A Life in Focus: George Carlin, American standup comedian who always said a word out of place

The Independent revisits the life of a notable figure. This week: George Carlin, from Tuesday, 24 June, 2008

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

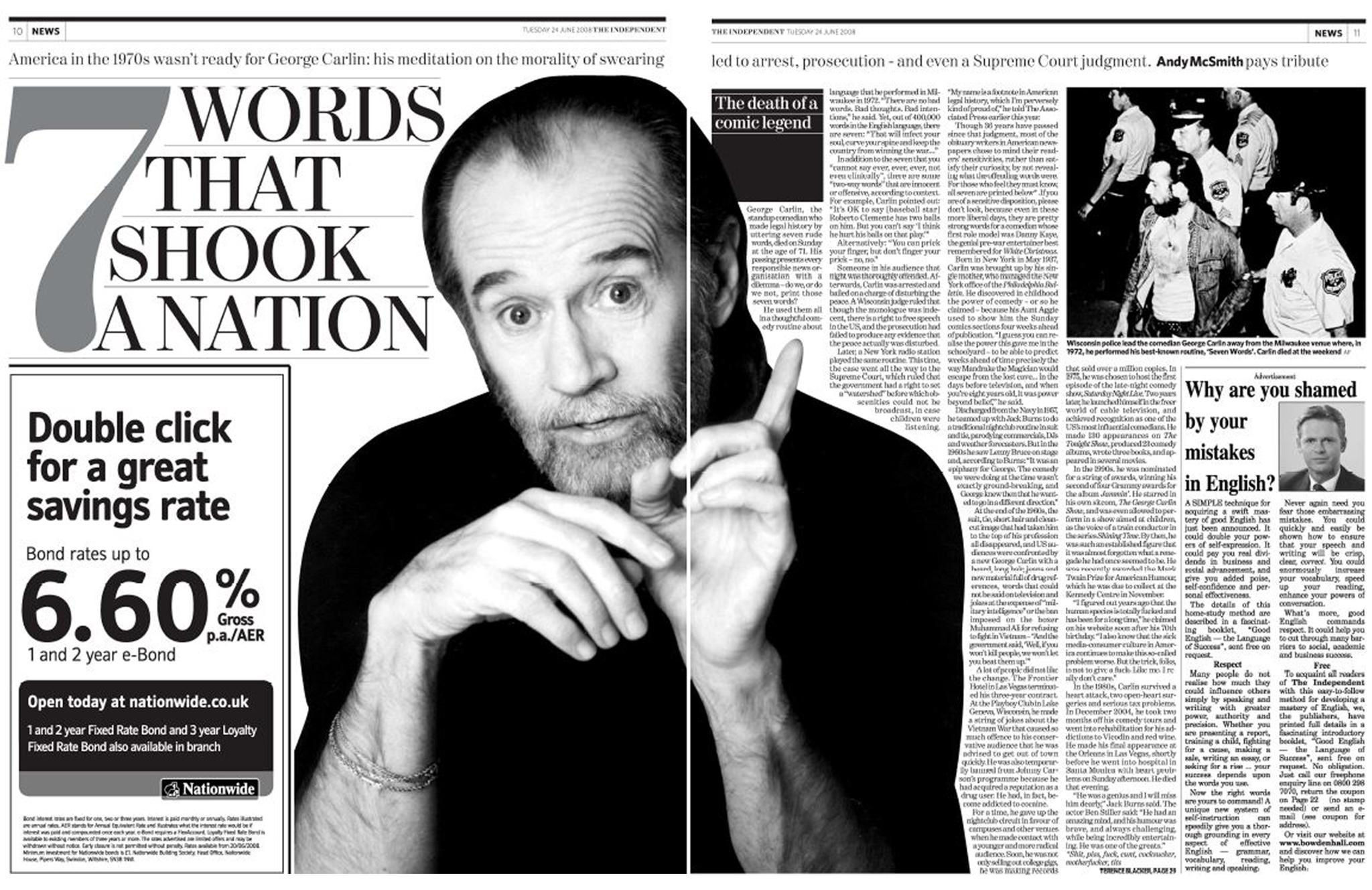

Your support makes all the difference.The legendary standup comedian and advocate of freedom of speech died in 2008. The introduction to the appreciation that appeared in the pages of the newspaper that year, under the title “Seven Years that Shook a Nation”, said: “America in the 1970s wasn’t ready for George Carlin: his mediation on the morality of swearing led to arrest, prosecution and even a Supreme Court judgment.” The article is reproduced in full below.

George Carlin, the standup comedian who made legal history by uttering seven rude words, died on Sunday at the age of 71. His passing presents every responsible news organisation with a dilemma – do we, or do we not, print those seven words?

He used them all in a thoughtful comedy routine about language that he performed in Milwaukee in 1972. “There are no bad words. Bad thoughts. Bad intentions,” he said. Yet, out of 400,000 words in the English language, there are seven: “That will infect your soul, curve your spine and keep the country from winning the war....”

In addition to the seven that you “cannot say ever, ever, ever, not even clinically”, there are some “two-way words” that are innocent or offensive, according to context. For example, Carlin pointed out: “It's OK to say [baseball star] Roberto Clemente has two balls on him. But you can't say 'I think he hurt his balls on that play.'”

Alternatively: “You can prick your finger, but don't finger your prick – no, no.”

Someone in his audience that night was thoroughly offended. Afterwards, Carlin was arrested and bailed on a charge of disturbing the peace. A Wisconsin judge ruled although the monologue was indecent, there is a right to free speech in the US, and the prosecution had failed to produce any evidence that the peace actually was disturbed.

Later, a New York radio station played the same routine. This time, the case went all the way to the US Supreme Court, which ruled that the government had a right to set a “watershed” before which obscenities could not be broadcast, in case children were listening. “My name is a footnote in American legal history, which I'm perversely kind of proud of,” he told The Associated Press earlier this year.

Although 36 years have passed since that judgment, most of the obituary writers in US newspapers chose to mind their readers' sensitivities, rather than satisfy their curiosity, by not revealing what the offending words were. For those who feel they must know, all seven are printed below*. If you are of a sensitive disposition, please do not look, because even in these more liberal days, they are pretty strong words for a comedian whose first role model was Danny Kaye, the genial entertainer best remembered for the 1954 American musical romantic comedy, White Christmas.

Born in New York in May 1937, Carlin was brought up by his single mother, who managed the New York office of the daily evening newspaper, the Philadelphia Bulletin. He discovered in childhood the power of comedy – or so he claimed – because his Aunt Aggie used to show him the Sunday comics sections four weeks ahead of publication. “I guess you can realise the power this gave me in the schoolyard – to be able to predict weeks ahead of time precisely the way Mandrake the Magician would escape from the lost cave ... in the days before television, and when you're eight years old, it was power beyond belief,” he said.

Discharged from the US Navy in 1957, he teamed up with Jack Burns to do a traditional nightclub routine in suit and tie, parodying commercials, DJs and weather forecasters. But in the 1960s he saw Lenny Bruce on stage and, according to Burns: “It was an epiphany for George. The comedy we were doing at the time wasn't exactly groundbreaking, and George knew then that he wanted to go in a different direction.”

At the end of the 1960s, the suit, tie, short hair and clean-cut image that had taken him to the top of his profession all disappeared, and US audiences were confronted by a new George Carlin with a beard, long hair, jeans and new material full of drug references, words that could not be said on television and jokes at the expense of “military intelligence” or the ban imposed on the boxer Muhammad Ali for refusing to fight in Vietnam – “And the government said, 'Well, if you won't kill people, we won't let you beat them up.'”

A lot of people did not like the change. The New Frontier Hotel in Las Vegas terminated his three-year contract. At the Playboy Club in Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, he made a string of jokes about the Vietnam War that caused so much offence to his conservative audience that he was advised to get out of town quickly. He was also temporarily banned from Johnny Carson's TV programme because he had acquired a reputation as a drug user. He had, in fact, become addicted to cocaine.

For a time, he gave up the nightclub circuit in favour of college campuses and other venues when he made contact with a younger and more radical audience. Soon, he was not only selling out college gigs, he was making records that sold more than a million copies. In 1975, he was chosen to host the first episode of the late-night comedy show, Saturday Night Live. Two years later, he launched himself in the freer world of cable television, and achieved recognition as one of the US's most influential comedians. He made 130 appearances on The Tonight Show, produced 23 comedy albums, wrote three books, and appeared in several movies.

In the 1990s, he was nominated for a string of awards, winning his second of four Grammy awards for the album Jammin'. He starred in his own sitcom, The George Carlin Show, and was even allowed to perform in a show aimed at children, as the voice of a train conductor in the series Shining Time. By then, he was such an established figure that it was almost forgotten what a renegade he had once seemed to be. He was recently awarded the Mark Twain Prize for American Humour, which he was due to collect at the Kennedy Centre in November.

“I figured out years ago that the human species is totally fucked and has been for a long time,” he claimed on his website soon after his 70th birthday. “I also know that the sick media-consumer culture in America continues to make this so-called problem worse. But the trick, folks, is not to give a fuck. Like me. I really don't care.”

In the 1980s, Carlin survived a heart attack, two bouts of open-heart surgery and serious tax problems. In December 2004, he took two months away from his comedy tours and went into rehabilitation for his addictions to Vicodin and red wine. He made his final appearance at the Orleans in Las Vegas, shortly before he went into hospital in Santa Monica with heart problems on Sunday afternoon. He died that evening.

“He was a genius and I will miss him dearly,” Jack Burns said. The actor Ben Stiller said: “He had an amazing mind, and his humour was brave, and always challenging, while being incredibly entertaining. He was one of the greats.”

*Shit, piss, fuck, cunt, cocksucker, motherfucker, tits

George Denis Patrick Carlin, standup comedian, born 12 May 1937, died 22 June 2008

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments