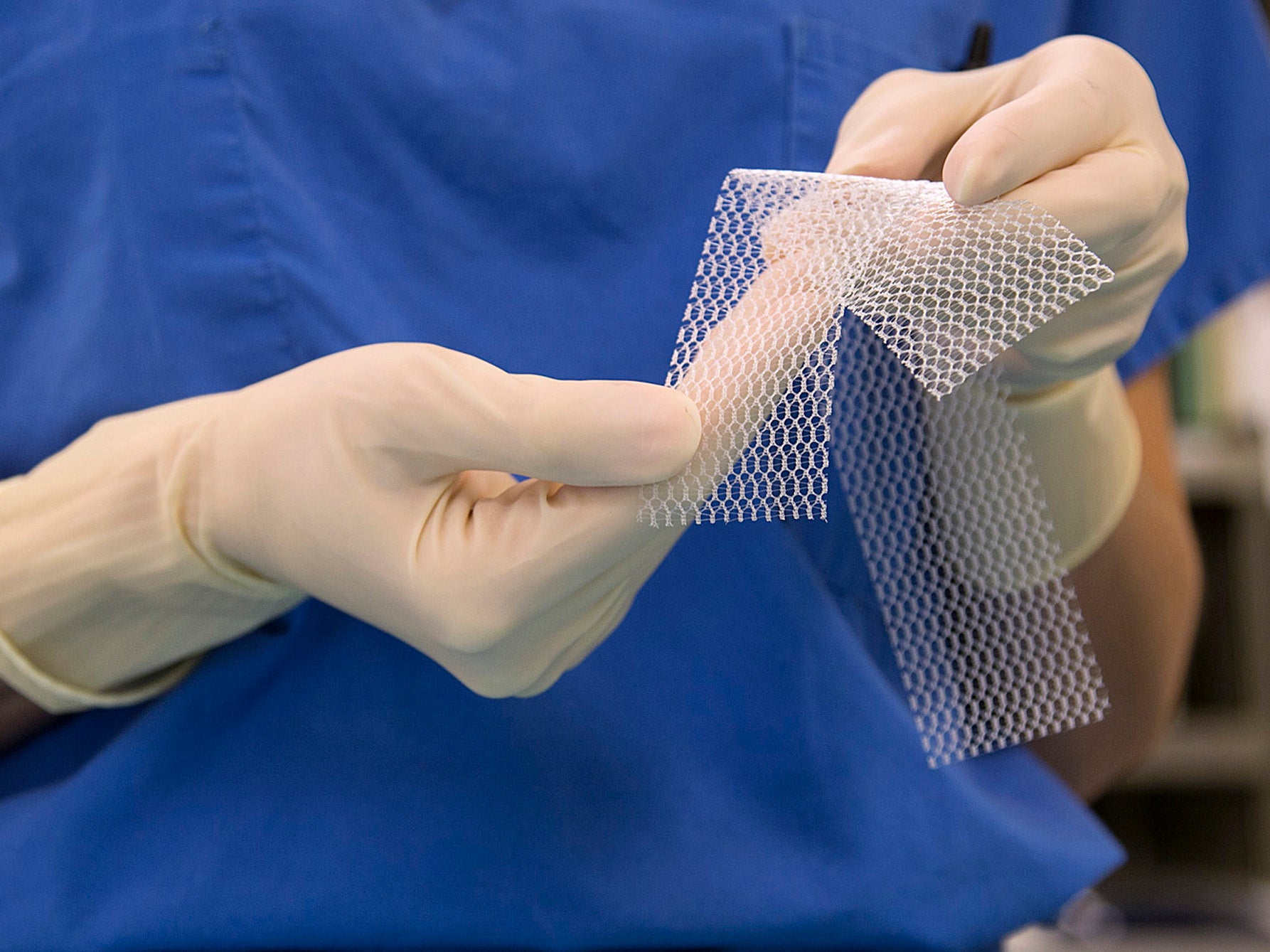

Vaginal mesh: New material which avoids serious injuries and side-effects discovered by scientists

New material is more flexible and could even promote wound healing, but campaigners warn other implants left women with serious internal injuries

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Scientists claim to have created a flexible vaginal mesh implant which will not cause serious injuries of the kind caused by existing rigid models which left women with life-changing injuries.

The unfolding scandal over the use of plastic vaginal mesh implants, which had their approval for use in the NHS withdrawn by watchdogs in December, has led to international legal action and the death of at least one woman.

Now scientists from the University of Sheffield have developed a new form of implant which they said avoids the harmful properties of earlier models while still being able to be surgically useful.

Using polyurethane fibres, a synthetic material used in furniture upholstery, researchers say they have created a material that is flexible and elastic and more closely resembles human tissue.

“This whole area has suffered from a lack of research because the manufacturers denied there was a problem [with the original mesh devices] and patients weren’t listened to,” said Professor Sheila MacNeil, professor of tissue engineering in the department of materials science and engineering at the university.

“Now many millions of dollars have been paid out by mesh manufacturers in compensation, and many have stopped marketing products for this use, because there are so many side-effects.

“But then surgeons look round, there’s no new material to replace it.”

A paper on their new mesh material, published in the Journal of Neurourology and Urodynamics shows it stands up to stress testing better than old models, and performed well in tests in animals.

It is also less likely to cause inflammation when implanted, and can be infused with the hormone oestrogen, which has been shown to promote wound healing.

However it would need extensive testing in clinical trials before it was used in patients.

But mesh campaigners told The Independent that they don’t feel any plastic material should be used for a vaginal implant.

Previous implants were made of the plastic polypropylene, the same material used for plastic bottles, which Professor MacNeil says “lacks the elasticity” of their new mesh and distorts under pressure.

While polypropylene had initially been approved for use in hernia repairs in the stomach, manufacturers were allowed to tweak their design – with no additional testing – and market them for treating a condition called pelvic organ prolapse.

The procedure was commonly offered to women after childbirth, where the pelvic muscles are left weakened and the internal organs can push through into the vaginal cavity.

In the UK, thousands of women are thought to have been fitted with mesh devices for this purpose, with complications reported in one in 10 of them – or as many as a third according to campaigners.

Complications occurred when the mesh shifts, or warps in the body, cutting into the internal wall leading to infections, severe pain and leaving some patients permanently disabled.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) In December, which recommends treatments for use in the NHS, determined before Christmas that the evidence on the use of mesh in organ prolapse was “inadequate” ad it should not be used.

The Government has since said to will review mesh implants given to women in the UK dating back to 2005, to determine the true extent of complications.

Professor MacNeil told The Independent that she was only aware of two other teams working on implant devices for pelvic organ prolapse.

One in the US, working on a mesh made from a natural material, and another in Australia is working on a highly technical solution using the connective tissue, collagen, but these are likely to be more costly.

“I’m delighted other groups are developing these materials, the area needs more research and we ought to be one of twenty groups doing this,” Professor MacNeil added.

But Kath Sansom, founder of the group Sling the Mesh, said the harms caused by one plastic implant should be enough to show that these materials cannot be safely used in such a sensitive area.

“Poly- is key here. Whether it is polypropylene or polyurethane, it is plastic which does not belong in a human body never mind in a woman's vagina which is a clean, uncontaminated field.

“Plastic is not inert which means it can change once implanted. It can shrink, twist degrade and it is that which is catastrophic once inside women’s bodies.”

Previous mesh implants have been shown to break down inside patients, with microplastic particles passing into the body.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments