New Brothers Grimm fairytale written by artificial intelligence robot

The Brothers Grimm might have been dead for more than 150 years, but they’ve just released a new fairytale... with a little bit of help from artificial intelligence

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The Brothers Grimm have been dead more than 150 years, but they recently released a new story with a little help from artificial intelligence.

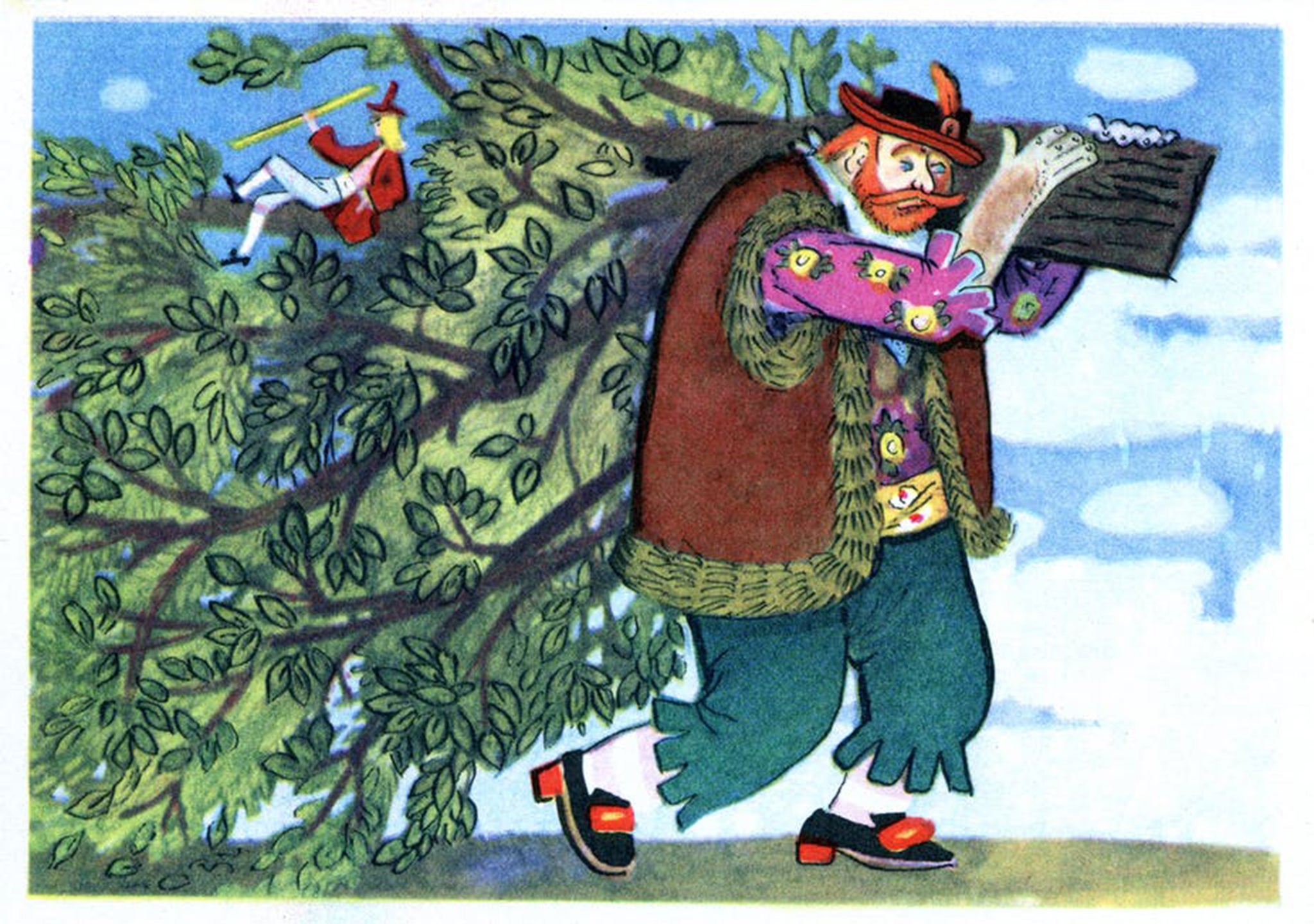

The Princess and the Fox was created after a group of writers, artists and developers used a programme inspired by predictive text on phones to scan the collected stories of the Brothers Grimm to suggest words and similar phrases.

Human writers then took over, to help shape the AI’s algorithmic suggestions into the latest Grimm fairytale.

The new tale tells the story of a talking fox who helps a lowly miller’s son rescue a beautiful princess from the fate of having to marry a horrible prince she does not love.

But here’s the thing, the Brothers Grimm didn’t actually write their fairytales in the first place. They collected them – from friends, servants, workers and family members. Fairytales, of course, have always been retold.

They come alive in the telling – whether that’s a child listening to an audio book in the car, watching Snow White and the Huntsman on DVD or singing along to Shrek The Musical in the theatre.

The Grimms’ fairy stories were first published in 1812 and have never gone out of print. The Grimm Brothers were involved in the struggle for German independence. As part of the case for nationhood, they wanted to prove that Germans, as a distinct people, had their own folklore.

They were political campaigners too, and among the Göttingen Seven who refused to take an oath of loyalty to the new king of Hanover when he rejected a more liberal constitution.

They lost their jobs as a result and Jakob Grimm – like many characters in the fairytales – had to go into exile.

Since then, Grimms’ fairytales have been translated into 100 languages and retold again and again. They have inspired thousands of other works, from Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber to The Simpsons’ “Treehouse of Horror”.

Jakob Grimm wasn’t just a collector of folk tales either. He was also a philologist (someone who studies language) and lexicographer whose work is still influential today.

As well as being a master storyteller, the ideas he developed are still being researched in universities. Grimm’s law, named after Jakob Grimm, looks at how sounds change as they pass from one language to another – “P” tends to become “F”, while “G” becomes “W” and so on.

Happily ever after

The Grimms’ fairy stories are still passed down through generations. And even though the cast of princesses and swineherds seem a very long way away from the world most of us inhabit, the stories are still a crucial part of our cultural heritage.

The stories the brothers found in northern Germany at the beginning of the 19th century now belong to everyone.

As a child growing up in Oxford, my father – a refugee from Germany and, like Jakob, a philologist – used to tell me the Grimms’ story of The Frog Prince on our Sunday walks in the grounds of Blenheim Palace.

In my father’s version of the tale, the princess first met the frog by the lake – in reality built by Capability Brown for the first duke of Marlborough – when she dropped her favourite plaything, a golden ball, into the water.

When they lived happily ever after, the couple commemorated their meeting by putting golden balls on the top of Blenheim Palace. Now when I think of the story I think of Blenheim Palace, and I hear the splash of the frog in the lake, just as I thought I heard it long ago as a child.

This is exactly what stories can do, they fold all of their tellers and places together – and therein lies their mystery and their magic – once a story exists, it changes how we experience the world. And that will be the only test of “the new Grimms’ tale”, The Princess and the Fox – whether it will be retold and come to life in the telling.

Adam Ganz is a reader in the Department of Media Arts at Royal Holloway. This article was originally published on The Conversation

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments