A Life in Focus: Mehdi Bazargan, religious moderate who lasted nine months as Khomeini’s first prime minister

The Independent revisits the life of a notable figure. This week: Mehdi Bazargan, first prime minister of the Islamic Republic of Iran, from Saturday 21 January 1995

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It is possible to identify two categories of men among those who have contributed to the development of modern Islamic political thought in Iran.

The first, men such as the late Ayatollah Khomeini, come from a clerical environment; the second – a more recent breed – are lay intellectuals who have taken the leading role in defining and expounding the Islamic religious creed.

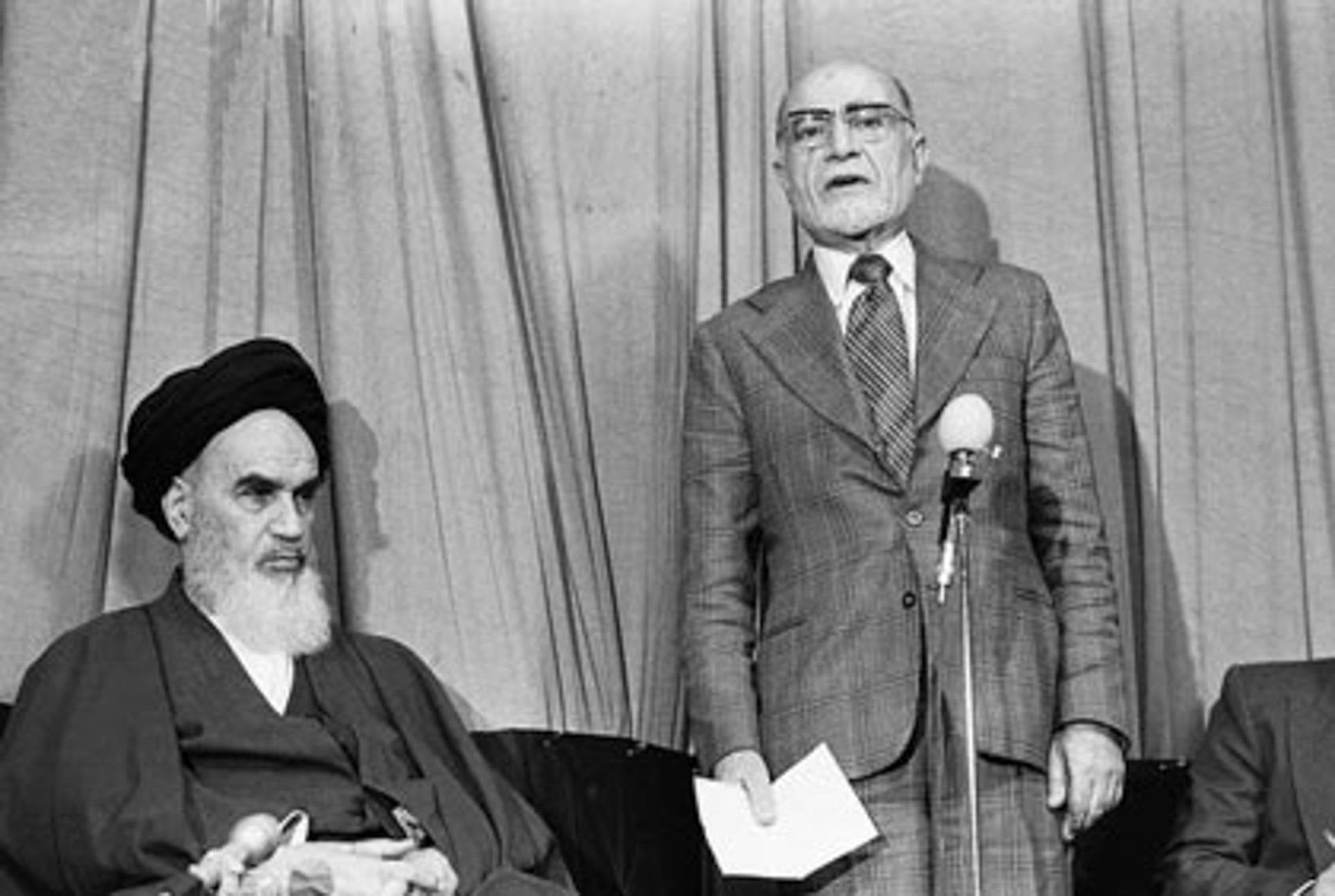

Mehdi Bazargan, the first prime minister of Iran following the 1979 revolution, well known as a representative of modern liberal Islamic thought and an emphatic supporter of constitutional and democratic politics, was one of these.

Bazargan’s father, Hajj Abbasquoli Tabrizi, was a self-made merchant, deeply religious, but not wholly traditional, and active in bazaar guilds. Bazargan’s education was privileged.

The secondary school he attended was one of the first modern schools in Iran. At the age of 19 and at government expense he was sent to France, where he studied thermodynamics. There he frequented the popular Catholic and republican circles of the Third French Republic.

In 1936 he returned to Iran, to enter government service and the teaching profession as a lecturer in thermodynamics, before moving into the private sector. But Iran’s experimentation with political tolerance in the period 1941-53 brought Bazargan into the political field. He began his activities in a small mosque association (Kanun-e Islam) and was involved with the newly founded Islamic association of students.

He was instrumental in the creation and running of the Engineers Union, became active in the Iran Party and, through it, in the National Front, where he was appointed by then prime minister Dr Mohammad Mosaddeq to supervise the takeover of the newly nationalised oil industry.

Following the 1953 coup that toppled the national government of Mosaddeq and led to the arrest of the leading National Front cadres, Bazargan directed his energies towards the establishment and running of the National Resistance Movement. He was elected as its executive secretary, a position that he maintained despite being twice arrested, in 1955 and 1957. With the liberalisation period in the early 1960s he participated in the building of the Second National Front.

He took part in the clergy-dominated reform movement in order to establish a new religious leadership code after the death of Ayatollah Hossein Boroujerdi. In 1961 Bazargan and others formed the Freedom Movement of Iran (FMI), of which Bazargan was elected leader. The group did not flourish long. As a consequence of criticising the Shah’s White Revolution, FMI members were arrested and imprisoned. Bazargan himself was sentenced to 10 years’ imprisonment but was released, on a royal pardon, after three.

Following his release and throughout the Seventies Bazargan kept a low profile but was actively involved in a number of intellectual debates – in a dialogue with the clerics on the meaning of government; in a critique of Marxism; and in elaborating a modern interpretation of Islam.

When political controls were relaxed in 1977 Bazargan re-entered the open political arena through the Society for the Defence of Human Rights. An established record of activism in Islamic and national circles promoted Bazargan to the forefront of Iranian opposition circles and it was on this basis that the emerging leader of the revolutionary movement, Ayatollah Khomeini, appointed him as the first post-revolutionary prime minister. In February 1979 and in the hope of reforming the state bureucracy, Bazargan formed his cabinet. His nine-month government was, however, to preside over the greatest defeat suffered by the liberal moderates at the hands of the radical and revolutionary movement.

Following the takeover of the American embassy in Tehran by a group of radical Islamic students supported by Ayatollah Khomeini, Bazargan was forced to resign and to retire into the ranks of the opposition. His most significant contribution to Iranian politics was probably to be in this period when, in the midst of violent conflicts with the state and opposition forces, he guided the FMI towards the development of a liberal political profile.

Throughout the 1980s Bazargan’s insistence on liberal politics was scorned by four groups. First were the modernist/monarchists, who in their apolitical model of social development had no time for Bazargan’s indigenous concoction of open, active, religious and liberal politics. The second group represented the traditional religious community led by the senior clergy, who jealously guarded the mystical world of their creed and saw Bazargan’s notion of democratic rule as a threat to their elitist concept of the right of the clergy to interpret the religious text.

The third group which stood against Bazargan was that of the Marxists, including the Islamic/Stalinist Mojahedin Khalq Organisation. This group saw Bazargan as a petty bourgeois Bazaari merchant whose notion of liberalism was rooted in his greed for personal profit. The last, but most powerful, group was that of the radical Islamists, the main benefactors of the 1979 Islamic revolution. They saw Bazargan as the personification of western corruption amongst the ranks of the believers and thus sought to isolate him.

The 1990s could be termed as a period of strategic ideological success for Bazargan and his liberal colleagues. On the one hand the collapse of the Soviet Union and on the other the futility of 15 years of anti- government terrorism and state terrorism had initiated a far-reaching revisionist trend among all political activists. The word liberal was a derogatory term popularly understood to connote a weak, wishy-washy and petty opportunistic mentality in politics. Almost all Iranian political groups sought to present a liberal image of tolerance and moderation.

In the more than 50 books and pamphlets that Bazargan left behind, he argued for this change in public perception. He was among those few who helped the Iranian people better understand constitutional and democratic government.

Mehdi Bazargan, Iranian engineer and politician, born 2 September 1908, died 20 January 1995

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments