How difficulty in identifying emotions could be affecting your weight

Comfort eating stems from difficulty in recognising how you're feeling, researchers at Swansea University find

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Most of us have turned to food to make ourselves feel better at some point. Whether it is snuggling up with a pot of ice cream following a break-up (channelling an inner Bridget Jones perhaps) or turning to chocolate and biscuits to keep us going through a difficult day at work. This is known as emotional eating, consuming food in response to emotions. But while it may make us feel better initially, in the long run it can have a negative impact on our health.

We are all aware that obesity is a major societal issue with rates still increasing. Overeating in response to emotions is just one of the many factors thought to drive weight gain and increase body mass index (BMI). However, while other factors do come into play, it is important to understand how emotions may influence weight gain to help aid weight loss and management.

So, why do we turn to food when we’re feeling emotional? Some researchers argue that emotional eating is a strategy used when we are unable to effectively regulate our emotions. This “emotional dysregulation” can be broken down into three aspects – understanding emotions, regulating emotions, and behaviours (what we do in response to a given situation).

Understanding our emotions involves being able to identify them and describe them to others. Being unable to do this is part of a personality trait called alexithymia, which literally means having “no words for emotions”. Varying degrees of alexithymia occur from person to person. Around 13 per cent of the population could be classed as alexithymic, with the rest of us falling somewhere along a continuum.

Emotional regulation, meanwhile, encompasses the strategies we use to reduce (negative emotions) and manage our emotions generally. It can include exercising, breathing or meditation, as well as eating.

A number of things influence how we regulate emotions. This includes personality factors such as negative affect (general levels of depression and anxiety) and negative urgency (acting rashly in response to negative emotions). When experiencing upsetting emotions, impulsive people may act without thinking.

For example, when feeling upset during an argument with a loved one, you may say something in the spur of the moment which you later regret. If a person cannot appropriately regulate their emotions, it can lead to the use of ineffective strategies, such as emotional eating.

Effects on BMI

To date, the links between emotional dysregulation, emotional eating and BMI/weight gain have not really been understood. But in our latest research, we propose a new model of emotional eating, and in turn, BMI.

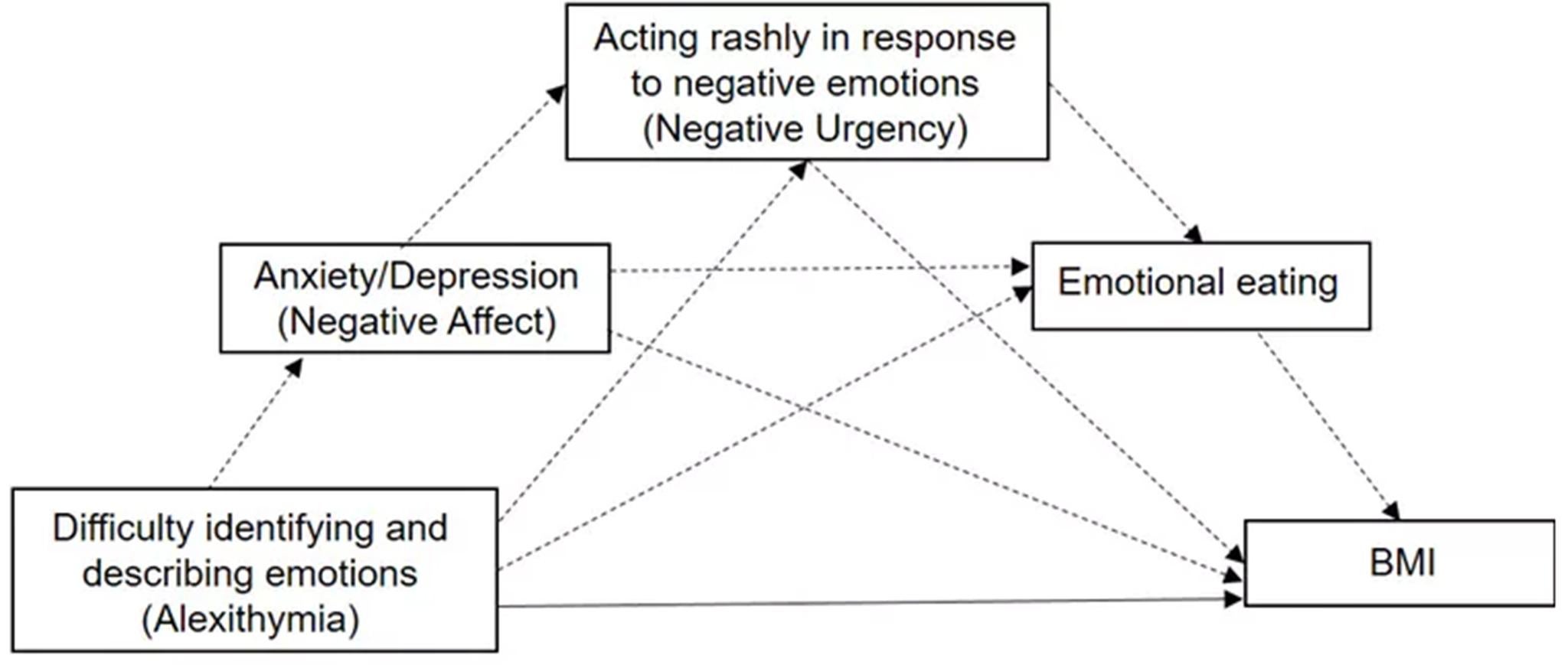

For the study we used difficulty understanding emotions (alexithymia) as a way of characterising emotional dysregulation. As can be seen in the figure below, we propose that alexithymia, negative affect (general levels of depression and anxiety), negative urgency (acting rashly in response to negative emotions), and emotional eating may all play a role in increasing BMI.

We tested this model in a student sample (aged 18 to 36) as well as a more representative sample (18-64). Within the student sample, we found a direct link (where one factor, “X”, directly influences another, “Y”) between difficulty identifying emotions and increased BMI. Independent of other factors, individuals who were unable to identify their own emotions generally had a higher BMI.

We also found that difficulty identifying emotions indirectly (X influences Y but via one or more additional factors) predicted BMI via depression, negative urgency (rash emotional responses) and emotional eating in the student sample. And that difficulty describing emotions indirectly predicted BMI via anxiety alone, as well as via anxiety, negative urgency and emotional eating. In other words, being unable to identify and describe emotions increases vulnerability to depression and anxiety respectively.

In turn, this depression and anxiety increases the likelihood of a person reacting without thinking. This means they are more likely to turn to food to alleviate their negative feelings, experiencing increased weight and BMI as a result.

In the more representative sample only indirect links between difficulty identifying emotions and increased BMI were found. But here depression and negative urgency play a stronger role. Specifically, difficulty identifying emotions was indirectly linked to BMI via an increased tendency to experience depression alone. Meanwhile, difficulty describing emotions via an increased tendency to act rashly in response to negative emotions was linked to BMI when anxiety was included in the model.

While the precise mechanism by which emotions drive emotional eating and its impact on BMI remains unclear, our study is the first step in developing a model of BMI that is inclusive of multiple factors. Because emotional eating is a coping strategy for emotions, it’s important to consider how emotional regulation relates to weight loss and management programmes.

For example, improving the ability to identify and describe emotions may reduce a person’s tendency to turn to food, which can lead to positive effects on their health.

Aimee Pink is a research officer at Swansea University, Claire Williams is a senior lecturer in psychology at Swansea University, Menna Price is a lecturer in psychology at Swansea university and Michelle Lee is a professor of psychology at Swansea University. This article first appeared on The Conversation.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments