, which Life said it would use to move the Da Silvas to a modest new home and to seek medical treatment for Flavio.

Parks flew back to Rio on 28 June to deliver the message. To his relief, Flavio’s parents needed no persuading to release Flavio to the care of a hospital in Denver. “Keep him in hospital as long as necessary but please bring him back cured and well,” his father said.

At Parks’s hotel, Flavio had his first-ever bath (“The water was black,” Parks noted) and donned new clothes that Parks had bought for him. A team of people worked on getting Flavio a visa and on finding a suitable home for his family.

The day came for the family to move out of Catacumba. Their story had spread, and a crowd gathered to watch. Parks, who was there to document the day, remembered a woman grabbing his shoulder and saying: “What about us? All the rest of us stay here to die!”

That same night, Parks and Gallo drove Flavio to the airport, and all three flew to the United States.

In Denver, Flavio was treated at the Children’s Asthma Research Institute and Hospital. Life photographer Carl Iwasaki documented the first days of his life in Denver, including visits to the hospital, first days at school and a visit to an amusement park. The photographs of Flavio 2.0 – designed above all, it can seem, to make America feel good about itself – were published in the magazine’s 21 July issue.

The repercussions of this intervention went beyond Flavio and his family. Editors at O Cruzeiro, an illustrated weekly in Brazil, took umbrage at Parks’s photo essay (which had appeared in a Spanish-language version of Life, distributed throughout South America).

O Cruzeiro had Brazilian nationalist leanings. Its editors objected to a high-circulation US magazine with an explicit political agenda coming to Brazil to point out problems that had not been solved in its own country.

Their response was impudent, blunt and charged with chutzpah. They sent a photographer of their own, Henri Ballot, to New York City. After photographing the streets of impoverished communities in Spanish Harlem and on the Lower East Side, Ballot homed in on Puerto Rican immigrants Felix and Esther Gonzalez. They lived with their six children in a dilapidated, rat- and cockroach-infested tenement building on Rivington Street.

Ballot’s photographs were published in the 7 October 1961 issue of O Cruzeiro. They revealed living conditions every bit as desperate as those of the Da Silvas. One photograph shows a child sleeping with three enormous cockroaches on his bare skin. Another shows a child with a bandage covering a rat bite on his forehead. O Cruzeiro rammed home its point by publishing some of Ballot’s New York images with insets showing Park’s original Rio images.

The two magazines went to war, each accusing the other of staging its photographs – of, effectively, manufacturing “fake news”. And, as happens routinely in any polarised media environment, real people enduring real predicaments were reduced to pawns in a propaganda war.

Meanwhile, in Denver, the transition proved tricky for Flavio. He struggled at school. But things slowly settled down. He learned English, adapted his behaviour and spent weekends with a Portuguese-speaking family, the Gonçalves. Over time, he had less and less contact with his family back in Rio. And when the treatment neared its conclusion after two full years, he was desperate to remain.

He begged Parks and the Gonçalves to adopt him. Instead, in July 1963, Flavio returned to Rio, where he stayed briefly with his family before being sent to a boarding school in São Paulo. The schooling was arranged and paid for by Life.

Parks maintained contact with Flavio after the boy’s return to Brazil, and in 1978, he published a book (Flavio) about the experience, which brought him back to Rio to gather material. Parks also visited in 1999 to film a documentary (Gordon Parks – Half Past Autumn). In each of those trips, the journalist saw that his subject’s struggles with poverty had never really abated.

“As a photojournalist,” Parks wrote, with more than a tinge of melancholy, “I have occasionally done stories that have seriously altered human lives. In hindsight, I often wonder if it might not have been wiser to have left those lives untouched, to have let them grind out their time as fate intended.”

Flavio himself, now retired from his job as a security guard, later reflected on the fact that, thanks to Parks, “people know more about my life than I do. I’m glad that I’m alive as a result ... (But) this story never made me feel either better or worse than anyone else.”

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments