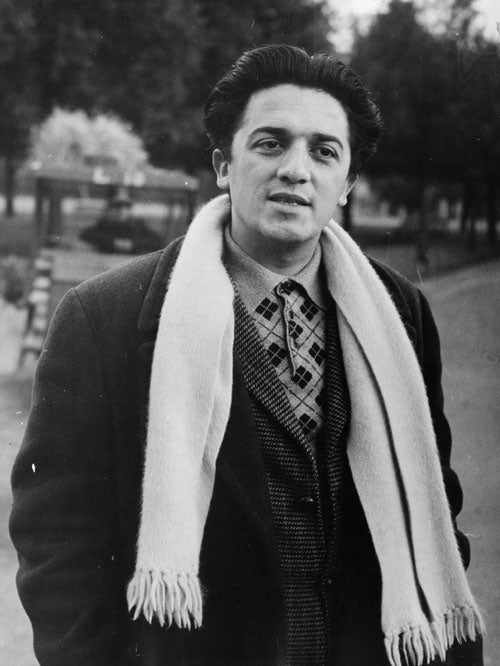

A Life in Focus: Federico Fellini, Italy’s maestro of cinema

The Independent revisits the life of a notable figure. This week: Federico Fellini, from 1 November 1993

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In 1971 the veteran American film-maker Frank Capra called his autobiography The Name above the Title. Though that may seem unbecomingly immodest, it was in fact historically justified, as a reflection of the fact that in the early Thirties, when he was gradually consolidating his reputation, Capra was virtually the sole Hollywood director whose name was perceived, by critics and public alike, as an asset, almost as a production value – a name, therefore, which wholly merited its unique prominence on the billing of his films. How times have changed.

These days practically every film-maker of note (or, frequently, of mere pretension to note) will ensure, contractually if need be, that his name is emblazoned above the title, and it is thus a measure of the quite exceptional prestige long enjoyed by Federico Fellini that his name often was the title. Fellini Satyricon, Fellini Roma, Fellini’s Casanova – never, perhaps, in the entire history of the medium, has a series of films been so intimately, exclusively, identified with the man who directed them.

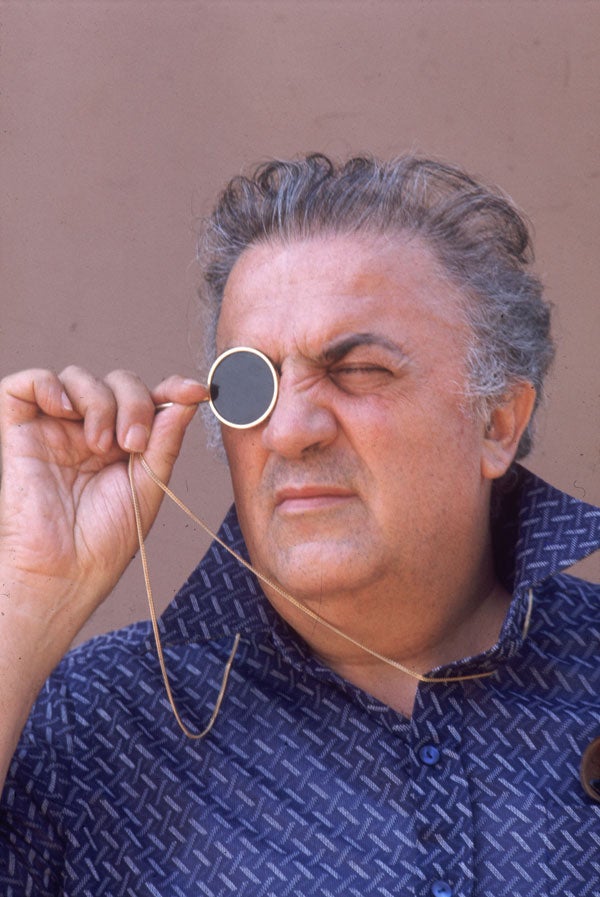

But then, never in the history of the medium has one had the impression (when entering the cinema to see one of Fellini’s films, one of his later films at least) that one was also entering an artist’s head. Fellini was the prime example of an artist capable of transforming himself into a work of art, a man who could, by some mysterious alchemical process, turn himself into a film. So much so that, for any spectator who did not admire Fellini himself, and who was unwilling to embark on his gaudy treadmill of circuses and comic strips, cardinals and carnivals, Barnum and ballet, there was absolutely nothing remaining in his work, neither a plotline nor a performance, not a single “un-Fellinian” element, to which one could respond.

Such, indeed, was the director’s solipsistically personal investment in his own body of work that one tends to imagine, in retrospect, that the Maestro himself was as ubiquitous on the screen as off it. Actually, it was only in three of his films that Fellini made extended appearances, I Clowns (The Clowns, 1970), Roma (1972), and, his penultimate work, Intervista (Fellini’s Interview, 1987, and in Britain released only as a video). Otherwise, he had recourse to a series of rather flattering alter egos, most famously Marcello Mastroianni (who increasingly came to resemble his creator, just as Jean-Pierre Leaud increasingly came to resemble Truffaut) in La Dolce Vita (1959), 8½ (1963), La Citta delle Donne (City of Women, 1980), Ginger e Fred (Ginger and Fred, 1986) and, finally, confronting his own mirror-image face to face, Intervista.

Unusually, too, when several of his films went out on international release, their titles were left in the original language, almost as though there were a serious risk of their sounding not just less Italian but less indelibly “Fellinian” in translation. Thus I Vitelloni (1953) has never been known as The Loafers, La Strada (1954, the film that established him) as The Road, Il Bidone (1955) as The Swindle, La Dolce Vita as The Sweet Life nor Amarcord (1973) as I Remember. (That last title was half-invented, half-derived from “amarcor”, a word in Romagnola patois: it is probable, though, that its primary appeal to the director lay less in its sense than in its sound, which he liked to compare to that of Kurosawa’s Rashomon.)

Fellini’s films may be said to distil the very essence of cinematic spectacle; and, critical cliche as it may be, it has become impossible to refer to those films without equally referring to their ultimate source of inspiration, the circus. The circus, however, not only as a spectacle but as one of the last truly collective experiences. Part of what makes his work so pleasurable is our vivid sense, simply by watching one of his films, of what it must have been like to be involved in its creation.

It’s not too fanciful to suggest that we actually feel transported to the vast, draught-haunted sound stages of Cinecitta, with actors, extras, freaks, sycophants and hangers-on, the by now familiar fauna and flora of Felliniana, appearing to enjoy absolutely equal status with one another; with the relaxed and negligent, on occasion infelicitous but always festive and carnivalesque mise-en-scene of the completed work tendering the spectator what he or she cannot help suspecting is a fairly transparent mirror-image of the noisy, fractious, exuberant caravanserai that was the shoot that both preceded and engendered it; with above all, the cast’s and crew’s faith (in the film’s future in the Maestro’s own genially tyrannical presence) exuding from every pore of the screen.

Every film, of course, also constitutes a documentary of its shoot, but Fellini’s actually function through a sometimes latent, sometimes overt acknowledgement of film-making as a communal undertaking, in so far as they contrive to obscure the immemorial distinction between those in front of the camera (the cast) and those behind it (the crew), as equally between those up there on the screen and those of us down here, so to speak, in the auditorium.

Federico Fellini was born in Rimini, on Italy’s northern Adriatic coast, in 1920, into a middle-class family (his father was a salesman), and from his infancy was fascinated by the circuses, fairgrounds and music halls which played a prominent part in the seasonal routine of that pleasant resort city. As he was to become one of the most overtly autobiographical of film-makers – “If I were to make a film about the life of a flatfish,” he once remarked to an interviewer, “it would end up being about me” – almost every aspect of his early life can be related thematically to his filmic passions, obsessions and preoccupations. But as, even in casual conversation, the fabled fertility of his imagination would consistently compromise the factual basis of his reminiscences (as is most flagrantly the case with Amarcord, a flamboyantly loving evocation of his boyhood in Rimini), much of that early life is now inextricable from the fantasies that he ceaselessly embroidered around it. It does seem likely, however, that as a seven-year-old child he ran away from boarding school to join a travelling circus – just as, in his late adolescence, he would run away, as it were, to join the cinema.

In 1938, after a few years of an idling, trifling and rather aimless existence as a teenager in Rimini in the company of three or four youths of his own age, precisely the sort of existence he would later portray in I Vitelloni, an existence devoted to listless seductions and the perpetration of coarsely mischievous pranks, and after six months spent in Florence as a cartoonist for a comic-strip magazine (an experience that he would exploit in the first of his wholly personal films, Lo Sceicco bianco, The White Sheikh, 1952, a delightful comedy set in the world of the fumetti, or strip cartoons), he finally found in himself the courage (exactly as does his handsome young analogue in Roma) to stake out a space for himself in the capital.

It was there, during the war, that he was befriended by the elderly actor and music-hall comedian Aldo Fabrizi, who appointed him as his company’s resident “poet”, a position which seemed to encompass that of wardrobe master, scenery designer, personal secretary and even bit actor. This experience, which lasted until the liberation of Rome in 1944, provided invaluable background material for Fellini’s very first feature, Luci del Varieta (Variety Lights, 1950), an affecting comedy-drama of music-hall life co-directed with Alberto Lattuada. And, in the wake of the liberation, he opened his self-styled “Funny Face Shop” in Rome, an arcade supplying American GIs with thumbnail portraits and caricatures (by Fellini himself), candid photographs and voice-recordings, for immediate delivery to the United States. Not only did the store’s instant success make Fellini relatively affluent in a period of extreme material hardship, it was there, by chance, that he met Roberto Rossellini, with whom he would collaborate as scenarist on two of the supreme masterpieces of Italian neorealism, Roma citta aperta (Open City, 1945) and Paisa (Paisan, 1946).

Only two more encounters were necessary for his mythology to be complete.

The first, in 1943, was with the actress Giulietta Masina, whom he would categorically describe as “the greatest influence in my life” and who, of course, would be the unloved and unforgettable Gelsomina of La Strada, a Fellinian cartoon teased into heartbreaking life, Charlie Chaplin reincarnated as a woman. Masina performed for her husband intermittently but regularly throughout his career, as a prostitute in Le Notti di Cabiria (Nights of Cabiria, 1956), a bored middle-class housewife in the almost too gorgeously kaleidoscopic Giulietta degli Spiriti (Juliet of the Spirits, 1965, a clear precursor of Woody Allen’s Alice, just as 8½ inspired his Stardust Memories and Amarcord his Radio Days) and the ageing but still game Ginger of Ginger and Fred (1986).

The other, in 1952, was with the composer Nino Rota, who would write the score of every single Fellini film until his death in 1979. It is even possible to argue that Rota’s death was not only a personal but a professional tragedy for the film-maker. Since what his music, with its irresistibly motoric rhythms and roguishly swooning melodic lines (witty, nostalgic Europeanised paraphrases of Kern and Berlin), called for on-screen was a sort of treadmill trot, part-danced, part-shuffled, with the director’s dramatis personae either advancing laterally along layered planes of movement which appeared as spatially discrete from each other as theatre flats, as in the excursion out to the ocean liner in Amarcord, or propelled by a circusy, conga-like rotation (or Rotation), as during the delirious, Fellinissimus apotheosis of 8½, one might also suggest that Rota was more airily, seamlessly “Fellinian” than the Maestro himself.

The great, defining schism of Fellini’s career came with La Dolce Vita, an extraordinarily lengthy and ambitious satire of contemporary Roman high society which was anathematised both by the Vatican and the Italian government, but also proved a sensation at the 1960 Cannes Festival and became not only a worldwide success but a phenomenon such as the cinema has seldom known. (Its title instantly entered every European language and is still, in English, in common currency.) The Maestro had never been especially interested in straightforward linear narrative, his plotlines, if they can so be called, being always rambling and episodic. But the film which succeeded La Dolce Vita, 8½, “the story of a film director who is trying to pull together the pieces of his life and make sense of them”, in Fellini’s own words, was the first to dispense with narrative coherence of any conventional kind, choosing instead to let fact and fantasy spin indiscriminately through a blender of black-and-white imagery as mouthwatering as a box of liquorice allsorts.

It was a style to which Fellini would remain thereafter faithful – in the eerily erotic Satyricon (1969), a work closer to the tradition of science fiction than to that of conventional historical reconstruction (it was widely compared to Kubrick’s 2001), in the gross, almost medieval 18th century that he devised for Casanova, and in the homage to that communal masturbatorium that the cinema used to be in City of Women, three films in which Fellini’s normally warm Mediterranean lyricism is chilled by a shiver from the void.

These, and other, late works have always divided critics: as far as certain commentators are concerned, the word self-indulgent might have been coined expressly for them. It was Fellini’s own feeling, however, voiced on several occasions, that to limit one’s admiration to his early, more modest films was simply an example of “arrested development”, and history will surely prove him right. For only a pinchpenny soul would denigrate the generosity, even on occasion the profligacy, of the powers of invention which, again and again, he displays in them. He was, in reality, one of the century’s great inventors of forms, and had more ideas than he knew what to do with. If uneven, his achievement was also priceless – a curate’s egg, perhaps, but by Faberge.

Federico Fellini, film director, born 20 January 1920, died Rome 31 October 1993

Gilbert Adair died in 2011

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments