Is Apple too big to fail? Let's hope so as failure would be catastrophic

In 2018 Apple became the first company to reach a market value in excess of $1 trillion. In the same year, the company's shares dropped 30 per cent. Josie Cox explains how it got there and where it's going next

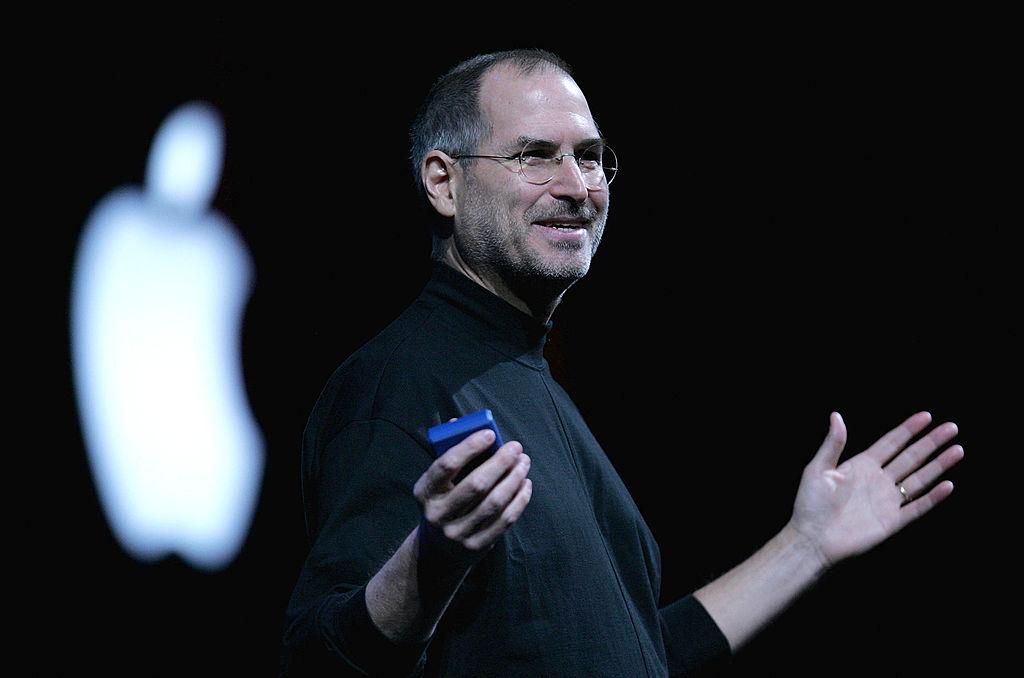

For an interview published in the Financial Times back in 2006, journalist Richard Waters hauled himself to a nondescript corner of the Californian city of San Jose to meet with a corpulent computer scientist called Steve. As Richard walked into a vinyl-clad diner called The Hickory Pit, Steve sat – bearded and burly – hunched over some sort of hand-held device, engrossed in a game of Tetris.

The setting of the interview was unusual for the FT. The salmon pink daily is more widely known for its profiles of the buffed and manicured business elite, lounging in grand villas, chalets and penthouse pads, preferably in Davos or Cannes. But Steve – eating cherry pie in a washed-out T-shirt – had certainly earned his column inches: 30 years earlier, together with another Steve and an electronics industry worker called Ronald, the Hickory Pit’s favourite tech geek created what would later become the world’s largest publicly traded company.

His unremarkable appearance and the profoundly mundane setting of his encounter with the FT, convey a banality neatly reflected in the origins of the very firm he was instrumental in founding: An experimental three-man band (the original start-up, if you will) that took a crazy punt on a simple motherboard and now has more cash than the vast majority of countries.

Growing the Apple

Apple was founded on 1 April 1976 by the late Steve Jobs, Steve Wozniak and Ronald Wayne in Cupertino. It wormed its way on to the tech scene with a creation named the Apple I, a computer designed and built by Tetris-loving Wozniak, and sold for the ominous sum of $666.66 – or about $2,900 in today’s inflation-adjusted money. Unremarkably, the name reportedly stems from Jobs’ fondness of the humble fruit.

Less than a year later, the company was incorporated. Wayne had already jumped ship, having sold his stake in the group for the paltry sum of $800, but – unhampered by the exit of a third of its staff – Apple’s operational revenues were heading north. According to media reports, they almost doubled every four months during the first five years of the company operating. Between September 1977 and the same month in 1980, sales increased by more than 500 per cent, on average annually.

The Apple II and Apple III followed, and the company’s success grew with every launch. On 12 December 12 1980 it listed on the stock exchange, publicly floating around 4.6 million shares at $22 apiece. The offering turned scores of Apple’s early employees into instant millionaires. Shares in the company ended the day at $29 each, giving Jobs a net worth of well over $200 million. He was 25 at the time.

In 1984, Apple launched the Macintosh. Its debut was marked with a high-budget neo-noir dystopian commercial, aired during that year’s Super Bowl and directed by Bladerunner’s Ridley Scott. The release was hailed a watershed moment not just for the tech world, but also for the advertising industry. Already then Apple was inventing itself as a generation-defining, industry straddling brand; a firm that challenged the status quo and confronted the norm ruthlessly.

Though Jobs and Wozniak both left the company in the mid-1980s amid disputes with management, predominantly over strategy, Apple’s success initially continued untarnished.

The price problem

In 1991 the company created the PowerBook, presenting a blueprint for all modern laptops. That same year it launched System 7, adding colour to the interface. But not all its products proved a hit. The company was struggling to tap into its client base and it was failing to gain traction with its strategy of marketing high-end products with a high price – dubbed the High-Right Policy – while simultaneously battling heavyweight rivals, like Microsoft, which in many cases were offering similar technology at a vastly smaller price.

By 1997, marred by constant leadership change, an unclear approach to the market and a series of painful restructuring exercises, Apple was forced to choose between sticking to its poorly performing guns or risking a dramatic high-stakes turnaround. It chose the latter. It snapped up NeXT, – Jobs’ new venture – for $429 million and scrapped the High-Right Policy. Shortly after, it launched the iMac G3, an affordable machine with a quirky, futuristic look that jarred with Apple’s previous designs, but spoke to a new generation of tech-savvy, progressive professionals. The move proved a lifeline for the financially bruised group and catapulted it into a new era. Apple computers were no longer just the tools of businessmen and accountants, but the product of choice for students, designers and artists. It had won over the creative elite and would continue to claim there support for many years to come.

Jobs, who had returned to Apple as an adviser in early 1997, assumed the position of interim CEO when Gilbert Frank Amelio, the company’s boss since February 1996, was pushed out for overseeing several quarters of lacklustre earnings. And it was at this time too that Jonathan Ive joined the upper echelons of management, injecting fresh energy into the brand and later designing the decade-defining iPod and iPad.

Beyond computers

The 2000s were a period of revival for Apple, which the company kicked off with a wild buying spree. It snapped up a portfolio of corporations, including a DVD authoring platform and a music software group. In May 2001, doors to its first retail stores opened and it debuted the iPod, of which more than 100 million were sold over the subsequent six years.

The iTunes Store launched in 2003. Within just two years it was the world’s largest music retailer. The MacPro, MacBook, and MacBook Pro hit the market with resounding success, marking the dawn of Apple’s gradual shift away from computers and towards the future of portable consumer electronics.

At the Macworld Expo on January 9 2007, Jobs announced the launch of the iPhone of which hundreds of thousands were sold within hours. A year later the App Store was introduced, allowing users to buy third-party applications for their devices and generating millions of dollars of revenue within its own right.

In 2010, shortly after Jobs took his first medical leave of absence, Apple introduced the iPad which was met with massive demand globally, helping the company’s market capitalisation eclipse that of arch rival Microsoft for the first time in over two decades. The iPhone 4 was released in June of that year, offering a range of new features, including video calling, and sporting a now iconic stainless steel design. The iPod Nano, iPod Touch and iPod Shuffle were also relaunched and the MacBook Air was updated, powering Apple to the top of the list of the world’s most valuable consumer brands.

In dire contrast to his professional success though, Jobs’ health was deteriorating. In January 2011 he announced to staff that he would be taking another period of leave of indefinite length, handing the reigns to chief operating officer Tim Cook. In August 2011 he officially resigned as CEO. He passed away in October in Palo Alto, succumbing to a rare and aggressive form of pancreatic cancer. Jobs was 56 years old.

After Jobs

In many ways, Apple’s post-Jobs years were an era of superlatives. Thanks largely to the launch of the iPhone4S and iPhone 5, and later the iPad mini, Apple’s market value in 2012 soared to an unprecedented $624bn, beating the previous record set by Microsoft. It used that financial momentum to further its quest to diversify into newfangled fields like augmented reality and artificial intelligence. It also remained fiercely committed to design and in 2013 recruited the former CEO of Yves Saint Laurent, as well as former Burberry executive Angela Ahrendts to oversee its digital strategy.

The company became a staple on lists of the world’s most valuable, best-known and influential brands. By January 2016 a billion Apple devices were reported to be in active use around the world. It moved into smart home technology and ride-sharing, through its investment in Chinese Uber rival Didi Chuxing. It bought Shazam, a music recognition service, launched its own video unit and signed a content partnership with Oprah Winfrey. Several series are reportedly in development as well as a film. Elsewhere collaborations with Hermes and Nike spurred sales of the Apple Watch, and in October 2018 it launched the twelfth generation of the iPhone. Its slogan? “Brilliant. In every way”.

In 2018, Apple became the first company in history to have a market value in excess of $1 trillion, an amount greater than the gross domestic product of most countries in the world, including Turkey

In late summer 2018, Apple became the first company in history to have a market value in excess of $1 trillion, an amount greater than the gross domestic product of most countries in the world, including Turkey, the Netherlands, Saudi Arabia and Sweden. Employment hit more than 90,000 and, according to some reports, the company has more readily deployable cash than the US Treasury. The combined wealth of the world’s 10 richest people – a list that includes Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, financier Warren Buffett, and Facebook founder Mark Zuckergerg – doesn’t even come close to the size of Apple’s market capitalisation.

Cracks appearing

The “too big to fail” economic theory prescribes that some organisations, particularly banks, are so large and influential, that their failure would be catastrophic for the broader economy. Apple is undoubtedly one of those organisations, and in the last few months of 2018 markets were offered a taste of what that could actually mean.

Shares peaked around the launch of the latest iPhone, and started trending lower shortly thereafter. Between early October and the end of the year, Apple’s shares lost more than 30 per cent of their value, taking them to below $160 from a peak of over $230 just a week earlier, and dragging swathes of the broader stock market with them.

Analysts said that investors were falling out of love with the name for a slew of reasons. Product sales were slowing and consumers were becoming more sensitive to prices amid fears of an impending economic downturn. After reporting a set of quarterly results on 1 November that reflected a weakening in crucial emerging markets, Apple’s shares fell by 7 per cent in a single day wiping an estimated $70 billion off the group’s value.

Executives at the time said that they would stop providing quarterly updates for the number of iPhones, iPads and Mac computers sold, unnerving investors further. The cost of new products also spawned worries, with the average selling price of iPhones climbing to $793 during the final quarter of 2018.

After reporting quarterly results that reflected a weakening in emerging markets, Apple’s shares fell by 7 per cent, wiping $70 billuon off the group’s value

“Our worry is there must be a limit to Apple’s pricing power,” George Salmon, an analyst at Hargreaves Lansdown, told Reuters at the time. “The group is now charging close to $800 per phone, and while that’s helping revenues climb despite flat sales volumes, one has to wonder how the strategy to shimmy up the price ladder fares in a downturn. If consumers start feeling the pinch, those price tags could put the punters off.”

Analyst Chaim Siegel at Elazar Advisors told the agency that trade issues between China and the US are also threatening to throw a spanner in the works if they make it hard for Apple to get the supplies it needs. “As for emerging markets slowing, that’s also contagion from China. Both trade war issues coming to reality,” he said.

Elsewhere analysts at Bank of America Merrill Lynch slashed their recommendation on the stock to “neutral” from “buy”, explaining that they are “incrementally concerned that not all the weakness is captured in the near-term” and that there are likely to be “further negative estimate revisions” to Apple’s financials. Analysts at Goldman Sachs cut their share price target on the stock repeatedly.

Others have shown concern about the company’s emphasis on its services business: ApplePay, Apple Music and the App store. Potential for growth is undoubtedly there, but the company has yet to share concrete plans about its strategy going forward and how it intends to keep growing.

Not helping the situation, Tim Cook in early January wrote a letter to shareholders in which he announced that Apple’s results for the quarter that ended on 29 December 2018 were likely to be worse than previously anticipated. Cook cited the unforeseen “magnitude” of the economic slowdown in markets such as China. The profit warning was Apple’s first since 2002 and dealt a fresh hefty blow to the share price, as well as the performance of dozens of smaller suppliers and competitors whose fate is closely linked to that of Apple. It also sent shockwaves through broader financial markets, sending stocks – which are generally considered a fairly risky asset – sharply lower in most regions and driving demand for perceived safe havens, like gold and Japan’s yen. The sell-off was a dramatic reminder of the sheer scale of the Apple ecosystem. If Apple sneezes many parts of the financial system will most certainly catch a cold.

Since then Apple shares have continued to trade sideways, keeping the company’s market capitalisation well below that psychologically significant $1 trillion mark and raising questions about how much more correcting still needs to be done, before – or if – the trajectory can turn.

The great unknown

So what will 2019 hold for the company which is no longer quite the world’s largest (having relinquished that role to Microsoft and Amazon)? Opinions are divided. While many experts who have been tracking the stock for years predict this to be a turning point, others consider it more of a blip.

“When we get into these situations where the current product may not be moving as well as investors expected, some get scared and then the fear compounds itself,” Jason Benowitz, a senior portfolio manager at Roosevelt Investors, told Bloomberg. “We’re not really too concerned. Some of this is probably just noise like it always is.”

Also speaking to the news agency, Ross Gerber, co-founder of Gerber Kawasaki Wealth & Investment Management, described the climate of fear around Apple as “absurd”. “It doesn’t make any sense. It’s a solid business even if it’s not going to grow as much as it did,” he said.

Apple is still hugely profitable. It’s sitting on well over $200 billion of cash, and shares – despite their recent brutal tumble – have roughly doubled in the past five years. The omnipresence of Apple devices across the planet also suggests that if the company’s heyday really is over, then its decline would likely be glacial rather than sudden. It simply has too many dependents, both in the corporate world and the consumer world, to swiftly fizzle out.

As for Wozniak, the smiley 68-year old with a penchant for pie and Tetris, is unperturbed; the ultimate bull, in market parlance. In an interview with CNBC at the end of last year, he said that Jobs would be proud of what Apple had become. Speaking of rivals, like Samsung, Wozniak said that they don’t present a real threat. They’re not innovating, he explained. They’re simply creating “fun features”. Apple, meanwhile, is concentrating on innovations that “literally affect everything we do all the time in life”.

If Wozniak is right, then Apple’s dominance is far from over. Technology famously knows no limits and it’s increasingly evident that consumer appetite hardly does either. We want lives that are interconnected, homes that are smarter than us, phones that manage our whole existence and privacy that is safeguarded unconditionally.

Amid all this, the most serious challenge for Apple will be to keep up with contracting attention spans. In a world of instant gratification, it’s becoming clear that he who fails to innovate is lost. Perhaps, just perhaps, that will prove Apple’s greatest obstacle yet.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments