Detox products have been around, and criticised, for centuries

Teas and powders that promise miraculous health and wellness benefits have been on the market since the 19th century, and they have been both enormously popular and controversial

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

If you use social media platforms such as Instagram, there’s a good chance you’ve seen accounts promoting diet pills and teas. These products often claim to be “detoxifying”, as well as promising weight loss and increased energy.

The promotion of these products has been so pronounced in recent years that the medical director of the NHS, Stephen Powis, has argued that social media platforms should take down posts that promote these products due to their “damaging impact on physical and mental health”. And in recent weeks, Instagram announced it will be removing all posts that make “miraculous” claims about diet or weight loss products.

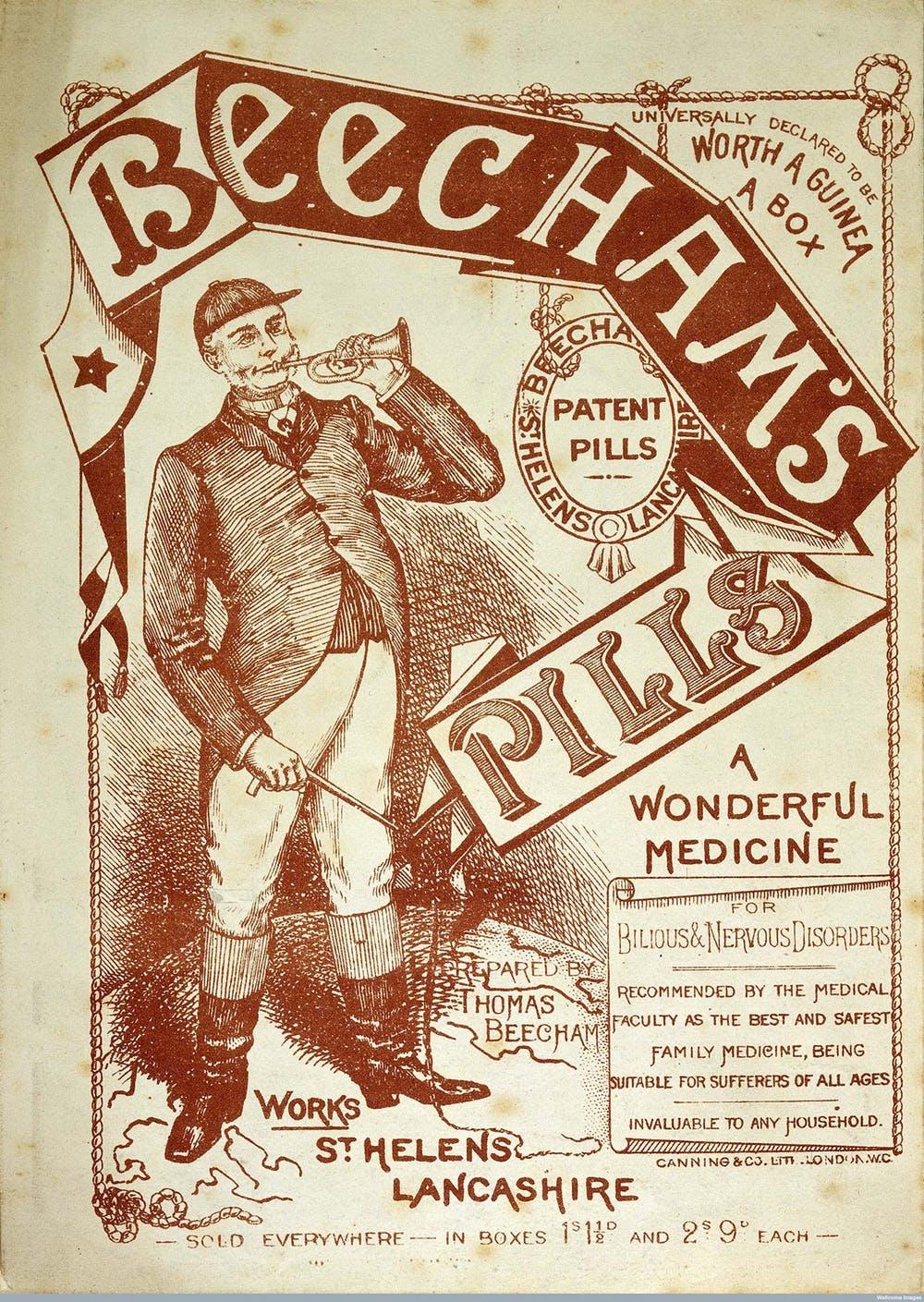

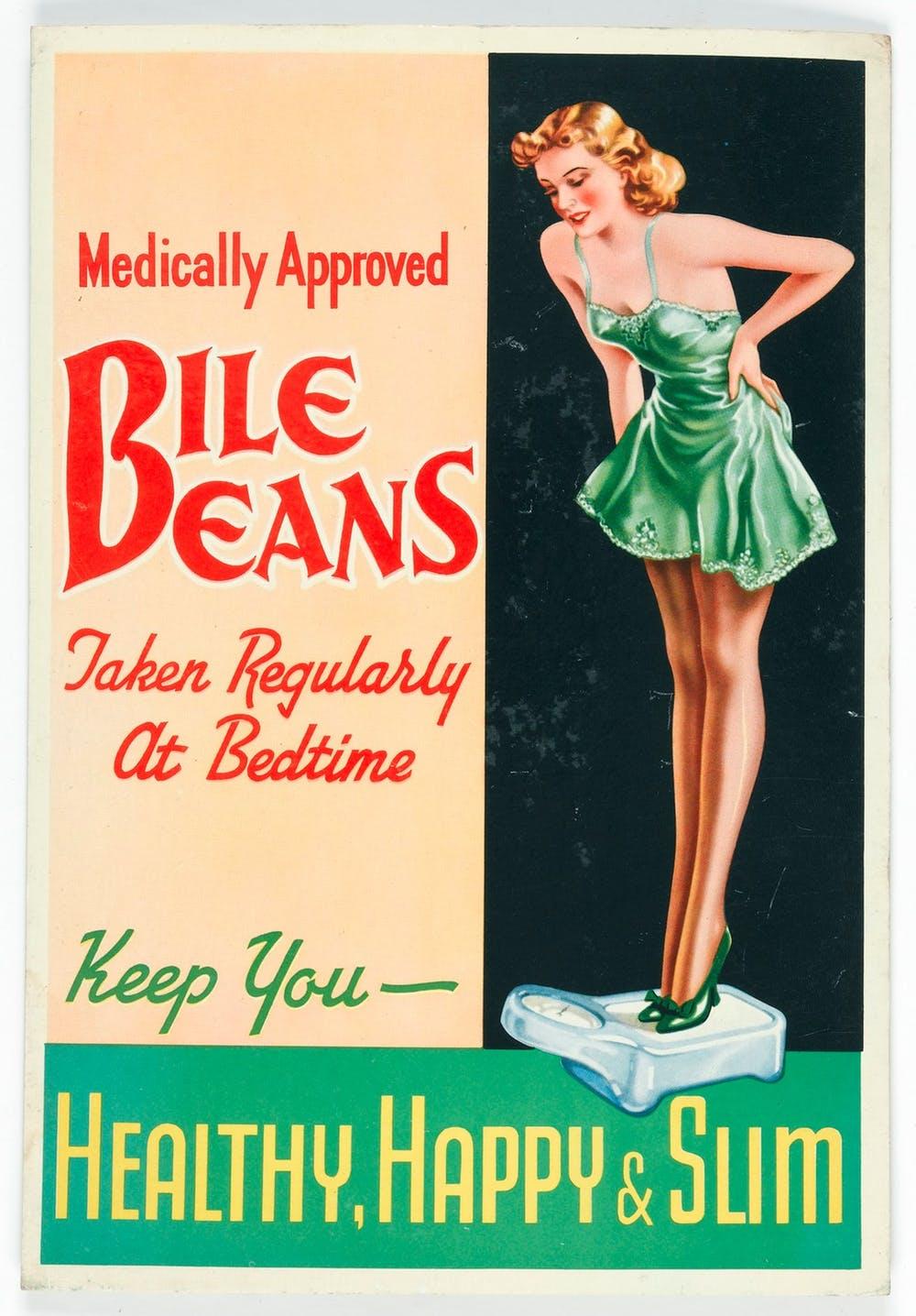

But while many of these products have specifically targeted millennials, the promotion of diet, detox, and laxative products has been around for centuries. Indeed, in the 19th and 20th centuries, laxative pill products like Beecham’s Pills and Bile Beans enjoyed a particular vogue. They were available over the counter and contained ingredients like ginger, pure soap powder, and aniseed. Although they were primarily laxatives, they also claimed to improve the complexion, boost spirits, and purify the blood.

Despite being controversial, these products were enormously popular. In the House of Lords in 1938, Lord Horder – a leading physician at the time – stated that the public were spending between £25-30m on these products every year. And consumers probably didn’t know exactly what they were ingesting, because many medicine manufacturers were not legally required to list the ingredients of their products on packaging before 1941.

Trust in advertising

Similar to the way modern diet pills and teas are advertised, testimonial advertising made 19th and 20th century over-the-counter medicine brands appear more personal, trustworthy, and authoritative – with recommendations from non-experts featuring regularly.

There was much debate at the time about whether 19th and 20th century testimonials were authentic. And while testimonials were probably based on genuine correspondence from consumers, they still could have been edited.

Today, it is similarly difficult to tell whether an influencer’s recommendation is genuine. Yet a recent study found that trust in “digital creators” is higher than trust in brands. The study found roughly 37 per cent of people age 18-34 were more likely to trust brands after they had seen sponsored posts from influencers. This trust often leads to a purchase: 42 per cent of those exposed to sponsored influencer content reported trying the recommended product or service, while 26 per cent made a purchase.

Advertising via influencers has transformed modern advertising and marketing. It has created a new league of authoritative “experts” that front brands and make them appear more trustworthy, personable, and familiar. This is key to the promotion of health and medicinal products that can positively and negatively affect the body.

Misleading consumers?

British influencers were criticised in the study for not disclosing when posts on Instagram include sponsored content. This caused concern about influencers misleading consumers, as recommendations can seem genuine when they are, in fact, financially motivated.

As a result, influencers have increasingly come under fire from the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) in Britain. The ASA and the Competition and Markets Authority launched an “Influencer’s Guide” in September 2018 to ensure influencers make their followers aware of sponsored content.

But even when influencers do disclose paid advertisements with “#ad” they can still be investigated by the ASA. In 2017, Sophie Kasaei, a reality star with over 2 million followers on Instagram, uploaded a picture with “Flat Tummy Tea” online. The ASA upheld a complaint against her due to a lack of scientific evidence for the claims made. Plus, the name “Flat Tummy Tea” did not comply with the EU’s register of nutrition and health claims.

Debunking ‘nonsense’

The ASA’s concerns demonstrate that modern brands have developed new and increasingly sophisticated ways of overcoming the absence of face-to-face interaction with consumers. And this trust that people invest in social media influencers has led to podcasts, editorial content, and documentaries that aim to “debunk” health trends, products, and diets. BBC podcasts such as All Hail Kale investigate “what foods, therapies and lifestyles to embrace – and which are just nonsense”.

Debunking such “nonsense” has similar parallels with the approach taken by the British Medical Association (BMA) towards over-the-counter medicines in the early 20th century. In 1909 and 1912, the BMA set out to “expose” these products by testing their ingredients. They aimed to educate the public, but their approach also cast the public as weak and irrational – ripe for being exploited by “quackery”.

In the same way, podcasts and articles debunk such health claims as “nonsense”, reminiscent of the use of the word “quackery”. But using dismissive language like this fails to understand why these products, treatments and lifestyles are so popular.

Restricting the advertising of these products on Instagram will not stop people from buying them. Long after the BMA tried to tackle the sale of over-the-counter medicines in Britain in the early 20th century, the public continued to buy them. And in being dismissive of these products and those that use them, there is a failure to understand why people consume them in the first place. Instead, more needs to be done to try to understand the complex structures, beliefs, habits, and traditions that motivate consumption of such products in the first place.

Erin Elizabeth Bramwell is a PhD candidate in history at Lancaster University. This article first appeared on The Conversation

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments