Shrewsbury maternity scandal: Families recall deaths and injuries of babies being ‘brushed under the carpet’

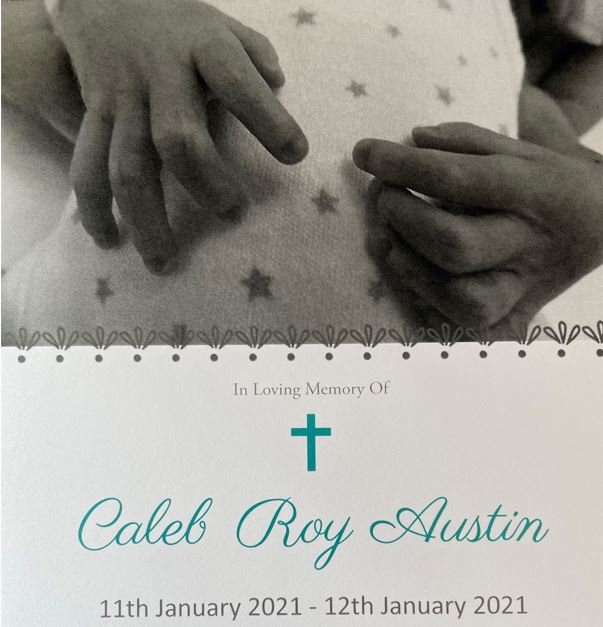

‘When something isn’t right, just listen to the parents,’ says Nikhita Hose, whose son Caleb died in January 2021

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.On Wednesday, a watershed moment for maternity safety will take place as the final report of the inquiry into the largest maternity scandal ever seen within the NHS is set to reveal failings in the care of hundreds of women and babies.

The damning report, led by senior midwife Donna Ockenden and published on Wednesday, examined cases involving 1,486 families between 2000 and 2019, and reviewed 1,592 clinical incidents.

It found Shrewsbury and Telford Hospital NHS Trust presided over catastrophic failings for 20 years - and did not learn from its own inadequate investigations - which led to babies being stillborn, dying shortly after birth or being left severely brain damaged.

It came after The Independent revealed in 2019 an inquiry into maternity care at Shrewsbury and Telford Hospital NHS Trust had found that more than a dozen women and more than 40 babies had died during childbirth because of a culture that failed to listen to parents.

The stories uncovered by the review, spanning 40 years, point to repeated failings across a hospital that, in the words of the families affected, “did not listen”.

However, parents and children continue to be subjected to similar failings – like those experienced by Nikita Hose.

‘Just listen’

Ms Hose lost her son Caleb in January 2021 at Shrewsbury and Telford Hospital, and is being represented by law firm Lanyon Bowdler.

Caleb’s death was not covered by the Ockenden inquiry, as his birth occurred after the interim report was published in December 2020, but the failings in his care reveal similar problems to those previously identified.

Ms Hose was admitted to hospital on 8 January after doctors confirmed her waters had broken at 27+1 weeks. She had previously found out she was pregnant at 20 weeks, after experiencing a “gush of fluid” that was not investigated.

On 10 January 2021 she raised concerns with doctors after developing a fever and suffering from blurred vision, but was told to just take her pyjama bottoms off. Speaking to The Independent, Ms Hose said: “I felt like they weren’t really listening to me ... I did mention I didn’t feel [Caleb] moving a few times.”

After being told she needed a C-section, Ms Hose was left waiting for surgery for hours, and by the time Caleb was born he was very unwell. Tragically, one day later he died.

The trust held its own investigation into Caleb’s death, which found that, had he been born eight hours earlier as he should have been, he would have survived.

Ms Hose told the trust she now wants it to “just listen. When something isn’t right, just listen to the parents. Just listen to the parents and don’t blame the parents. A mother knows their body and a mother knows when something’s not right.

“Caleb was born a month after Donna Ockenden’s interim report [which] said that things needed to change straight away, and five or six things that were on Donna Ockenden’s interim report were on Caleb’s serious incident report.

“I still cry about it now, nearly every day. It’s something that you’ll never ever get over – ever. No matter how much counselling, medication, [nothing] will get you over what’s happened because there’s no words for it. There are just no words.”

Laura Weir, an associate at Lanyon Bowdler, the solicitors representing the families, said: “Unfortunately we continue to see the same failings at the trust, and change is still needed to ensure our community has access to safe maternity care.

“We will continue to seek justice for the families affected, and I hope that Donna Ockenden’s final report gives the trust the framework they need to implement real change.”

‘I had to fight’

It took 20 years for Jill Edwards to find out about the mistakes made during her labour that led to her daughter, Kirsty Dallows, being left with cerebral palsy.

In 1983, when she was ten days overdue, Ms Edwards was admitted to hospital, and from then on a series of errors would occur that would leave her and her daughter living with the consequences forever.

After trying forceps initially, Ms Edwards’ doctors said she would need a caesarean. “As far as I was aware that was it,” said Ms Edwards. It was only during court hearings years later that she found out that doctors had in fact made a further attempt at a vaginal delivery with forceps while she was under general anaesthetic.

The two attempts at using forceps, coupled with attempts to dislodge the infant from her pelvis, left Ms Edwards’ daughter in foetal shock and suffering from a cerebral haemorrhage.

Ms Edwards recalls seeing her daughter days later: “She was lying on her side, her head as far back as it could go, her arms sticking out just towards the little portal and her legs crossed. Basically she looked like she was waterskiing but with her head far back.”

She was told by doctors at the time that she did not have to take her daughter, and that there were places for babies like her, but Ms Edwards refused to give her up. Nine months later, Kirsty was diagnosed with cerebral palsy.

In the years that followed, Ms Edwards had to fight for answers through legal routes.

“I had to fight them so hard, because they said they lost all of her birth notes,” she said. “It was never about money for me, it was just to find out what had gone on. I’d always blamed myself and I was always led to believe that [it was] something to do with me.

“The minute I walked into that hospital, that was her life over. Sadly there are babies that died, [and it] feels really difficult, because you feel guilty because your baby didn’t die, but at the same time I was still living with the terrible things that had happened.”

‘She died in my arms’

“She died in my arms; I don’t remember that,” Julie Rowlings told The Independent as she described the horrific circumstances of her daughter Olivia’s death.

Olivia was born on 14 May 2002 in Shrewsbury hospital.

After 23 hours of labour, the consultant in charge decided to use forceps on Ms Rowlings.

“He went in twice with forceps. My husband had me under the arms and was holding me up because I was being pulled down the table. He could see one of his feet was off the floor and on the base of the table [as he was] pulling,” she said.

Unbeknown to Ms Rowlings, her daughter would be left with horrendous injuries from the forceps.

When Olivia was born “there was not a sound”, recalled her mother. After her daughter was taken to the special care unit, Ms Rowlings found her in a shocking state.

Her “ear was all cut, like it was almost severed, and she had a big blue bruise on the top of her head and across her face”, she said.

Even after being told her baby had died, like so many other women, Ms Rowlings had to endure being placed on a ward full of other women with their babies. “I was distraught and they told us to keep the noise down,” she said.

It took four years for the trust to admit liability, and eventually Olivia’s death was investigated by the police.

During legal proceedings it was found that Olivia had been left with a “haematoma the full size of her scalp, that was 2.5cm thick, reaching across her face, and her brain stem was almost severed. Every major organ had haemorrhaged, and the acid levels in her blood were through the roof, which means that she was having a lot of pain.

“I don’t want any family to ever have to live with the heartbreak, because it never gets easier. You learn to live with it a little easier, but it never goes away.”

‘Brushed under the carpet’

Heidi Mortimer, from Telford, lost her son Harrison in April 2004 after he was deprived of oxygen as a result of pre-eclampsia.

In the weeks prior to her son’s death, Ms Mortimer began to “swell like a balloon” and was initially told by staff at Shrewsbury and Telford Hospital that everything was “fine” and there was “nothing to worry about”.

However, after her swelling worsened, she attended hospital again and was admitted at 23 weeks pregnant.

She described being told during the first two weeks of her stay in hospital: “Baby’s fine. Baby’s very happy inside you. We want to keep baby inside you as long as we can.”

Eventually doctors told her she had pre-eclampsia, and days later, after she returned from a day trip out of hospital with her family, midwives said they could not find her son’s heartbeat.

Doctors told her that her son had died, and she was sent into a room on the hospital’s labour ward.

“I could hear all the women screaming, you could hear babies crying. And I’m sat there with a bump, knowing that he’s never going to cry,” said Ms Mortimer. “You could hear women, you could hear babies crying, cots were out, incubators were there ready and waiting for babies. And I was just like, ‘This is just a bad dream,’” she said.

After giving birth to her son, complications meant that Ms Mortimer had to go through contractions again to deliver her placenta. At one point, she said, “A doctor came to examine me and literally put his fist up there and tried to rip my placenta out. I was hanging off the ceiling [in pain]. I was just like, ‘Please stop, please stop now.’ He said, ‘No, this needs to come out. It needs to come out.’

“And I said, ‘Please stop. You’re hurting me. I’ve been through enough, stop,’ and he wouldn’t stop, he carried on. And I could feel every movement.”

It was only when the midwife asked the consultant to stop that he desisted, Ms Mortimer said.

In the weeks following her son’s death a postmortem was carried out, which doctors said pointed to a lack of oxygen.

Despite being previously told her placenta was “welded to her womb” and “disintegrated like paper”, Ms Mortimer felt her care was “brushed under the carpet”, adding that it was “never mentioned again”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments