Archaeology from the sky: how satellite and laser technology can reveal ancient secrets

Remote sensing has brought a new golden age for the field in which the amount of material coming out of the ground will soon be greater than the museum space available to store it, writes Sean T Smith

These days, if you want to search for lost civilisations, there’s no need to machete your way through jungles like Indiana Jones, you simply need to turn on your laptop.

Remote sensing technology has transformed the field of archaeology. Satellite imaging and aerial survey tools like Lidar have removed so much of the guesswork, traditional excavations are often no longer necessary.

Now that we can penetrate the Earth’s surface to reveal traces of our ancestors’ hidden homes from thousands of miles away, archaeologists tend to only embark on traditional digs if they already know what they’re going to find.

By analysing high-resolution images from Nasa satellites with the infrared part of the light spectrum, self-proclaimed space archaeologist Sarah Parcak pioneered a way of “CAT-scanning” the planet to pinpoint sites of potential archaeological interest.

As a professor of anthropology and director of the Laboratory for Global Observation at the University of Alabama, Parcak and her team detect subtle differences on the Earth’s surface that are invisible to the human eye at ground level.

When analysing fields and woodlands, for example, they discovered that patches where the vegetation was slightly lighter in colour merited closer inspection. Focusing on fainter shades of chlorophyll was highly effective because it indicated the impaired, shallower roots that you’d expect to find wherever manmade structures are hidden just below the surface.

Such techniques have allowed Parcak and her team to locate hundreds of sites of archaeological value in Egypt, such as mapping the streets of ancient Tanis (fictitiously portrayed as the resting place of the ark in Raiders of the Lost Ark), and in doing so has helped popularise archaeology as a citizen science.

In 2016, by launching the online platform GlobalXplorer, Parcak’s team managed to map the whole of Peru by crowdsourcing the work of analysing satellite images out to an armchair army of amateur archaeologists.

With the stated aim of “revolutionising how modern archaeology is done altogether by creating a global network of citizen explorers”, GlobalXplorer has mobilised 900,000 enthusiasts and claims to have tracked down many sites of major importance.

It was wonderful entertainment but I didn’t find very much. We had to just go by bumps in fields and almost every field has a bump

As an archaeologist and remote sensing specialist at Newcastle University, Dr Louise Rayne has found the speed with which satellite image analysis has transformed archaeology as an academic discipline quite disorientating.

“When I stop and think about it, I’m shocked,” she tells me. “When I started learning how to use these approaches in about 2009, there were only one or two sources of free satellite data of the kind which can be used for automated mapping. But now, there are so many other satellites, and the use of cloud computing and high-performance computing allows us to process thousands of images.”

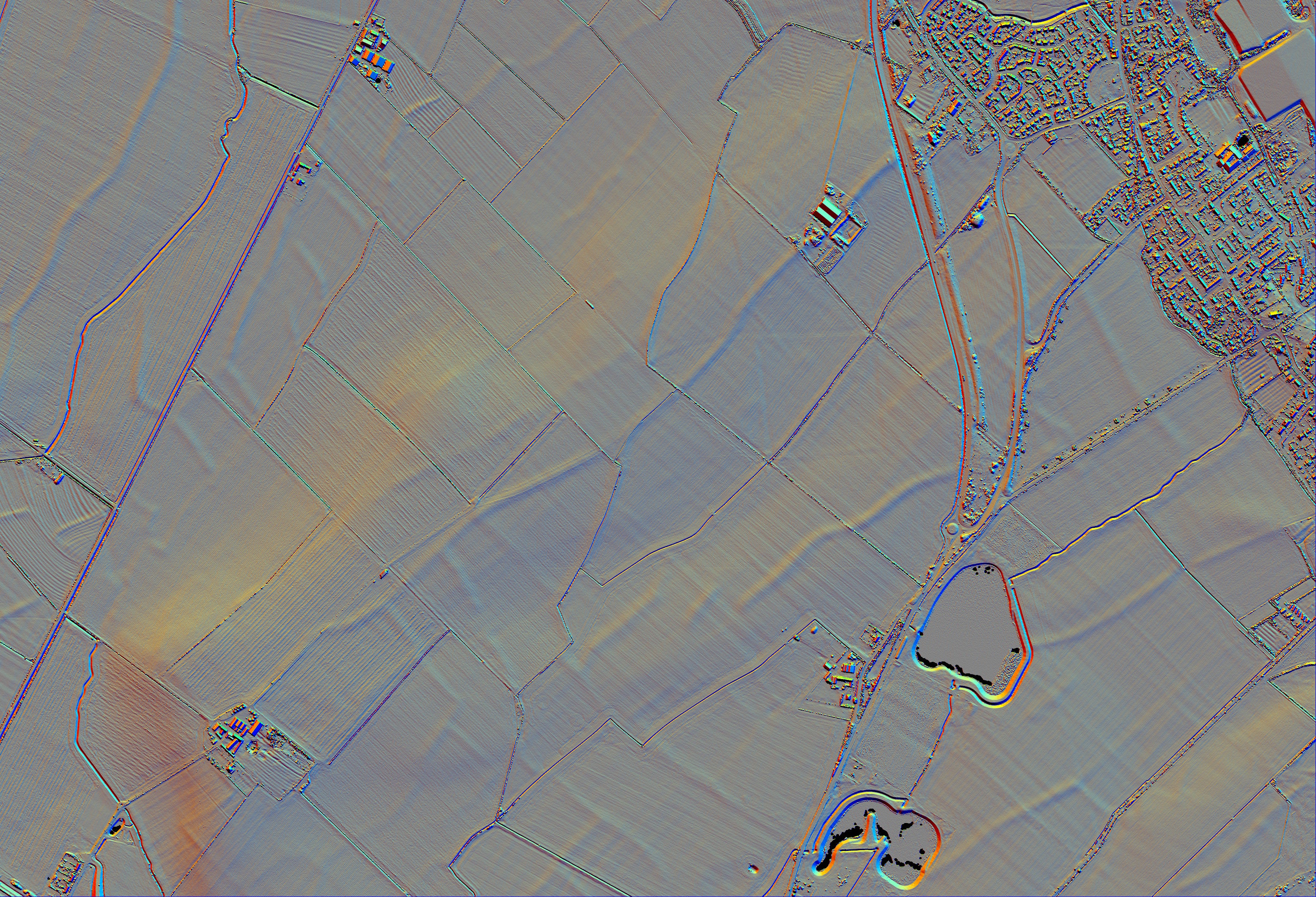

But Lidar technology has had an even more transformative effect on archaeology than satellite imaging. Lidar – short for light detection and ranging – is a laser system flown from an aircraft that can build an accurate three-dimensional model of the ground, mapping its features in high-resolution detail.

Ever since Historic England – the government organisation responsible for identifying and protecting our hidden heritage – first used Lidar to map the area around Stonehenge in 2005, it has been peeling back layers of English landscape to discover lost Roman camps, Neolithic henges and Bronze Age cemeteries.

According to Matthew Oakey, head of Historic England’s Aerial Survey team: “Lidar is one of the most significant developments in aerial archaeology in the last 15 to 20 years.”

Because Lidar uses hundreds of thousands of light beams, it can penetrate gaps in even the densest forest canopies, he explains. “It can be processed to virtually remove surface vegetation, revealing the landscape below. Thousands of new sites have been discovered in wooded areas that we were never previously able to explore from the air,” says Oakey.

Although over the centuries Roman roads will have been ploughed away and might now only be a few inches high, Lidar is sensitive enough to detect those ridges

Compared to the rest of the world, the UK is already one of the most closely Lidar-mapped countries because the government has been using it since 1998 as part of its flood defences work.

In addition to analysing the masses of data that was made freely available to download by the Environment Agency in 2015, Historic England routinely carries out aerial reconnaissance and is now even able to deploy Lidar using drones to uncover the nation’s pre-history.

“Lidar is particularly well-suited to recording archaeology in upland landscapes where remains are often better preserved due to the lack of modern ploughing. In these cases, Lidar has been an essential tool for studying the field systems, trackways and settlements dating back to the prehistoric period. A number of new Roman camps and roads have also been discovered,” says Oakey.

David Ratledge, a retired road engineer and amateur archaeologist, is responsible for locating many of those Roman roads.

With little to go on other than hedge lines and the assumption that old parish boundaries would be a logical place to look, Ratledge spent over 40 years looking for lost Roman roads with only limited success.

“It was wonderful entertainment but I didn’t find very much. We had to just go by bumps in fields and unfortunately almost every field has a bump so you’d fool yourself into thinking that you’d found something,” he tells me.

But the environment agency’s mass release of Lidar data in 2015 changed all of that, due to a serendipitous feature of the Romans’ civil engineering.

It’s a little like Minecraft but in much higher resolution. I can go freely in any direction

The modern word “highways” is derived from the way the Romans elevated their roads above the landscape, explains Ratledge. By building them up to a thickness of two to three feet, they were literally mounted “highways”. And although over the centuries the roads will have been ploughed away and might now only be a few inches high, Lidar is sensitive enough to detect those ridges.

When a colleague and friend developed software that transformed the Lidar data into a 3D model of the landscape, Ratledge was able to explore it virtually, seeking out the shadows cast by those ridges.

“It’s a little like Minecraft but in much higher resolution,” he explains. “I can go freely in any direction and because it’s my model I can put the sun in any direction I want and that’s critical. If you set the sun in the right directions – at right angles to the road – you can pick up these ridges. And if they all line up through multiple fields then you have an alignment. Once you’ve eliminated the possibility that the alignment belongs to the old railway or gas line then you know you’ve found a Roman road,” he says.

Ratledge’s personal holy grail had always been the missing road that must have once connected the major Roman towns of Ribchester and Lancaster.

“There was obviously a road between them but nobody could find it. For 45 years I’d been looking in the wrong place. But as soon as Lidar came out, I found it. When you find a road that’s been lost for a thousand years and you’re able to stand on it, you get such a tremendous buzz,” he says.

Before Ratledge’s recent work with Lidar, the northwest of England had been thought to be a relative backwater of little significance to the Romans, because of the dearth of their roads that had been found up to that point.

But it turns out that the Romans had their own “levelling up” agenda all along.

“When we found all the roads in the northwest and you look at the whole network through Cumbria and Lancashire to the Scottish border, it’s as good as you’d find almost anywhere,” says Ratledge.

Given that each road was eight metres wide, one metre thick, and must have taken two to three years to build, they were massive undertakings. For Ratledge this supports his contention that far from being a remote outpost on the distant edge of their empire, the region must have been of real strategic significance for the Romans.

Technology brings threats as well as opportunities for archaeology and heritage. There’s a risk that ready access to laser scanning can ‘deskill’ the process

Now that a dozen of Ratledge’s roads have been partially excavated, he has enormous respect for the Romans as engineers. Although some of the roads are now just a few scattered stones, other stretches are as good as new.

“There is this myth that they just drew a straight line and built on it. But no, their engineering is second to none. When you study them in detail you see that they were very clever. They reduced gradients and followed contours where they needed to. Although no maps survive, it’s obvious that their routes had been carefully surveyed from high points,” he says.

Ratledge shares his findings on a website called “Travelling With The Romans” and by uploading YouTube virtual walking tours where you can follow in their footsteps.

Given the speed with which technology has transitioned archaeology from a traditional field science to a citizen science accessible through a computer screen, there are some concerns about its future as an academic discipline.

It used to take an archaeologist years to fully map a newly discovered site, but now airborne survey techniques like Lidar can replicate that work in a few hours.

For Bob Johnston, professor of archaeology at Sheffield University, what has changed everything is the autonomy that the new generation of archaeologists has been granted, but he also raises concerns.

“Technology brings threats as well as opportunities for archaeology and heritage. There’s a risk that ready access to laser scanning can ‘deskill’ the process. Digital models, while they may look stunning, do not in themselves tell these stories – we still need to do the skilled, intellectual work of interpreting the evidence,” he says.

As a professor of archaeology at Oxford University, David Griffiths agrees that the technological revolution shouldn’t be allowed to signal the end of traditional fieldwork.

“Lidar is very good at showing you where complexity exists, but it doesn’t understand it for you,” he tells me. “Where a desk-based pixelated representation of reality exists, it is always best – if possible – to go out and experience the landscape. Both the technical visualisation side and the personal encounter with place and space are vital, and really one alone doesn’t cut it.”

Paradoxically, the real benefit of the new technology is its ability not only to discover sites but to preserve them too. In archaeology’s new golden age, the amount of material coming out of the ground will soon be greater than the museum space available to store it.

So sometimes the best way of preserving our past might be to leave it where we find it, undisturbed. Excavation without digging is very much the new trend in archaeology. Given the rapid advances in scanning technology, it will soon be possible to unwrap complex sites virtually, layer by layer.

When Parcak’s team started analysing satellite images almost 20 years ago, one of their most disturbing findings was the telltale “pockmarks” that reveal the extent to which a newly discovered site has already been pilfered by looters.

As an international criminal activity, only drugs and illegal arms trading surpass trafficking in stolen cultural artefacts. Interpol estimates the market in cultural property to be around $10bn (£8bn).

That just makes knowing where those sites of archaeological significance are all the more important, so that we can either protect them from looters or preserve them digitally before they’re erased by urban development.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments