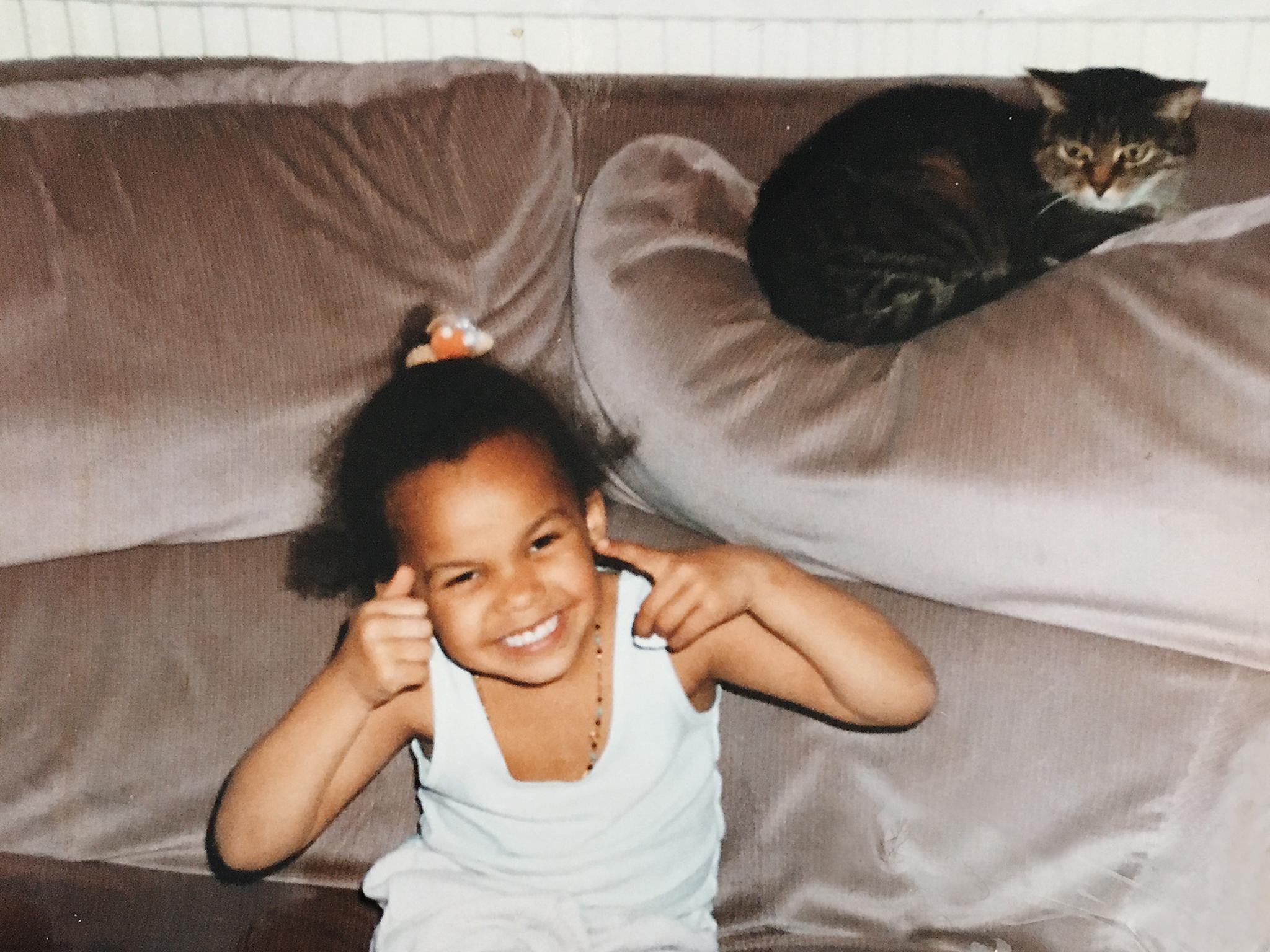

'I was the girl on the missing posters when I was 14 and living with a drug dealer'

Why Sade Banks-Brown thinks the Centrepoint Young and Homeless Helpline could be 'a lifeline'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The pupil referral unit lasted two days: “I rolled a spliff in front the head teacher. He told me to get out. I jumped over the gate and left.”

Two schools had long ago given up on her, the troubled teenager “playing a little game”, of seeing how quickly she could get excluded. (It added up to 80 internal exclusions across two comprehensives.)

Now she was the girl on the missing posters. She walked past them herself occasionally, her photo and the beseeching words: “Have you seen this girl?” She had been missing from family and friends, and any sort of school, for a year.

Sade Banks-Brown had “met a boy”. Who was actually a 20-year-old drug dealer. When she was 14.

It had been fun at first, while the money and the drugs lasted.

“Then the money runs out and you realise you’ve got an addiction, to weed and alcohol.”

He had controlled her, ensured she lost contact with all her friends, and told her “you’ve got nowhere else to go and no-one loves you any more.”

Sade was convinced that if she sought help, revealed herself as the girl on the missing poster, she would be arrested or put into care.

So the drug dealing “boyfriend” got what he wanted: she was effectively his prisoner, all alone in a bedsit in Kilburn, north-west London: mattress on the floor, stolen TV, not much else.

For months on end, she never left the bedsit – except to shoplift food for him. She was to have it cooked and ready for when he got home. With the cleaning done too, down to the gaps between the tiles, with a toothbrush. And if any of his friends came round, well, if she knew what was good for her, she’d lie and say she was 16.

“I had no money. I was completely dependent on him, trapped. He got angry, blamed the whole world for his misfortunes. There were massive rows. You kind of go out of your mind.”

Behind it all, was the “chaotic” upbringing. There’s an undisguised admiration in Sade’s voice as she describes how “an incredible woman” – her mum – fought for her family, did everything she could to make their west London council house a stable, loving home.

But that’s not always easy when you are a single mum with four sons and a daughter, when you’re working up to eight jobs as a cleaner to make ends meet.

And away from the family home and the Christian, boundary-setting mum, there were other influences. She was introduced to drugs, alcohol and an older crowd at a very young age.

From the age of 12, she was regularly running away. By 13, she was getting into fights, robbing people in the street, priding herself on her shoplifting skills. “I was hanging around with older people who did it. It was normal.”

At 14, she met the drug dealer.

Sade, you might think, was the classic hopeless case. She thought so too, once, in Kilburn.

“By the end of the year living with him,” she says, “It got to the point where I was actively trying to kill myself. Not in a deliberate ‘I want to die’ kind of way, but subconsciously. I wasn’t eating, just taking so much drugs and alcohol.

“I was the weight of a child.”

There were two drug-induced comas, the result of taking “a cocktail, of everything.” The second time, in 2006 when she was 15, the hospital somehow found a family contact number. Sade was reunited with her mother, and returned at last to a loving home.

But life doesn’t always provide easy happy endings. With her mum there to support her, Sade was able to renounce her former life and find the courage to go “cold turkey” from the drugs. Despite missing a year of schooling, she even got nine GCSEs.

But when she was 16, the relationship with her mother broke down again as Sade struggled to cope with depression, anxiety and the trauma she had suffered in Kilburn. Like very many other young people, she became homeless through family breakdown.

She also very nearly joined the one in three young people who, according to the charity Centrepoint, are turned away by English councils when they seek help because they are homeless or about to become homeless.

“The woman behind the counter at the housing office,” she recalls, “she said ‘There’s a long waiting list’. I was sat with my friend who was six months’ pregnant, with all she had in two black bin bags. They were telling her the same thing.”

“Essentially,” says Sade, “they want you to be on the point of being on the streets begging, which is one version of homelessness – but there is also the version where your mum doesn’t want you in the house, and you’re vulnerable.

“But you have to sit there until they close the doors and kick you out, and then come back the next morning at 9am when the security guard opens up again.

“And if you can’t do that, you find other means. You spiral downwards. I knew girls who would find a boy, for a house to stay in. In their minds it wasn’t prostitution, it was ‘I kind of like him…’”

Sade didn’t do that. She kept turning up at the housing office, “Nearly every day, for two or three weeks.”

She smiles, acknowledges that she was different from some teenagers: “I was quite determined.”

The local authority put her in a bed and breakfast: “Grim”. Contact with girls who knew boys, in gangs, with guns, forced her to move from hostel to hostel, to another B and B. “It made the first one look like a palace. There were rats, mice, stains on the carpets, on the walls. It stank – of mould, piss and puke.”

She came to Centrepoint when she was 17, but only by accident. She went with a friend who wanted to use the printer at Connexions youth advice centre.

“It’s closed now,” says Sade, pointedly, “because of Government funding cuts.”

“I was sat outside, waiting, bored,” she adds. “This lovely Connexions worker came up to me, asked me if I was OK. She started questioning me about me about my story and then she asked: ‘Have you heard about Centrepoint?' I hadn’t.”

How much better, she muses now, if she had a young and homeless helpline – of the kind now being campaigned for by The Independent – to turn to when she was lonely and despairing in a Kilburn bedsit; to help her with the local authority; to tell her about Centrepoint – and to stop others who lacked her determination from resorting to ‘other means’.

“If there had been a positive voice at the end of a phoneline,” she says, “it would have been a game changer, a lifeline – because if I had succeeded in my self-destruction [in Kilburn], I wouldn’t be here now.”

But here she is, aged 24, smiling, sharply dressed, talking with the charm and poise of the accomplished public speaker she has become.

Centrepoint staff will tell you it is a measure of success if you can meet one of their young people, and have no idea they were ever homeless. In which case, they – and Sade – have done a pretty good job.

All trace of the girl on the missing poster has disappeared – except perhaps, rather fortunately, a certain streetwise wit.

Another day, a different topic, and this would be an interview with a young entrepreneur, the ‘rising talent’ tipped for success.

Sade is now the community engagement manager at London’s Barbican Centre. She is also the founder and CEO of her own charity, Sour Lemons, launched in September, working with the creative industries to improve social mobility among young, low-income Londoners.

You would say it was a miracle, but actually Centrepoint gets a 90 per cent success rate with the young people it helps. Sade ended up staying with Centrepoint for a year, until March 2011. They helped give her the skills to cope with the world of work – after an apprenticeship at the Bush Theatre, she got a job as a producer at the Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith.

And Centrepoint’s “personal development stuff”, says Sade, taught her that actually, she deserved someone who was good to her.

She met another boy, “a really incredible man,” Stephen Brown – a charity worker, not a drug dealer.

They married in October.

And the pupil referral unit? The one where she lasted just two days? The headmaster – that same headmaster – contacted her on her honeymoon. She’s on the board of trustees now.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments