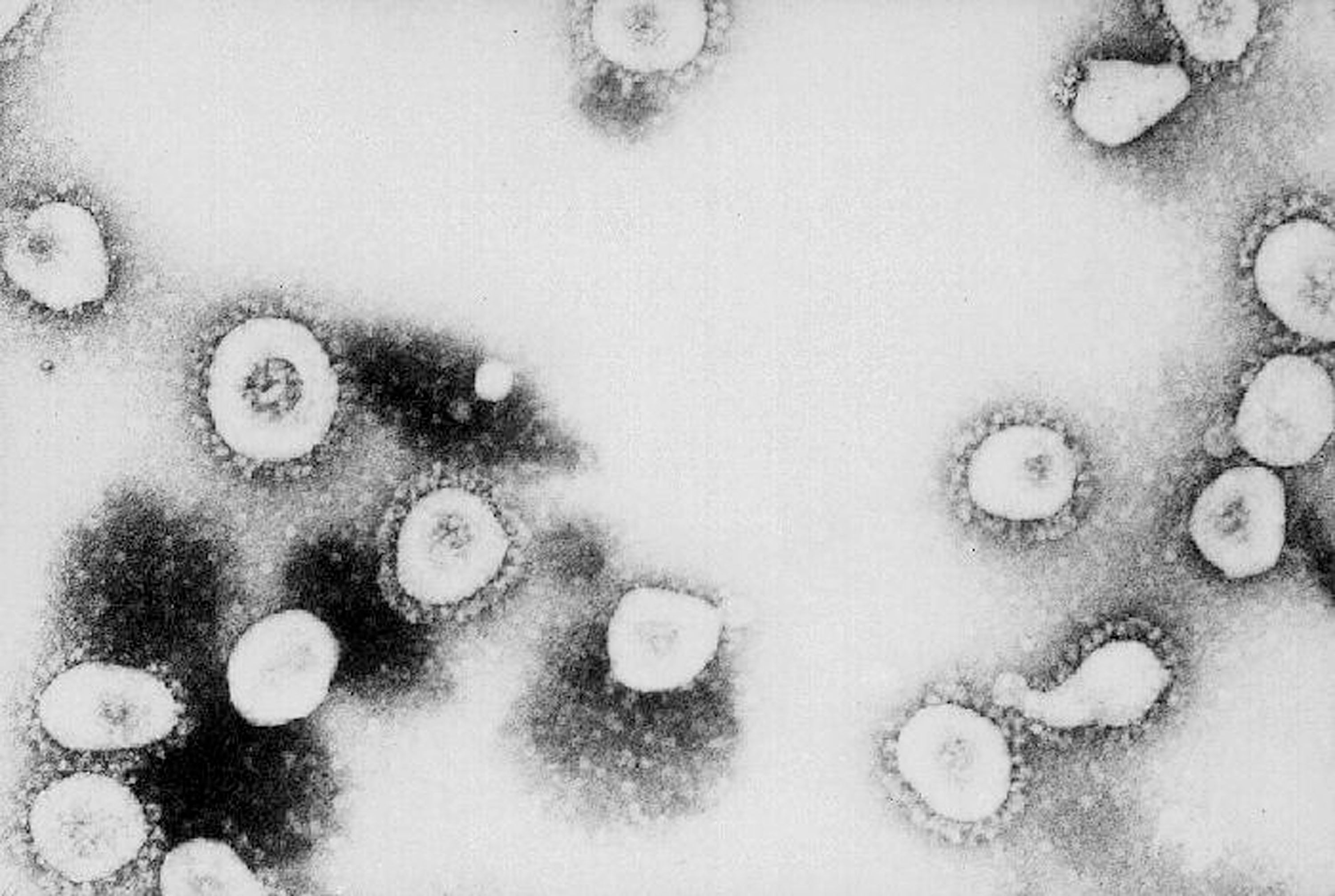

New coronavirus variants may have roots in immunocompromised patients, leading scientist says

People with weaker immune systems could be ‘part of the story’, says Professor Sharon Peacock, executive director of Covid-19 Genomics UK consortium

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The new variants of coronavirus that are being detected around the world may have their roots in immunocompromised patients, a leading UK scientist has said.

Professor Sharon Peacock, executive director of the Covid-19 Genomics UK consortium, said that people with weaker immune systems, which make them more vulnerable to falling severely ill, could be “part of the story” behind the various genetic mutations that have occurred in Sars-CoV-2.

The UK variant, called B.1.1.7, has been shown to be at least 50 per cent more transmissible than the original coronavirus, while fears have also been raised over the South African variant, which is believed to be capable of evading parts of the body’s immune response.

Another lineage of the virus has also been detected in travellers from Brazil, with analysis continuing to determine its virulence and infectiousness – though current evidence suggests “there’s no reason to think immunisation is not going to work” against it, said Prof Peacock.

She explained that patients with an impaired immune system can harbour Sars-CoV-2 for long periods of time, allowing it to acquire multiple mutations – some of which serve to the pathogen’s advantage – before being passed on in its new form.

“One of the interesting hypotheses – and it is a hypothesis at the moment – is that some people who have an impaired immune system can actually have chronic infection with Covid-19 and have the virus in their body for some period of time,” she said during a webinar held on Thursday by the Royal Society of Medicine.

“What people have observed in case studies at the moment is that such patients can have viruses that have changed quite a lot during the course of their clinical disease.”

Although the emergence of new variants could be “associated with people who have an impaired immune system”, more research was needed before any firm conclusions are drawn, Prof Peacock said.

People with chronic infection differ from long Covid sufferers, who have cleared the virus from their bodies but still experience symptoms and fallout from the disease.

Typically, Sars-CoV-2 acquires one to two mutations per month, thereby further extending the different lineages and branches of the virus. Yet scientists have identified an unexpected 23 genetic changes to the coding of B.1.1.7, suggesting it may have gone through a lengthy bout of evolution in a chronically infected patient.

“We know this is rare, but it can happen,” Professor Maria Van Kerkhove, a World Health Organisation epidemiologist, said last month.

Stephen Goldstein, a virologist at the University of Utah, said the British variant displayed “too many mutations to have accumulated under normal evolutionary circumstances”.

According to Prof Peacock, public health authorities in the UK and elsewhere are examining the role of immunocompromised patients to see “if there's more likelihood that a variant would arise [in these people] that is of concern to others”.

She said it was “possible” that these individuals “could be part of the story”.

Another hypothesis for the origin of the British variant is that it was brought to southeast England in September of last year, Prof Peacock added.

“What we know is that the UK is doing a lot of sequencing compared to other countries,” she said. “We've generated around half of all genomes in the global open access database.

“So, many countries wouldn’t know they had this particular variant. It could have been imported and then spread from there [in Kent]. That's one possibility.”

Prof Peacock said that the screening of waste water could also provide authorities with another tool for establishing the origins of new variants.

“Studying sewage is actually a really important capability, particularly as when people are asymptomatic,” she said.

“The other thing scientists are doing at the moment is looking to see if you can sequence fragments of the RNA of the virus, and whether you can understand the genetic code of the fragments of that virus in water.

“Through those fragments you can see whether you have particular lineages or particular variants, so that work is still under way.”

The Covid-19 Genomics UK consortium, one of the world’s largest coronavirus sequencing projects, has tracked the evolution of the pathogen since the start of the crisis, and detected the new UK variant last September.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments