The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

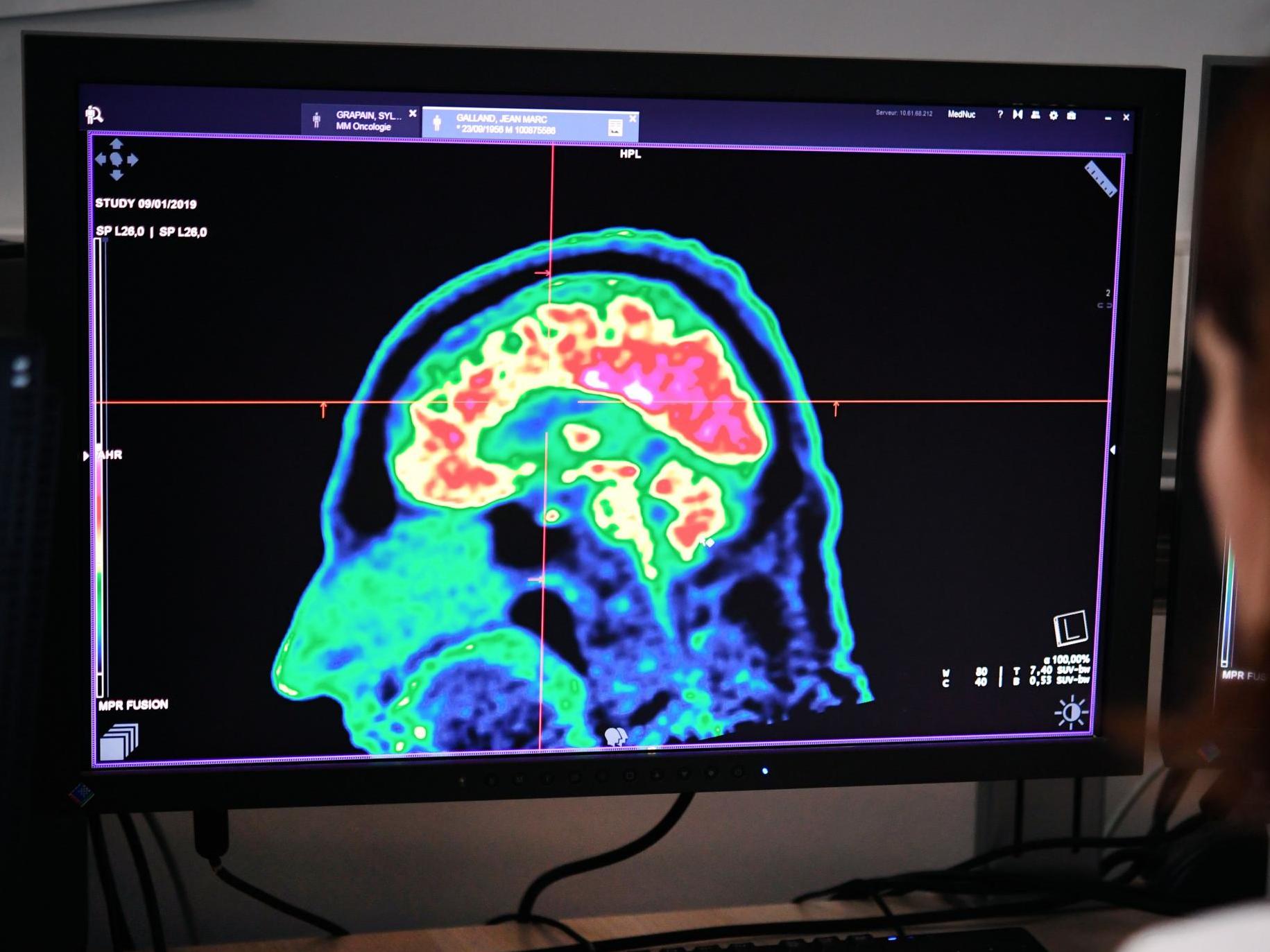

Previously 'untreatable' childhood brain cancer could be beaten with new type of drug

No new drugs have been licensed to treat brain cancer in adults or children for 20 years

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A new drug could be used to target previously “untreatable” childhood brain cancer, scientists have said.

The drug could also help patients who suffer from the rare but deadly inherited disease “stone man syndrome“, in which their muscles and ligaments turn to bone.

The study, led by the Institute of Cancer Research (ICR) in London, found the new drug can shrink tumours in mice and kill brain cells with mutations in the ACVR1 gene found in the deadly childhood brain cancer diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG).

DIPG cannot be removed by surgery as the tumours occur in the brainstem and chemotherapy does not work. Radiotherapy is typically used to extend the life of the child.

The research was funded in part by Abbie’s Army, a charity set up by Amanda and Ray Mifsud after they lost their daughter Abbie to DIPG brain cancer in 2011 when she was six years old.

Children with DIPG are typically expected to live only nine to 12 months after their diagnosis.

No new drugs have been licensed to treat brain cancer in adults or children for 20 years.

Researchers at the ICR discovered ACVR1 mutations occur in a quarter of DIPG tumours in 2014, and began to create a new series of molecules that target the mutations.

The ICR-led team tested 11 prototype drugs with anti-ACVR1 activity on brain cancer cells grown in the lab, and found two of the prototypes were particularly good at blocking ACVR1 signals and killing ACVR1-mutant cells, while having little effect on healthy brain cells.

They transplanted human DIPG tumours into mice and found the potential new drugs stopped ACVR1 activity, shrunk tumours and extended survival by 25 per cent (from 67 to 82 days).

Looking at cells in the lab, the new study found ACVR1-mutant cells respond inappropriately to a molecule called activin A, which is present in high levels during brain development, sparking a cascade of events that trigger tumour growth.

A similar situation is thought to occur in stone man syndrome, with high levels of activin A occurring during inflammation in muscles and inappropriately triggering the formation of bone tissue in people born with ACVR1 mutations.

Clinical trials of ACVR1 inhibitor drugs on children with brain cancer are expected to begin in 2021, conducted by open science company M4K (Medicines for Kids) Pharma.

“It’s simply not good enough that we can cure some cancers, but in others we have seen no progress in decades,” said professor Chris Jones, a researcher at the ICR. “We owe it to children and their families to do better.”

The study was funded by Abbie’s Army, Children with Cancer UK, Cancer Research UK and the DIPG collaborative and was published in the journal Communications Biology.

Additional reporting by SWNS

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments