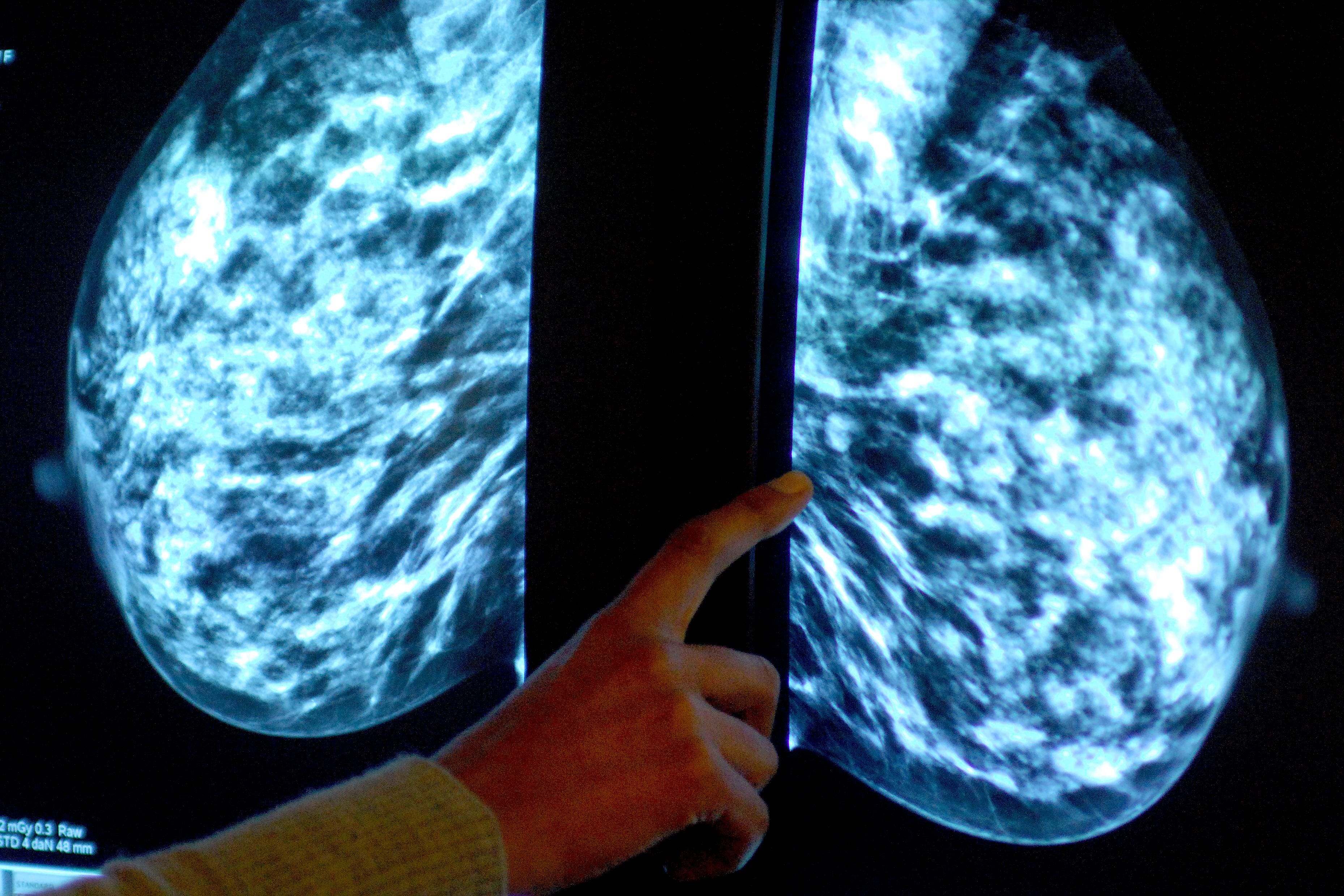

New model could offer personalised breast cancer screening approach, say experts

Researchers say their study could help to potentially reduce breast cancer deaths, and cut unnecessary screenings for those at lower risk.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Researchers have developed a new model that predicts a woman’s likelihood of developing and then dying of breast cancer within a decade.

Current breast cancer screening is vital, but can lead to overdiagnosis and unnecessary treatments, posing challenges to the NHS, researchers say.

They suggest the new model could aid a personalised screening approach, targeting women at the highest risk.

This could potentially reduce breast cancer deaths, and cut unnecessary screenings for those at lower risk.

Risk-based strategies could offer a better balance of benefits and harms in breast cancer screening, enabling more personalised information for women to help improve decision making

Julia Hippisley-Cox, professor of general practice and epidemiology and senior author from the Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences at the University of Oxford, said: “This is an important new study which potentially offers a new approach to screening.

“Risk-based strategies could offer a better balance of benefits and harms in breast cancer screening, enabling more personalised information for women to help improve decision making.

“Risk-based approaches can also help make more efficient use of health service resources by targeting interventions to those most likely to benefit.

“We thank the many thousands of GPs who have contributed anonymised data to the QResearch database, without which this research would not have been possible.”

The study published in Lancet Digital Health analysed data from 11.6 million women aged 20 to 90 from 2000 to 2020.

None of the women had a prior history of breast cancer, or the precancerous condition called ‘ductal carcinoma in situ’ (DCIS).

Researchers say breast cancer screening is vital but has challenges.

It reduces breast cancer deaths, but can sometimes detect tumours that are not harmful (overdiagnosis), which leads to unnecessary treatments.

This not only harms some women, but is also causes unnecessary costs to the NHS.

Data suggests that for every 10,000 UK women aged 50 years invited to breast screening for the next 20 years, 43 breast cancer deaths are prevented by screening, but 129 women will be overdiagnosed.

With risk-based screening, the aim is to personalise screening depending on an individual’s risk, to maximise the benefits and minimise the downsides of such screening.

Tailoring screening programmes on the basis of individual risks was recently highlighted as an avenue for further improvement in screening strategy by Professor Chris Whitty.

Funded by Cancer Research UK and taking advantage of the size and richness of the QResearch database ... we were able to explore different approaches to develop a tool that might be helpful for new, risk-based public health strategies

Currently, most models of risk work by estimating the risk of a breast cancer diagnosis.

But researchers say not all breast cancers are fatal, and it is known that the risk of being diagnosed does not always align well with the risk of dying from breast cancer after diagnosis.

The new model works to predict a woman’s 10-year combined risk of developing and then dying from breast cancer.

Identifying those at the highest risk of deadly cancers could improve screening.

These women could be invited to start screening earlier, be invited for more frequent screenings, or be screened with different types of imaging, experts suggest.

Is it thought a personalised approach could further lower breast cancer deaths while avoiding unnecessary screening for lower-risk women.

And women at higher risk for developing a deadly cancer could also be considered for treatments that try to prevent breast cancers developing.

Researchers tested two more traditional statistical-based models, as well as two used machine-learning (a form of artificial intelligence) models.

If further studies confirm the accuracy of this new model, it could be used to identify women at high risk of deadly breast cancers who may benefit from improved screening and preventative treatments

They all included the same types of data, including a woman’s age, weight, history of smoking, family history of breast cancer, and use of hormone therapy (HRT).

The models were evaluated for their ability to predict risk accurately overall, and across a diverse range of groups of women, such as from different ethnic backgrounds and age groups.

The study found that one statistical model, developed using competing risks regression performed the best overall.

It most accurately predicted which women would develop and die from breast cancer within 10 years.

The machine-learning models were less accurate, especially for different ethnic groups of women, the research found.

Dr Ashley Kieran Clift, first author and clinical research fellow at the Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford, said: “Funded by Cancer Research UK and taking advantage of the size and richness of the QResearch database with its linked data sources at the University of Oxford, we were able to explore different approaches to develop a tool that might be helpful for new, risk-based public health strategies.

“If further studies confirm the accuracy of this new model, it could be used to identify women at high risk of deadly breast cancers who may benefit from improved screening and preventative treatments.”