Israel's first national memorial to war dead avoids addressing country's conflict

The product of decades of political wrangling and emotional strife, Israel’s memorial to its war dead reveals surprisingly little about its current military campaigns

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Israel’s leaders gathered on Wednesday at the country’s new National Memorial Hall for Israel’s Fallen, there was little trace of the long battle it took to build it.

The sombre, annual Memorial Day ceremony took place a day before the celebrations marking the 70th anniversary of Israel’s foundation, according to the Hebrew calendar – and it took nearly that long to create the country’s first national pantheon. Adjacent to the national military cemetery on Mount Herzl in Jerusalem, the Memorial Hall opened to the public without fanfare a few months ago.

The product of decades of political wrangling, emotional strife and procrastination, the monument reveals little about Israel’s wars with its external enemies.

Instead, its minimalist design sidesteps internal conflicts over what should be memorialised, why and how, in a country still fighting its battles and split by deep ideological divisions. Lacking a consensus around a single national narrative, commemoration has been pared down to bare essentials.

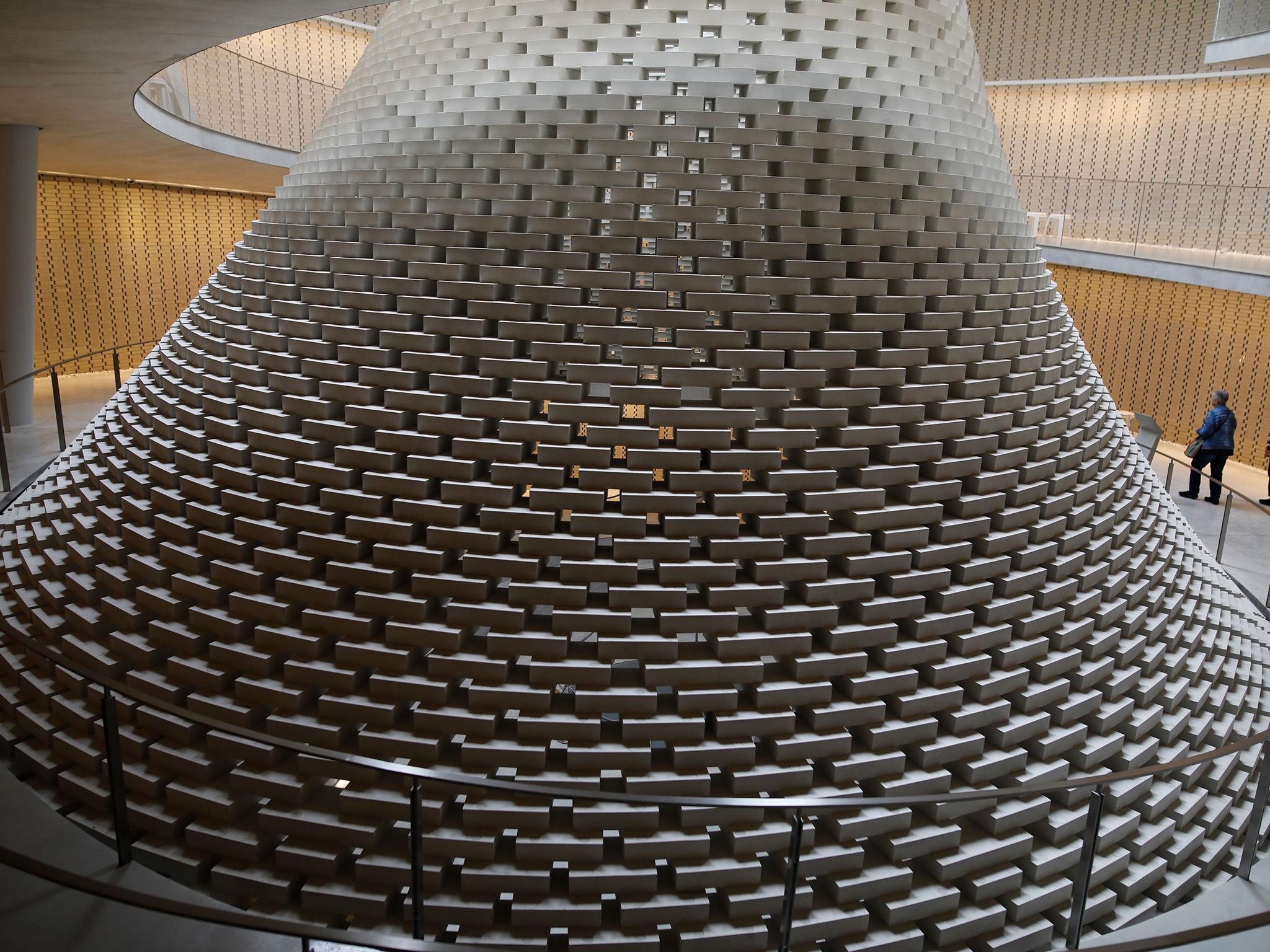

Partly dug into the mountain, the monument consists of a wall of more than 23,600 white bricks, engraved with only the sparest of details: the names of the dead and the dates they died, arranged in chronological order. It spirals around an undulating funnel of light that seems to defy gravity, reaching skywars.

There are no ranks, no mention of the places or circumstances in which the soldiers perished. Using a broad definition of the fallen, it includes not only those killed in action, but also anybody who died in uniform; not only soldiers who fought for Israel, but also those who fought to create Israel.

Avoiding any hierarchy of prestige or loss, privates take their place alongside generals and national heroes. No battles are deemed more or less important than others.

“Once we introduced the concept of unity and equality, it solved all the problems and prevented the arguments,” says Aryeh Muallem, deputy director general of the Israeli Ministry of Defence and head of its Bereaved Families, Commemoration and Heritage department.

Preserving morale is considered critical in a small country where most 18-year-olds are drafted for years of compulsory military service. Last Memorial Day, about 1.5 million Israelis, or roughly one-sixth of the population, visited military cemeteries around the country.

But Israelis cannot even agree on what to call some hostilities, like Israel’s 1982 invasion of Lebanon, which is criticised by many as an unjustified “war of choice”. Officially called Operation Peace for Galilee, it is usually referred to as the First Lebanon War.

Muallem says the memorial was the outcome of a long dialogue with representatives of bereaved families. They presented the state with a challenge, wanting their dead to be remembered individually, on the day they had fallen.

So each inscribed brick has a light beside it, which is illuminated on the personal anniversary. At 11am every day, a brief remembrance ceremony is held for those killed on that date, as their names and images appear on digital screens mounted on 12 pillars. The screens, and a smartphone app, provide more information about the dead.

The wall begins with rows upon rows of blank white bricks, waiting ominously for more names; the design imposes no limit. The first names a visitor sees are the most recent fatalities, and then the wall spirals back to the 1870s, commemorating the earliest casualties of the Zionist struggle and the soldiers of Zionist militias who fought and died before independence.

“We decided to begin from the end, with what most speaks to us today,” says Michal Kimmel-Eshkolot of Kimmel Eshkolot Architects, which designed the monument. The inscribed bricks are no higher than about 6ft from the floor, she says during a tour of the site, “so a mother can reach up and touch the name”.

Etan Kimmel, the chief architect of the project, writes in the brochure that the challenge was to create a space “in a way that touches everyone, but without imposing a uniform interpretation”.

That is at least partly because the issue of war dead stirs painful debate in Israel.

When it was announced last month that Miriam Peretz, who lost two sons in combat and who then dedicated herself to Zionist education, was to be awarded the Israel Prize for lifetime achievement, another bereaved mother, Nomi Miller, criticised the choice as a cynical glorification of suffering.

“We, the mothers, are not worthy of any prize,” she writes in an impassioned Facebook post that elicits thousands of sympathetic reactions. “Our sons’ lives ended forever because our country continues to choose to live by the sword. Fight for peace.”

Before the Memorial Hall, most of Israel’s fallen had been commemorated in museums or monuments established by veterans of particular battles or military corps, or in private memorials scattered around the country. But about 3,000 soldiers were not memorialised anywhere.

The idea for a national monument goes back to 1949, when Israel’s leadership proposed erecting a tomb of the unknown soldier. But the location kept changing, and bereaved relatives had no interest in the idea, arguing that their loved ones were not anonymous, according to Professor Maoz Azaryahu, director of the Herzl Institute for the Study of Zionism at the University of Haifa, Israel.

“When I go back, the whole story of commemoration here in Israel is about names,” Azaryahu says. In the new hall, “metaphorically, the bricks – the names – are the building material of the whole structure”.

Mount Herzl became the focal point of Israeli memory, with its military cemetery and tombs of the founding fathers.

But the idea for a collective monument was quietly dropped until the 1970s, when a plan was developed to build a museum of war and military heritage and a memorial complex on Mount Eitan, outside Jerusalem.

Committees sat. Architects planned. Large amounts of money were invested. Historians, experts and intellectuals filled files with recommendations.

“The new left wanted it to begin in 1948,” says Udi Lebel, a sociology professor at Ariel University in the West Bank and at the Begin-Sadat Centre for Strategic Studies at Bar-Ilan University. “Others wanted it to begin with the Bible and Jericho.”

There were arguments about how to present the consequences of the 1967 war, with some viewing the newly occupied territories as a card for peace negotiations and others as the liberation of Greater Israel. Some wanted the Mount Eitan project to lift morale and encourage service. Others worried about presenting Israel as a militaristic, Sparta-like state.

The debates went on until the 1990s. By then, Israel was signing peace accords with the Palestinians and a treaty with Jordan, and many felt it was not the time to build a war museum.

The push for a memorial resumed in the following decade, finally leading to construction.

“What went up in the end is a place with one function only – to give the names of the fallen,” says Lebel, who specialises in collective memory and the politics of bereavement, adding that even one sentence about how they died could be cause for argument.

“That reflects Israel,” he says. “The only consensus there can be here is empathy for the families and remembering the victims. There is no consensus over the past and we are still living the conflict.”

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments