The Amazon effect: How independent booksellers are fighting back

As the online giant reaches its 25th birthday on 5 July, James Moore finds out how the small brick-and-mortar sellers have managed to compete in the face of plummeting prices on the internet

Could they even make Notting Hill today? This was the question one of my editors asked with the approach of Amazon’s 25th birthday. For those unfamiliar with the movie, which is not to everyone’s taste, it’s a Bafta-winning romcom centred on a chance encounter between a Hollywood star, played by Julia Roberts, and Hugh Grant’s independent bookseller, whose fictional shop is located in the fashionable west London locale.

The question was raised because of the impact the rise of Amazon has had on high street bookshops. It has been huge and could be categorised as catastrophic, disastrous, or devastating. Take your pick. Figures from the Booksellers Association show that the UK and Ireland have lost more than 1,000 independent bookshops since 1995, in excess of half of the BA’s membership.

Several chains have also gone. Borders is perhaps the most high-profile example of an Amazon-related failure, but a number of smaller and regionally based outfits have disappeared too. They include Sussex Stationers, James Thin and Bookland, all of which were once fixtures on the high streets of the regions in which they operated; pleasant places to go and browse awhile. Yet the 2018 figures brought a ray of light for the embattled sector. They show an increase of 15 shops over the 868 recorded in 2017, one shop above the nadir of 867 recorded in the previous year.

Ron Johns is one of the survivors. The proprietor Mabecron Books has four shops in the west country. A passionate and opinionated bookseller of considerable skill, the word he chooses for the impact of Amazon on his trade is “devastating”.

“They have the wealth of a small country and the ability to dictate what they want to publishers and suppliers. They have used this to discount and discount and discount because they can so easily absorb any losses they might make from doing that in a country like the UK,” he says.

Amazon has made the public reluctant to accept higher prices. We’re faced with rising staff costs, business rates, rents, without the price of books rising to meet them

Amazon’s price cutting was facilitated in part by the demise of the net book agreement between publishers and booksellers. It set the prices at which new releases were sold but started to break down in the 1990s as Amazon’s journey was just beginning. The agreement was anti-competitive in some respects, but it helped support an industry that plays an important role in the cultural life of the nation. And the shops that benefited from it still competed with each other on service and stock, for example.

The situation facing people like Johns now is that book prices have remained static for 20 years while costs have only gone up.

“Amazon has made the public reluctant to accept higher prices,” he says. “We’re faced with rising staff costs, business rates, rents, without the price of books rising to meet them.”

Necessity being the mother of invention, the surviving bookshop owners have had to diversify to make the numbers add up. Johns has, for example, set up a publisher, also called Mabecron, which has more than 40 releases to its credit, as well as running events and bookclubs. The role played by diversification in the survival of Britain’s independents is a theme picked up by Meryl Halls, who has worked at the Booksellers Association for 30 years, and seen it all. Now managing director, she says: “Bookshops have become community hubs in so many cases. They have diversified what they sell – often including a cafe in the offer, as well as gifts, stationery, kids’ toys, board games and beyond. And they have upped their customer service levels.

“They choose their stock carefully, often focusing on books that are beautiful objects in their own right, curating and displaying them well, and they spend a lot of time building relationships with their customers.”

She says bookshops have “learned to deal with Amazon” but like Johns still criticises it for its “employment, taxation and business practices” and the “systematic discounting of books and subsequent devaluing of them”.

“There may be fewer [bookshops] than there were, but they know how to operate. They are demonstrating high levels of creativity, energy and innovation in reaching customers, building new audiences and selling books.”

Johns speaks of the bookshops becoming hubs for “recreational shopping”. “That’s really the way forward,” he says, noting that the business in high profile titles, best sellers, cookbooks, and celebrity biographies, that were once reliable earners is now Amazon’s. But he also detects a rising willingness to support small bookshops among the public, similar to what has happened with record shops.

And like Record Store Day, which sees customers flocking to them to pick up limited edition vinyl releases, bookshops have events of their own, such as World Book Day. “There definitely has been a love-a-bookshop groundswell,” muses Johns. “How strong it is time will tell. It’s still tough out here but I do sense a slight hesitance from our customers to buy from Amazon.”

The secondhand trade has been less directly impacted by the giant’s rise, although it has muscled in on that part of the business too through Amazon Marketplace and its ownership of AbeBooks.

The latter is a portal through which purveyors of rare books from around the world list their stock. You wouldn’t know it was an Amazon company through browsing the site, but it is.

And it is through a recent decision that it made that the sector demonstrated that even Amazon’s power has limits.

The site had told bookshops in countries including Hungary, the Czech Republic, Russia and South Korea that it would cease supporting them, citing migration to a new payment service provider as the reason.

In response, more than 550 booksellers in 26 countries put more than 3.5 million titles “on vacation” from its listings. A meeting between the International League of Antiquarian Booksellers (Ilab), an umbrella group for national trade bodies, and AbeBooks saw an agreement reached to reinstate the affected booksellers.

“This historic, unprecedented action is a success for us all,” said Ilab president Sally Burdon in response.

Secondhand bookshops have suffered from a reduction in numbers, partly as the result of some of the same sort of pressures that have contributed to the demise of many high street sellers of new books: rising rents, staff costs, and especially business rates.

Despite these difficulties, Ian Irvine, a former colleague of mine at The Independent, nonetheless decided to enter the trade just over a year ago. I initially thought he’d lost his marbles. Why would anyone embark on such a venture in the current climate?

Yet, just over a year after having purchased Bookshop on the Heath in Blackheath, southeast London, with money willed to him by his parents, he’s still in business and seems upbeat and cheerful when I meet him at his shop.

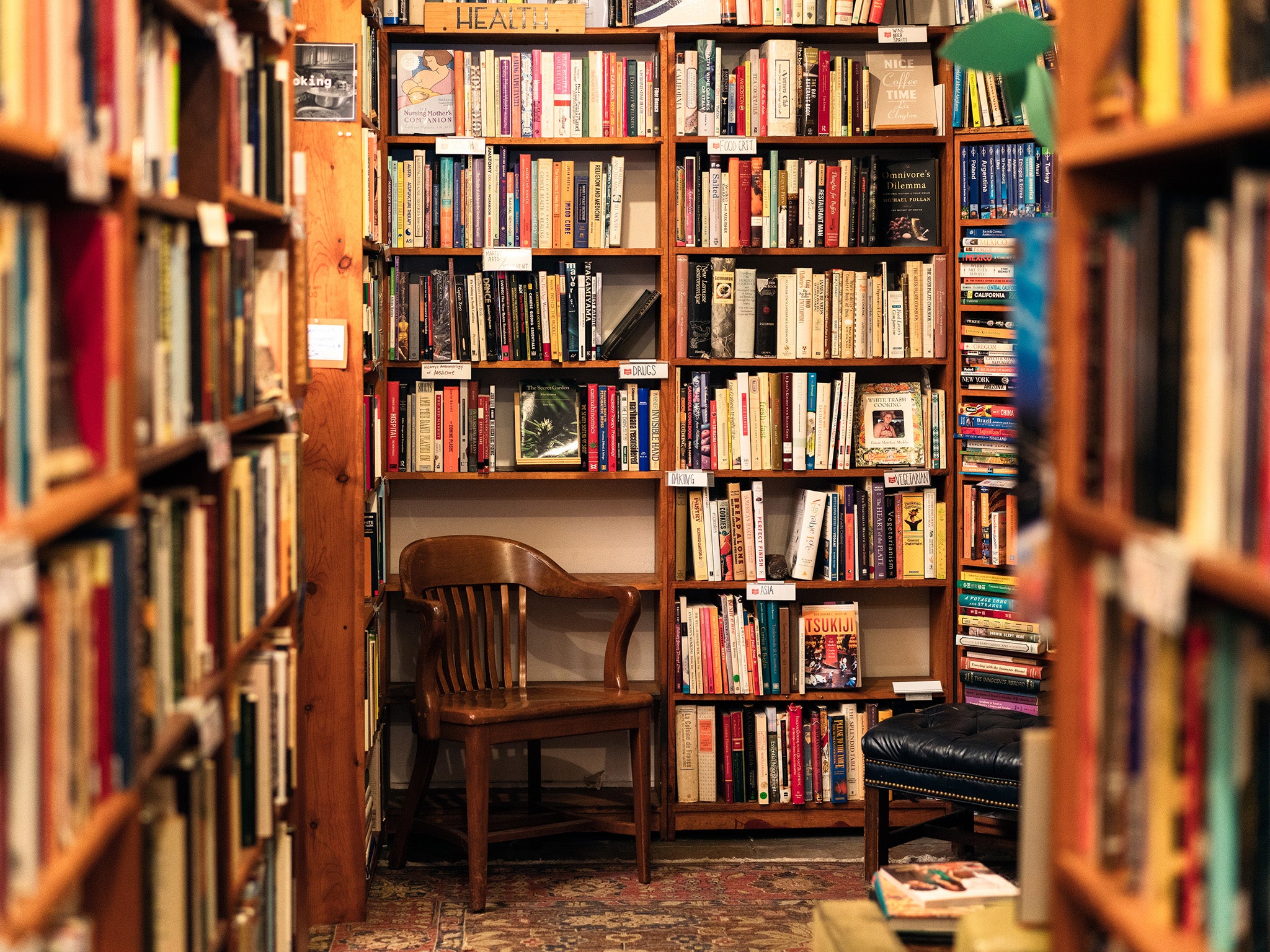

Tall, bespectacled, and well spoken, he does rather have the look of a bookseller which makes him a fitting addition to the shop’s considerable ambience. It’s filled with ancient-looking hardbacks, maps, and posters, with the paperbacks consigned to racks outside the bright green shopfront.

It’s the sort of place that would, in fact, make a fine location for a remake of the Roberts/Grant film if it were renamed “Blackheath”, and it does occasionally get used for filming. Fans of the BBC’s Spooks may recognise it.

“The internet is great if you know what you want,” Irvine says. “But if not you go into a bookshop and you find things you didn’t know you wanted. You discover things. That serendipity is really what bookshops are about.”

He is lucky in that the owner of his freehold wants to have a bookshop in it – it’s a condition of the lease – and was willing to agree a commercial but favourable rental deal. Business rates are a bugbear of his too. He pays £770 a month, although it will fall next year, and says he needs to take in around £3,500 month in total to break even, a significant sum for a small shop. As such he’s aiming to move the business more in the direction of antiquarian and rare books which fetch higher prices and offer a better margin than more everyday offerings. The internet is an important source of custom for these, so he’s made his peace with Amazon and has plenty of stock listed on AbeBooks.

You discover things. That serendipity is really what bookshops are about

“Just about every secondhand bookshop in the world lists things on it,” he says, underlying its importance. “I use it all the time because it tells you what people are offering and how much for. It’s incredibly useful and every week I’ll dispatch something internationally.”

A recent example saw him receiving an e-mail from the Salzburg Festival in Austria, which was after one of his listings, Harmonic Variations, a signed book written in 1909 that had been in the shop for 15 years.

“I had the only copy that’s currently available in the world and in the end it went for £425,” he says. It’s the sort of sale that plays a big part in the shop reaching its monthly target. But so do framed maps of the local area, which do very well with its prosperous residents.

Diversification is all. Nicholas Dennys, a nephew of the author Graham Greene, is a veteran of the trade who started out on market stalls before graduating into shops. His Dennys, Sanders & Greene Rare Books now does most of its trade online. He says the financial crisis hit his part of the market hard. “Prices dropped by about half in real terms and they’ve only recently started to recover.” But he also cites regulation and rates as big problems for small booksellers generally.

Tim Bryars serves as spokesman for the Antiquarian Booksellers Association as well as running Bryars & Bryars in London. He says there are at least as many people selling rare books in the UK as there have ever been, but not all of them work full-time or from a shop, not least because of what he describes as “the extraordinary hike in business rates over the last 20 years”.

“Amazon has a toe in the antiquarian and secondhand market as it owns AbeBooks, which was the object of a successful vendor revolt last year. However, many of our members continue to find AbeBooks a useful platform, one of many ways to buy and sell. ABA membership is steady, with new members joining every year (at least as many as retire), and we see new shops opening too,” he says.

“The challenges and opportunities the internet has brought are different for different sectors of the book trade. In some ways it has become a more competitive world, but booksellers and customers can find each other in ways which were impossible 25 years ago.”

Halls also signs off on an optimistic note about the trade in new books.

“Very often bookshops are the best of their high street, connecting with other retailers in community endeavours like Totally Locally and bringing authors to town for live events. Bookshops are newly confident, and more of them are thriving – but we need to be vigilant about the relentless pressure on high street costs and continue to fight for a level playing field for bookshops,” she says.

Amazon can’t be avoided, but the market is, it seems, finding ways to live with it, and draw some of its customers into coming back through their doors. So Hollywood, with its never-ending appetite for remakes, should find there are still independent booksellers around if we have to put up with a second run of Notting Hill.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments