Scientists on brink of curing genetic heart disease in ‘defining moment’ for medicine

‘Once-in-generation opportunity to relieve families of the constant worry of sudden death’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Scientists believe they are just a few years away from a groundbreaking cure for genetic heart conditions that put 260,000 people in the UK at risk of sudden death each year.

Researchers have been awarded £30m to develop a cure for inherited heart muscle diseases that can kill young people “in the prime of their lives”.

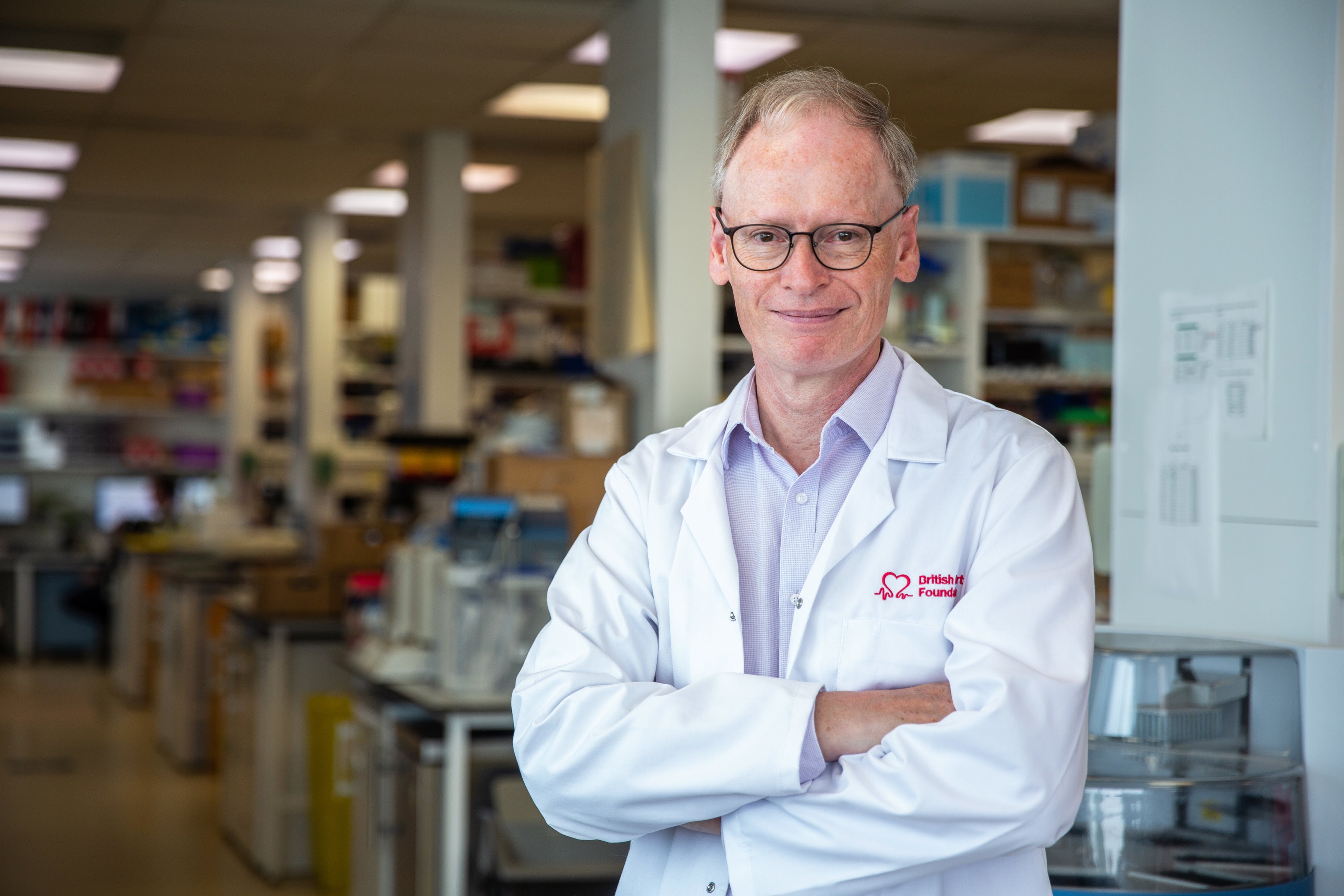

One of the leads for the Cure Heart project, Professor Hugh Watkins said the research was a “once-in-a-generation opportunity to relieve families of the constant worry of sudden death, heart failure and the potential need for a heart transplant”.

Professor Sir Nilesh Samani, medical director at the British Heart Foundation (BHF), said: “This is a defining moment for cardiovascular medicine ... [that] could also usher in a new era of precision cardiology.”

Using the BHF funding, the researchers aim to develop the first-ever cures for inherited heart muscle diseases by rewriting DNA with the aim of editing or silencing faulty genes.

The team, made up of scientists from the UK, US and Singapore, has so far proven its approaches are successful in animals with cardiomyopathies and in human cells.

The aim is for the therapies to be injected into the arm and stop progression or potentially cure those living with genetic cardiomyopathies.

The technology could also be used to prevent the disease from developing in family members who carry a faulty gene.

‘Life changing’

One patient with a heart condition said the cure would be “life changing”.

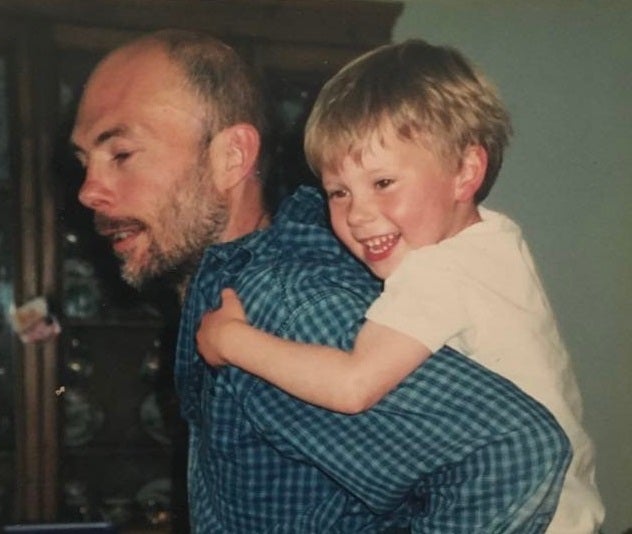

Max Jarmey, 27, was diagnosed with arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy in his teens, just a few years after his father Chris died suddenly.

He was forced to give up sport after his diagnosis.

Mr Jarmey said: “I’m pretty mentally robust but the first six months following my diagnosis were incredibly difficult. It was horrible to be told I had a condition like ARVC at the age I was told, and then to be forced to quit something I loved.”

He now lives with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD), a device which shocks his heart back to normal rhythm, protecting him from cardiac arrest.

He said: “When I think about my future, the decision to have children and their future, Cure Heart could make that decision easier. My children might never have to suffer like I have with this condition. That is completely life-changing.”

‘Once in a generation’

Each week in the UK, 12 people under the age of 35 die of undiagnosed heart conditions, often caused by an inherited heart muscle disease called genetic cardiomyopathy.

Around half of all heart transplants are needed because of cardiomyopathy and it is estimated around 260,000 people in the UK are impacted by these diseases.

Professor Hugh Watkins, from the Radcliffe Department of Medicine at the University of Oxford and lead investigator of Cure Heart, said: “This is our once-in-a-generation opportunity to relieve families of the constant worry of sudden death, heart failure and potential need for a heart transplant.

“After 30 years of research, we have discovered many of the genes and specific genetic faults responsible for different cardiomyopathies, and how they work. We believe that we will have a gene therapy ready to start testing in clinical trials in the next five years.”

Dr Christine Seidman at Harvard University and co-lead of Cure Heart, said: “Acting on our mission will be a truly global effort.

“We’ve brought in pioneers in new, ultra-precise gene editing, and experts with the techniques to ensure we get our genetic tools straight into the heart safely. It’s because of our world-leading team from three different continents that our initial dream should become reality.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments