The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Path of Blood: New documentary explores jihadi extremism, radicalisation and al-Qaeda's target, Saudi Arabia

Aimen Dean was just 19 when he pledged allegiance to Osama bin Laden – until the brutal reality of mass murder led him to be flipped by the Qataris, and return to Afghanistan as a spy for MI6

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In the years following 9/11, documentaries such as Restrepo and Armadillo gave us intimate and unflinching accounts of the daily lives of troops fighting the war in Afghanistan.

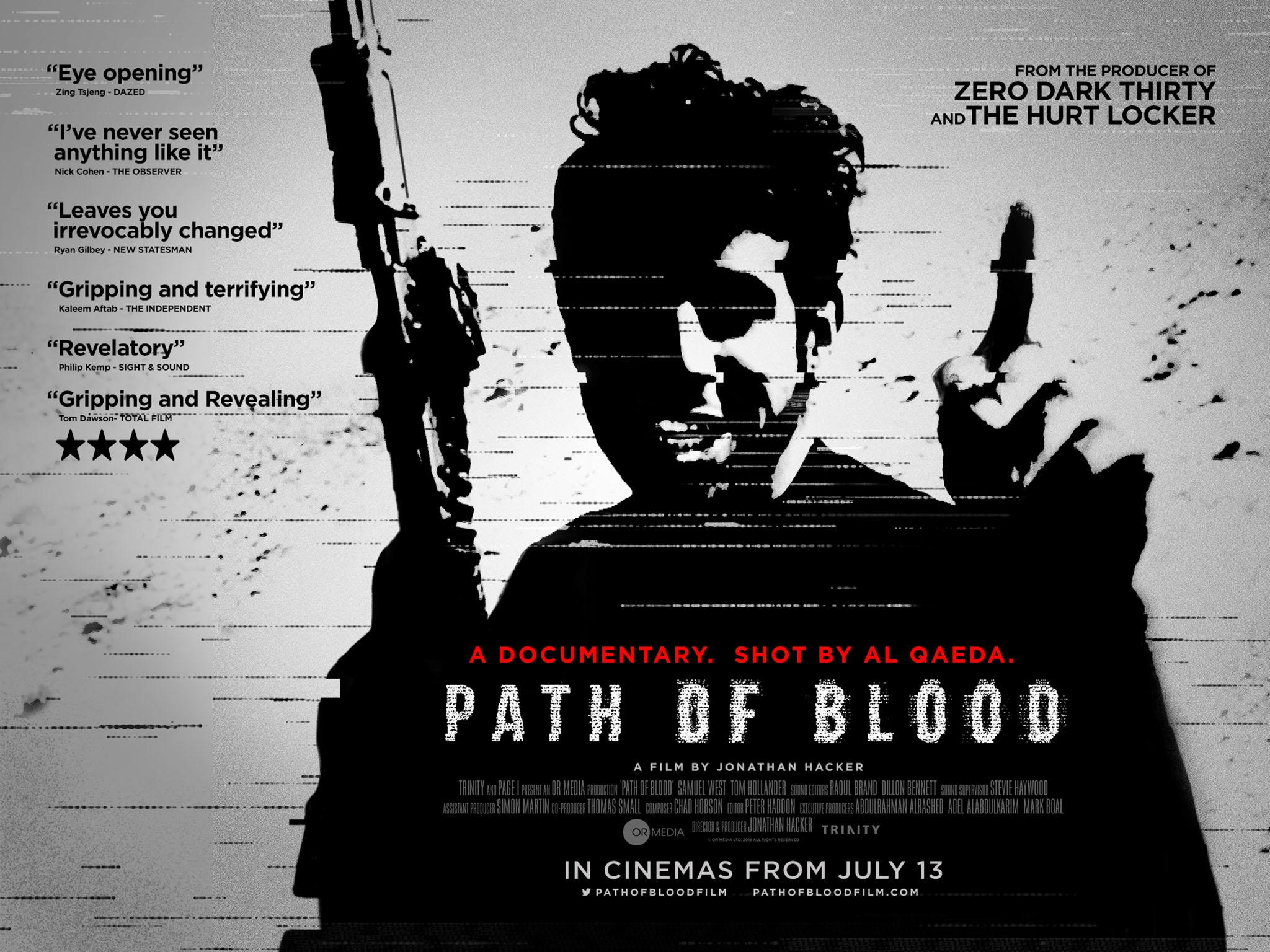

Jonathan Hacker’s Path of Blood now offers a similar kind of insider’s eye – only this time we’re taken behind the scenes of al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, during their bid to topple the Saudi government in 2003.

Raw, uneditorialised footage, shot by the jihadis themselves, captures the young men at play and in action, complicating the popular image of fanatical “death to the West” extremists. The overall effect is harrowing and fitfully hopeful.

By showing how the Saudis quashed the insurgency using tough counter-terrorism measures, and then offered a rehabilitation programme to jihadis capable of changing, the film offers a valuable lesson about how to address the frightening phenomenon of radicalisation and terrorism.

Even then I saw that this would take us into bloodshed on a scale that had never been seen before in modern Muslim history

Nevertheless, you are left wondering what led some of these fresh-faced youngsters, who seem so familiar, to a point where they’re able to take innocent lives without blinking, and sacrifice their own despite having barely started them.

Seeing them as human beings is crucial to understanding, says Aimen Dean, a Saudi-born security consultant who advised on the film.

“If you don’t recognise them from the beginning as humans, how can you begin to find a cure? If we dehumanise them, we end up like them, because they dehumanise their enemies too.

“So, in order to counter their ideology, or the spread of their ideology, which we’re showing doesn’t spare anyone, first of all you have to humanise them.”

Dean should know. When he was 19, he sat with Osama bin Laden in Kandahar, Afghanistan, and pledged allegiance to his cause. As a member of al-Qaeda, he got to know almost all the leadership; he taught Islamic theology and history and the essentials of religious practice to recruits, and worked as an apprentice to a notorious bomb-maker, Abu Khabab.

However, his loyalty was shaken in 1998, when explosions at two US embassies in east Africa killed 224. They weren’t his bombs – “I never built a device outside of Afghanistan, and they were all for training” – but at the same time, Dean says, “I felt I was part of that. Therefore I needed to help dismantle it.”

After weeks of soul-searching, Dean decided to leave al-Qaeda. He travelled to Qatar, on the pretext of requiring a medical examination, whereupon landing he was immediately made “a guest of the Qatari intelligence services”.

Given the choice of being handed over to their French, American or British counterparts, Dean chose the latter. After six months of debriefings, he flipped, and returned to Afghanistan as an MI6 spy.

The attacks had been a wake-up call – not only because of the massive loss of life, but because of how al-Qaeda justified the action using a 13th-century fatwa which sanctioned the killing of captured Muslims, who were being used as human shields by Mongol invaders laying siege to their cities.

The fatwa applied to a defensive situation where the deaths were unavoidable. Al-Qaeda twisted it, says Dean, to create a precedent for attacking locations “where there is certainty that civilians will die”.

“That really alarmed me, because this is basically a blank cheque to disregard human life – in fact, to maximise casualties rather than minimise them.

“So even then I saw that this would take us into bloodshed on a scale that had never been seen before in modern Muslim history.”

Dean had a feeling as early as 1996 that the Arabian Peninsula was in al-Qaeda’s cross-hairs, which later grew into the realisation that his homeland, Saudi Arabia, was Bin Laden’s “main target”.

“He used a Saudi to drive the van into the embassy, and then chose 15 people from Saudi Arabia for the 9/11 attacks ... He wanted the world to turn against Saudi Arabia to destabilise the regime, so that the replacement for the Saudi royal family will be an even far more radical version of Islam.”

Of course, al-Qaeda and its ilk need a constant flow of fresh blood to be effective, and another of Dean’s roles was to find new members. “Saudi Arabia and places like Yemen, Kuwait, Jordan, and, of course, the Muslim communities in Europe and North America – these were fertile ground for recruitment,” he recalls.

If we dehumanise them, we end up like them, because they dehumanise their enemies too

In the past they worked “peer-to-peer”, which was like “having a fishing rod, and you catch a fish one by one”. Now, the web has given them “a net with which you can catch thousands of fish in one go”.

“First it was through dedicated websites. Then discussion forums. Then it was video sharing platforms. Then after that, social media,” says Dean.

With a single Facebook post, Tweet, or written document, groups could suddenly reach into countless homes simultaneously. “So the exponential growth in the number of jihadis was due to the internet playing a vital role.”

Many factors drive radicalisation – and the process isn’t the same for everyone – but one that Dean always noted was a need people had to redeem themselves.

“Islam is a guilt-based religion, just like Catholicism,” he says. “But unlike Catholicism, you do not have a priest who you can confess to and gain absolution, so therefore you need to find a way to redeem yourself. So jihad is always sold by groups like al-Qaeda and Isis as the shortest path to redemption and the shortest path to heaven.”

Another powerful driver is people ceasing to identify with their “nation state”. “So they’re no longer Saudi or Jordanian or Qatari or Kuwaiti; they’re Muslim first, Muslim second, Muslim last.

“And therefore if their identity, which is Islam, is under attack by forces, the West in particular, which they deem to be at war with Islam, they need to defend their identity. They need to defend their honour. They need to defend their faith.

“So there is a need for redemption and there is an anger against what they see as American/Western hegemony. These are some of the factors, I believe, that are contributing to the radicalisation.”

Dean’s own journey began in 1992, at age 14, when his maths teacher went to Bosnia to help defend Muslims from Serb aggression, and died. “With that, a conflict that was raging thousands of kilometres away suddenly became a reality in our own classroom,” he says.

Over the next two years, he watched videos about the war and men going to fight jihad. When he heard that the brother of a close friend was joining the mujahideen, Dean asked to go with him. “I felt that I was ready. I just needed the trigger.”

Although only 16, he was “completely at peace” with the idea that he probably wouldn’t return.

“You believe that your life should count for something and that you need to live an honourable and a meaningful life, even if it’s short, rather than a meaningless, dull life, even if it’s long. So it’s the desire to be a part of history, a desire to find that bigger purpose in life that makes your life have meaning.”

The war was ugly, but it also felt like an extreme adventure to the young Saudi, who at home had been a bookish, bespectacled nerd. Putting on a military uniform and carrying an AK-47 for the first time gave him “a sense of empowerment and a sense of destiny that wasn’t there before”.

“You feel a sense of power after feeling powerless ... It was intoxicating.”

Consequently, when he was asked to go to a training camp in Afghanistan, Dean leapt at the chance. He wanted more.

“War changes your soul and war really makes you feel you cannot go back to a normal life,” he says. “So once you feel that you are on this path, you are on this path. The vast majority of people hardly leave it.”

Today, Dean identifies with the young men in Path of Blood as someone he might have become. “If I didn’t change my mind, if I didn’t decide that this path was no longer for me, I could have ended up as one of those engaged in this fight.”

Where did he find the courage to get out? “Disillusionment is always a good bridge towards a normal life,” he says laughing. “When you become disillusioned, and you think maybe this is not for me, that helps a lot in terms of pushing you towards forcing yourself to go towards a normal life.”

But this wasn’t to be – at least not right away. When he went to Qatar, he says, “I thought, naively, that I would enrol in the university, become a history teacher, and end up in a situation where I can get married, have a family, and that’s it.” After he was detained, he realised: “There is no normal life for me anymore. This is it.” Thus it was easy to say yes to working for the British. “I thought, ‘I want to go back to Afghanistan. I really want to feel the thrill again.’”

His cover was accidentally blown by an American journalist in 2008, but not before Dean had helped to foil a number of potentially deadly al-Qaeda plots, including a poisonous gas attack on the New York subway.

He’d operated out of Bahrain for part of the period covered by the documentary, passing on intel about how al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula functioned, and their relationship with the al-Qaeda leadership in Iran.

To his dismay, though, he was unable to stop a lethal car bombing at a compound in Riyadh, during Ramadan, in 2003, which features in Path of Blood, because while he could tell the security forces an attack was going to happen in the city on a particular night, he didn’t know where.

There were times between the insurgency in Saudi Arabia and now, when al-Qaeda became an almost forgotten force as Isis grabbed the headlines. In fact, four years ago it “reached the bottom”, says Dean. “But after the bottom there is nothing else for them except going up.”

Which is indeed where they have been heading. They stepped up their fundraising and recruitment and regrouped, and now, according to some assessments, al-Qaeda and its affiliates are the world’s top terrorist threat.

Dean believes that within two years, they will “mount some sort of credible attack to try to reclaim the mantle of jihad and also to launch Bin Laden’s son Hamza onto the world stage, as the new young leadership of al-Qaeda emerges”.

Path of Blood is history then, but also a terrifying look at a problem which isn’t going away, and whose foundation in theology, ideology, and distorted history makes its spread difficult to counter.

“It’s incredibly complex,” says Dean, “and the idea that there is an easy fix for this is ludicrous. It’s fantasy.”

Path of Blood will be released in cinemas 13 July, and available on demand on iTunes 16 July

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments