Digging deeper into the luxury basements of London’s super rich

Basement developments are on the rise among the capital’s more affluent residents, with planning permission granted for thousands – including one with a built-in beach

In 2008 there were estimated to be 8.6 million “high net worth individuals” – people with $1m (£761,000) or more of investable assets – in the world, but by 2016 this had increased by 92 per cent to 16.5 million, according to the World Wealth Report.

The geographical distribution of this population is highly concentrated: 4.795 million in the USA; 2.891 million in Japan; 1.280 million in Germany; 1,129,000 in China; 579,000 in France and 568,000 in the UK (compared to 362,000 in 2008). Some half a million of these people live in and around London, in a set of tightly circumscribed neighbourhoods.

All of this wealth sloshing around London has had myriad consequences for the built environment. Perhaps the most evident has been the appearance of a large number of “super-high”, “super-prime” residential towers – vertical urban housing that has become something of an elite preserve.

But the wealth that has not found its way into the changing skylines of the city has still had major impacts on the existing built environment. Many high-end properties have been transformed as super-affluent newcomers commission often brutal structural conversions of older properties into “state of the art” living spaces. Maximising the size of all interior spaces and infusing them with exterior light has now become de rigueur, as have various design and technological “solutions” to matters of privacy and security.

But, in many areas of “super-prime” London attractive to “super-rich” elites, the nature of the original architecture combined with planning restrictions often makes it very difficult to extend properties laterally, or to add additional floors on the top of properties. And so, for some, the only “solution” has been to go down.

Consequently, residential basement developments in the wealthiest parts of London have increased markedly in recent years. The construction of this new subterranean London for the super-rich has been the subject of much comment but, until recently, little systematic investigation.

Our new research now suggests that such developments are emblematic of how London is changing. Along with residential highrise luxury towers (“luxified skies”) sprouting up across the city, we are also witnessing an epidemic of “luxified troglodytism” – super-rich households extending their properties in a subterranean direction by way of basement excavation.

Digging down

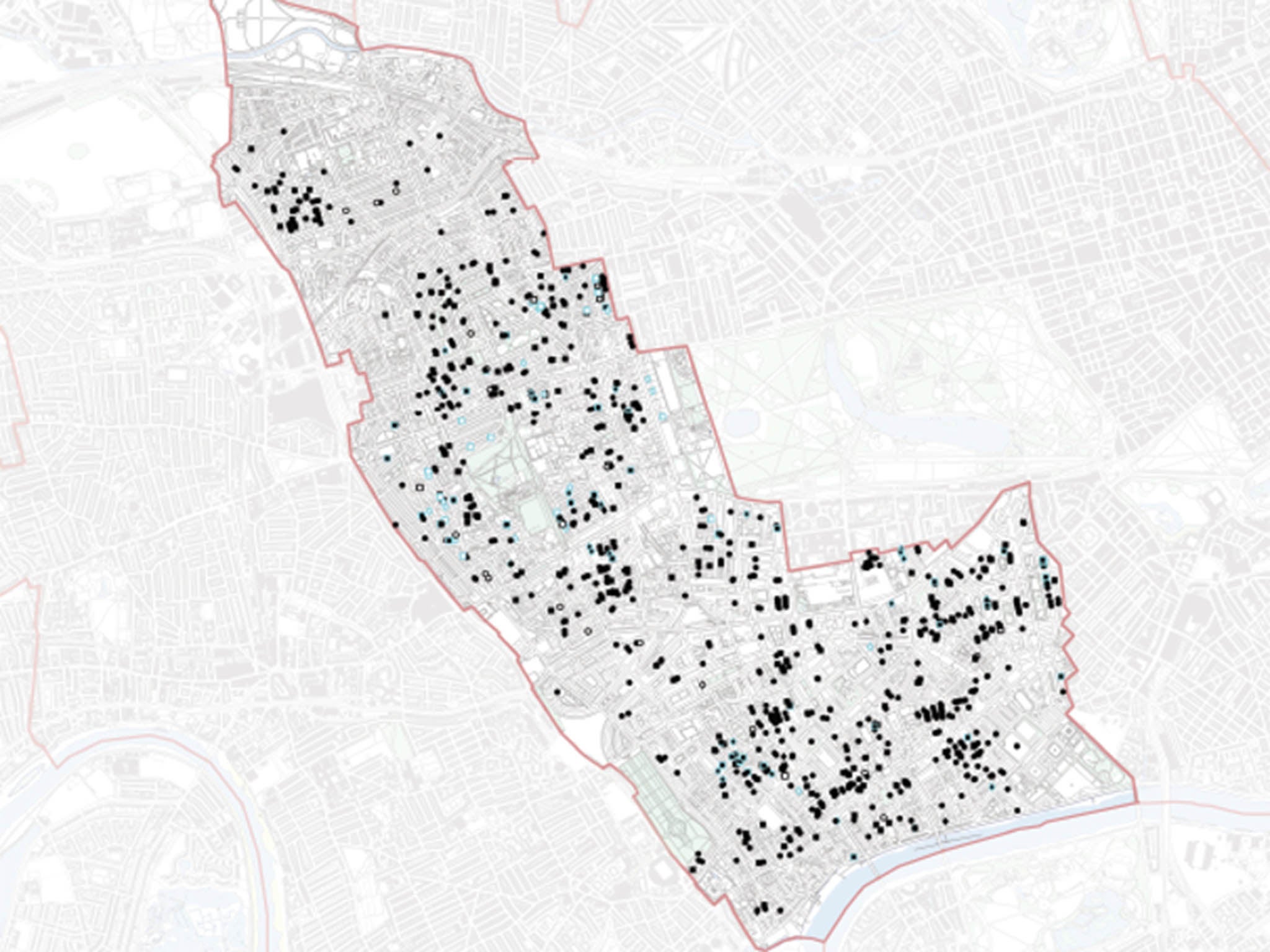

In order to investigate this phenomena, we extracted data from planning portals for the seven London boroughs of Camden, Hammersmith and Fulham, Harringay, Islington, Kensington and Chelsea, Wandsworth and Westminster – all localities that cover core “super-prime” London – between 2008 and the end of 2017. We discovered that 4,650 basement developments had been granted planning permission.

Hammersmith and Fulham has the greatest number – 1,147 over the decade – followed by Kensington and Chelsea with 1,022 and Westminster with 678. We would classify the great majority (80.7 per cent) as “standard” single-storey excavations – but 16.9 per cent (785) were “large” two-storey (or the equivalent in volume) constructions and 2.4 per cent (112) could only be described as “mega” basements – three storeys or more deep (or the equivalent in volume).

It is the 785 large and 112 mega-basements that should be the real focus of our interest. These almost 900 excavations are on a different scale to the standard constructions. Together they contain: 367 swimming pools, 358 gyms, 178 cinemas and 63 staff spaces. We also found 14 car lifts, seven art galleries, two gun stores – and one owner who admitted to building a “panic” room.

Some of these basements can take many years of disruptive construction to complete and concerns have been raised about their environmental impact.

Perhaps the most “luxified” development we discovered was one that had been granted planning permission in Holland Park in 2013 under a large semi-detached house. It consisted of a new three-storey basement under the entire property and part of the rear garden. It includes a staff kitchen, staff bedroom, six WCs, a gym, a media room, a family room, a family kitchen, a guest bedroom, a guest kitchen, a laundry room, a drying room, a sauna, a steam room, two shower rooms, a jacuzzi, a plunge pool, a pantry, a full-sized swimming pool and a beach. Yes, a beach.

In this particular basement development the “water-related” features were of a roughly equivalent volume to an average new-build property in England. Some of the super-rich swim, bathe and steam subterraneously in spaces equivalent to what the rest of us might consider adequate to undertake all of our domestic activities in.

All this shows that there has been a significant increase in the number of larger basement excavations in the past 10 years. Such widespread development of subterranean London is an important component of broader changes in the built environment that have occurred since the 2008 financial crash. The “luxified skies” that Londoners are more used to are highly visible reminders of elite power – but these deluxe basements which, in aggregate, are equivalent in depth to 50 Shards, are also an important aspect of the type of city that London has become.

The super-rich continue to have a significant impact on London – it is simply not so noticeable any longer. Wealth is burrowing underground, rather than just reaching for the skies.

Roger Burrows is a professor of cities at Newcastle University. This article first appeared on The Conversation

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments