The exhibition that uses women’s hosiery to tell a story

‘Gossamer’ brings together work by 22 artists who have used stockings as a material to explore race, gender, femininity and subversion, writes Rachel Felder

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Women’s hosiery isn’t something you’d necessarily expect to find hanging in an art gallery. Nor would you usually think of tights as thought-provoking.

But Gossamer, an exhibition at Carl Freedman Gallery in Margate, shows that nylon pantyhose and garter-held stockings can be a rich source for artists.

Gossamer brings together work by 22 artists – including Louise Bourgeois, Sarah Lucas and Man Ray – who have made art using stockings as subject matter or as a material instead of, say, paint or steel. The show touches on themes of race, gender, femininity and subversion.

Zoe Bedeaux, the show’s curator, is a performance artist, poet, and former stylist for photographers such as Juergen Teller. She has had little experience curating exhibitions, but in her other work, Bedeaux frequently explores the semiotics of fashion. She was interested in “the conversation of clothes,” she said in a recent interview at the gallery.

Carl Freedman, the gallery’s founder, acknowledges: “It’s not like we’ve hired somebody from the Tate.” Last autumn, he says, he approached Bedeaux, who he’d known for several years, about the possibility of putting together a show; she had already conceived a theme for an exhibition, and even had the name ready, Freedman says.

The show’s artists come from countries including Belgium, China, Japan, Mexico and Poland, as well as Britain and the United States. The works range from an elegant 1945 Man Ray photograph that depicts a woman’s head covered in gauzy, veil-like nylon, to the Iranian artist Shirin Fakhim’s jarring, full-size sculpture of prostitutes in Tehran made, in part, from stuffed tights.

“I love that disparity and that breadth,” Bedeaux says. “You’re looking at these things and you’re always back to, ‘Oh my God, these are tights; these are stockings.’ And then you’ve got all these other dialogues going on.

“Tights are the base material,” she adds, “but this show is not about tights.”

“Nude” pantyhose, for example, can been seen as a symbol of racism, since, until recently, their shades bore little resemblance to the complexions of women of colour. Bedeaux, who is of Caribbean descent, says that she remembers an aunt whose legs seemed to be a different hue from her body when covered in tights in a “nude” shade called American Tan. “They looked prosthetic,” Bedeaux says. “It was a totally artificial colour.”

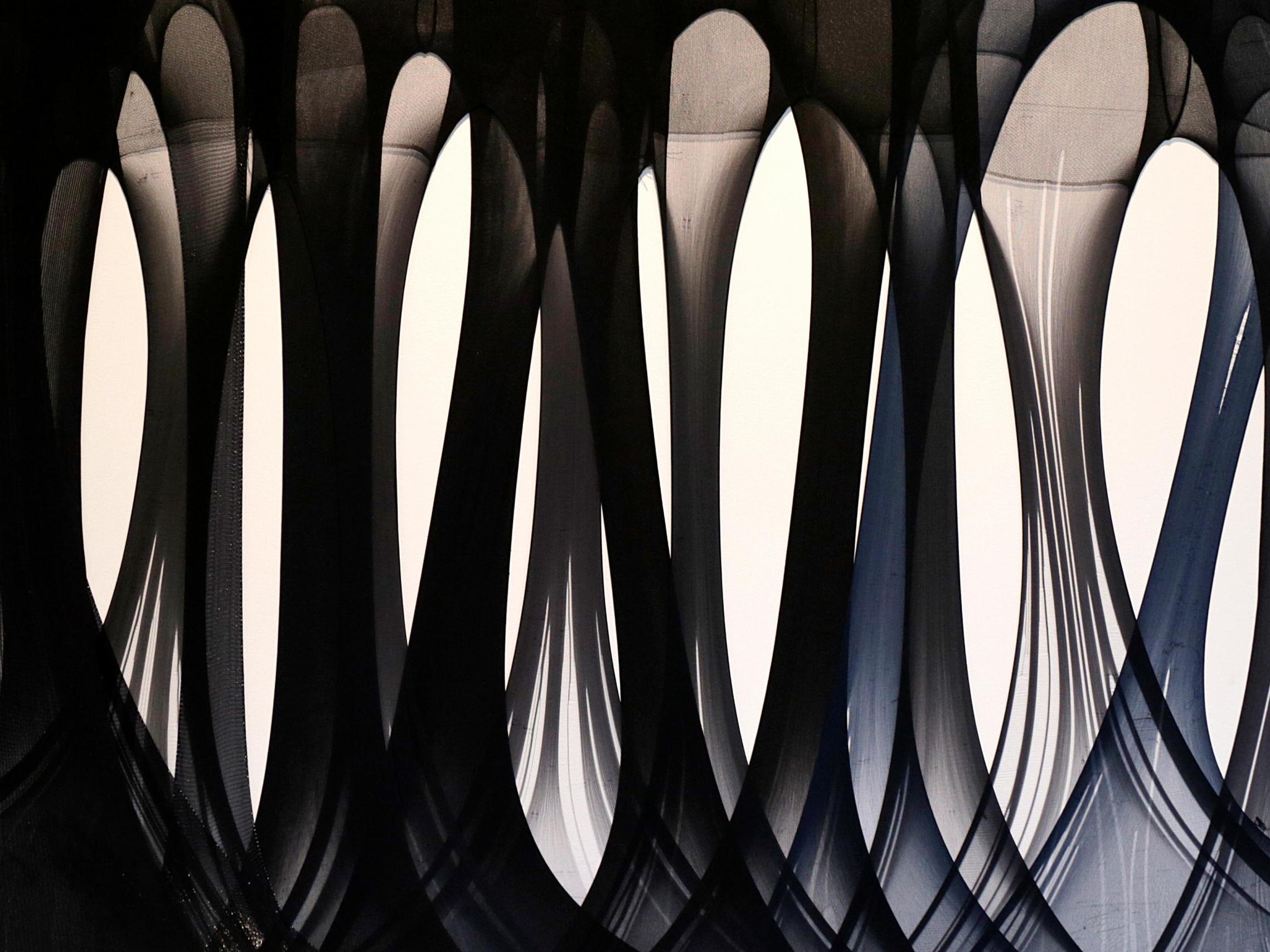

Gossamer includes a print from a series called American Tan by the British artist Gary Hume: an image of a headless woman with splayed legs in that neutral shade; the figure seems hardly human. Another work, Enam Gbewonyo’s The Oculus-The Third Eye is an installation of intertwined swatches of nude pantyhose arranged in a circle on the floor; they are mostly quite fair, with the few dark options in a flat brown that excludes the many nuanced hues of skin of colour.

Women’s hosiery is, of course, an emblem of femininity: its physical qualities – stretchy until it inevitably rips apart – underline the notion of women as both strong and fragile. It’s used in that context in several pieces in the show, such as Not One More, in which the artist Maria Ezcurra has hung several dozen pairs of faded and worn tights on a circular rack to represent women who were violently murdered in Mexico in the late 1990s.

The association with femininity makes images of men wearing hosiery all the more transgressive. There are pieces along those lines in the show as well, like a stark image of a male cross-dresser in back-seamed stockings by the artist Ulay, who Bedeaux says was “a gender pioneer.”

Bedeaux says her decision to include works by male artists in the show had initially surprised Freedman. “He thought it was going to be about women,” Bedeaux says. “That’s my interest, to see how men would use the material or interpret what’s their vision, and what’s behind their association with tights and stockings.”

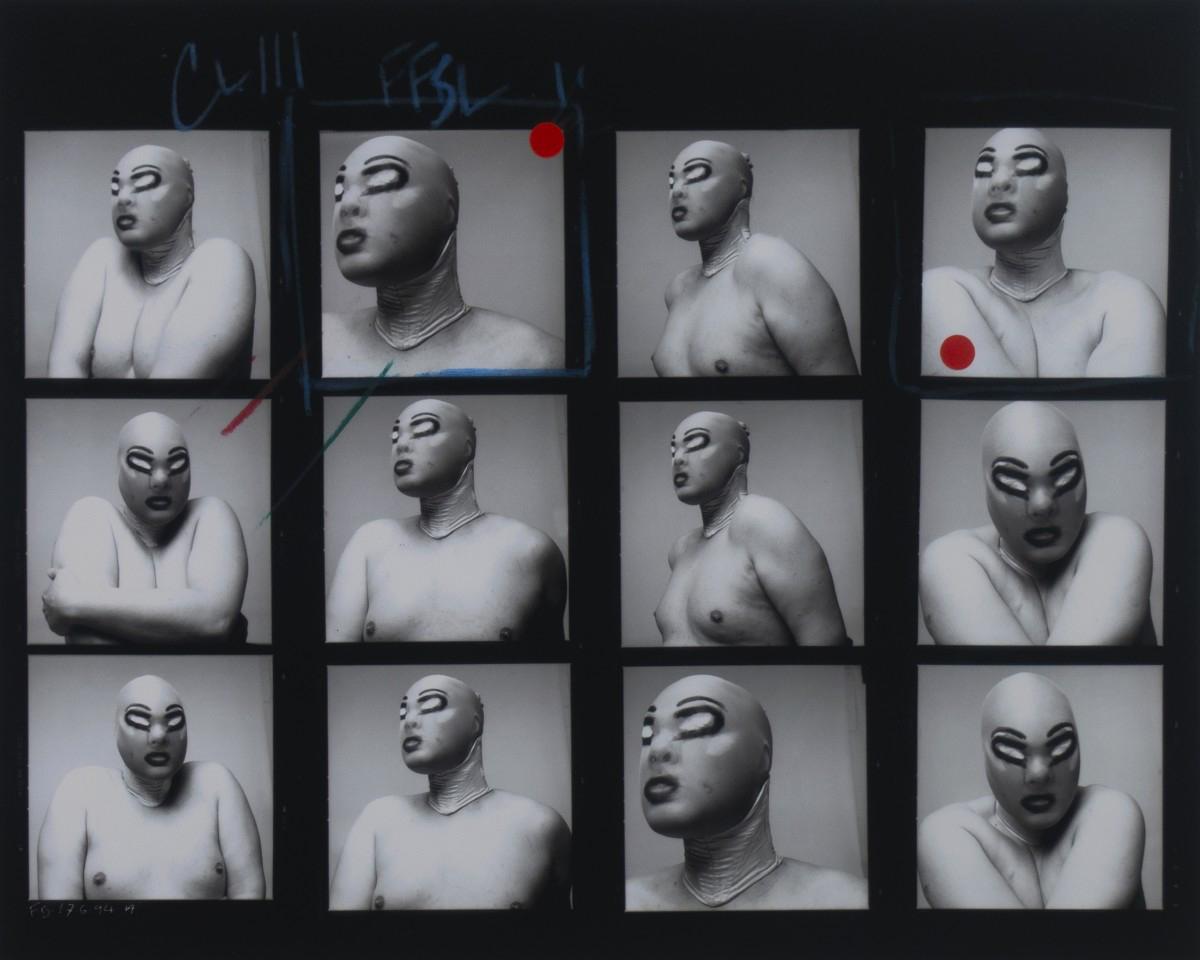

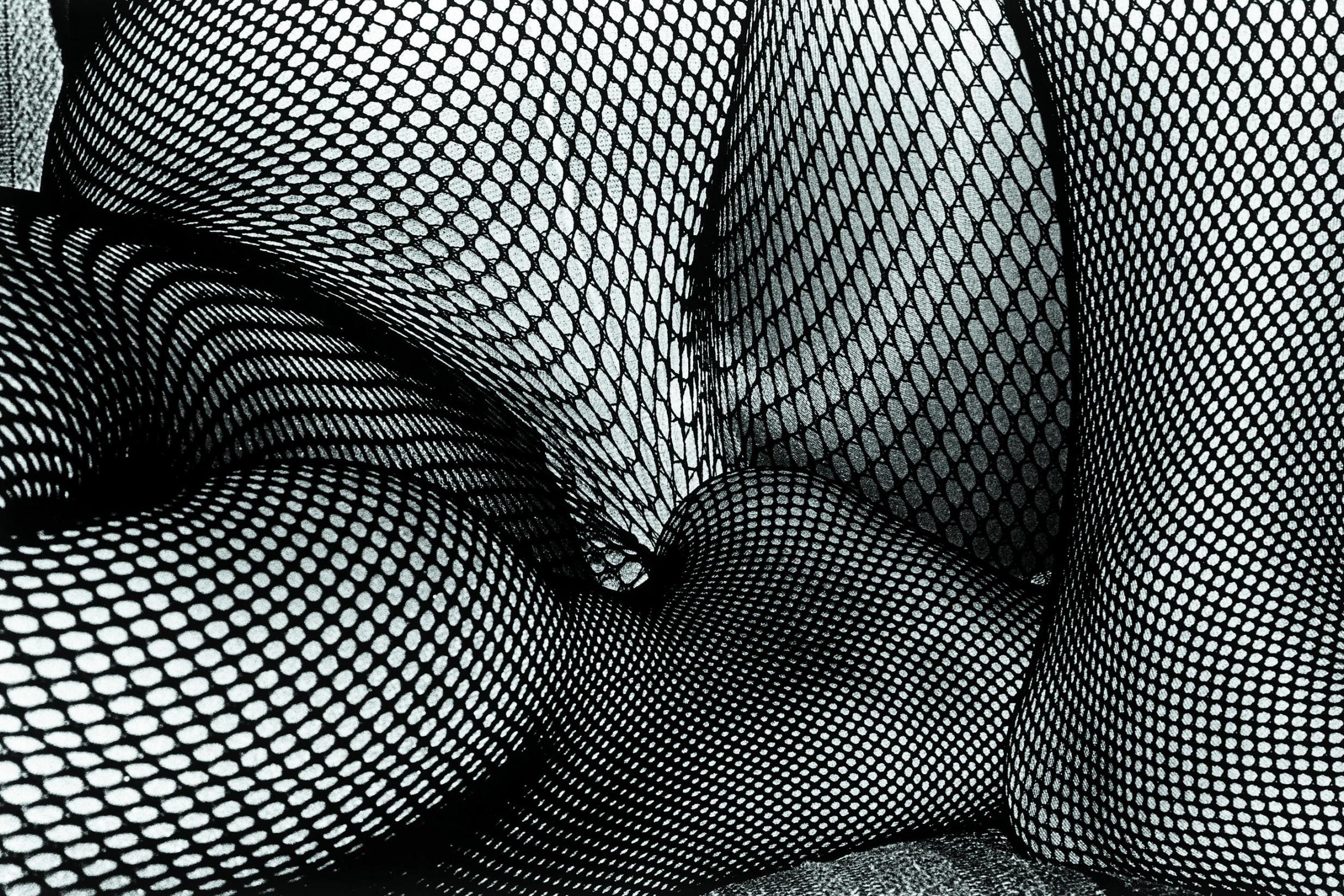

Some of those associations are sexy, erotic and, occasionally, fetishistic. There’s a suggestive intimacy to images of sheer stockings that makes some of the show’s pieces – like a pair of Pierre Molinier photographs with multiple pairs of stockinged legs in copulating poses – seem voyeuristic. Tights can be worn subversively, too: the performance artist Leigh Bowery did that, for example, in two photographs by Fergus Greer, included in Gossamer, in which his head is covered in a stocking, like a nylon balaclava, and exaggerated facial features drawn on in make-up.

The inclusion of provocative images in the show was deliberate, Freedman says. Others include Elmer Batters’ 1969 photograph of a woman lying on a park bench, her stocking-clad legs in the air, panties exposed, suggesting behaviour conventionally reserved for the bedroom rather than a public place.

Bedeaux says she wants people to think about the depth in what is otherwise just an everyday item. “This has been a benign object, and everyone’s wearing it,” she says. “But when you break it down,” she adds, “it’s not.”

“Gossamer” runs until 15 December at Carl Freedman Gallery in Margate; carlfreedman.com

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments