A Life in Focus: Elizabeth Longford, literary matriarch and biographer royal

The Independent revisits the life of a notable figure. This week: The Countess of Longford, from Thursday 24 October 2002

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Elizabeth Longford, who died aged 96, was a creative woman in every sense. Biographer, crusading politician, mother of eight children and a devoted, supportive wife, she inherited her driving genes from her maternal Chamberlain relations, the great Birmingham family which produced Joseph, Austen and Neville.

A benevolent fairy godmother hovered over 108 Harley Street where Elizabeth Harman was born in 1906, endowing her with beauty, brains, energy and an outstandingly happy and optimistic temperament. Her parents were both doctors; her mother qualified but never practised, her father was a noted ophthalmologist. Both were also nonconformists. In her 1986 autobiography, The Pebbled Shore, Elizabeth later described the family ambience as: “Austerity and undemonstrativeness along with powerful affection; puritanism with all the comforts of a middle class Edwardian home; the status conferred by a house in Harley Street offset by the minority creed of outsiders.”

It was all a far cry from the aristocratic, eccentric Anglo-Irish Pakenham family into which she married after winning a scholarship to Lady Margaret Hall in December 1925. Socially and academically she was an outstanding success at Oxford, courted by some the most brilliant undergraduates of the day, including Hugh Gaitskell, who masterminded her social career there.

At Oxford in 1927 she met Frank Pakenham, whom she first saw as a “sleeping beauty”, a magnificent figure in Bullingdon Club uniform draped in deep slumber on a garden chair at the Magdalen College Ball. She became a member of Maurice Bowra’s circle (Bowra, a “confirmed bachelor”, proposed marriage), making friends with John Betjeman and Isaiah Berlin, David Cecil and Stephen Spender among others. She was vivaed for a First in Classics but ended up with a Second. In June 1930 she was celebrated as an “Isis Idol”.

The Brideshead atmosphere of Oxford was followed by a stint in the Potteries tutoring and lecturing for the Workers’ Educational Association. “Stoke became as much a part of me in 1931 as Oxford had been for the past four years,” she wrote. “The working class ethos of Stoke became my own.” Although she was not by nature a rebel, firsthand experience of the Depression swung her leftwards and turned her into a socialist; her name was mooted as a prospective Labour candidate for Stoke.

Meanwhile, Frank Pakenham, working for the Conservative Research Office in London, had been hovering on the brink of proposal, and on 3 November 1931 they were married at St Margaret’s, Westminster. With her marriage, Elizabeth moved into the world of the Bright Young Things, innocently unaware that she was not entirely welcome. Evelyn Waugh was the leader of the opposition, writing unkindly to Nancy Mitford about “Harman”: “I pretend to have schemes [to stop the wedding] but I haven’t any really I just trust in GOD.”

In the end it was God who brought Elizabeth Waugh’s approval when she later converted to Roman Catholicism, but in the meantime Waugh rightly suspected her of turning his aristocratic friend into a socialist.

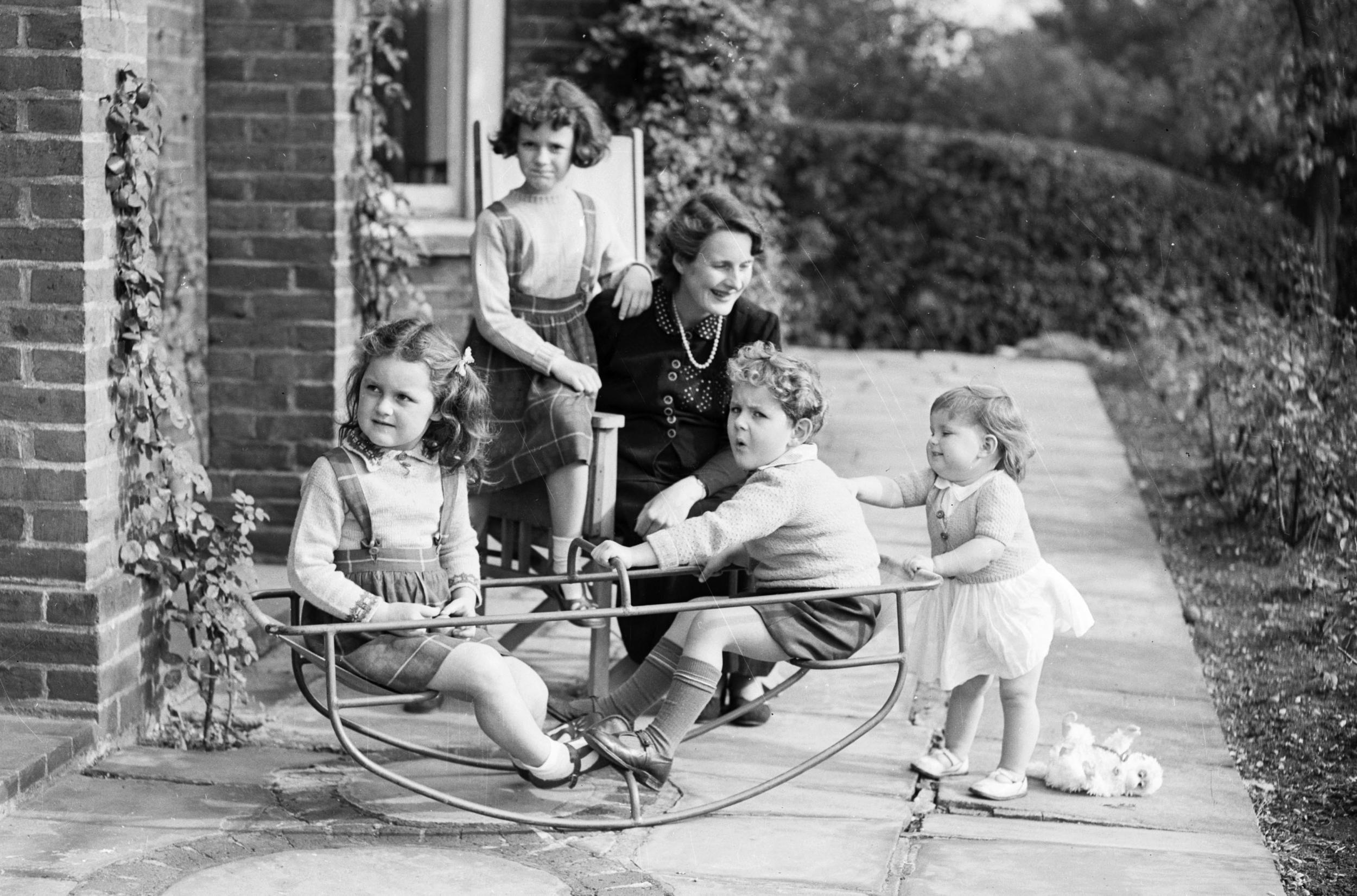

The Pakenhams returned to Oxford in 1934 when Frank became a politics don at Christ Church. Elizabeth joined the Cowley Labour Party and unsuccessfully stood as Labour candidate for Cheltenham in 1935. She had already given birth to two of her eight children, future writers Antonia Fraser and Thomas Pakenham, and was about to embark on a scientific sex-selection programme which ensured the birth of a second son, Paddy, in 1937.

She nursed the Birmingham constituency of King’s Norton for Labour: many of her and Frank’s friends were of the far left. When Philip Toynbee tried to persuade Frank to join the Communist Party, he replied: “Elizabeth decides my party allegiance.” He did not, however, consult Elizabeth before converting to Catholicism in January 1940. In November 1943, Elizabeth’s sixth child, Michael, was born; she had, she confessed, “an addiction to motherhood” which triumphed over her other passion, Labour politics, and when the party tried to issue an edict against further fertility she resigned as prospective Labour candidate for King’s Norton in January 1944.

That year she began to follow Frank’s path into the Catholic Church, which she joined in 1946. The House of Commons still held a lure for her although it was now a vicarious one. “I had failed because I was a woman, and I wanted Frank, my alter ego, to succeed,” she wrote. He succeeded, but as a Labour peer, with the title Lord Pakenham.

Elizabeth’s last child, Kevin, was born in 1947; in 1950 she stood for the last time as a Labour candidate, this time for Oxford, again unsuccessfully, despite the support of such Labour big guns as Gaitskell and Harold Wilson. From 1948 to 1950 her principal role was as mother and government wife.

In the 1950s, her child-bearing years over, Elizabeth Pakenham began her second creative phase. Tempted by Beaverbrook, she became a weekly contributor to the Express, then to The News of the World and The Sunday Times. She was a television panellist on Any Questions. She was tapped for committees. Then George Weidenfeld lured her into publishing, turning her Express articles into Points for Parents (1954). A collection of articles by distinguished Catholics edited by her, Catholic Approaches (1955) followed. Neither of these early ventures was successful; she had not yet found her métier as a biographer.

Her first idea for a subject was her great-uncle Joseph Chamberlain, but failure to gain access to the Chamberlain papers reduced it to just one episode in his life, the Jameson Raid of 1895-96. (She had become interested in Africa through her work for the Africa Bureau.) Jameson’s Raid was published in January 1960 to critical acclaim; AJP Taylor chose it as his book of the year.

Victoria RI, published in the autumn of 1964, three years after Frank succeeded to his brother’s earldom, fulfilled the now Elizabeth Longford’s ambition of writing a book about “a historical woman”. It was a popular success, written with understanding of Queen Victoria’s character and a light touch based on solid research which made it an easy and rewarding read.

Elizabeth’s agent, Graham Watson, proposed Mary Queen of Scots as her next subject, but her daughter Antonia stepped in (“No, I must do Mary”) backed up by George Weidenfeld (“Elizabeth, you will do the Duke of Wellington”). The result was a two volume life of Wellington, The Years of the Sword (1969) and Pillar of State (1972), which was perhaps her finest historical work. A biography of the poet and seducer Wilfrid Scawen Blunt, A Pilgrimage of Passion (1979), was less successful, perhaps because she found it difficult to empathise entirely with her subject.

By now the Countess of Longford had become close to the royal family; her next big biography was to be Elizabeth R (1983), which her friend John Grigg, who did not share her roseate view of the House of Windsor, bluntly told her was “all guff and gush”. In fact, she had slipped into the trap awaiting all royal biographers, of becoming too enamoured of her subject.

Perhaps the only criticism which could be levelled at Elizabeth Longford as a biographer was the outstanding feature of her character – her goodness and generosity of spirit. In a literary world not noted for this, she was almost unique in her encouragement of younger biographers. When I went to interview her for my book on George VI, I confessed my trepidation over my subject. “I’m so glad you are doing it,” she said. I walked away from the Longfords’ Chelsea flat with a newfound confidence. As a successful woman biographer, she was a beacon to my generation.

She carried on writing, into old age, books on the royal family (Darling Loosy: letters to Princess Louise, 1856-1939, 1991; Royal Throne: the future of the monarchy, 1993; Victoria RI, with a new postscript, 1998; and Queen Victoria, for Sutton Pocket Biographies, 1999) – by whom she was rightly appreciated. The Queen Mother is held to have divided women into two categories – the beautiful and stupid, the clever and plain – “except Elizabeth Longford, of course”.

Elizabeth had travelled a strange journey from socialist politics in Stoke to chronicler and proponent of the monarchy, apparently inspired by, of all people, Lytton Strachey. The monarchy appealed to her sense of beauty and history, but this did not embrace its more louche representatives. Her nonconformist background regarded duty as the highest calling, represented in her view by the present Queen and the late Queen Mother. At her 90th birthday she received congratulatory telegrams from, among others, the Queen and Mother Teresa.

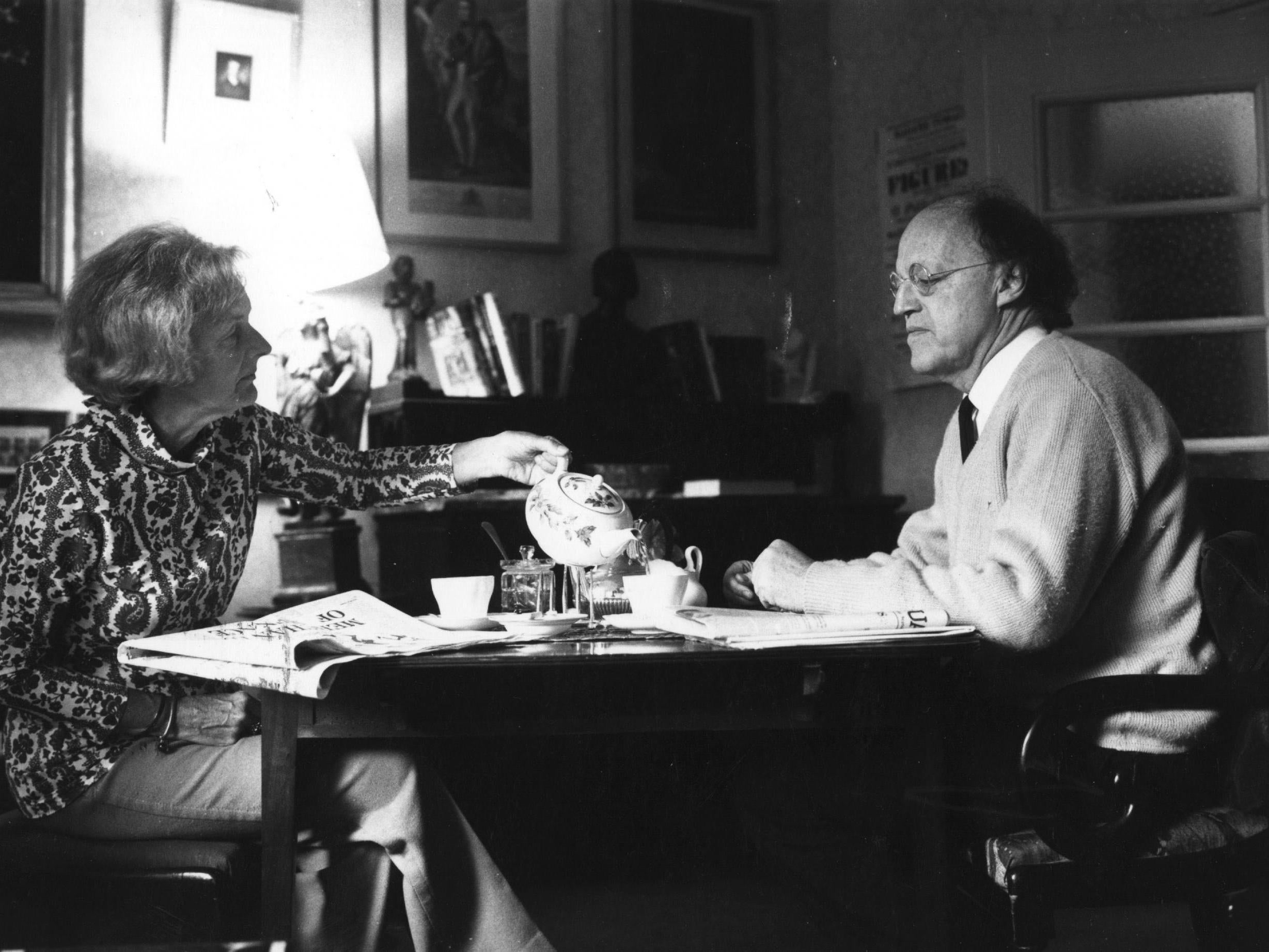

Elizabeth Longford lived a golden life which she richly deserved, as a writer and founder of a writing dynasty (after Antonia and Thomas came Judith Kazantzis, Rachel Billington and Kevin Pakenham, and in the next generation Rebecca and Flora Fraser), as a wife, matriarch and unique personality. There was only one touch of tragedy, the early death of her daughter Catherine, a journalist on the Daily Telegraph Magazine, killed in a car accident at the age of 23, in whose memory the Catherine Pakenham Award for young women journalists was founded. Elizabeth herself died only 14 months after her beloved Frank, as she would have wished.

She once recounted an anecdote of her husband, aged six, at a garden party given by his grandmother Lady Jersey, in honour of Lord Kitchener. “And who are you, my little man?” the heavily moustachioed hero patronisingly asked. Frank Longford put him in his place: “I am the grandson of Grandmama.” Elizabeth Longford’s many descendants felt the same way about her. “When I was a child, we thought of my mother as a goddess,” said her eldest son, Thomas Pakenham. One of her grandchildren, then aged 11, wrote her a Christmas poem:

She is wise and very clever,

Makes mistakes oh! never! never!

We are beauties her and me

Just as women should rightly be,

So brilliant, brainy, driving genes...

Elizabeth Harman, Countess of Longford, writer, born 30 August 1906, died 23 October 2002

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments