Review: Franzen dreams big, and goes deep, with 'Crossroads'

From Jonathan Franzen, the writer regarded by many as America’s pre-eminent novelist, comes the first book in a trilogy titled “The Key to All Mythologies.”

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

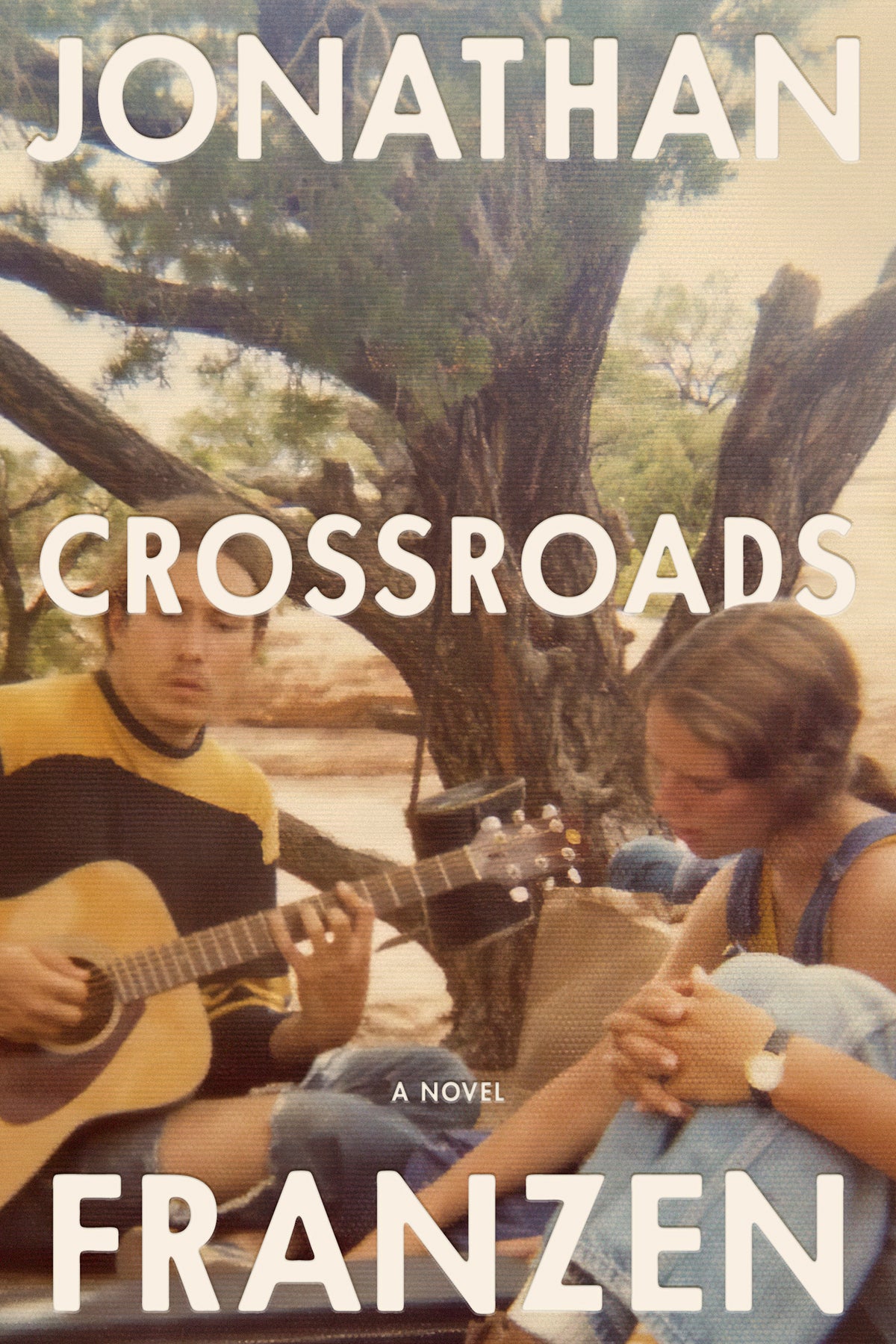

Your support makes all the difference.“Crossroads,” by Jonathan Franzen (Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

Jonathan Franzen dreams big. His newest novel, “Crossroads,” arrives with an audible thud on readers’ doorsteps and will easily hold those doors open at 580 pages. The themes are monumental — from the existence of God to our obligations to family to the morality of war. It’s also the first of a trilogy called, aspirationally, “The Key to All Mythologies.”

But don’t let all the hype surrounding a Franzen novel overwhelm you before reading. In many ways, this is peak Franzen, with richly created characters, conflicts and plot. “Crossroads” introduces readers to the Hildebrandt family at the start of the 1970′s. The patriarch, Russ, is a middle-aged associate pastor at a suburban Chicago church, with less-than-pure thoughts about a widowed parishioner in his congregation and a younger rival in the clergy, Rick Ambrose, whose flourishing youth group gives the novel its name. Russ’ wife, Marion, wonders if all the sacrifices she made to be a pastor’s wife were worth it. And their four kids, from oldest to youngest — Clem, Becky, Perry and Judson — are all caught up in some fashion in the swirling cultural winds of the decade. Despite their religious upbringing, or perhaps in part because of it, there are temptations at every turn, from drugs to pre-marital sex.

And in typical Franzen fashion, we go fathoms deep into all the characters’ heads (except Judson, who at 9, is mostly spared the inner monologue) as they navigate their lives. The introspection is head-spinning at times. Just when a character convinces themselves to do something, they reconsider and the plot spins off in a new direction. That’s not to say any of it feels arbitrary. Franzen has a story to tell, it’s just a story featuring characters who aren’t always sure what they want. The novel’s title is more than just the name of the church’s youth group, after all.

The writing is a marvel. Despite the super omniscient third-person narrator, Franzen also delivers economic lines like these, as we get Marion’s backstory before she met Russ: “Her first Christmas alone wasn’t so bad that it didn’t later seem good.” You feel throughout like you’re in the hands of a very confident storyteller and the joy of the novel is going along for the journey with each character as they make choices and live with the consequences.

You also feel when you finish that the story is just getting started. We’re told on the book jacket that the trilogy will “span three generations,” which means the children will likely be adults in the next volume, and then we’ll approach present day with their children. It’s reminiscent of Updike’s “Rabbit” novels in that regard, except it feels even broader in scope. Russ gets the most pages in novel number one, but it’s truly a family saga. His life choices and the impact they have on the rest of the family will set the stage for what comes in books two and three. And that’s the hard part. An audience accustomed to binge watching will have to wait years for the Hildebrandt story to play out. But isn’t that a moral in many mythologies? Good things come to those who wait.