Amritsar centenary: Should Britain apologise for its colonial atrocities?

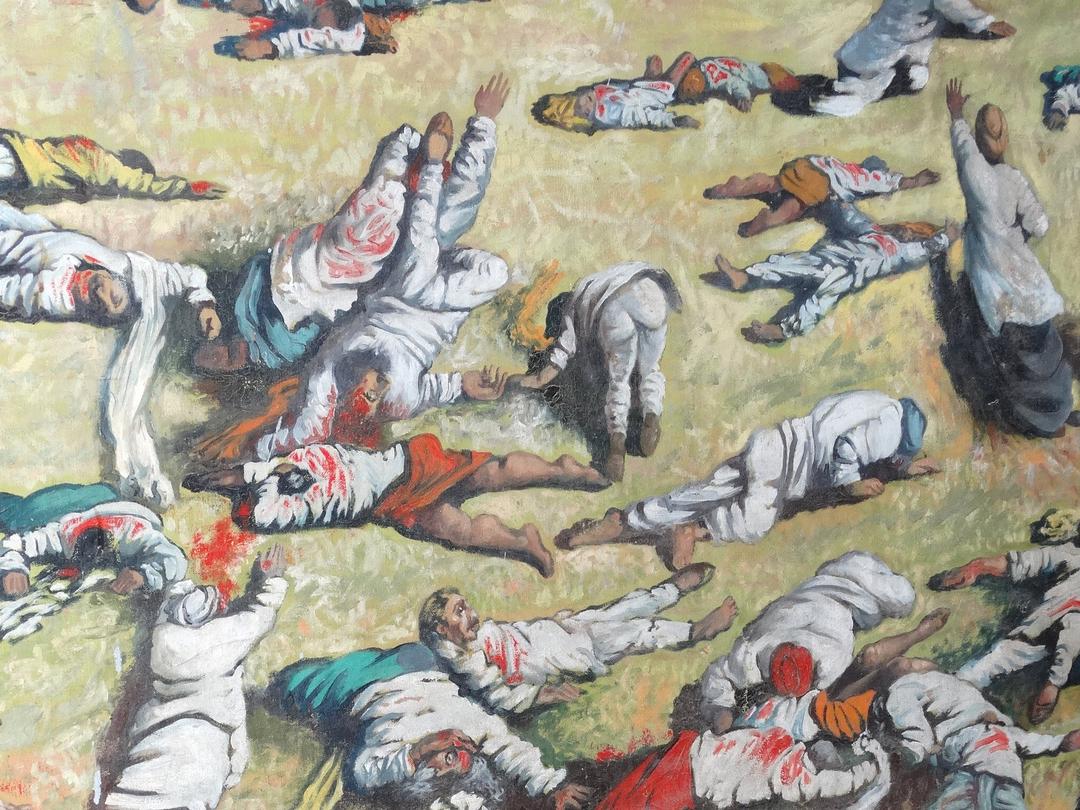

The massacre at Jallianwala Bagh saw more than 500 unarmed Indian men, women and children killed by British army riflemen. One hundred years on, families say the wounds still have not healed. Adam Withnall reports from Amritsar

The walled garden at Jallianwala Bagh in Amritsar is unrecognisable today from the spring of 1919, when it became the scene of the single bloodiest act of violent oppression in Britain’s colonial occupation. On 13 April India will mark the 100th anniversary of the massacre of hundreds of unarmed men, women and children by British soldiers who had been sent to quash what was believed to be a mounting rebellion.

Many myths and misconceptions now surround the events that unfolded in April 1919, but the sheer scale of the brutality involved has seen the Jallianwala Bagh massacre become infamous in India as an essential landmark on the country’s path to independence.

Pressure has mounted in recent months on the current British government to take the centenary as an opportunity to issue an historic apology. For the families of those killed, who say they have been suffering the consequences of the massacre for 100 years, it could finally offer some closure. It is impossible to say precisely how many people were killed in the garden on 13 April 1919. The official British toll from the time was 379, but a new, definitive count by Amritsar’s Partition Museum has come up with 501 named victims, plus an indeterminate number whose names may never be known.

Between 10,000 and 20,000 people had gathered in the park to attend a political meeting staged by local leaders, angry at a recent crackdown on dissent by British officials, for whom Amritsar was a key administrative centre. Three days earlier, on 10 April, riots had broken out across the city during which five Europeans were killed and an influential British schoolteacher was assaulted in the street. Control of the city was handed over to the army and General Reginald Dyer was tasked with enforcing a ban on public assembly.

When the meeting in Jallianwala Bagh was called the night before, organisers knew they might face trouble, and some told their wives to stay at home.

Nonetheless, at 4pm on 13 April the crowd included “a lot of people who didn’t know exactly what the meeting was, so weren’t necessarily politically involved”, says Dr Kim Wagner, a senior lecturer in British Imperial History at Queen Mary University London and author of Amritsar 1919: An Empire of Fear and the Making of a Massacre. “There were also children playing in the picnic area and there were pilgrims who happened to be in that space, which is right next to the Golden Temple,” he adds, referring to Amritsar’s most famous landmark for Sikh devotees.

It was then that the general and his soldiers walked into the garden armed with rifles. At a later inquiry, Dyer said he would have brought in a machine gun too if it had fit in through the narrow gates.

If Britain apologised and extended its welcome to the families, which have been suffering for 100 years, that would start to make for better relations

Just 30 seconds elapsed from the army’s arrival to the first rounds being fired. The guns did not fall silent for more than 10 minutes, after which 1,650 rounds had been shot and, in addition to those killed, more than 1,500 people were wounded.

Sunil Kapoor, 42, describes this as the moment that changed his family forever. Sitting in his home in the cramped streets of downtown Amritsar, he proudly displays a portrait of his great-grandfather Lala Wasoo Mal, one of the organisers of the Jallianwala Bagh meeting and one of the first victims whose identity was confirmed by the British at the time.

Kapoor’s ancestor was then aged 45 and a successful merchant, making him an influential figure in the community. He was at a smaller gathering on 12 April that preceded the Jallianwala Bagh event and helped raise 1,200 rupees – a large figure at the time – for the political cause.

At around 7pm, when Mal did not return home from the park, his six-months-pregnant wife Puram went to try and find him, Kapoor says. “She was only 21 at the time. She arrived at the scene to see blood and bodies everywhere, everyone was screaming. It took her more than one hour just to find her husband.”

Mal was gravely hurt, after receiving two gunshot wounds to the chest. Puram stayed by his side through the night until Rotary Club volunteers took him to hospital in the morning but, with no doctors or nurses available and no hope of emergency surgery, he died six days later. Puram was too young to take on her husband’s businesses so they had to close, and she was forced to live off the family’s savings while raising Kapoor’s grandfather.

“The massacre changed her,” he says. “She had to become an iron lady, to be strong for her son. And she became inspired afterwards to work for the end of British rule. It was her tribute to my great-grandfather.”

Puram gave evidence at the Hunter Commission, a British inquiry into the shooting that criticised some aspects of the massacre but which was overall considered a whitewash. Kapoor says she appeared at the inquiry in Lahore and told Dyer to his face that he “must pay for the sins of what he has done”. Dyer, who had not learned the local language, did not understand, Kapoor says.

Kapoor met David Cameron when the then-prime minister visited Amritsar in 2013 and expressed “deep regret” for the massacre. He speaks positively of how though Cameron “could not openly apologise, his body language showed how he felt it in his soul”.

Kapoor, who also heads a small foundation for the families of those killed at Jallianwala Bagh, says the centenary is a “good time” for Britain to finally deliver a full apology. And in lieu of compensation for the families, he would like to see them invited to address the British parliament in order to tell their stories and receive some form of honour on behalf of their ancestors.

“If Britain apologised and extended its welcome to the families, which have been suffering for 100 years, that would start to make for better relations,” he says. Jaswinder Singh, a tour guide who has been working at what is now the Jallianwala Bagh Memorial for nine years, stands at the spot from which the soldiers had surveyed the crowd and then started shooting.

People were here for a protest. General Dyer came here with soldiers, waited for people to gather and then ordered the soldiers to fire. Many people died. The sacrifice they made here gave a spark to the minds of Indians who wanted independence

He says many of those he shows round are amazed there hasn’t already been an apology. “I have many European clients, a lot of them British. When I bring citizens of the UK here they feel so sorry, sometimes they start crying,” he says.

Britain’s official stance, reiterated in a House of Lords debate in February and by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office this week, is that the government at the time condemned the massacre and that the matter has been dealt with. “Visitors expect that it must already have happened,” Singh says. “They feel that if just saying sorry can help heal the wounds here then why not just do it.” He says that if an apology were to be issued, “it would mean a lot for the whole nation”.

The park was some five feet lower in 1919, and the soldiers stood on an embankment as they started firing. Now, the whole site has been raised to a uniform level, with a 1960s-installed obelisk dominating the view. Tourists walk the hedge-lined paths among ornate flower beds and crude topiary figures of riflemen, shading under large red stone structures none of which existed at the time of the shooting.

Families with selfie sticks pose for photographs next to the gaudy, pink-roofed “Martyrs’ Well”, from which legend has it 120 bodies were pulled after the massacre ended. There is no historical evidence to support this claim, but it is still repeated on a placard in four languages.

The most historically significant points in the park are three walls where the brickwork is still pocked by bullet marks from the British rifles. Though highlighted by white boxes, these too have deteriorated to become almost indistinguishable, worn down by curious fingers tracing the path of the bullets. A glass barrier keeping tourists at a distance was installed a couple of years ago.

“People don’t always value this place,” bemoans Singh. “For some it is a serious place but for many it is just another tourist spot. They just come here to take selfies.”

Efforts are being made to spruce up the site which, on the day of the centenary itself, will host a special event featuring the vice-president of India. Visitor numbers are also up, with tourists from across the country thronging through the small front gate. Vishwas Sini, 22, is visiting with his cousin from Haryana. Even before touring the site, he is aware of the basic history after studying the massacre at school – he, like many here, repeats the story of the “many bodies pulled from the well”.

“People were here for a protest,” he says. “Gen Dyer came here with soldiers, waited for people to gather and then ordered [the soldiers] to fire. Many people died. The sacrifice they made here gave a spark to the minds of Indians who wanted independence.”

Naresh Parikh, 72, is visiting with his family from Gujarat. “This was a terrible act that happened here,” he says. “The British general stood here and killed thousands of people.”

Gurjeet Singh, 18, is a relatively local tourist from within Punjab state. Nonetheless, he admits he knows “very little” about the incident. “Gen Dyer killed around 100 people and some people died in the well. That’s all I know,” he says. Their comments, and those of others like them, display what Wagner describes as the most persistent myth surrounding the massacre, that it was all the act of one man – the “bad apple narrative”, as he calls it, exonerating the wider system of which Gen Dyer was a part.

“In the House of Lords debate, peers kept returning to a quote by [war minister] Winston Churchill from the time, calling the massacre ‘a monstrous event which stands in singular and sinister isolation’,” Wagner says. “But he denounced it in order for the empire, for Britain, not to take responsibility. This is why people are so invested in figures like Churchill and Dyer – it is not about the facts, it is essentially explaining away the violence.

“If you do not accept that General Dyer was a one-off – and the same pernicious logic was displayed by countless other officers over the course of the empire’s history – then it rocks the entire system upon which the British rule operated.”

If the park today has its shortcomings from the perspective of historical accuracy, efforts have been made to rectify the situation in the lead-up to the centenary.

A special exhibition has been curated at the nearby Partition Museum in the city, which provides a timeline showing how the riots in the days leading up to 13 April 1919 set the stage for the massacre and, perhaps most crucially, how the bloodshed was followed by an even more restrictive period of martial law.

These martial law orders, given by Gen Dyer himself, banned activities including riding a bicycle and walking down the street in groups of four or more. Those who breached the orders were stripped naked and publicly flogged.

The exhibition highlights newspaper clippings from the time, including the first bulletin about the massacre that ran in Britain’s Civil and Military Gazette on the 16 April as follows: “As the crowd refused to go the order to fire was given. There were heavy casualties amongst the mob, several hundreds being killed and injured, and there was no further trouble.

Instead of shying away from it, the British government should make clear that this is not the same Britain as it was 100 years ago. There is a deep, festering wound here. It is worth putting some closure on it

More importantly, the exhibition defines the Jallianwala Bagh massacre as “not an isolated event but part of a larger system of colonial oppression”.

Kishwar Desai, the museum’s chair, said that the work to produce the exhibition had inspired her to write a book on the massacre last year. She said the digital materials were being shared for exhibits in Manchester, Birmingham and London as part of events around the centenary.

“This was a turning point in our history,” she says. “Even Gandhi himself, who was a fan of the British up to that point – once the truth began to come out about what happened that day and in the aftermath, it became very difficult for him to continue to believe in the fairness of the British.”

She says it could be considered the single worst atrocity of the Raj. “The more I researched the accounts of it, the more heartbroken I became,” she says. “These were people who had fought the war for the British, who had died for the British. And even after the massacre they are not given medical help, they are called rabid. How could they be so cruel?”

Desai says that, other than the centenary itself, there “can be no other moment” for an apology after so many years. “I feel an apology is important – it is not for us. It is for those who died,” she says. “For me their spirit is still alive, and it is their spirit that has carried us through to where we are today.

“Instead of shying away from it, they should make clear that this is not the same Britain as it was 100 years ago. There is a deep, festering wound here. It is worth putting some closure on it.”

British government officials were due to address the centenary this week during debates at Westminster Hall and at prime minister’s questions, but British representatives are not expected to attend any of the key anniversary events planned for Saturday. Speaking during the Westminster Hall debate on Tuesday, Foreign Office minister Mark Field said he had been to India three times in the past 18 months and that he had listened to the ”very, very compelling” speeches in favour of an apology.

Nonetheless, he said that it was ”not appropriate for me today to make the apology that I know many would wish to come”, going on to say that the government had concerns about the “financial implications” of apologising. While the government had previously raised hopes by suggesting it was “reflecting” on the matter of an apology, it is now thought unlikely that any statements will deviate far from the UK’s previous official stances.

Field said Britain’s envoy to India would at some point travel to lay a wreath at the Jallianwala Bagh memorial. “It is right that we mark the centenary of this tragic event in Amritsar in the most appropriate way and that we never forget what happened,” he said. “It was a shameful episode in our history and one that we deeply regret to this day.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments