For tens of thousands of soldiers, the First World War didn't end on Armistice Day

The modern narrative of a neat and tidy end is a myth, says Jane Fae. When news reached commanders some decided not to risk lives for territory they could walk into tomorrow. Others carried on until the last second

At the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month 2018 we commemorate the 100th anniversary of the “end” of the First World War. Yet this is at best an approximation: at worst the deliberate obfuscation of an awful truth, which is that the war did not end all at once or even in that month. Rather, it sputtered on for months, and in some places years. Worse, even as an end was in sight, commanders continued to send thousands of young men to their deaths for motives quite disgraceful to modern sensibilities.To gain a few yards’ ground. To avenge a defeat. To secure a medal or a promotion. To win access to a hot bath…

The modern narrative of a neat and tidy end is myth, alongside the neat and tidy History 101 version of the First World War. Kicked off August 1914. Over by Christmas. Or not. Football in no-man’s land. Ill-fated Gallipoli campaign, 1915. Ill-fated Somme offensive, 1916. Asquith resigns. Russia crashes out, as the US joins in, 1917. Ludendorff Offensive, 1918. Germany exhausted. The end: November 1918.

Sorted. A little messiness around the edges can be shunted off to a solitary essay entitled “Lions led by donkeys: discuss”.

Except it didn’t start all at once: the principal players spent the first three months or so after August 1914 sorting out just who was declaring war on whom – and as the war continued, countries dropped in and out, like guests at a cocktail party. Italy waited until May 1915 before declaring war on Austria-Hungary: a few weeks later, little San Marino followed.

Honduras waited until July 1918, by which time it was pretty clear which way the wind was blowing. This act of solidarity with the US, which had declared war a year earlier, did not end well for Honduran president Francisco Bertrand. It upset the large number of Germans then living in country and in 1919 they retaliated by joining with his political opponents and booting him out of office.

Countries negotiated a peace at different times, blundering out of the war as their economies buckled. Governments fell. The old order, across Europe, changed.

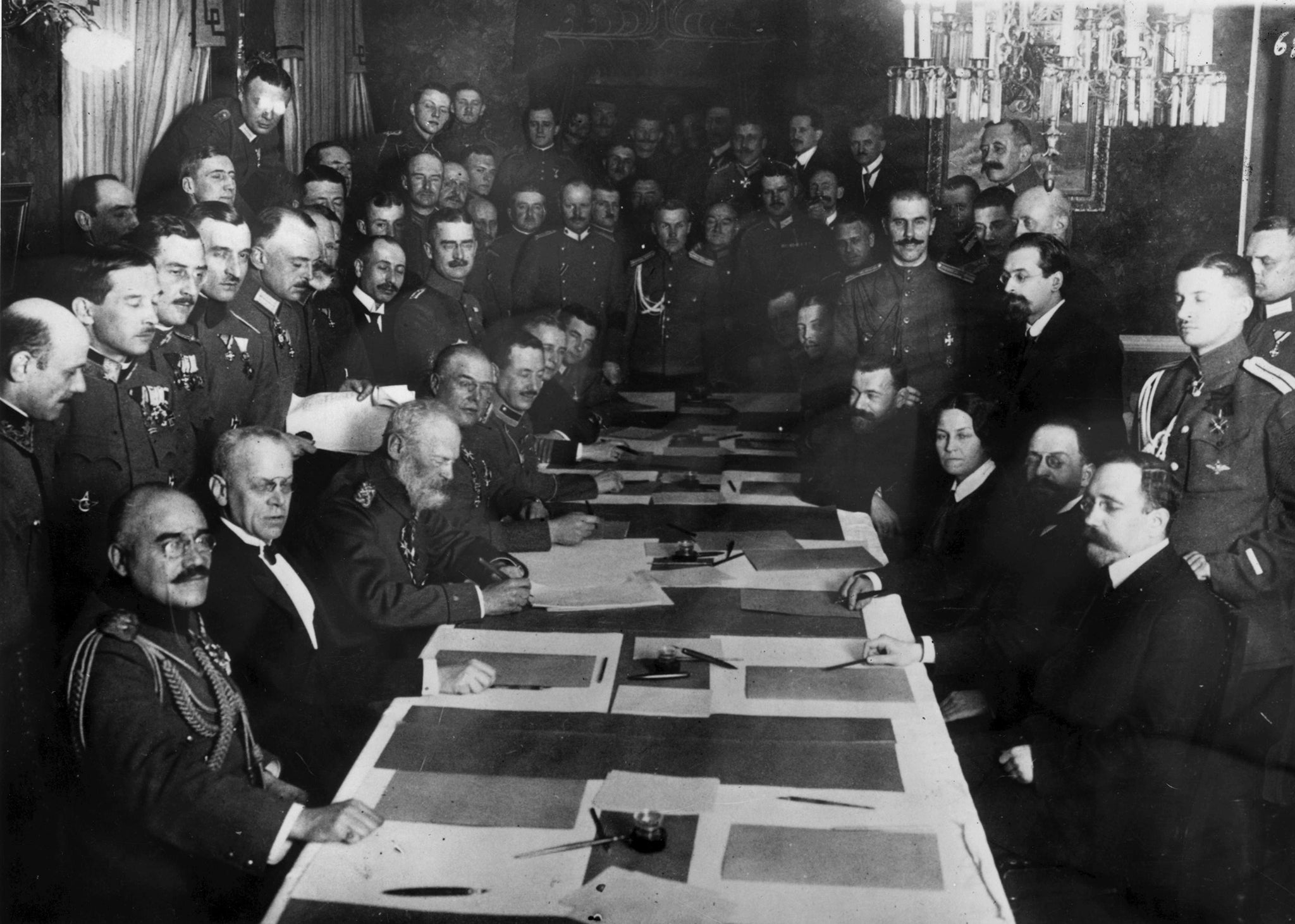

Russia was the first and most significant departure. A moderate revolution in March 1917, the result of economic collapse and food rationing, swept away centuries of tsarist tradition. And when the moderates failed to deliver the promised peace a second communist revolution led to a hasty armistice and exit in December 1917.

That knocked out Romania, which had first entered the war on the allied side in August 1916. But without regional ally Russia, it had little chance of resisting Germany. In May 1918 Romania agreed the Treaty of Bucharest, in theory ending their part in the war. However this was never ratified, was denounced by the Romanian government, and Romania re-entered the war in October 1918.

Almost as he fell, the gunfire died away and an appalling silence prevailed

Bulgaria called time on 30 September 1918. Turkey and Austria-Hungary concluded an armistice within days of each other, on 30 October and 3 November 1918 respectively; both were exhausted and could no longer continue to prosecute the war. For both, the end of the war meant the end of historic empire: immediately in the case of the Austrian Hapsburg Empire; over the next couple of years for the Turkish Ottoman Empire.

The writing was on the wall for Germany. From the beginning, their nightmare scenario had been the possibility of having to fight on two fronts. They therefore devised the Schlieffen Plan, which envisaged a swift knockout blow against France in the west before turning to deal with Russia in the east. It almost worked: its failure meant stalemate on the western front and four long years of bloody attrition.

The collapse of Russia in 1917 was good news. This was balanced by the entry of America into the war in April of that year. Still, if the Germans could deliver a knockout blow to France and Britain before the Americans deployed in any numbers, there was still hope.

So in March 1918 they tried one throw of the die: their “Spring Offensive”. Once again, it seemed as though they might succeed: but the allies held on. In July 1918, the German advance was halted; 8 August, recorded as the “black day of the German army”, followed, and now the end was in sight. Across the front, the allies gained ground, sometimes miles at a time, as the war emerged from the trenches.

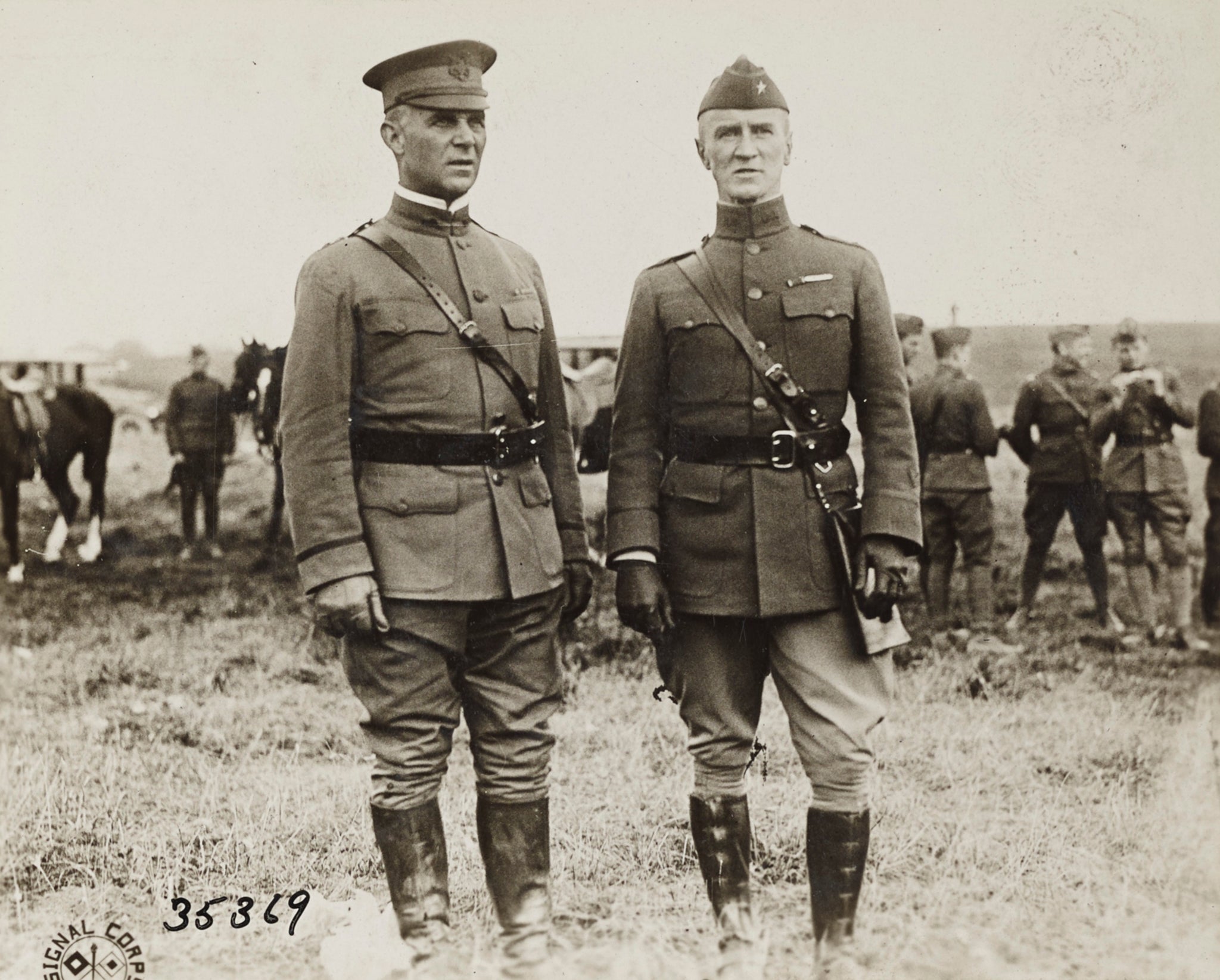

US troops – known as “doughboys” – were now arriving in France at the rate of 10,000 a day. An insistence on operating independently by their commander general John Pershing meant they took higher casualties than they should have. But nothing could change the fundamental narrative.

The German army, exhausted and starving, was starting to fall apart. Back home, revolution was brewing. German sailors at Wilhelmshaven and Kiel mutinied en masse. It was time to salvage whatever could be salvaged. The army must return home to prevent the breakup of their country: peace, at any price, was imperative.

On Thursday 7 November, a number of cars bearing white flags approached the French front line near La Capelle. This was a civilian peace delegation despatched by the German government and led by Matthias Erzberger. The delegation was escorted behind allied lines to a railway siding in Compiegne, and the personal train carriage of Marshal Foch, supreme commander of the allied armies.

Foch, though, was in no mood to compromise. France had suffered some 6 million casualties, including 1.7 million killed. He himself had lost a son and son-in-law. His first words to the delegation were sharp: “What do you want from me?” He made clear there would be no negotiation.

A meeting was arranged for the next day: after this the Germans had 72 hours to agree terms, which were harsh in the extreme. Erzberger’s suggestion of an immediate ceasefire was refused. Foch gave little: yet so desperate was his government that Erzberger was ordered to accept any terms.

To modern sensibilities, this refusal to countenance ceasefire with talks appears cruel. On 3 November, the Austrians agreed a ceasefire to come into effect the next day. But the Austro-Hungarian high command instructed all forces to stop fighting the same day.

2,250

Number of troops dying per day on western front

On the western front, 2,250 troops were dying, on average, every day. On 9 November Canadian forces, under the command of General Sir Arthur Curry launched an attack on Mons, which continued through to the town’s capture on 11 November. Casualties were light: just 280 killed and injured. Still, suspicion remains that this action was motivated less by strategic considerations than by the fact that Mons was the site of one of the allies’ first major defeats of the war.

Curry was not alone. Many, including US general Charles Summerall, who ordered his men across the Meuse river against machine gunners at midnight on 11 November, were determined to continue the fight to the last moment.

If such wilful disregard for human life is hard to understand, what followed, in the hours after the armistice was signed, cannot do other than outrage. The armistice document was signed at 5am on 11 November (or 5.03am or 5.10am depending on source) and due to come into effect at 11am.

This was to allow time for the news to percolate across the front and to notify the people back home. By 5.40am celebrations had begun in capitals around the world. In London, Big Ben was rung for the first time since the start of the war: in Paris, gas lamps were lit; and in New York people came out on to the streets to bang pots and pans and celebrate.

Yet for tens of thousands of soldiers on the western front it was business as usual for some hours yet. Local commanders were informed that fighting would stop at 11: but it was for them to decide what to do next. Some decided not to risk lives for territory they would walk into tomorrow. Others carried on until the last second.

According to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) 863 Commonwealth soldiers died on 11 November 1918. As for all of the figures cited here, this includes those who died on that day from wounds received in prior actions – but not those who died subsequently as result of actions on that day. The CWGC records the last British soldier to die in World War One as Private George Edwin Ellison of the Fifth Royal Irish Lancers, killed at Mons at 9.30am, just 90 minutes before the ceasefire.

The last French soldier to die was Augustin Trebuchon from the 415th Infantry Regiment. He was a runner, killed by a single shot at 10.50am while delivering a message to fellow soldiers informing them of the ceasefire. At least 75 French soldiers died on 11 November, though for reasons unknown – perhaps to spare politicians scandal - their graves state 10 November.

The last Canadian and last Commonwealth soldier to die in the First World War was Private George Lawrence Price of the Canadian infantry, killed at Mons at 10.58.

American casualties on the last day of the war were especially high: at least 3,000, which exceeded total US losses on D-Day in 1944. This may be attributed both to their recent arrival and fighting spirit not yet blunted by the horror of war, as well as the much-publicised view of their commander, General John Pershing, that only severe military defeat of the Germans would “teach them a lesson”.

Pershing saw the terms of the armistice as being soft on the Germans. Therefore, he supported those commanders who wanted to be pro-active in attacking German positions – even after the armistice had been signed.

General Summerall’s decision to order his troops across the Meuse resulted in the US marines taking over 1,100 casualties when, just a few hours later, they could have crossed unhindered and with no casualties. After the fighting was over, it is recorded, Summerall visited the sight of the battle to have his picture taken – and then promptly drove off again.

One disturbing episode was the commitment to battle, in the last hours of the war of the US 92nd. This was a unit formed from black draftees run for the most part by white officers. Just another bad decision? Perhaps: except that racism within the US army was legendary. Black units were rarely used when white units were available, reflecting sentiments such as those of General Robert Bullard, who wrote in his memoirs in 1925: “Poor negroes! They are hopelessly inferior.”

Whatever the motives, the 92nd acquitted themselves well, taking 190 (unnecessary) casualties in the last hours of the war. For sheer awfulness, though, nothing touches the decision of General Wright to order the 89th forward to take the town of Stenay on the morning of 11 November. Because, he explained, he had heard there were bathing facilities in the town and he wanted his men to have access to hot water.

It is a shame we can’t go in and devastate Germany and cut off a few of the German kids’ hands and feet and scalp a few of their old men

Stenay was the last town captured on the western front, at a cost of over 300 casualties. Then there was the fate of the 81st. One regimental commander ordered his men to take cover during the last hours. His orders were countermanded and with 40 minutes of war to go, they were ordered to “advance at once•. Result: 461 casualties, including 66 killed.

Official figures suggest 10,944 casualties on the last morning of the war, including 2,738 dead. Yet the horror – and the pity – of those hours lies not just in the headline figures, but also in the poignancy of individual stories.

The last American soldier killed was Private Henry Gunther of the US 313th. With 16 minutes to go, his unit was ordered to take a German machine gun post: their commander was of the view there should be no let-up until 11am. Gunther followed orders. The machine gunners waved him back. But Gunther went on. The machine gunners fired: Gunther died – at 10.59am. According to his divisional record: “Almost as he fell the gunfire died away and an appalling silence prevailed.”

A last entry by one German private in his diary expresses amazement that after 50 months at the front line he would be coming home unwounded. He did not survive the onslaught from US troops who attacked, minutes later. Another, an American infantryman, wrote home to his love to say they would be married when he returned. He never did.

The very last casualty of the war was, likely, a German who approached a group of Americans shortly after 11 to tell them his troops were pulling back and they could have the house he and his men were vacating. But no one had told them that the war was over. So they shot Tomas as he walked towards them. Inevitably, people have asked why.

The reasons were mixed. In part, the desire to continue fighting reflected the strategic view of some commanders. By one calculation, a ceasefire on 8 November would have spared 6,624 lives and 14,895 maimed, burned, disfigured casualties. Yet there was widespread belief, shared by Pershing, that Germany must not just lose, but be seen to have lost or another war might follow.

As he himself said at the time: “If only they had given us another 10 days.” That same sentiment is expressed even more graphically by one artillery captain, a certain Harry S Truman, who wrote home to his fiancee: “It is a shame we can’t go in and devastate Germany and cut off a few of the German kids’ hands and feet and scalp a few of their old men.”

Unpalatable as it may sound, there was some justice to Pershing’s view. Almost as soon as the war concluded, the “stab-in-the-back” myth began to propagate – and it formed a major plank underpinning the rise to power of Adolf Hitler.

There were grounds for continuing the fight until an armistice was concluded. However, the idea that the allies could have marched on to Berlin was dismissed by General Sir Frederick Maurice’s post-war account of the closing period of the war, The Last Four Months, published in 1919.

Yes, he notes: there was a will to carry on. However, he also argues allied supply lines were over-extended and that, combined with the fact that almost all transport infrastructure between the front lines and Berlin had been destroyed or sabotaged by the Germans meant significant advance was no longer possible.

Pershing’s failure to issue any direct order to generals to stop fighting is another matter There was no benefit to be had from six hours more fighting: and thousands paid for that dereliction with their lives.

Beyond the strategic, there was a wider callousness, indifference, bloody-mindedness, summed up by the words of a British corps commander in respect of the Somme two years earlier: “The men are much too keen on saving their own skins. They need to be taught that they are out here to do their job. Whether they survive or not is a matter of complete indifference.”

In the US, public opinion demanded explanation. There was a congressional inquiry into why so many died after peace was agreed: despite Pershing’s claim to have been doing no more than follow Foch’s orders, an initial conclusion held that needless slaughter had occurred, and that decisions had been made by men whose own lives had never been put at risk. But then politicians condemned the report as unpatriotic: it fell foul of party politics and by March 1920 all suggestion of needless loss was removed.

And after all that, the war did not end on 11 November. On the western front, the fighting stopped. And the conditions of armistice meant it very unlikely they would ever resume. But armistice was re-enacted several times in the months that followed. And besides, the war (with Germany) did not end officially until the Treaty of Versaille, signed on 28 June 1919, the official end date of the First World War.

The official tally for the First World War, as this conflict eventually came to be known, was 40 million military and civilian casualties: that's 20 million dead and 21 million wounded. But that tells but a part of the story.

Elsewhere, the Great War issued forth in further wars, especially in Eastern Europe, leaving hundreds of thousands more dead and injured. The wholesale destruction of infrastructure left entire populations vulnerable to further natural attrition from disease and starvation. 1918 was marked also by the outbreak of “Spanish Flu”, which eventually killed over 50 million people worldwide: and while the exact contribution of War to this outcome remains unmeasurable, it undoubtedly played a part.

For those wounded on the last day – and before – there would be weeks and months of suffering still. Many would carry the scars for life, as permanent disfigurement or disability. As for Matthias Erzberger, who signed the Armistice and helped bring an end to so much suffering: he was denounced as a traitor, and in August 1921, while walking in the Black Forest, he was assassinated by two former navy officers.

If you would like to read more about the events of the last day of World War One, read: Eleventh Month, Eleventh Day, Eleventh Hour: Armistice Day, 1918 World War and Its Violent Climax, in paperback, by Joseph E Persico

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Eleventh-Month-Day-Hour-Armistice/dp/0375760458

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments