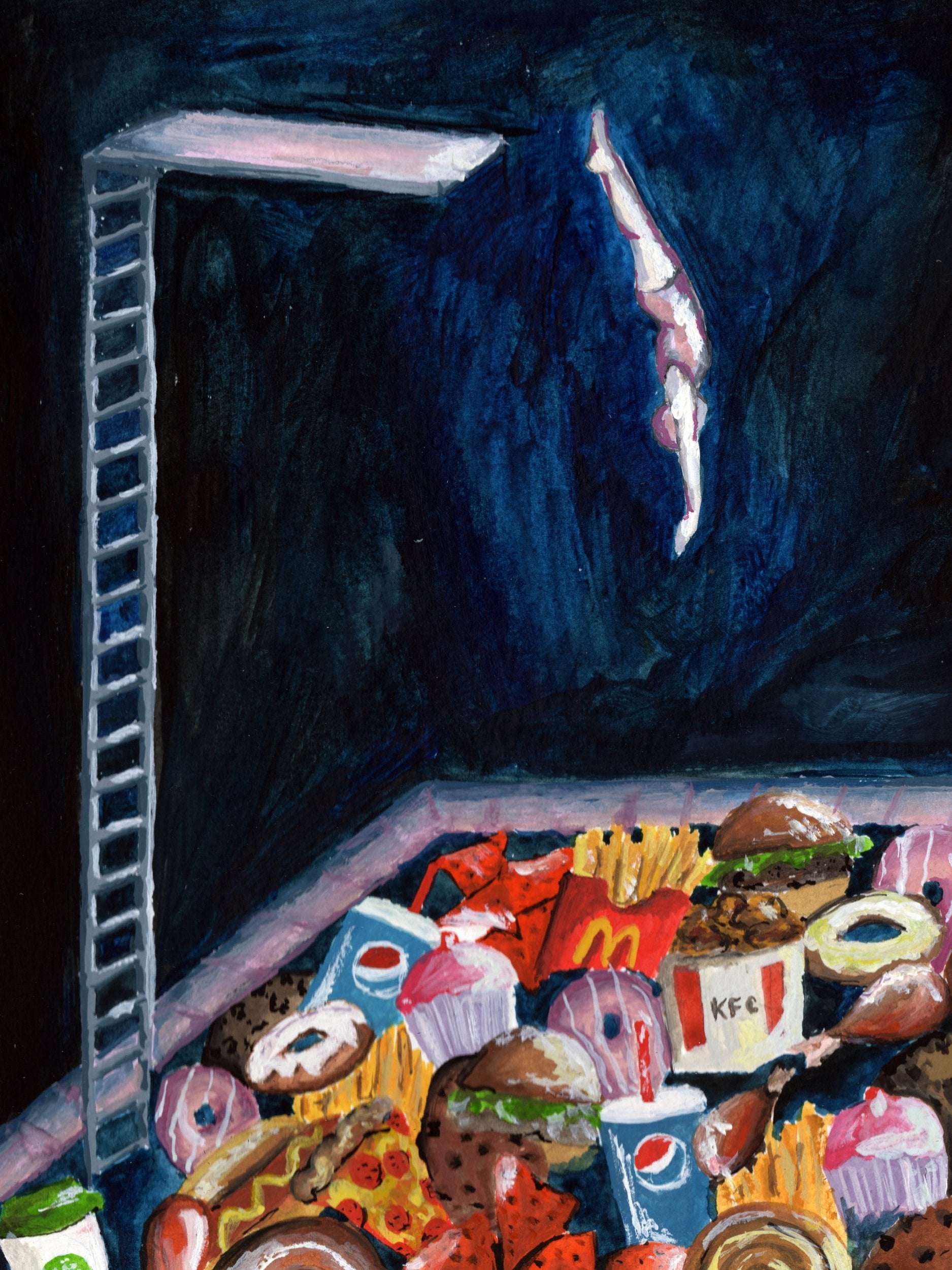

What will the end of the world look like? Will it be nuclear weapons or fast food that kills us?

Is everything getting better or is it really getting worse? Can it be both? Andy Martin talks to Martin Rees, the Astronomer Royal, about the shape of the future: what will it look like – and will there even be one?

Not with a bang but a whimper. TS Eliot’s bleak prediction of the way the world will end. John Cooper Clark cheekily tweaked it: Not with a bang but a Wimpy. Or more likely KFC or Burger King. We are capable of eating our way into extinction. If not through outright obesity then on account of the sheer mass of cows. Bovine emissions now outstrip cars, ships, trains and planes combined. Burgers are killing the planet a bite at a time. Just like “sleepwalking” into the First World War for lack of a sufficiently powerful attachment to peace, so too we have a lurking fondness for apocalypse. The End is Nigh is now a video game. Ask surfers: the spectacular “wipeout” is highly esteemed and respected, even if not exactly sought after. The worse the better.

A world-wide obesity epidemic could get messy. With any luck we will be saved (which is to say doomed) by a decent gamma ray burst from a neighbouring star going into meltdown. Which would vaporise us, tooth and nail. “At least we wouldn’t have to worry about Brexit then,” a Swedish friend said when we were discussing the chances. Of course, it may not happen for another billion years or so. By which time we will be negotiating for the Earth to leave the Milky Way and beef up trade with other galaxies.

There is a solidarity and egalitarianism to catastrophe that is lacking in all other scenarios. You don’t mind going up in a puff of smoke so long as everyone else is going with you

It is always possible that a hungry black hole – beloved of Stephen Hawking – could come along and gobble up the planet in a single gulp. But there is a more promising candidate in the shape of “strangelets”. Strangelets are simply highly compressed quarks (which were already fairly small to start off with). But there is a dark hypothesis to the effect that “a strangelet could, by contagion, convert anything it encountered into a new form of matter, transforming the entire Earth into a hyperdense sphere about a hundred metres across.”

I’m just trying to think how wide across I would be in those circumstances. The crash diet of all crash diets. I owe that particular vision to Professor Martin Rees, Astronomer Royal, and his new book, On the Future: Prospects for Humanity.

As he occasionally points out to people, he is not an astrologist and doesn’t have a crystal ball, but his book shrewdly and persuasively weighs up our chances of survival. Which, as we all know, is zero, once the sun conks out. As Maynard Keynes once said: “In the long run we’re all dead.” A strangely comforting thought. There is a solidarity and egalitarianism to catastrophe that is lacking in all other scenarios. You don’t mind going up in a puff of smoke so long as everyone else is going with you.

Maybe a rogue asteroid will smack into the planet and snooker us. But whether Bruce Willis is available to save the planet (as he did in Armageddon), it’s still not very likely. The “blaze of glory” narrative is always rather appealing, but to Martin Rees’s way of thinking, it’s a “dangerous delusion”.

Likewise, the Stephen Hawking vision of everyone taking off into outer space (Hawking was in the same graduate research group in applied mathematics as Rees, but two years ahead). “Terraforming Mars is always going to be a lot harder than fixing our own climate. Nowhere in the solar system is half as congenial as the coldest place on this planet.” And most likely it would only be Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, Richard Branson and assorted billionaire adventurers in the rocket anyway.

“Just don’t mention the strangelets!” he said, when I went to speak to Rees in his rooms in Trinity College Cambridge, where Isaac Newton once studied and where Rees was Master not so long ago. So I apologise for mentioning them. But how could I not? The problem with strangelets is that once they worm their way in you end up talking about nothing else (and whole websites spring up dedicated to them).

With his great mane of silver hair Rees puts me in mind of (harking back to the previous century) the philosopher Bertrand Russell, able and willing to give an opinion on anything under (or, indeed, over) the sun. He is pro-euthanasia, but says he wouldn’t mind immortality, just so long as he can remain on Earth and not have to float off into some celestial holiday camp where you lie around the pool all day. “Suppose you were a Roman who was still alive today – you wouldn’t be bored.”

It has to be admitted that the future is not what it used to be. Back in the day, let’s say in the heyday of Dan Dare, “Pilot of the Future”, everyone was going to have a personal jet-pack à la James Bond. Or possibly some kind of helicopter rotor attached to their heads. And if we weren’t flying through the air then we’d be living in vast cities under the ocean. Or maybe on artificial satellites orbiting the Earth. All doors would slide open noiselessly at the touch of a button. Everything would work like magic. That was the theory. It was a naive form of technological optimism. Everything is going to get better. And maybe we’ll learn to behave better too (as Stephen Pinker maintains in The Better Angels of Our Nature).

We’ve always had the Frankenstein anxiety, on the other hand. Even setting aside actual nuclear weapons – and the realistic potential for techno-annihilation set out in the recently published Accessory to War: the Unspoken Alliance between Astrophysics and the Military, by Neil deGrasse Tyson and Avis Lang – we suspect that everything we invent is going to kill us, one way or another.

Even setting aside actual nuclear weapons, we suspect that everything we invent is going to kill us, one way or another

Socrates was fairly dubious about this new-fangled technology called “writing”. We probably feel somewhat similar about the internet. Hal, the super-computer of 2001, A Space Odyssey fame, comes to the conclusion that it would be logical to get rid of humans, because they’re bound to screw up the mission. And he surely had a point. Arnold Schwarzenegger, as the original Terminator, shared this view, and yet we elected him Governor of California.

Looking on the bright side of life, my personal favourite among utopian thinkers is the French visionary Charles Fourier, who dreamed up the “Phalanstery” and, shortly after the French Revolution, foresaw a world in which the oceans would be turned to lemonade (I’m not sure what the fish would make of that though). In the Age of Harmony (some distance in the future even he allowed), there would be so much to eat and drink that we would have to stage culinary Olympics in which gold medallists would be serenaded by the sound of a thousand champagne corks popping. And – a first in human history – everyone would be sexually satisfied too (with an AA call-out service for anyone feeling a bit desperate). Sadly, Freud had to go and point out that that would mean an end to civilisation as we know it, since all creativity depends on “sublimation” ie frustration dressed up to sound more sublime than it feels.

So is everything getting better or is it really getting worse? The fact is we are now living in a quantum world where both of these propositions are true. The classic quantum thought experiment revolves around a cat (Schrödinger’s) whose fate is determined by the indeterminate, indifferent behaviour of a random particle. Is the cat alive or dead? Both alive and dead, comes the paradoxical answer. In the same way our futures are now “superposed” and simultaneous. We are living on a zombie planet that is both alive and, increasingly, dead, or at least in a death-spiral.

We now have parallel universes in which some select parts of the population (I should add, of one species) live in pampered bubbles cut off from reality while everybody else is going under. With corresponding effects on migration. And a sense of bitterness and resentment. This asymmetry partly accounts for why the eschatological vision of “end times” is so appealing, because at least it levels the playing field and solves all existing problems (even if it creates new ones: Yes, you believers this way; unbelievers over here, please.)

Martin Rees points out that our social and subjective estimation of disaster has evolved over the ages, so that, in effect, everyone is much more of a snowflake than we ever used to be. “Back in the Middle Ages, the Black Death wiped out as much as half the population in Europe. But people carried on because there was not a lot they could do about it. Now, in the event of a pandemic, if only 1 per cent of the population were to die, the whole health service and the political system would collapse.”

On one hand, we are faced with truly global phenomena, going far beyond borders, on the other, in our fear and anxiety, we are retreating behind our picket fences, as if that could save us from an impending tsunami. A quantum world driven by a quantum mentality.

I assume the existence of aliens. If you can have life flourishing in the volcanic vents at the bottom of the deepest ocean, there must be scope for life in the vicinity of the (approximately) 1022 stars in the known universe. The only question is are they going to be more like the Mekon, Daleks and Alien, or cuter, like ET? Or giant jellyfish? I think I’d really be scared if they turned out to resemble the most ruthless, vicious, vindictive, and murderous species we’ve come across so far, ie humans.

We are relying on a star in the Vega system, or a visiting asteroid, or aliens landing on Earth, or the Second Coming, or faster-than-light starships, or plain old death and transcendence, to resolve all our issues, and come up with the final fix

“The prospect of an end to the human story would sadden those of us now living.” So says Martin Rees in his book. But he is sometimes almost too rational. Perhaps even stranger than strangelets is that we are succumbing to a prematurely terminal way of thinking. In our mythic, symbolic way of thinking, we are relying on a star in the Vega system, or a visiting asteroid, or aliens landing on Earth, or the Second Coming, or faster-than-light starships, or plain old death and transcendence, to resolve all our issues, and come up with the final fix.

There is a brilliant short story by Arthur C Clarke in which a couple of computer engineers mock the belief of a group of Tibetan monks who reckon that the point of existence is to utter “the nine billion names of God”, after which the universe will simply cease to exist. But at the end of the story, as they are crossing a high Himalayan pass, they look up into the night sky (for the last time) and notice that “overhead, without any fuss, the stars were going out.”

It’s beautiful and elegiac, but we need to get out of the cosmic graveyard. Every time we write “THE END” we can’t help thinking of how, one day, it will all be over. We can’t wait to get to the end. Maybe, like Martin Rees, we need to think more in terms of staying alive a lot longer. The Earth has been around for a few billion years and, strangelets and Tibetan monks notwithstanding, will almost certainly stick around for a few more. Rumours of its demise have been greatly exaggerated. It’s not apocalypse now. It’s more carry on, but don’t necessarily keep calm. If you really want a future.

Andy Martin is the author of Reacher Said Nothing: Lee Child and the Making of Make Me. He teaches at the University of Cambridge.

On the Future: Prospects for Humanity, by Martin Rees, is published by Princeton University Press.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments