Doctors' inconsistent meningitis advice putting children at risk, charity warns

Report details stories of 134 parents whose children had bacterial meningitis. Three-quarters were given inappropriate reassurances and in 23 cases children died

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Up to half of children with bacterial meningitis are not diagnosed when they first see a doctor and charities are warning parents are too often sent home without advice to go straight to hospital if symptoms get worse.

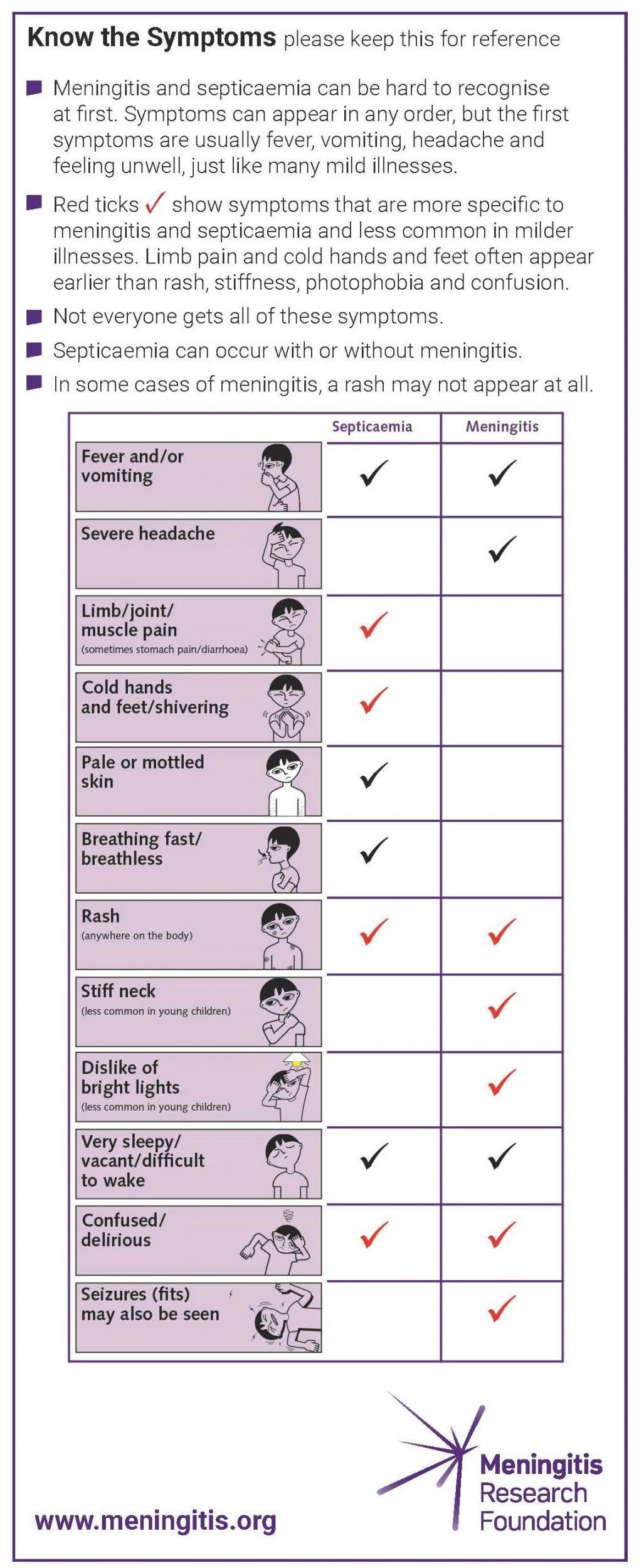

Recognising the early signs of meningitis can be extremely difficult as they are often similar to a cold flu or ear infection, however the infection can turn deadly within 24 hours, the Meningitis Research Foundation said.

For this reason national guidelines state GPs and A&E staff should give “safety netting” advice to parents on how long a minor illness should last and what to do if symptoms worsen, whenever they see a child with a non-specific infection.

But a report by the charity has warned that too often safety netting isn’t happening, and patients are given misplaced reassurances that actually delay seeking appropriate help.

The report includes accounts from 134 parents, 103 of which were sent home with inappropriate reassurances that it was a milder condition.

In 23 of the cases the child had died, while others suffered serious injuries such as amputations or brain damage.

Kirstie Walkden’s nine-month-old daughter, Amy, became critically ill in August last year after a few days feeling “out of sorts”.

“I took her to A&E on the Sunday when her symptoms escalated; temperature, vomiting, mottled skin, fast breathing, lethargic,” Ms Walkden said. “However, we were sent home with antibiotics for a suspected ear infection. I was surprised but felt reassured.”

“Back at home her temperature continued to soar and by the Tuesday she was no longer eating or drinking and I couldn’t get any normal response from her.

“My instincts were screaming this was serious so I made the decision to take her back to hospital – where all hell broke loose.”

Within an hour the hospital was treating her for meningitis and sepsis, a complication from severe infections where the immune system goes into overdrive and starts attacking the body.

“We were living a nightmare and pleading for her to keep on fighting, and on day 18 she was finally well enough to come home,” Ms Walkden said. While Amy is recovering well, she added “only time will tell” if there were long-term effects from the infection.

Research in the foundation’s report shows 49 per cent of children with meningococcal infection, the most common cause of bacterial meningitis, are sent home after their first check with a GP or other health professional, and not sent to hospital.

Other studies say a third of patients are sent home or given inappropriate reassurances and the charity warns safety netting information given by doctors is often highly variable, and may not cover both meningitis and sepsis symptoms.

There is also no system to monitor or evaluate the advice given to assess how many parents receive the appropriate instructions and this needs to change, the charity said.

Vinny Smith, chief executive of Meningitis Research Foundation said: “There’s a real risk that doctors can easily miss meningitis and sepsis in the early stages.

“Offering patients or parents of children safety netting information could be life saving if a child with a serious illness is sent home.

“Parents often have a gut instinct and know when their child is seriously ill. When a child is ill and getting rapidly worse, parents should not be afraid to seek urgent medical help – even if they’ve already been seen by a doctor that same day.”

Chair of the Royal College of GPs Professor Helen Stokes-Lampard said: “GPs are on permanent alert for signs of meningitis in their patients and we do speak to the parents of babies and young children about what they need to look out for.

“GPs also recognise that parents and carers are the ones who really know their child best and that listening to a parents’ concerns about their child is often an important indicator of whether something is not right.”

She said resources to standardise information given to parents on what to look out for would be welcome.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments