Bringing a Dutch master home – what makes Vermeer so remarkable?

An exhibition at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam brings together more of his paintings than ever before, writes William Cook. It shows just how brilliant an artist he was

In the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, one of the world’s great art galleries, art lovers from all around the world are flocking to the biggest exhibition of the year. The Rijksmuseum’s new Vermeer show has received a slew of five-star reviews, laden with superlatives. Does it deserve such lavish praise?

Wandering around this exhibition, wide-eyed, my own review is just three words long: believe the hype. Vermeer really was that special, and this show really is that good. But what makes him so remarkable? What sets him apart from other artists? And why is he so revered?

“I think it starts with his ability to observe,” says Pieter Roelofs, head of paintings and sculpture at the Rijksmuseum, as we stand before these timeless masterpieces that are so powerful yet so subtle and discreet. “There is no other artist in the 17th century, in the Netherlands, who is able to observe as he did.” He’s quite right, of course – but that’s really only the half of it.

Never mind the Netherlands – never mind the 17th century. I can’t think of any artist of any era, anywhere in the world, with such acute powers of observation. Vermeer didn’t just record the details of the world around him: he explored the psychology of his subjects. He expressed how it feels to be alive.

“If you close your eyes and you think of a moment of intense happiness, at that moment everything kind of comes together – it seems as if time stands still,” says Taco Dibbits, the Rijksmuseum’s director. “That’s exactly what Vermeer’s paintings radiate. I think that’s why, nowadays, when there’s so much happening in the world, we long for those moments.” I know exactly what he means. Each painting is an oasis, a refuge from the hurly-burly of modern life. “They remind you of those moments where everything is just right.”

“The way he paints, it’s so intimate,” concurs Ige Verslype, a conservator at the Rijksmuseum. “That’s what makes it so moving.” As you observe the women in his paintings – reading letters, writing letters, staring out of windows, lost in thought – you feel as though you’re eavesdropping on an intensely private, emotive scene. Vermeer cares about his subjects. This wasn’t just a job.

Part of what makes Vermeer so exceptional is the sheer scarcity of his work. He only produced a few dozen paintings, over the course of 20 years. Even allowing for his relatively short career, and his relatively early death (aged 43), this was an extremely modest output. No other great artist left behind such a small body of work. Yet within that compact corpus lies incredible variety. “He keeps experimenting, he keeps trying to do new things,” explains Verslype. “You have such a small oeuvre, and you have so many different styles.”

Estimates vary about the exact number of pictures Vermeer painted. Most experts put it at around 50, although a lot of that is guesswork. The tally of surviving paintings currently stands at 37, though the authenticity of several of these has been contested (only a few of his paintings are signed, and most of them are undated). There are archival records of several more, probably destroyed in wars or fires – the rest is pure conjecture. Of those 37 survivors, 28 have been brought here to Amsterdam: an unprecedented feat.

The Rijksmuseum has rounded up Vermeers from half a dozen countries – Britain, Ireland, France, Germany, Japan and the USA. Logistically, this is a great achievement, but it’s a diplomatic triumph, too.

These paintings are several hundred years old, they’re extremely fragile, and museums are loath to lend them – partly for fear of damage, and partly for fear of forsaking their star attractions. This is the first major Vermeer retrospective in almost 30 years. The National Gallery of Art show in Washington DC, in 1995, which subsequently travelled to the Netherlands, gathered together 21 Vermeers. For once, it’s not hyperbole to call this a once-in-a-lifetime event.

The nine omissions include several paintings that aren’t allowed to travel, either because of their fragility or because the conditions of their bequests forbid it. The Concert was stolen from Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in 1990 and is still missing. It’s a shame not to see The Astronomer (currently at the Louvre in Abu Dhabi) alongside its natural twin, The Geographer (which has travelled here from Frankfurt). The Art of Painting, arguably Vermeer’s greatest masterpiece, is also conspicuous by its absence – it’s still in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. Oh well, never mind. Twenty-eight Vermeers is enough to be getting on with – a feast for lovers of fine art.

In an exhibition devoted to any other artist, 28 works would feel like a small show. For Vermeer, it feels vast. That’s not only because seeing so many of his works together is such a rare treat; it’s because each painting is so complex. They’re supremely satisfying, yet emotionally draining. After two hours with them I felt exhausted, yet it wasn’t nearly enough. The best way to see them would be to pay 28 separate visits and view them one at a time.

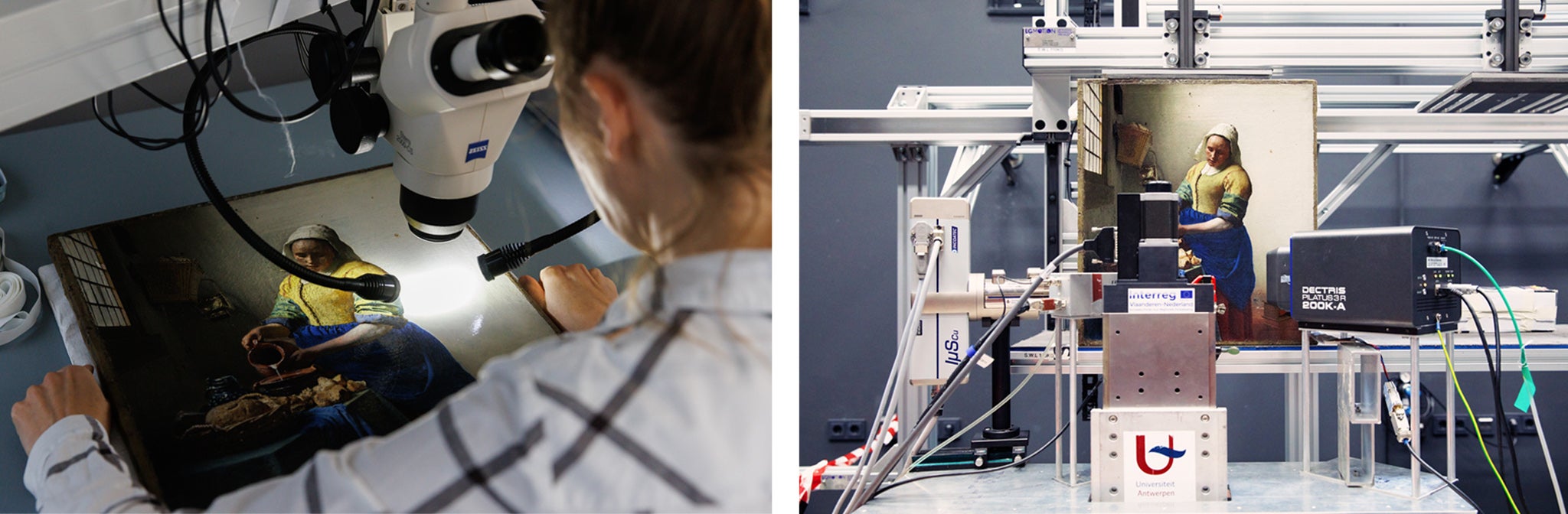

That complexity is a surprise because, superficially, Vermeer’s pictures seem so simple. Unlike other artists of his era, he strips away every superfluous element – X-rays of his pictures reveal extraneous details that he sketched in and then painted out. That’s what makes his paintings so striking, as iconic as classic album covers: The Milkmaid; The Love Letter; Girl with a Pearl Earring.

Yet these clear and lucid images are full of psychological insight, what the art historian Maurizia Tazartes calls “the poetry of silence”.

An even greater asset is Vermeer’s extraordinary naturalism. David Hockney, among others, has suggested he may have used a camera obscura – an early type of camera that projected a photographic image onto a wall. This would account for his mastery of perspective, and his photographic sense of focus and composition – pixellating foregrounds, blurring backgrounds, cropping out the edges of every frame. His brushstrokes are almost invisible. His pictures are candid snapshots, more like Polaroids than paintings.

However, Vermeer’s greatest talent was his unique mastery of light. He was the first artist to understand that warm light casts a cold shadow, and vice versa – that yellow light sheds a blue shadow, and the other way round. This depiction of light through colour really puts you in the room, making you an active participant in his paintings rather than a passive spectator. Each painting is a hidden window on another world. Paintings of similar scenes by other artists seem staged and theatrical – Vermeer is more like a cinematographer. Is that why his art still speaks to us, in our cinematic, televisual age?

Another thing that makes Vermeer so alluring is that we know so little about him. He left no letters or diaries. He painted no self-portraits. Yet far from inhibiting our interest, this sense of mystery only adds to his appeal.

Lately, historians have uncovered a lot of new information about his life and times, and this patient research has been brought together in a new exhibition called Vermeer’s Delft, housed in the Prinsenhof, a historic palace in the artist’s hometown. This colourful survey paints an evocative picture of the world he inhabited, and provides a vivid backdrop to his elusive biography.

“In Delft, we bring people closer to the man behind the myth,” says Janelle Moerman, director of the Prinsenhof, at the opening of this exhibition. “Here we try to present the whole puzzle – how the city as a whole inspired Vermeer,” adds her colleague Hester Scholvinck, head of collections and presentations. “Seeing his paintings and then seeing this exhibition, I hope the visitor will then recognise where he comes from.” They will indeed.

Johannes Vermeer was born in Delft in 1632. His father was an innkeeper who dabbled as an art dealer – a jack of all trades, neither rich nor poor. Johannes probably received a reasonably good education, possibly at the local grammar school, though there’s no record of him going to university. Indeed, for the first 20 years of his life, there’s no surviving record of him doing anything at all. He must have been apprenticed to an established artist, since this was an obligatory requirement for membership of the local artists’ guild (a sort of trade union) of which he subsequently became a member. Yet where he trained, in Delft or elsewhere, and under whom, remains a riddle.

When his father died in 1652, Vermeer inherited his inn, and in 1653 he married Catharina Bolnes, who went on to bear him 15 children. This marriage was a double-edged sword.

Catharina was relatively wealthy. She was also a Catholic. Vermeer, like most Dutchmen, was a Protestant. Her money brought him closer to high society, while her religion set him apart. Whether he actually converted to Catholicism remains unclear, but either way, marrying a Catholic must have distanced him from the establishment. Although the Netherlands was a relatively tolerant country by 17th-century standards, Catholics were still barred from top jobs, and had to worship behind closed doors.

Delft was a lot smaller than Amsterdam, but it was no backwater. “It was a very lively town,” says David de Haan, curator of Vermeer’s Delft. “Delft really was the artistic hotspot of the Dutch Republic.” A family business and a wealthy wife enabled Vermeer to paint to please himself rather than pandering to the art market. He didn’t have to paint sycophantic portraits to pay the bills. He could spend longer on his paintings, rather than rushing to meet deadlines. His genre paintings are sincere and heartfelt, mercifully free of the clumsy humour so common in similar pictures by his peers.

To modern eyes, Vermeer’s pictures seem so different from those of his contemporaries that you might assume he was either a great success or a total failure. Strangely, it seems that he was neither. He didn’t move up or down the property ladder; his house was respectable but unspectacular. Some collectors praised his work; others complained that it was too expensive.

If the Netherlands had remained at peace, Vermeer might have lived to a ripe old age and painted many more paintings – Rembrandt, his only equal, outlived him by 20 years – but in 1672 the French invaded and the local economy collapsed. This calamity spelt disaster for Vermeer. From then on, he produced hardly any paintings, and it seems he sold none at all. In 1675, he died suddenly – probably of a heart attack, possibly of a broken heart.

“Owing to the great burden of his children, having no means of his own,” recalled Catharina, “he lapsed into such decay and decadence, as if he had fallen into a frenzy, going from health to death within a day and a half.”

Vermeer left no assets, apart from a few unsold paintings. Catharina had to give two of them to the local baker in order to settle the family’s bread bill (Woman Writing a Letter with Her Maid, now in the National Gallery of Ireland in Dublin, and The Guitar Player, now in Kenwood House in London). With a large family to feed, she was forced to file for bankruptcy. By the time she died in 1687, aged 56, her husband’s work was already long forgotten.

During the 18th century, Vermeer virtually vanished from art history. When his paintings cropped up on the open market, they were often misattributed to other artists – perhaps accidentally, or perhaps deliberately in order to attract higher prices. The revival only began in 1866, nearly 200 years after his death, when a French art critic called Theophile Thore wrote a series of effusive articles praising this unknown artist, dubbing him “the Sphinx of Delft”.

Thore set the ball rolling, and during the late 19th century the Vermeer renaissance gathered pace. Van Gogh loved his use of colour. Monet and Renoir were both fans. After centuries of obscurity, popular taste had finally caught up with him. Today, he’s more popular than ever – the inspiration for novels and movies; an artist for the Instagram and TikTok generation.

And although we still know little about him, his ghost still haunts the streets of Delft, where he spent his entire life. The house where he lived and the house where he was born are both long gone, but the church where he was baptised and the church where he was buried are both still there, and the surrounding streets are still much the same. He’d still recognise the main landmarks – he could still find his way around. You can walk out to the spot where he painted his View of Delft (“the world’s most beautiful painting” according to Marcel Proust). The vista is remarkably unchanged.

And even though his paintings were confined to a few streets within this compact city, today Vermeer’s appeal is worldwide. “If you bring Vermeer to Japan, you get the same kind of reaction as when you bring him to Brazil, or Canada, or Qatar,” says Roelofs. “There is something universal in his paintings that we can easily relate to.” How wonderful that such introverted pictures, depicting such everyday activities, still retain the power to reach out across the centuries and excite art lovers all around the globe.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments